Wung Foos Busy Day and His Land of Queer People

foo, little, fish, boys, china and school

When Wung Foo went to bed in the men's room he pulled a down quilt over his head. He was only a little boy, after all, and in the dark the goblin stories scared him. In the morning he was awakened by a thousand noises. Watchmen told the hour on bamboo drums. Beggars beat on the gate with sticks until a servant went out with rice. Peddlers cried out that they had fish and ducks and eggs and fruits and fat puppies to sell. A procession banged and rattled and squealed Chinese music. Wung Foo thought it was very sweet music. China had always had it and China changed very little in those days. He thought the old ways of doing things the very best ways in the world.

One very old way of doing things in China was for little boys to go to school before breakfast, and to go nearly every day in the year. The chief vaca tions were at New Year's in February, on kite flying day in October, and at the Feast of the Lanterns. Then fire crackers popped and snapped and banged all day long, as they do on our Fourth of July.

When Wung Foo went to school there were a thousand interesting things in the crowded streets—traveling performers, acrobats, wonder work ers, peep-shows, and refreshment sellers. But Wung Foo walked gravely along. When he met his school mates he shook his own hands inside his sleeves to show that he was glad to see them. When they got to the school the boys took their places on stools, with higher stools in front for tables; and the teacher was very cross.

At ten o'clock Wung Foo came home for breakfast.

At four he came home for dinner. It was a very good dinner of bird's-nest soup, fish, duck eggs, chop-suey, rice, and preserved kumquats. Chop suey is made of bits of chicken, pork, chestnuts, mushrooms, celery, and crisp little bean sprouts, all cooked together in oil and dressed with spicy brown sauce, and it is very good indeed. Kumquats are little oranges about as big as plums. Sometimes he had chrysanthemum fritters, made of the flower petals, with pineapple sauce. Instead of a fork, he used chopsticks which he handled very skilfully.

Things Wung Foo Saw on a Journey Once Wung Foo went on a journey with his father.

He went on a boat up the river. The river was so wide there was room for sailboats in the middle, and for streets of house boats along the banks.

Women washed and cooked on the decks of the house-boats. Chil dren played there with little barrels tied to them.

