The Nucleus a

network and chromatin

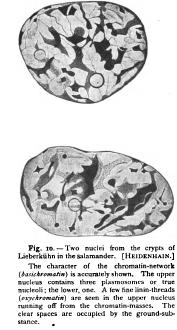

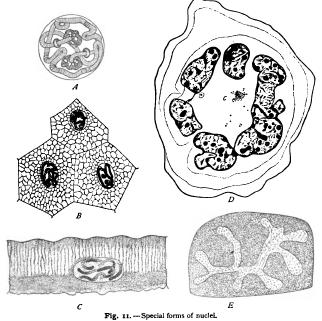

c. The nucleoli, one or more larger rounded or irregular bodies, suspended in the network, and staining intensely with many dyes ; they may be absent. The bodies known by this name are of at least two different kinds. The first of these, the so-called true nucleoli or p/asmosomes (Figs. 5, 7, B, 10), are of spherical form, and by treatment with differential stains such as hwmatoxylin and eosin are found to consist typically of a central mass staining like the cytoplasm, surrounded by a shell which stains like chromatin. Those of the other form, the " net-knots " (Netzknoten), or karyosomes, are either spherical or irregular in form, stain like the chromatin, and appear to be no more than thickened portions of the chromatic network (Figs. 5, 7, A, lo). Besides the nucleoli the nucleus may in exceptional cases contain the centrosome (p. 225), which has undoubtedly been confounded in some instances with a true nucleolus or There is strong evidence that the true nucleoli are 1 Flemming first called attention to the chemical difference between the true nucleoli and the chromatic reticulum ('82, pp. 138, 163) in animal cells, and Zacharias soon afterwards studied more closely the difference of staining-reaction in plant-cells, showing that the relatively passive bodies that represent accumulations of reservesubstance or by-products, and play no direct part in the nuclear activity (p. 93).

d. The ground-substance, nuclear sat, or karyolynith, a clear subA. Permanent spireme-nucleus, salivary gland of Chironomus larva. Chromatin in a single thread, composed of chromatin-discs (chromomeres), terminating at each end in a true nucleolus or plasmosome. [BALBIANI.] P. Permanent spireme-nuclei, intestinal epithelium of dipterous larva Ptycheptera. [VAN GF.HUCHTEN.] C. The same, side view.

D. Polymorphic ring-nucleus, giant-cell of bone-marrow of the rabbit ; c, a group of centrosomes or centrioles. [HEIDENHAiN.] E. Branching nucleus, spinning-gland of butterfly larva (Pieris). [KoRscHELT.] stance occupying the interspaces of the network and left unstained by many dyes which colour the chromatin intensely. Until recently former are especially coloured by alkaline carmine solutions, the latter by acid solutions. Still later studies by Zacharias, and especially by Heidenhain, show that the medullary substance (pyrenin) of true nuclei is coloured by acid anilines and other plasma stains, while the chromatin has a special affinity for basic anilines. Cf. p. 242.

the ground-substance has been regarded as a fluid or semi-fluid, but recent researches by Reinke and others have thrown doubt on this view, as described at p. 28.

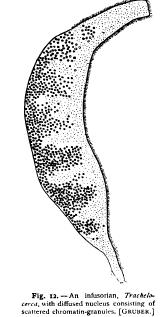

The configuration of the chromatic network varies greatly in different cases. It is sometimes of a very loose and open character, as in many epithelial cells (Fig. 1) ; sometimes extremely coarse and irregular, as in leucocytes (Fig. to) ; sometimes so compact as to appear nearly or quite homogeneous, as in the nuclei of spermatozoa and in many Protozoa. In some cases the chromatin does not form a network, appears in the form of a thread closely similar to the spiremestage of dividing nuclei (cf. p. 47). The most striking case of this kind occurs in the salivary glands of dipterous larvae (Chi ronomus), where, as described by Balbiani, the chromatin has the form of a single convoluted thread, composed of transverse discs and terminating at each end in a large nucleolus (Fig. 1 1, A). Somewhat similar nuclei (Fig. 1 1, B) occur in various glandular cells of other insects (Van Gehuchten, Gilson), and also in the young ovarian eggs of certain animals (cf. p. 193). In certain gland-cells of the marine isopod Anilocra it is arranged in regular rosettes (Vom Rath). Rabl, followed by Van

Gehuchten, Heidenhain, and others, has endeavoured to show that the nuclear network shows a distinct polarity, the nucleus having a " pole " towards which the principal chromatin-threads converge, and near which the centrosome lies.' In many nuclei, however, no trace of such polarity can be discerned.

The network may undergo great changes both in physical configuration and in staining capacity at different periods in the life of the same cell, and the actual amount of chromatin fluctuates, sometimes to an enormous extent. Embryonic cells are in general characterized by the large size of the nucleus; and Zacharias has shown in the case of plants that the nuclei of meristem and other embryonic tissues are not only relatively large, but contain a larger percentage of chromatin than in later stages. The relation of these changes to the physiological activity of the nucleus is still imperfectly understood.' A description of the nucleus during division is deferred to the following chapter.