The Early History of the Germ-Nuclei

chromosomes and ruckert

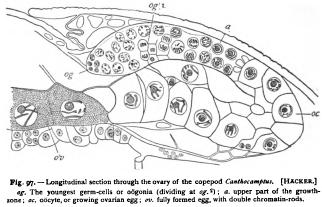

THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE GERM-NUCLEI We may for the present defer a consideration of accounts of reduction differing from the two already described and pass on to a consideration of the earlier history of the germ-nuclei. A considerable number of observers are now agreed that the primary chromatinrods appear at a very early period in the germinal vesicle and are longitudinally split from the first. (Hacker, vom Rath, Ruckert, in copepods ; Ruckert in selachians ; Born and Fick in amphibia ; Holl in the chick ; Ruckert in the rabbit.) Hacker ('92, 2) made the interesting discovery that in some of the copepods (Canthocamptus, Cyclops) these double rods could be traced back continuously to a double spireme-thread, following immediately upon the division of the last generation of oogonia, and that at no period is a true reticulum formed in the germinal vesicle (Fig. 97). In the following year Ruckert ('93, 2) made a precisely similar discovery in the case of selachians. After division of the last generation of oogonia the daughter-chromosomes do not give rise to a reticulum, but split lengthwise, and persist in this condition throughout the entire growth-period of the egg. Ruckert therefore concluded that the germinal vesicle of the selachians is to be regarded as a " daughter-spireme of the oogonium (Ur-ei) grown to enormous dimensions, the chromosomes of which are doubled and arranged in In the following year vom Rath, following out the earlier work of Flemming, discovered an exactly analogous fact in the spermatogenesis of the salamander. The tetrads were here traced back to double chromatin-rods, individually identical with the daughter-chromosomes of the preceding spermatogonium-division, which split lengthwise during the anaphase and pass into the spermatocyte-nucleus without forming a reticulum. Flemming had observed in 1887 that these daughter-chromosomes split in the anaphase, but could not determine their further history. Vom Rath found that each double daughter-chromosome breaks in two at the apex to form a tetrad, which passes into the ensuing spermatocyte without the intervention of a resting It is clear that in such cases the " pseudo-reduction " must take place at an earlier period than the penultimate generation of cells.

In the salamander Flemming ('87) found that the " chromosomes " of the spermatogonia appeared in the reduced number (twelve) in at least three cell-generations preceding the penultimate. Vom Rath ('93) traced the pseudo-reduction in both sexes back to much earlier stages, not only in the larvae, but even in the embryo (!). This very remarkable discovery showed that the pseudo-reduction might appear in the early progenitors of the germ-cells during embryonic life—perhaps even during the cleavage. This conjecture has apparently been substantiated by Hacker ('95, 3), who finds that in Cyclops brevicornis the reduced number of chromosomes (twelve) appears in the primordial germ-cells which are differentiated in the blastula-stage (Fig. 56). He adds the interesting discovery that in this form the somatic nuclei of the cleavage-stages show the same number, and hence concludes that all the chromosomes of these stages are bivalent. As development proceeds, the germ-cells retain this character, while the somatic cells acquire the usual number (twenty-four)— a process which, if the conception of bivalent chromosomes be valid, must consist in the division of each bivalent rod into its two elements. We have here a wholly new light on the historical origin of reduction ; for the pseudoreduction of the germ-nuclei seems to be in this case a persistence of the embryonic condition, and we may therefore hope for a future explanation of the process by which it has in other cases been deferred until the penultimate cell-generation, as is certainly the fact in The foregoing facts pave the way to an examination of reduction in the plants, to which we now proceed.