Calculating Machines

machine, disk, add, tens, moves and duodecillion

CALCULATING MACHINES. These wonderful little machines add, subtract, multiply, divide, and per form other mathematical operations that make them indispensable aids in banks, post-offices, insurance offices, government bureaus of statistics, large busi ness houses—wherever figures are constantly dealt with on a large scale. There are machines for every need, from the tiny reckoner for the retail merchant who deals only with figures of five digits or less, to the amazing "duodecillion" machine, which will give results up to 40 digits. To get an idea of the pro digious size of a duodecillion, suppose you had an in come of $1,000,000 a second. Before this amounted to a duodecillion dollars, 352,331,022,041,828.731,333, 333,333 years would elapse.

Besides these machines, there are other that per form the most intricate mathematical calculations involving logarithms and geometry. One of these, called the "tide predictor," will deliver in about two hours a tracing showing the movements of the tide at a given port for a year in advance. One of the most remarkable machines ever built is the electric tabulator used by the United States Census Bureau, which adds and records simultaneously statistics under 240 classifications (see Census).

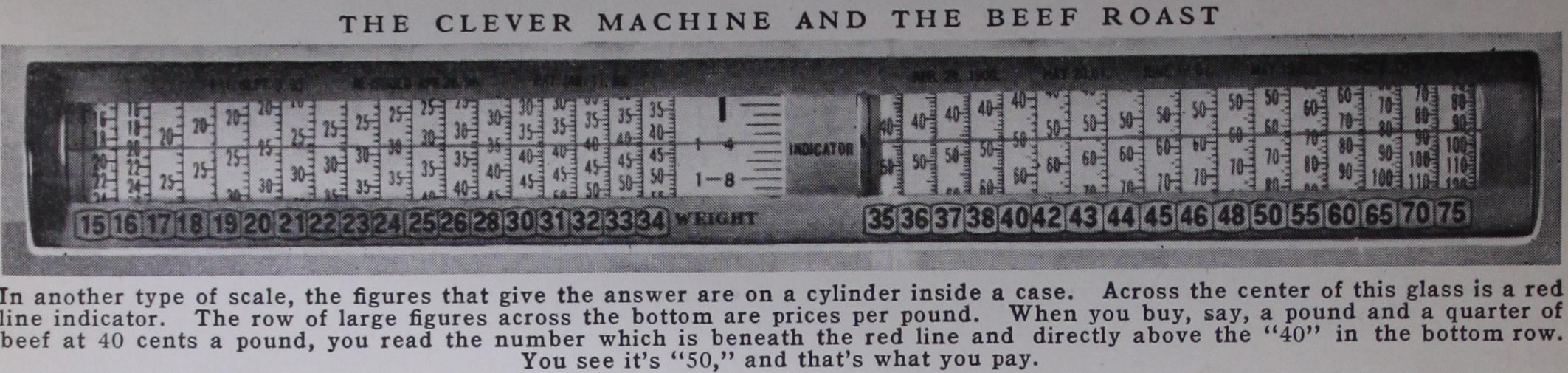

rows of ridges, but the principle is the same. So elabo rate are some of the electrically operated machines that they perform all the operations of bookkeeping and automatically post ledgers and statements.

The simplest type of adding machine is that used in the street-car fare register and in the automobile speedometer. It is essentially a series of disks each bearing around the edge the numbers from 0 to 9.

The disk at the right turns one step at each count.

When this has taken ten steps, or made a complete revolution, the next disk moves up one count, thus registering the "tens." In the same way when the "tens" disk has made a complete revolution, the third disk moves up one count, thus registering the "hundreds." The ordinary add ing machine works in precisely the same way, except that instead of adding only one unit at a time, it can add any desired number, by means of a complicated system of interlocking wheels.

