Wage Rates and Family Income

WAGE RATES AND FAMILY INCOME The manipulation of individual prices is neither an efficient nor an equitable device for changing the distribution of personal income. This is a well-known dictum that has received much documentation in analyses of our agricultural programs. The relevance of the dictum to minimum wage legislation is easily demonstrated.

One cannot expect a close relationship between the level of hourly wage rates and the amount of family income. Yet family income and needs are the fundamental factors in the problem of poverty. The major sources of discrepancy may be catalogued.

First, the hourly rates are effective only for those who receive them, and it was shown in Section 1 that the least productive workers are forced into uncovered occupations or into unemployment.

Second, hourly earnings and annual earnings are not closely related. The seasonality of the industry, the extent of overtime, the amount of absenteeism, and the shift of workers among industries, are obvious examples of factors which reduce the correlation between hourly earnings and annual earnings.

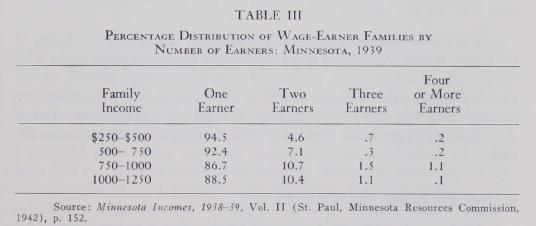

Third, family earnings are the sum of earnings of all workers in the family, and the dispersion of number of workers is considerable. The summary in Table III for low income wage-earner families in Minnesota in 1939, shows that in the $250-$500 income class one-twentieth of the families had more than one earner and in the higher income classes the fraction rose to one-eighth.

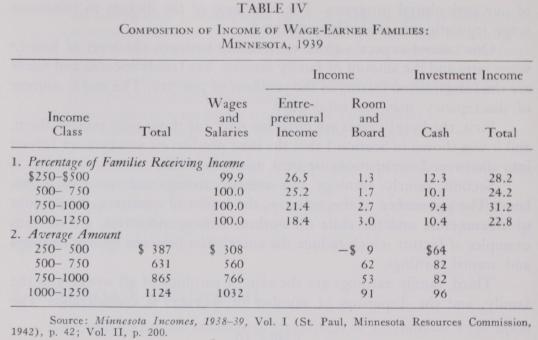

Fourth, although wages are, of course, the chief component of the income of low-wage families, they are by no means the only component. It is indicated in Table IV that a tenth of the wage-earner families had cash investment income, a quarter had entrepreneural income, and a quarter owned their homes.

All of these steps lead us only to family income; the leap must still be made to family needs. It is argued in the next section that family composition is the best criterion of need, and whether this be accepted or not, it is clearly an important criterion. The great variation in family size among wage-earner families is strongly emphasized by the illustrative data in Table V; an income adequate for one size is either too large or too small for at least half the families in that income class.

The connection between hourly wages and the standard of living of the family is thus remote and fuzzy. Unless the minimum wage varies with the amount of employment, number of earners, non-wage income, family size, and many other factors, it will be an inept device for combatting poverty even for those who succeed in retaining employment. And if the minimum wages varies with all of these factors, it will be an insane device.