Boiler Accessories Calorimeters

steam and pipe

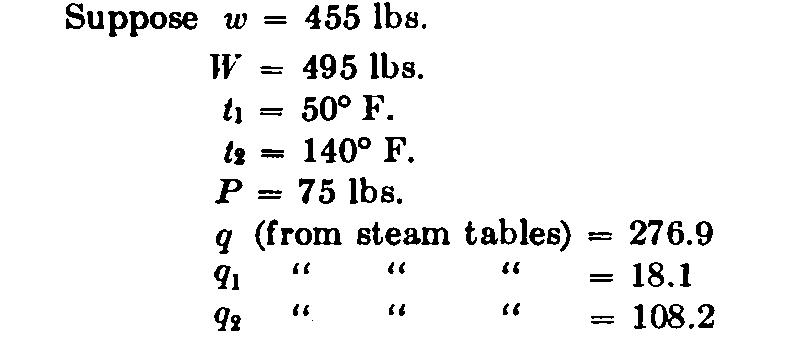

The solution of this equation will result in a formula which will save some mathematical computations. That the method may be perfectly clear, let us first consider a numerical example in full. Then the total heat in the barrel after condensation, is equal to (495 X 108.2) = 53,559 B. 1'. U. The total heat before condensation was equal to 455 X 18.1 = 8,235 B. T. U. Therefore the heat brought over by the moist steam will be 53,559 - 8,235 = 45,324 B. T. U. Now, from the steam tables q = 276.9; and r = 898.8. The heat given up by condensation of the dry steam will then be 898.8 X (495 - 455)x= 40x X 898.8 = 35,952x; and the heat of the liquid in the moisture and condensed steam will be 40 x 276.9 = 11,076, making the total heat in the moist steam = 11,076 + 35,952x. Therefore, 11,076 + 35,952x = 45,324 35,952x = 34,248 x = 0.952 That is, every pound of moist steam contains .952 lb. dry steam and .048 lb. moisture; or we may say there was 4.8 per cent of priming. The formula may be derived by the following algebraic work: Total heat in bbl. after condensation = W q2; Total heat in bbl. before condensation = w q1,; Total heat brought over by steam = TV q2, — w q1; Heat of liquid in condensed steam = (W - w) q; Latent heat in dry steam = x (W - w) r; Total heat in moist steam = x (W - w) r + (W -w) q. Therefore, x (W w) r + (W - w) q = W - w q1xr (W w) = TV q2- w A, - q + w q; or, transposing to a more convenient form, If r is the heat of vaporization, then r x (W- w) will equal the B. T. U. contained in the dry steam; and if q is the heat of the liquid corresponding to the same pressure, then q (1 - x) (W - w) will equal the B. T. U. contained in the moisture brought over by the steam. It is apparent that the sum of these two quantities will be the total number of B. T. U. brought from the steam main to the water barrel, and must be equal to q, W - q, w, the heat gained by the water in the The use of this form of apparatus is not especially to be commended, for it is liable to error, and a slight discrepancy in the weights or the temperatures may cause a large error in the result. In the above calculations, no allowance is made for loss of heat through radiation.

Separator Calorimeter. This instrument shown in Fig. 68, consists of a chamber A, into which is led a steam pipe D, bringing a sample of steam from the boiler or main. This pipe leads into an enlargement perforated with small holes, or into a chamber A as shown in Fig. 68. The calorimeter separates the moisture from the steam just as a steam separator does; and the exhaust, which is dry steam, passes out of the pipe P, wherein is inserted a diaphragm containing small ori-• flees, by means of which the quantity of steam flowing out can be calculated by thermodynamic methods. The exhaust steam can, of course, be led to some form of condensing apparatus, and the condensation weighed, if desired.

As the steam enters the calorimeter, the moisture is drawn toward the bottom of the chamber. The amount of water collected can readily be read from the gauge-glass at the side, to which a graduated scale should be attached.

The amount of moisture contained in the steam can be weighed directly by drawing it out of the gauge-cock E. The amount of dry steam is measured by its flow through the orifices, or by condensation.* If = weight of steam discharged from the calorimeter, and w = weight of water collected, then the percentage of priming will be w/(W+w) If only a small quantity of steam is used, an allowance must be made for condensation; but if the instrument is well lagged with hair felt or other suitable material, and a sufficient quantity of steam is used, the error from radiation may be neglected. Steam should be allowed to flow through the instrument until it has become thoroughly heated, before beginning the test.