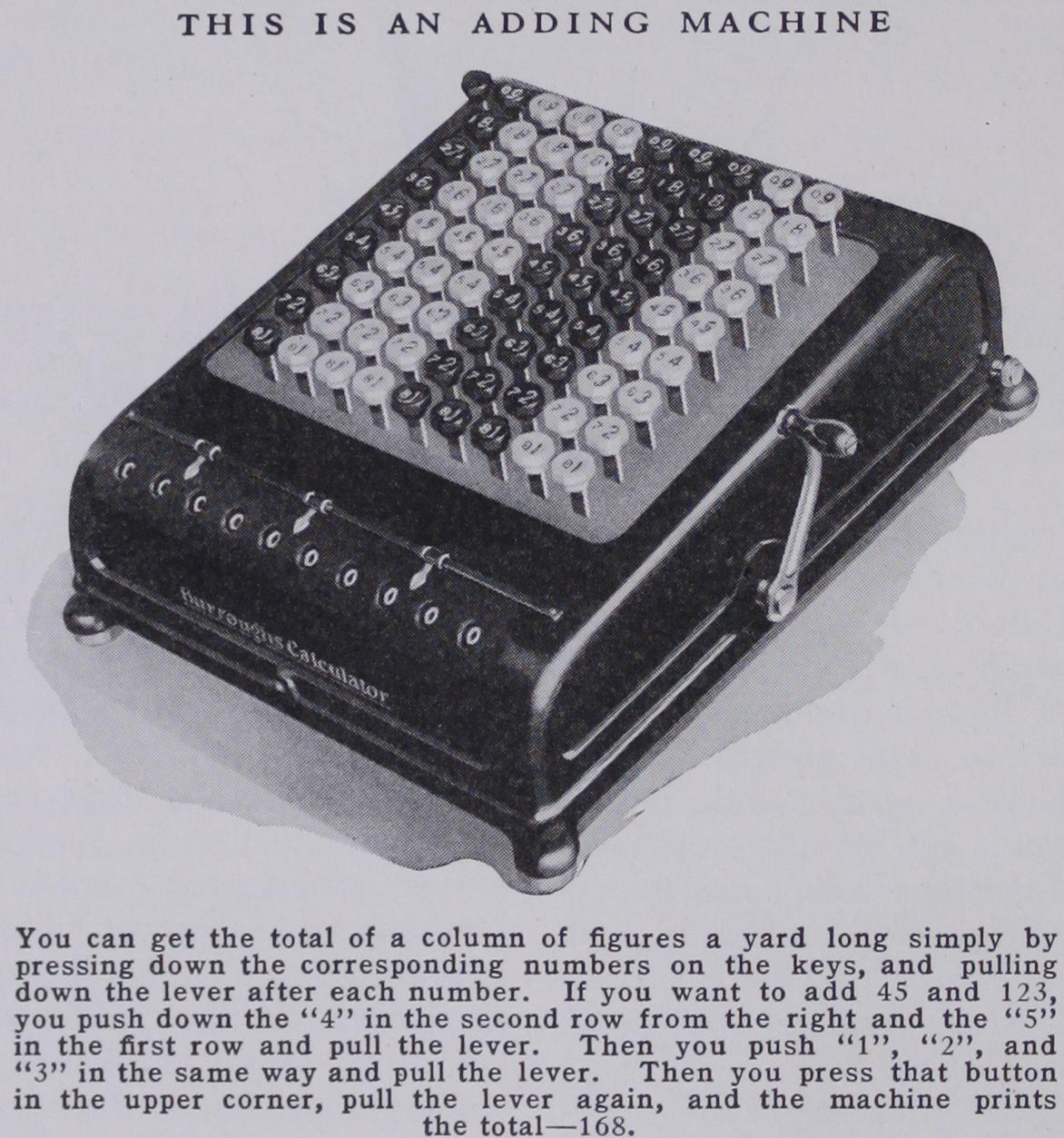

Each disk is controlled by a separate row of keys. To add 222 to 111, the "1" key is pressed down in each column. A turn of a lever causes each disk to move to the " 1" position. Then the "2" keys are pressed down in each column, the lever is pulled, and each disk moves two more steps, thus giving the result, 333.

To multiply with this machine, it is necessary to treat multiplication as successive additions. For example, to multiply 8 by 4, one would have to add 8 to itself three times. Ingenious mechanism has been contrived whereby this is done by a single pull of the lever. Division is similarly performed as successive subtractions.

Instead of disks some machines use cylinders with The father of the calculating machine was Blaise Pascal, a wonderful French mathematician and phi losopher, who in 1641, when he was 19 years old, produced the first machine that would carry tens.

No great improvements were made until 1820, when C. X. Thomas, an Englishman, brought out a machine which he called the" arithmometer." In 1822 another Englishman, Charles Babbage, conceived the idea of a great cal culating machine to perform the extended algebraic computa tions needed in astronomy an d navi gation. He spent more than $100,000 on this, but it was still unfinished at his death in 1871.

The man who did the most to make the calculating machine a practical commer cial success was an American, William S.

Burroughs. When his health broke down, in 1883, under the strain of bookkeeping i n a bank, Burroughs set about making a machine which would make much of this drudgery unnecessary.

For eight years he experimented ceaselessly and finally, in 1891, he produced a machine which is in essentials unchanged today. So this tired bank clerk revolutionized the world's bookkeeping. (See also Cash Register.)