Direct or Amitotic Division I

nucleus and attraction-sphere

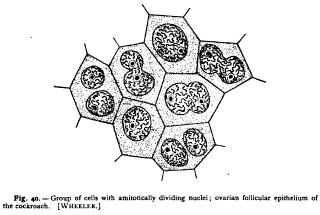

DIRECT OR AMITOTIC DIVISION I. General Sketch We turn now to the rarer and simpler mode of division known as amitosis ; but as Flemming has well said, it is a somewhat trying task to give an account of a subject of which the final outcome is so unsatisfactory as this; for in spite of extensive investigation, we still have no very definite conclusion in regard either to the mechanism of amitosis or its biological meaning. Amitosis, or direct division, differs in two essential respects from mitosis. First, the nucleus remains in the resting state (reticulum), and there is no formation of a spireme or of chromosomes. Second, division occurs without the formation of an amphiaster ; hence the centrosome is not concerned with the nuclear division, which takes place by a simple constriction. The nuclear substance, accordingly, undergoes a division of its total mass, but not of its individual elements or chromatingranules (Fig. 4o).

Before the discovery of mitosis, nuclear division was generally assumed to take place in accordance with Remak's scheme (p. 45). The rapid extension of our knowledge of mitotic division between the years 1875 and 1885 showed, however, that such a mode of division was, to say the least, of rare occurrence, and led to doubts as to whether it ever actually took place as a normal process. As soon, however, as attention was especially directed to the subject, many cases of amitotic division were accurately determined, though very few of them conformed precisely to Remak's scheme. One such case is that described by Carnoy in the follicle-cells of the egg in the mole-cricket, where division begins in the fission of the nucleolus, followed by that of the nucleus. Similar cases have been since described, by Hoyer ('9o) in the intestinal epithelium of the nematode Rhabdonema, by Korschelt in the intestine of the annelid Ophryotrocha, and in a few other cases. In many cases, however, no preliminary fission of the nucleolus occurs ; and Remak's scheme must, therefore, be regarded as one of the rarest forms of cell-division ( ! ).

2. Centrosome and Attraction-Sphere in Amitosis The behaviour of the centrosome in amitosis forms an interesting question on account of its bearing on the mechanics of cell-division. Flemming observed ('gt) that the nucleus of leucocytes might in some cases divide directly without the formation of an amphiaster, the attraction-sphere remaining undivided meanwhile. Heidenhain showed in the following year, however, that in some cases leucocytes containing two nuclei (doubtless formed by amitotic division) might also contain two asters connected by a spindle. Both Heidenhain and

Flemming drew from this the conclusion that direct division of the nucleus is in this case independent of the centrosome, but that the latter might be concerned in the division of the cell-body, though no such process was observed. A little later, however, Meves published remarkable observations that seem to indicate a functional activity of the attraction-sphere during amitotic nuclear division in the " spermatogonia" of the Krause and Flemming observed that in the autumn many of these cells show peculiarly-lobed and irregular nuclei (the " polymorphic nuclei" of Bellonci). These were, and still are by some writers, regarded as degenerating nuclei. Meves, however, asserts — and the accuracy of his observations is in the main vouched for by Flemming— that in the ensuing spring these nuclei become uniformly rounded, and may then divide amitotically. In the autumn the attraction-sphere is represented by a diffused and irregular granular mass, which more or less completely surrounds the nucleus. In the spring, as the nuclei become rounded, the granular substance draws together to form a definite rounded sphere, in which a distinct centrosome may sometimes be made out. Division takes place in the following extraordinary manner : The nucleus assumes a dumb-bell shape, while the attraction-sphere becomes drawn out into a band which surrounds the central part of the nucleus, and finally forms a closed ring, encircling the nucleus. After this the nucleus divides into two, while the ringshaped attraction-sphere (" archoplasm ") is again condensed into a sphere. The appearances suggest that the ring-shaped sphere actually compresses the nucleus, and cuts it through. In a later paper ('94), Meves shows that the diffused " archoplasm " of the autumn-stage arises by the breaking down of a definite spherical attraction-sphere, which is reformed again in the spring in the manner described, and in this condition the cells may divide either mitotically or amitotically. He adds the interesting observation, since confirmed by. Rawitz ('94), that in the spermatocytes of the salamander, the attraction-spheres of adjoining cells are often connected by intercellular bridges, but the meaning of this has not yet been determined.