Chemical Relations of Nucleus and Cytoplasm

acid and nucleic

The Nuclein Series

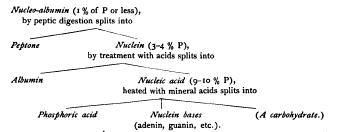

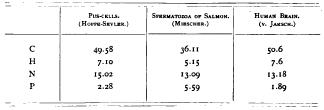

Nuclein was first isolated and named by Miescher in 1871, by subjecting cells to artificial gastric digestion. The cytoplasm is thus digested, leaving only the nuclei ; and in some cases, for instance pus-cells and spermatozoa, it is possible by this method to procure large quantities of nuclear substance for accurate quantitative analysis. The results of analysis show it to be a complex albuminoid substance, rich in phosphorus, for which Miescher gave the chemical formula Later analyses gave somewhat discordant results, as appears in the following table of percentage-compositions These differences led to the opinion, first expressed by HoppeSeyler, and confirmed by later investigations, that there are several varieties of nuclein which form a group having certain characters in common. Altmann ('89) opened the way to an understanding of the matter by showing that " nuclein " may be split up into two substances ; namely, (I) an organic acid rich in phosphorus, to which he gave the name nucleic acid, and (2) a form of albumin. Moreover, the nuclein may be synthetically formed by the re-combination of these two substances. Pure nucleic acid contains no sulphur, a high percentage of phosphorus (above 9 %), and no albumin. By adding it to a solution of albumin a precipitate is formed which contains sulphur, a lower percentage of phosphorus, and has the chemical characters of nuclein. This indicates that the discordant results in the analyses of nuclein, referred to above, were probably due to varying proportions of the two constituents ; and Altmann suggested that the " nuclein " of spermatozoa, which contains no sulphur and a maximum of phosphorus (over 9.5 %), might be uncombined nucleic acid itself. Kossel accordingly drew the conclusion, based on his own work as well as that of Liebermann, Altmann, Malfatti, and others, that " what the histologists designate as chromatin consists essentially of combinations of nucleic acid with more or less albumin, and in some cases may even be free nucleic acid. The less the percentage of albumin in these compounds, the nearer do their properties approach those of pure nucleic acid, and we may assume that the percentage of albumin in the chromatin of the same nucleus may vary according to physiological conditions." 1 In the same year Halliburton, following in part HoppeSeyler, stated the same view as follows. The so-called " nucleins " form a series leading downward from nucleic acid thus : — (I) Those containing no albumin and a maximum (9–To %) of phosphorus (pure nucleic acid). Nuclei of spermatozoa.

(2) Those containing little albumin and rich in phosphorus. Chromatin of ordinary nuclei.

(3) Those with a greater proportion of albumin — a series of substances in which may probably be included pyrenin (nucleoli) and plastin(linin). These graduate into (4) Those containing a minimum (o.5 to i %) of phosphorus the nucleo-albumins, which occur both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm (vitellin, caseinogin, etc.).

Finally, we reach the globulins and albumins, especially characteristic of the cell-substance, and containing no nucleic acid. " We thus pass by a gradual transition (from the nucleo-albumins) to the other proteid constituents of the cell, the cell-globulins, which contain no phosphorus whatever, and to the products of cell-activity, such as the proteids of serum and of egg-white, which are also principally pho'sphorus-free." 2 Further, " in the processes of vital activity there are changing relations between the phosphorized constituents of the nucleus, just as in all metabolic processes there is a continual interchange, some constituents being elaborated, others breaking down into simpler products."' These conclusions established a probability that the chemical differences between chromatin and cytoplasm, striking and constant as they are, are differences of degree only ; and they opened the way to a more precise investigation of the physiological role of nucleus and cytoplasm in metabolism.

