Critique of the Roux-Weismann Theory

blastomeres and division

CRITIQUE OF THE ROUX-WEISMANN THEORY From a logical point of view the Roux-Weismann theory is unassailable. Its fundamental weakness is its quasi-metaphysical character, which indeed almost places it outside the sphere of legitimate scientific hypothesis. Not a single visible phenomenon of cell-division gives even a remote suggestion of qualitative division. All the facts, on the contrary, indicate that the division of the chromatin is carried out with the most exact equality. The theory of qualitative division was suggested by a totally different order of phenomena, and is an explanation constructed ad hoc. Roux, it is true, was led to the hypothesis through an examination of mitosis ; but it is safe to say that he would never have maintained in the same breath that mitosis is expressly designed for quantitative and also for qualitative division, had he fixed his attention on the actual phenomena of mitosis alone. The hypothesis is in fact as complete an a priori assumption as any that the history of scholasticism can show, and every fact opposed to it has been met by equally baseless subsidiary hypotheses, which, like their principal, relate to matters beyond the reach of observation.

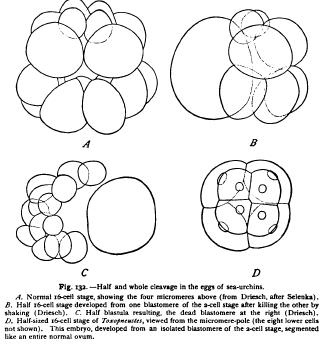

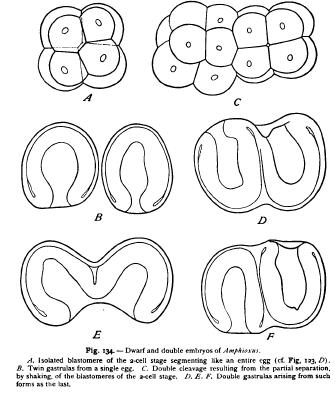

Such an hypothesis cannot be actually overturned by an appeal to fact. When, however, we make such an appeal, the improbability of the hypothesis becomes so great that it loses all semblance of reality. It is rather remarkable that Roux himself led the way in this direction. In the course of his observations on the development of a halfembryo from one of the blastomeres of the two-cell stage he determined the significant fact that the half-embryo afterwards regenerated the missing half, and gave rise to a complete embryo. Essentially the same result was reached by later observers, both in the frog (Endres, Walter, Morgan) and in a number of other animals, with the important addition that the half-formation is sometimes characteristic of only the earliest stages and may be entirely suppressed. In 1891 Driesch was able to follow out the development of isolated blastomeres of sea-urchin eggs separated by shaking to pieces the twocell and four-cell stages. Blastomeres thus isolated segment as if still forming part of an entire larva, and give rise to a half- (or quar blastula (Fig. 132). The opening soon closes, however, to form a small complete blastula, and the resulting gastrula and Pluteus larva is a perfectly formed dwarf of only half (or quarter) the normal size.

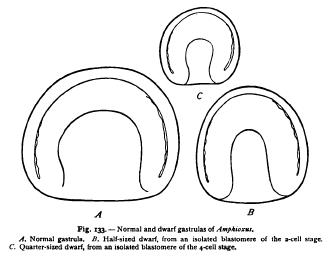

Incompletely separated blastomeres gave rise to double embryos like the Siamese twins. Shortly afterwards the writer obtained similar result in the case of Amphioxus, but here the isolated blastomere segments from the beginning like an entire ovum of diminished size (Figs. 133, 124). A like result has since been reached by Morgan ('95, 2) in the teleost fishes, by Herlitzka ('95) in Triton, and by Zoja ('95, I) in the medusae. The last-named experimenter was able to obtain perfect embryos not only from blastomeres of the two-cell and fourcell stages, but from eight-cell and even from sixteen-cell stages, the dwarfs in the last case being but -1/16 the normal size ! These experiments gave a fatal blow to the entire Roux-Weismann theory ; for the results showed that the cleavage of the ovum does not in these cases sunder different materials, either nuclear or cytoplasmic, but only splits it up into a number of similar parts, each of which may give rise to an entire body of diminished size.

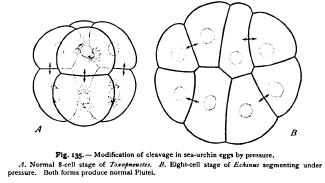

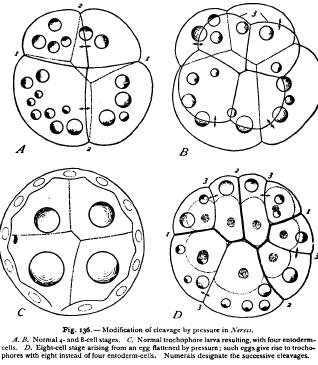

The theory of qualitative nuclear division has been practically disproved in another way by Driesch, through the pressure-experiments already mentioned at p. 275. Following the earlier experiments of Pfluger and Roux on the frog's egg, Driesch subjected segmenting eggs of the sea-urchin to pressure, and thus obtained flat plates of cells in which the arrangement of the nuclei differed totally from the normal (Fig. 134) ; yet such eggs when released from pressure continue to segment, without rearrangement of the nuclei, and give rise to perfectly normal larvae. I have repeated these experiments not only with sea-urchin eggs, but also with those of an annelid (Nereis), which yield a very convincing result, since in this case the histological differentiation of the cells appears very early. In the normal development of this animal the archenteron arises from four large cells or macromeres (entomeres), which remain after the successive formation of three quartets of micromeres (ectomeres) and the parent-cell of the mesoblast. After the primary differentiation of the germ-layers the four entomeres do not divide again until a very late period (freeswimming trochophore), and their substance always retains a characteristic appearance, differing from that of the other blastomeres in its pale non-granular character and in the presence of large oil-drops.