Throttling Calorimeter. This was invented by Prof. Cecil H. Peabody, and is made with varying constructive detail s.

Fig. 69 shows the general arrangem e n t. The mixture of steam and water from the boiler is taken from the main steam pipe through what is termed a sampling pipe. Various forms of this pipe are made; one arrangement consists of a pipe closed at its inner end, but having numerous holes inch in diameter drilled staggering around the sides.

The calorimeter should be placed as close as possible to the main steam pipe; and the gauge' for indicating the pressure in the main steam pipe should be placed on the latter and near the calorimeter.

The gauge is sometimes connected to a tee on the pipe leading to the calorimeter; but it is better to have this gauge where the velocity of the flowing steam is less. A valve is placed in the pipe to the calorimeter, below which is inserted a nipple A having a small converging orifice D, about two-tenths of an inch in diameter and very carefully made. The object of such an orifice is to determine the weight of steam flowing through the calorimeter, so that an allowance can be made for the loss when testing an engine or boiler, where the net weight used is required. A cup B is screwed into the top, for holding an accurate thermometer. The cup is made of brass, and is filled with oil; but if mercury is used, the cup must be of iron or steel. A delicate gauge C, for determining the pressure in the calorimeter, and a pipe and valves at the bottom, complete the apparatus. The valve N is sometimes omitted, and a simple pipe used, as the throttling is best accomplished by use of the valve E or orifice D. All pipes leading to the calorimeter should be well covered with a good non-conductor.

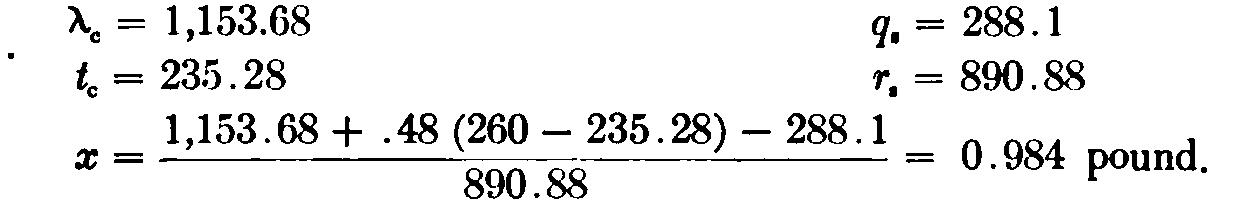

To use the instrument, proceed as follows: Open wide valves E and N, to bring the apparatus to a uniform temperature; then gradually close E until the steam in the calorimeter is superheated; that is, until the temperature as shown by the thermometer is greater than that corresponding to the absolute pressure determined from the reading of the gauge C and barometric pressure. The result may now be calculated as follows: x = Weight of steam contained in one pound of the mixture from the main steam pipe or other source; = Total heat corresponding to the absolute pressure determined from the reading of the gauge C and barometric pressure; T = Temperature as shown by the thermometer; = Temperature of steam corresponding to the absolute pressure as determined by the reading of the gauge C and barometric pressure; q, = Heat of the liquid corresponding to the absolute pressure in the steam pipe; r, = Heat of evaporation corresponding to the absolute pressure in the steam pipe; 0.48 = Heat required to superheat the steam one degree Fahrenheit under constant pressure.

Total heat in 1 lb. superheated steam in calorimeter = lambda(c)+ 0.48 (T — B. T. U.

Total heat in 1 lb. moist steam in steam main = xr, + q, B. T. U. These two quantities are equal; and x, being the only unknown quantity, the equation can easily be solved.

Example. Barometric pressure, 14.78 lbs. Absolute pressure in main steam pipe, 87.78 lbs. Absolute pressure in calorimeter, 23.03 lbs. Temperature (T) = 260° F. Then, Or, in other words, 98..4 per cent of the mixture is steam; or the moisture = 1 — 0.984 = 0.016, or 1.6 per cent.

This form of calorimeter is suitable only for cases where the moisture does not exceed three per cent of the mixture. Its principle is based upon the assumption that there is no loss of heat, in which case steam mixed with a small amount of water is superheated when the pressure is reduced by throttling.