Staining-reactions of the Nuclein-series

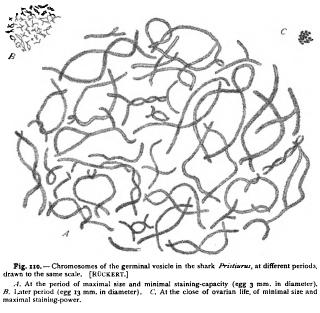

We may now bring these facts into relation with the stainingreactions of chromatin and cytoplasm when treated with the aniline dyes. These dyes are divided into two main viz. the " basic " anilines and the " acid " anilines, the colouring-matter playing the part of a base in the former and of an acid in the latter. The basic anilines (e.g. methyl-green, Bismarck brown, saffranin) are in general " nuclear stains," having a strong affinity for chromatin, while the acid anilines (acid fuchsin, Congo red, eosin, etc.) are "plasma-stains," colouring more especially the cytoplasmic elements. We owe to Malfatti and Lilienfeld the very interesting discovery that the various members of the nuclein series show an affinity for the basic dyes in direct proportion to the amount of nucleic acid (as measured by the amount of phosphorus) they contain. Thus the nuclei of spermatozoa, known to consist of nearly pure nucleic acid, stain most intensely with basic dyes, those of ordinary tissue-cells, which contain less phosphorus, less intensely. Malfatti ('91) tested various members of the nuclein-series, synthetically produced as combinations of egg-albumin and nucleic acid from yeast, with a mixture of red acid fuchsin and basic methyl-green. With this combination free nucleic acid was coloured pure green, nucleins containing less phosphorus became bluish-violet, those with little or no phosphorus pure red. Lilienfeld's more precise experiments in this direction ('92, '93) led to similar results. His starting-point was given by the results of Kossel's researches on the relations of the nuclein group, which are expressed as follows Now, according to Kossel and Lilienfeld, the principal nucleoalbumin (nucleo-proteid) in the nucleus of leucocytes is nudeo-histon, containing about 3 % of phosphorus, which may be split into a form of nuclein playing the part of an acid, and an albuminoid base, the piston of Kossel ; the nuclein may in turn be split into albumin and nucleic acid. These four substances —albumin, nucleo-histon, nuclein, nucleic acid — thus form a series in which the proportion of phosphorus, i.e. of nucleic acid, successively increases from zero to 9-10 %. If the members of this series be treated with the same mixture of red acid fuchsin and basic methyl-green, the result is as follows. Albumin (egg-albumin) is stained red, nucleo-histon greenish-blue, nuclein bluish-green, nucleic acid intense green. " We see, therefore, that the principle that determines the staining of the nuclear substances is always the nucleic acid. All the nuclear substances, from those richest in albumin to those poorest in it, or containing none, assume the tone of the nuclear (i.e. basic) stain, but the combined albumin modifies the green more or less towards Lilienfeld explains the fact that chromatin in the cell-nucleus seldom appears pure green on the assumption, supported by many facts, that the proportion of nucleic acid and albumin vary with different physiological conditions, and he suggests further that the intense staining-power of the chromosomes during mitosis is probably due to the fact that they consist, like the chromatin of spermatozoa, of pure or nearly pure nucleic acid. Very interesting and convincing is a comparison of the foregoing staining-reactions with those given by a mixture of a red basic dye (saffranin) and a green acid one (" light green "). With this combination an effect is given which reverses that of the Biondi-Ehrlich mixture ; i.e. the nuclein is coloured' red, the albumin green. This is a beautiful demonstration of the fact that staining-reagents cannot be logically classified according to colour, but only according to their chemical nature. Such terms as " erythrophilous," " cyanophilous," and the like have therefore no meaning apart from the chemical composition both of the dye and of the substance stained.' The constancy and accuracy of these reactions await further test, and until this has been carried out we should be careful not to place too implicit a trust in the staining-reactions as an indication of chemical nature, especially as they are known to be affected by the preceding mode of fixation. They afford, nevertheless, a rough method for the micro-chemical test of the proportion of nucleic acid present in the nuclear structures, and this in the hands of Heidenhain has led to some suggestive results. Leucocytes stained with the BiondiEhrlich mixture of acid fuchsin and