The Mechanism of Mitosis

rays and van

THE MECHANISM OF MITOSIS We now pass to a consideration of the forces at work in mitotic division, which leads us into one of the most debatable fields of cytological inquiry.

1. Function of the Amthiaster All observers agree that the amphiaster is in some manner an expression of the forces by which cell-division is caused, and many accept, in one form or another, the view first clearly stated by that the asters represent in some manner centres of attractive forces focussed in the centrosome or dynamic centre of the cell. Regarding the nature of these forces, there is, however, so wide a divergence of opinion as to compel the admission that we have thus far accomplished little more than to clear the ground for a precise investigation of the subject ; and the mechanism of mitosis still lies before us as one of the most fascinating problems of cytology.

(a) The Theory of Fibrillar Contractility. — The view that has taken the strongest hold on recent research is the hypothesis of fibrillar contractility. First suggested by Klein in 1878, this hypothesis was independently put forward by Van Beneden in 1883, and fully outlined by him four years later in the following words : " In our opinion, all the internal movements that accompany cell-division have their immediate cause in the contractility of the protoplasmic fibrillae and their arrangement in a kind of radial muscular system, composed of antagonizing groups " (i.e. the asters with their rays). " In this system the central corpuscle (centrosome) plays the part of an organ of insertion. It is the first of all the various organs of the cells to divide, and its division leads to the grouping of the contractile elements in two systems, each having its own centre. The presence of these two systems brings about cell-division, and actively determines the paths of the secondary chromatic asters " (i.e. the daughter-groups of chromosomes) " in opposite directions. An important part of the phenomena of (karyo-) kinesis has its efficient cause, not in the nucleus, but in the protoplasmic body of the This beautiful hypothesis was based on very convincing evidence derived from the study of the Ascaris egg, and it was here that Van Beneden first demonstrated the fact, already suspected by Flemming, that the daughter-chromosomes move apart to the poles of the spindle, and give rise to the two respective daughter-nuclei.'

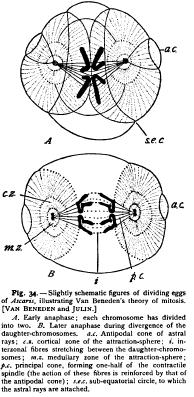

Van Beneden describes the astral rays, both in Ascaris and in tunicates, as differentiated into several groups (Fig. 34). One set, forming the " principal cone," are attached to the chromosomes and form one-half of the spindle, and, by the contractions of these fibres, the chromosomes are passively dragged apart. An opposite group, forming the " antipodal cone," extend from the centrosome to the cell-periphery, the base of the cone forming the " polar circle." These rays, opposing the action of the principal cones, not only hold the centrosomes in place, but, by their contractions, drag them apart, and thus cause an actual divergence of the centres. The remaining astral rays are attached to the cellperiphery and are limited by a sub-equatorial circle. Later observations indicate, however, that this arrangement of the astral rays is not of general occurrence, and that the rays often do not reach the periphery, but lose themselves in the general reticulum.

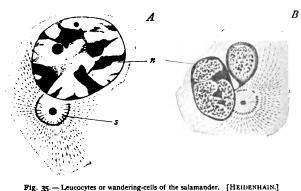

Van Beneden's general hypothesis was accepted in the following year by Boveri ('88, 2), who contributed many important additional facts in its support, though neither his observations nor those of later investigators have sustained Van Beneden's account of the grouping of the astral rays. Boveri showed in the clearest manner that, during the fertilization of Ascaris, the astral rays become attached to the chromosomes of the germ-nuclei ; that each comes into connection with rays from both the asters ; that the chromosomes, at first irregularly scattered in the egg, are drawn into a position of equilibrium in the equator of the spindle by the shortening of these rays (Figs. 65, 104); and that the rays thicken as they shorten. He showed that as the chromosome splits, each half is connected only with rays (spindlefibres) from the aster on its own side; and he followed, step by step, A. Cell with a single nucleus containing a very coarse network of chromatin and two nucleoli (plasmosomes) ; s. permanent aster, its centre occupied by a double centrosome surrounded by an attraction-sphere. B. Similar cell, with double nucleus; the smaller dark masses in the latter are oxychromatin-granules (linin), the larger masses are basichromatin (chromatin proper).