Boiler Accessories Feed Apparatus

water and steam

In stationary practice, it is quite common to admit the feed-water into the steam space through a horizontal pipe entering it through the tube-plate a few inches below the low-water level, and terminating in a perforated pipe of large diameter. This method distributes the feedwater admirably, and allows it to become considerably heated before it reaches the bottom of the boiler. If the feed-water contains a considerable amount of magnesia or calcium carbonate, holes so arranged in the feed-pipe are likely to become clogged and the feed interrupted. Water. of this sort should be fed into a trough, or the feed-pipe be opened at the top by a long slot, so that the feed-water may overflow. The trough in this case forms an admirable mud-drum or sediment collector.

In internally-fired boilers of the "Cornish" or "Lancashire" type, the feed is usually delivered near the bottom through a horizontal pipe—either through the front end or by a vertical pipe through the crown. This method is not conducive to the best circulation.

In addition to these effects on circulation, there are other grave objections to introducing feed-water near the bottom of the boiler; for, should anything happen to the• feed-pump, or a piece of scale lodge under the check-valve, the water might be almost entirely blown out of the boiler before the difficulty could be discovered or remedied.

If the pipe enters in the vicinity of the low-water level, no water could be drawn out below this point.

The feed supply should always be regulated so as to keep the water-level as nearly stationary as possible; this is not only much more economical, but also far better for the boiler, than to wait for the water-level to fall and then feed a few inches rapidly. The sudden introduction of a large volume of comparatively cold feed-water, causes local contraction of the plates, and hence tends to cause leakage; moreover, it necessitates irregular firing if anything like a uniform steam pressure is to be maintained.

Sometimes the feed-water is forced into the steam space in the form of a fine spray. In this way it not only is thoroughly heated before mingling with the water in the boiler, but the air is got rid of; and salts, such as sulphate of lime, insoluble at high temperatures, arc immediately precipitated. But the advantage of introducing. the feed-water in a body so as to produce useful circulating currents, should not he overlooked.

If several boilers are attached together in the form of a battery, each should be supplied with an independent connection to feed pipe. Otherwise a damage to the feed-pipe in one boiler might affect

the others. Moreover, if several boilers are fed from one pipe, the pressure in each of them being slightly different, an excess of water will naturally be fed into the boiler having the least pressure, whereas it is usually the case that the most water is needed in the boiler having the greatest pressure. The automatic float previously referred to, can regulate the amount of water fed into boilers only in a general way, through providing a method by means of which all the condensation is fed back into some of the boilers; but the quantity of feed which is led into 'each individual boiler must be watched and regulated by the water tender, who can open or close the individual valves as desired.

Pumps. Boilers are usually fed by a small, direct-acting steam pump placed near the boiler. Although these pumps require a large steam supply per horse-power per hour, the total amount of steam used is small because the work done is small A more economical pump is the power pump driven by the large steam engine; hut in this case the rate at which water is supplied is not easily regulated to the demand of the boiler. Power pumps are usually arranged to pump a larger quantity of water into the boiler than is required, the excess of water being allowed to flow back into the suction pipe through a relief valve.

