Cabbage

brassica, mustard, plant, turnip, leaves, family, flowers and cattle

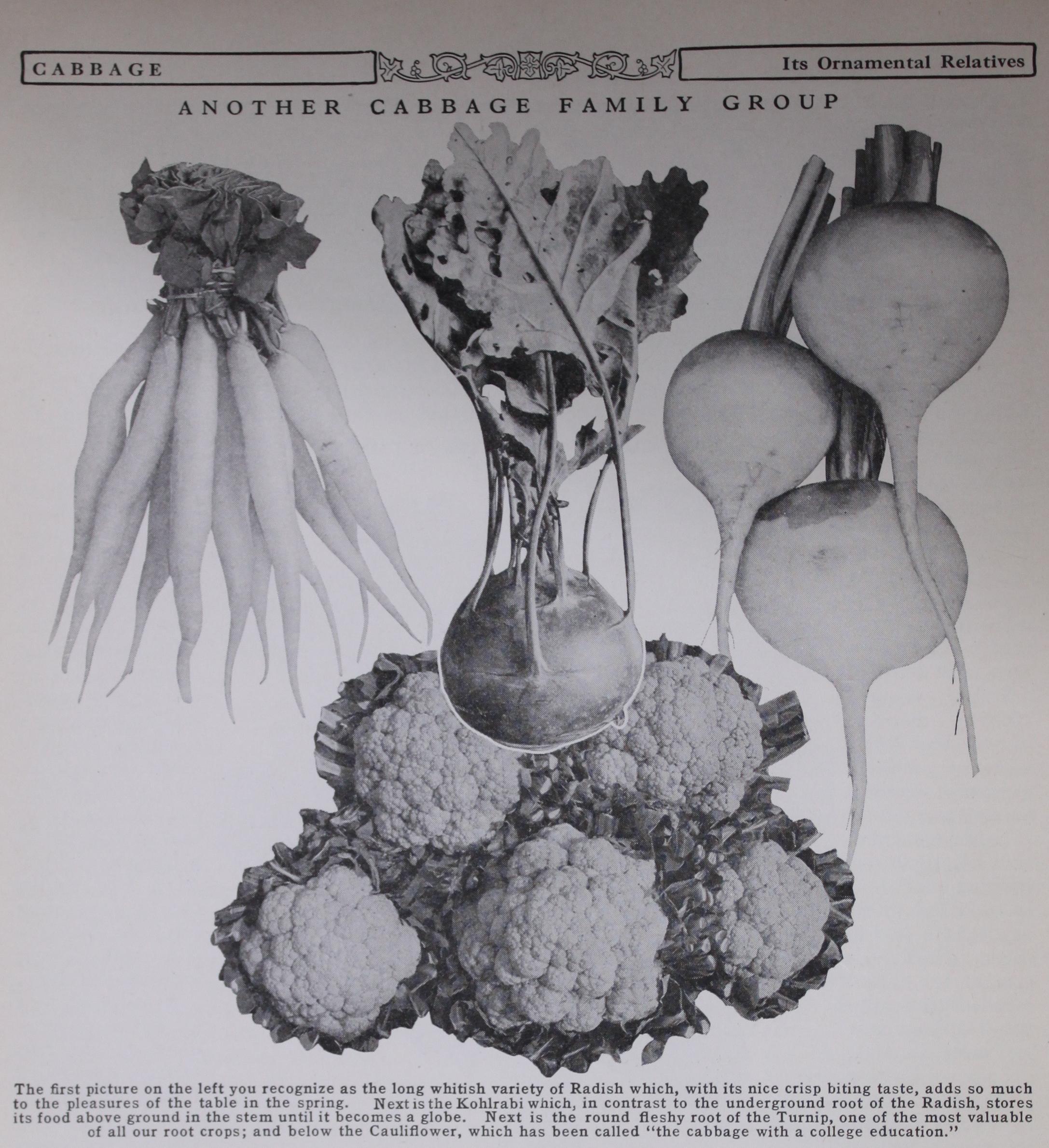

CABBAGE. Cauliflower and kale, Brussels sprouts and kohlrabi, cabbages and turnips, radishes, mus tards, and watercress—what a big and useful family of plants we have in the cabbage and its numerous relatives! Cauliflower, some one has said, is " a cabbage with a col lege education"; that is, it is a cab bage plant which has been carefully culti vated for centuries until it developed a very tight head of delicately flavored "flowers," delicious to eat either boiled or pickled. Kale is a member of the same family which runs to foliage instead of flowers, producing crinkled succulent leaves, which we eat as greens or feed to cattle. In Brussels sprouts (so named because it was culti vated long ago near Brussels, in Bel gium) we have a plant that bears a number of delicate leaf-buds an inch or so in diameter along the length of its tall thick stalk. Kohlrabi, on the other hand, is a variety that took to storing up nourishment in its thickened stem, until the stem became a turnip-like globe that sits on top of the ground, and makes very good food for both human beings and cattle. Another extraordinary member of the family put its vigor into the stem by shooting as tall as possible, in stead of swelling out like the kohlrabi. This is the Jersey cabbage or tree cabbage, that grows eight or ten feet high in the Channel Islands, and has a stout stem that is used for walking sticks and rafters in cottages; its leaves do not close into heads but are used as fodder for cattle.

In the cabbage proper we have a descendant of the wild cabbage that puts its strength only into the terminal leaf- bud, which forms the swollen compact head we so often eat raw, boiled, or pick led with salt in the form of sauerkraut.

Cultivation has de veloped more than 100 types of cabbage — smooth-leaved and wrinkle-leaved (also called Savoy); green and red; with heads conical, ob long, round, or flat.

Scientists tell us that cabbages yield a greater weight of green food to the acre than any other plant, and that there is no better fodder for cattle and sheep.

You can tell that all these descen dants of the wild cabbage are related to the mustard plant, both by the resem blance of the flowers and by the biting mustard-like flavor that their stems have to a greater or less degree.

The young mustard plants are sometimes eaten as salad, but they are chiefly culti vated for their white or black seeds, which are ground to make our familiar powdered mustard. Radishes also are near cousins of the mustard, with the hot biting taste usu ally well developed.