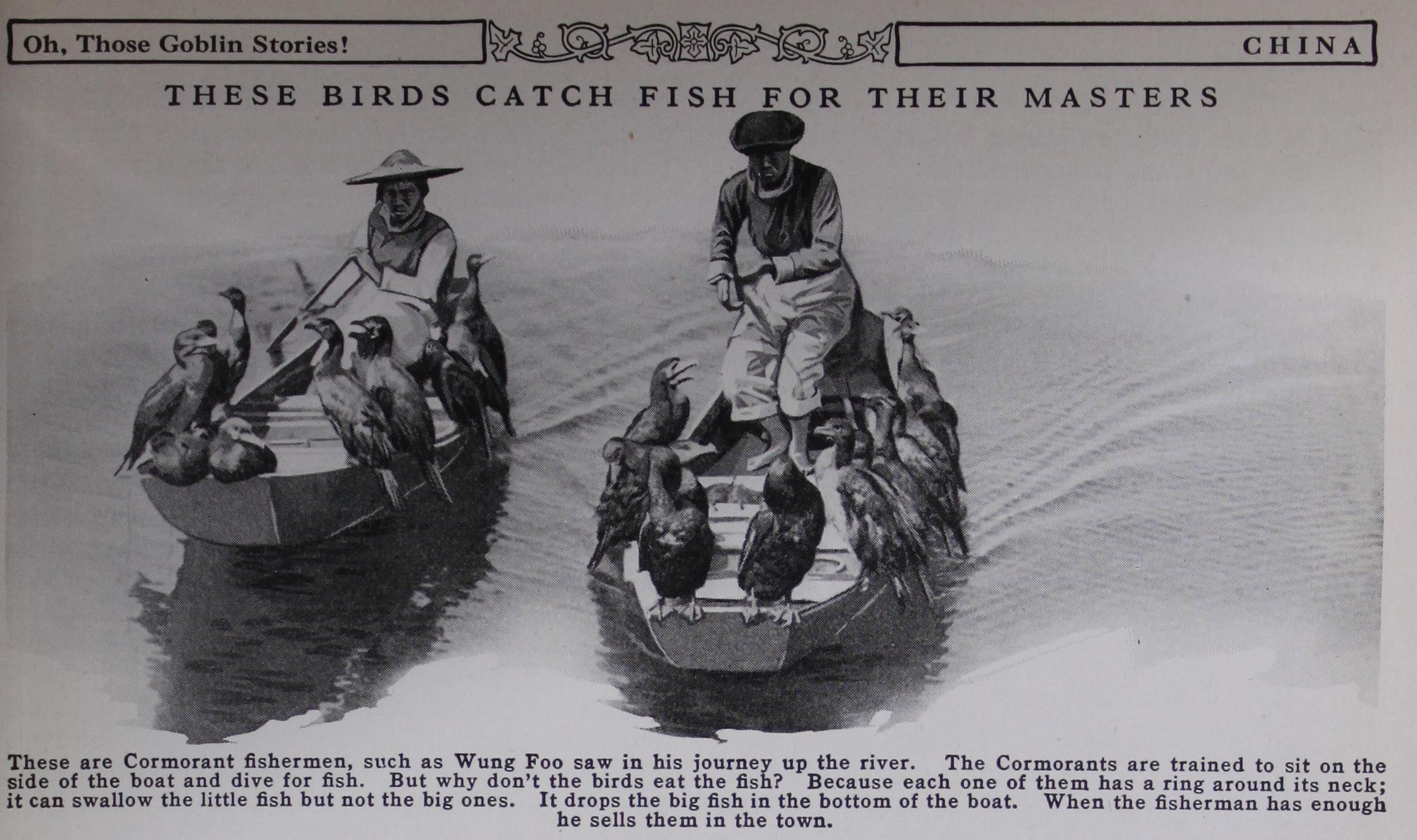

If they fell into the water the barrels kept them afloat until someone could pull them into the house again. The people who lived in house-boats were poor. Boys no older than himself tended ducks in marshes. Others fished with big birds called cor morants that were trained to dive and catch fish.

Then the boys would make the birds give up the fish. The little girls on the boats had big feet.

They would always have to work, and they could not have done this if their feet had been bound.

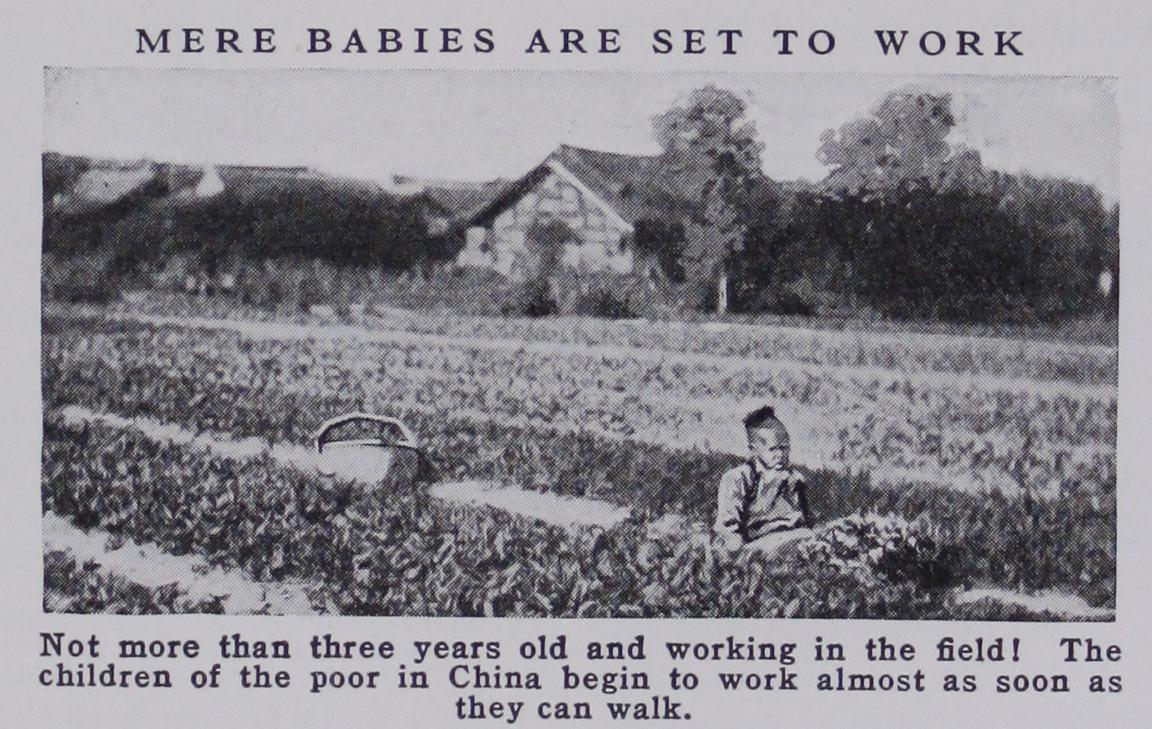

Wung Foo saw other little boys and girls picking cotton bolls, and tea leaves, and mulberry leaves to feed silk worms, and planting rice in wet ground.

He saw them bending over cotton and silk looms, and carrying heavy jars and tiles at the pottery works. They worked for a few cents a day. They lived in huts and ate nothing but rice and a very little fish, and drank the poorest tea.

When he went back home Wung Foo studied harder than ever. He was glad he was going to be a mandarin, or at least a silk merchant like his father.

Perhaps he might go away to be a merchant in Chinatown, in San Francisco, or to Manila, in the Philippine Islands. But when he got very rich he would go back to China, and when he died his bones would be buried with those of his forefathers accord ing to immemorial custom.