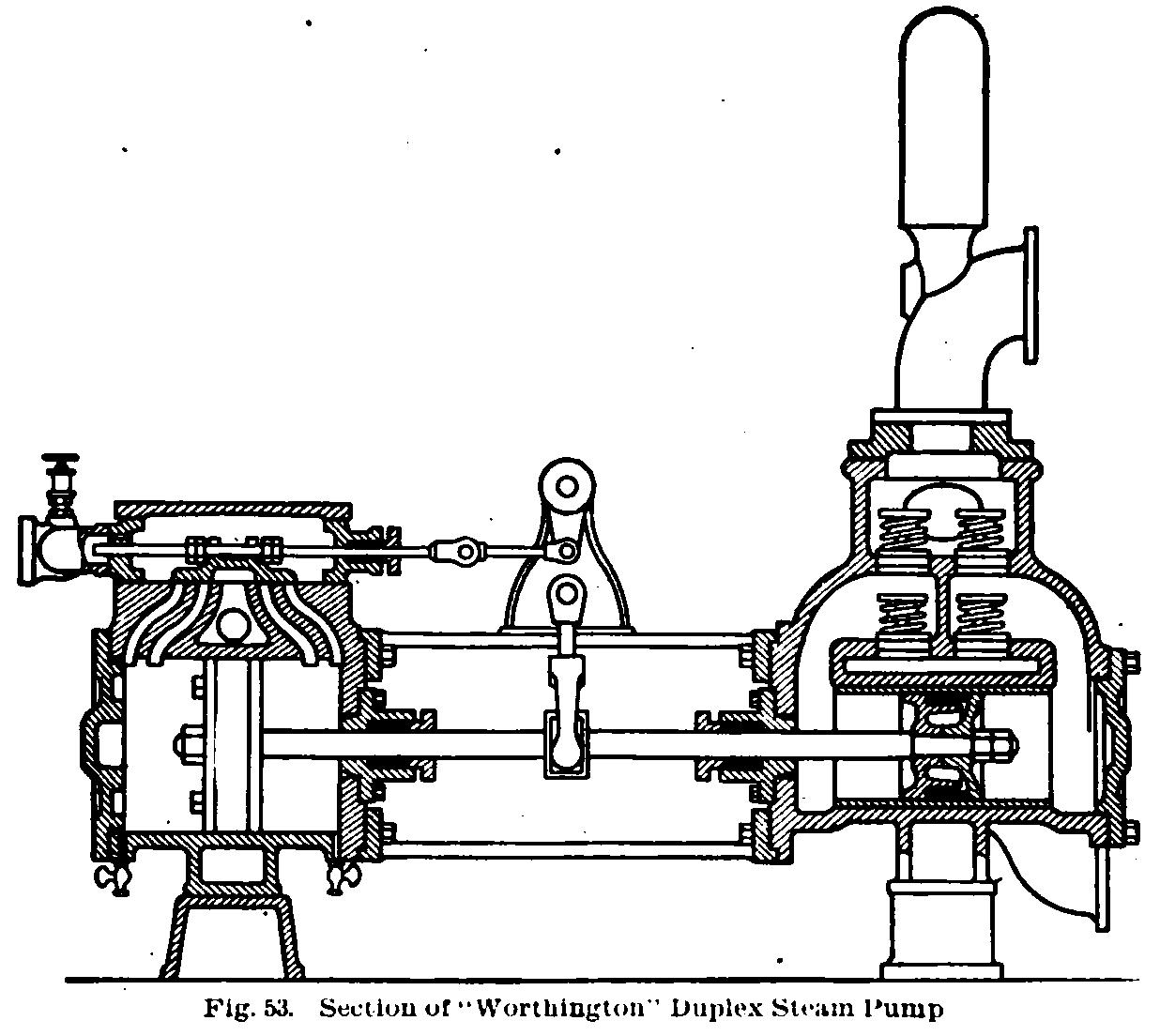

The pump shown in Fig. 52 is well adapted for feeding boilers. In Fig. 53 is shown the section of a duplex "Worthington" steam pump. The action of each of these two types is similar. Steam, controlled by valves, drives the piston in the steam cylinder, which moves the plunger in the water cylinder, since both are fastened to the same rod. The movement of the plunger forces a part of the water in front of it up through the valves into the air-chamber, and through the pipes into the boiler. On account of the partial vacuum caused by the Movement of the plunger, water will be drawn from the suction pipe, through the valves, into the pump 'cylinder, filling the space left by the movement of the plunger. During the return stroke, this water is forced up into the air-chamber, and a like quantity enters the other end of the pump cylinder. The valves are kept on the seats by light springs, until the pressure on the bottom side is sufficient to lift them and allow water to flow through.