Their globular or elongated roots are delicious as relishes or in salads, and in Europe the young leaves and the seed pods are also eaten. Watercress and other kinds of cress,

which are among our Donular salad rnntprin1Q nicn betray their membership in the mustard family by their flavor. The horseradish, with its tear bringing taste, is a coarser relative of the radish and the watercress. Its white fibrous root is grated and steeped in vinegar with salt and sugar to make the condiment often eaten with meats; it is often mixed with grated turnip root to make it milder.

The same mustardy taste is conspicuous in the turnip before it is boiled. The turnip is one of our most valuable root crops for both human and animal food, even though it is nine-tenths water. The tender tops of early spring turnips are also good boiled as greens.

Several varieties have been developed, distinguished by their color, size, and shape. The rutabaga or Swedish' turnip is the large yellow variety grown in northern latitudes. The garden varieties grown for human food are generally smaller, tenderer, and more delicately flavored than the field turnips, grown chiefly for cattle feed, which sometimes attain a size of 20 to 25 pounds.

The botanical name of the large family which includes the foregoing useful plants is Brassicaceae (also called Cruci ferae). This group also embraces various ornamental flowers, such as the wallflower, rocket candytuft, sweet alyssum, and the curious rose-of-Jericho or resurrection plant. The resurrection plant, which grows in the desert regions about the Red Sea, has the strange property of curving its branches into a ball about the seed-pods after the leaves fall, ready to be blown hither and thither by the wind. When it reaches a moist place the branches expand and the pods open and release the seeds.

There are about 215 genera and 2,000 species of the Brassicaceae dispersed throughout the temperate regions.

Some are annuals, some perennials, but all have the charac teristic pungent watery juice. The flowers have 4 usually deciduous sepals and the 4 regular petals are hypogynous (that is, growing from the axis beneath the ovary or pistil) and are arranged so as to suggest the form of a cross (hence the name Cruciferae, meaning cross-bearers). Two of the 6 stamens are shorter than the others and have a lower insertion. The seeds are without albumen ; leaves alternate and without stipules; fruit a 2-celled pod. Scientific name of cabbage, Brassica oleracea; of cauliflower, Brassica oleracea botrytis; of Brussels sprouts, Brassica oleracea, var. bullata gemmifera; of radish, Baphanus sativus; of turnip, Brassica campestris and Brassica raga; of white mustard, Brassica alba; of black mustard, Brassica nigra; of garden cress, Lepidium sativum.