The Germ Cells

germ-cells and body

THE GERM CELLS " Not all the progeny of the primary impregnated germ-cells are required for the formation of the body in all animals; certain of the derivative germ-cells may remain unchanged and become included in that body which has been composed of their metamorphosed and diversely combined or confluent brethren; so included, any derivative germ-cell may commence and repeat the same processes of growth by inhibition and of propagation by spontaneous fission as those to which itself owed its origin; followed by metamorphoses and combinations of the germ-masses so produced, which concur to the development of another individual." RICHARD OWEN.' " Es theilt sich demgemass das befruchtete Ei in das Zellenmaterial des Individuums and in die Zellen fib die Erhaltung der Art." M. NUSSBAUNI.2 The germ from which every living form arises is a single cell, derived by the division of a parent-cell of the preceding generation. In the unicellular plants and animals this fact appears in its simplest form as the fission of the entire parent-body to form two new and separate individuals like itself. In all the multicellular types the cells of the body sooner or later become differentiated into two groups which as a matter of practical convenience may be sharply distinguished from one another. These are, to use Weismann's terms : the somatic cells, which are differentiated into various tissues by which the functions of individual life are performed and which collectively form the " body," and (2) the germ-cells, which are of minor significance for the individual life and are destined to give rise to new individuals by detachment from the body. It must, however, be borne in mind that the distinction between germ-cells and somatic cells is not absolute, as some naturalists have maintained, but only relative. The cells of both groups have a common origin in the parent germcell ; both arise through mitotic cell-division during the cleavage of the ovum or in the later stages of development ; both have essentially the same structure and both may have the same power of development, for there are many cases in which a small fragment of the body consisting of only a few somatic cells, perhaps only of one, may give rise by regeneration to a complete body. The distinction between somatic and germ-cells is an expression of the physiological division of labour ; and while it is no doubt the most fundamental and important differentiation in the multicellular body, it is nevertheless to be regarded as differing only in degree, not in kind, from the distinctions between the various kinds of somatic cells.

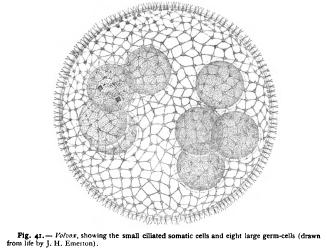

In the lowest multicellular forms, such as Volvox (Fig. 41), the differentiation appears in a very clear form. Here the body consists of a hollow sphere the walls of which consist of two kinds of cells. The very numerous smaller cells are devoted to the functions of nutrition and locomotion, and sooner or later die. Eight or more larger

cells are set aside as germ-cells, each of which by progressive fission may form a new individual like the parent. In this case the germcells are simply scattered about among the somatic cells, and no special sexual organs exist. In all the higher types the germ-cells are more or less definitely aggregated in groups, supported and nourished by somatic cells specially set apart for that purpose and forming distinct sexual organs, the ovaries and spermaries or their equivalents. Within these organs the germ-cells are carried, protected, and nourished ; and here they undergo various differentiations to prepare them for their future functions.

In the earlier stages of embryological development the progenitors of the germ-cells are exactly alike in the two sexes and are indistinguishable from the surrounding somatic cells. As development proceeds, they are first differentiated from the somatic cells and then diverge very widely in the two sexes, undergoing remarkable transformations of structure to fit them for their specific functions. The structural difference thus brought about between the germ-cells is, however, only the result of physiological division of labour. The female germ-cell, or ovum, supplies most of the material for the body of the embryo and stores the food by which it is nourished. It is therefore very large, contains a great amount of cytoplasm more or less laden with food-matter (yolk or deutoplasm), and in many cases becomes surrounded by membranes or other envelopes for the protection of the developing embryo. On the whole, therefore, the early life of the ovum is devoted to the accumulation of cytoplasm and the storage of potential energy, and its nutritive processes are largely constructive or anabolic. On the other hand, the male germ-cell or spermatozoon contributes to the mass of the embryo only a very small amount of substance, comprising as a rule only a single nucleus and a centrosome. It is thus relieved from the drudgery of making and storing food and providing protection for the embryo, and is provided with only sufficient cytoplasm to form a locomotor apparatus, usually in the form of one or more cilia, by which it seeks the ovum. It is therefore very small, performs active movements, and its metabolism is characterized by the predominance of the destructive or katabolic processes by which the energy necessary for these movements is set free.' When finally matured, therefore, the ovum and spermatozoon have no external resemblance ; and while Schwann recognized, though somewhat doubtfully, the fact that the ovum is a cell, it was not until many years afterwards that the spermatozoon was proved to be of the same nature.