Fertilization in Plants

centrosomes and nucleus

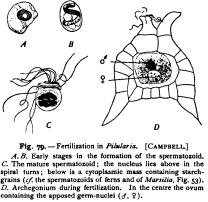

FERTILIZATION IN PLANTS The investigation of fertilization in the plants has always lagged somewhat behind that of the animals, and even at the present time our knowledge of it is less complete, especially in regard to the history of the centrosome and the archoplasmic structures. It is, however, sufficient to show that the process is here essentially of the same nature as in animals in so far as it involves a union of two germ-nuclei derived from the two respective sexes. Many early observers from the time of Pringsheim ('55) onward described a conjugation of cells in the lower plants, but the union of germnuclei, as far as I can find, was first clearly made out in the flowering plants by Strasburger in 1877-8, and carefully described by him in 1884. Schmitz observed a union of the nuclei of the conjugating cells of Spirogyra in 1879, and made similar observations on other algae in 1884. The same has been shown to be true in Museinee and Pteridophytes by Strasburger, Campbell, and others (Fig. 79).

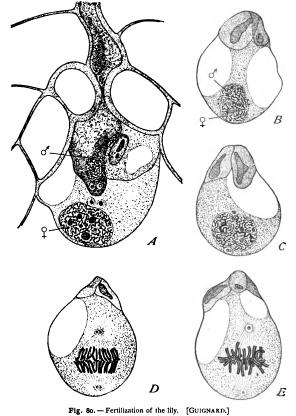

Up to the present time, however, the only thorough investigation of fertilization has been made in the case of the flowering plants, and our knowledge of the process here is due in the first instance to Strasburger ('84, '88) and Guignard ('91), supplemented by the work of Belajeff and Overton. The ovum or oolsphere of the flowering plant is a large, rounded cell containing a large nucleus and numerous minute colourless plastids from which arise, by division, the plastids of the embryo (chromatophores, amyloplasts). The ovum lies in the "embryo-sac," which represents morphologically the female prothallium or sexual generation of the Pteridophyte, and is itself embedded in the ovule within the ovary. The male germ-cell is here non-motile, and is represented by a "generative nucleus," with a small quantity of cytoplasm and two centrosomes (Guignard), lying near the tip of the pollen-tube (Fig. 8o, A) , which is developed as an outgrowth from the pollen-grain and represents, with the latter, a rudimentary male prothallium or sexual generation. The formation A. The tip of the pollen-tube entering the embryo-sac ; below, the ovum (otisphere) with its nucleus at Q and two centrosomes ; at the tip of the pollen-tube the sperm-nucleus (d) with two centrosomes near it. B. Union of the germ-nuclei. C. Later stage of the same, showing the asserted fusion of the centrosomes. E. The first cleavage-figure in the metaphase. D. Early anaphase of the same; precocious division of the centrosomes.

of the pollen-tube, and its growth down through the tissue of the pistil to the ovule, was observed by Amici ('23), Brongniart ('26), and Robert Brown ('31); and in 1833-34 Corda was able to follow its tip through the micropyle into the ovule.' Strasburger ('77-88) first demonstrated the fact that the generative nucleus carried at the tip of the pollen-tube enters the ovum and unites with the egg-nucleus. On the basis of these observations he reached, in 1884, the same conclusion as Hertwig, that the essential phenomena of fertilization is a union of two germ-nuclei, and that the nucleus is the vehicle of hereditary transmission. Strasburger did not, however, observe the centrosome in fertilization. This was accomplished in 1891 by Guignard, who demonstrated in the case of the lily (Li lium Martagon) that the generative nucleus as it enters the egg is accompanied by a small quantity of cytoplasm and by two centrosomes (Fig. 8o). He showed further that the egg also con

tains two centrosomes ; and according to his account the conjugation of the nuclei is accompanied by a conjugation of the centrosomes, as already described.

Guignard also first cleared up the history of the chromosomes, reaching results closely in accord with those of Van Beneden in the case of Ascaris. The two germ-nuclei do not actually fuse, but remain in contact, side by side, and give rise each to one-half the chromosomes of the equatorial plate, precisely as in animals (Fig. 8o). The number of chromosomes from each germ-nucleus is, in the lily, twelve. The later history is identical with that of the animal egg, each chromosome splitting lengthwise, and the halves passing to opposite poles of the spindle. Each daughter-nucleus therefore receives an equal number of chromosomes from the maternal and paternal As in the case of animals (p. 127), the germ-nuclei of plants show marked differences in structure and staining-reaction before their union, though they ultimately become exactly equivalent. Thus, according to Rosen ('92, p. 443), on treatment by fuchsin-methyl-blue It is interesting to note that the botanists of the eighteenth century engaged in the same fantastic controversy regarding the origin of the embryo as that of the zoologists of the time. Moreland (1703), followed by Etienne Francois Geoffroy, Needham, and others, placed himself on the side of Leeuwenhoek and the spermatists, maintaining that the pollen supplied the embryo which entered the ovule through the micropyle. (The latter had been described by Grew in 1672.) It is an interesting fact that even Schleiden adopted a similar view. On the other hand, Adanson (1763) and others maintained that the ovule contained the germ which was excited to development by an aura or vapour emanating from the pollen and entering through the tracheae of the pistil.

2 Guignard's observations on the conjugation of the centrosomes have already been considered at p. 159. They stand at present isolated as the only precise account of the history of the centrosomes in plant-fertilization, and no general conclusions on this subject can therefore at present he drawn.

the male germ-nucleus of phanerogams is " cyanophilous," the female " erythrophilous," as described by Auerbach in animals. Strasburger, while confirming this observation in some cases, finds the reaction to be inconstant, though the germ-nuclei usually show marked differences in their staining-capacity. These are ascribed by Strasburger ('92, '94) to differences in the conditions of nutrition ; by Zacharias and Schwarz to corresponding differences in chemical composition, the male nucleus being in general richer in nuclein, and the female nucleus poorer. This distinction disappears during fertilization, and Strasburger has observed, in the case of gymnosperms (after treatment with a mixture of fuchsin-iodine-green) that the paternal nucleus, which is at first " cyanophilous," becomes " erythrophilous," like the egg-nucleus before the pollen-tube has reached the egg. Within the egg both stain exactly alike. These facts indicate, as Strasburger insists, that the differences between the germ-nuclei of plants are as in animals of a temporary and non-essential character.