methyl-green show the following reactions. Cytoplasm, centrosome, attraction-sphere, astral rays, and spindle-fibres are stained pure red. The nuclear substance shows a very sharp differentiation. The chromatic network and the chromosomes of the mitotic figure are green. The linin-substance and the true nucleoli or plasmosomes appear red, like the cytoplasm. The linin-network of leucocytes is stated by Heidenhain to consist of two elements, namely, of red granules or microsomes suspended in a colourless network. The latter alone is called " linin " by Heidenhain. To the red granules is applied the term " oxychromatin," while the green substance of the ordinary chromatic network, forming the " chromatin " of Flemming, is called " basichromatin." 2 Morphologically, the granules of both kinds are exactly and in many cases the oxychromatin-granules are found not only in the "achromatic " nuclear network, but also intermingled with the basichromatin-granules of the chromatic network. Collating these results with those of the physiological chemists, Heidenhain concludes that basichromatin is a substance rich in phosphorus (i.e. nucleic acid), oxychromatin a substance poor in phosphorus, and that, further, " basichromatin and oxychromatin are by no means to be regarded as permanent unchangeable bodies, but may change their colour-reactions by combining with or giving off phosphorus." In other words, " the affinity of the chromatophilous microsomes of the nuclear network for basic and acid aniline dyes are regulated by certain physiological conditions of the nucleus or of the cell." 4 This conclusion, which is entirely in harmony with the statements of Kossel and Halliburton quoted above, opens up the most interesting questions regarding the periodic changes in the nucleus. The staining-power of chromatin is at a maximum when in the preparatory stages of mitosis (spireme-thread, chromosomes). During the ensuing growth of the nucleus it always diminishes, suggesting that a combination with albumin has taken place. This is illustrated in a very striking way by the history of the egg-nucleus or germinal vesicle, which exhibits the nuclear changes on a large scale. It has long been known that the chromatin of this nucleus undergoes great changes during the growth of the egg, and several observers have maintained its entire disappearance at one period. Ruckert first carefully traced out the history of the chromatin in detail in the eggs of sharks, and his general results have since been confirmed by Born in the eggs of Triton. In the shark Pristiurus Ruckert ('92, i) finds that the chromosomes, which persist throughout the entire growth-period of the egg, undergo the following changes (Fig. 110) : At a very early stage they are small, and stain intensely with nuclear dyes. During the growth of the egg they undergo a great increase in size, and progressively lose their staining-capacity. At the same time their surface is enormously increased by the development of long threads which grow out in every direction from the central axis (Fig. 110, A) . As the egg approaches its full size, the chromosomes rapidly diminish in size, the radiating threads disappear, and the staining-capacity increases (Fig. I to, B) . They are finally again reduced to minute intensely staining bodies which enter into the equatorial plate of the first polar mitotic figure (Fig. no, C). How great the change of volume is may be seen from the following figures. At the beginning the chromosomes measure, at most, 12 (about 1/2000 in.) in length and p. in diameter. At the height of their development they are almost eight times their original length and twenty times their original diameter. In the final period they are but 2 z in length and 1 u in diameter. These measurements show a change of volume so enormous, even after making due allowance for the loose structure of the large chromosomes, that it cannot be accounted for by mere swelling or shrinkage. The chromosomes evidently absorb a large amount of matter, combine with it to form a substance of diminished stainingcapacity, and finally give off matter, leaving an intensely staining substance behind. As Ruckert points out, the great increase of surface in the chromosomes is adapted to facilitate an exchange of material between the chromatin and the surrounding substance; and he concludes that the coincidence between the growth of the chromosomes and that of the egg, points to an intimate connection between the nuclear activity and the formative energy of the cytoplasm.