The External Conditions of Development

environment and normal

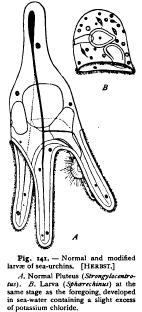

THE EXTERNAL CONDITIONS OF DEVELOPMENT We have thus far considered only the internal conditions of development which are progressively created by the germ-cell itself. We must now briefly glance at the external conditions afforded by the environment of the embryo. That development is conditioned by the external environment is obvious. But we have only recently come to realize how intimate the relation is ; and it has been especially the service of Loeb, Herbst, and Driesch to show how essential a part is played by the environment in the development of specific organic forms. The limits of this work will not admit of any adequate review of the vast array of known facts in this field, for which the reader is referred to the works especially of Herbst. I shall only consider one or two cases which may serve to bring out the general principle that they involve. Every living organism at every stage of its existence reacts to its environment by physiological and morphological changes. The developing embryo, like the adult, is a moving equilibrium—a product of the response of the inherited organization to the external stimuli working upon it. If these stimuli be altered, development is altered. This is beautifully shown by the experiments of Herbst and others on the development of seaurchins. Pouchet and Chabry showed that if the embryos of these animals be made to develop in sea-water containing no lime-salts, the larva fails to develop not only its calcareous skeleton, but also its ciliated arms, and a larva thus results that resembles in some particulars an entirely different specific form ; namely, the Tornaria larva of Balanoglossus. This result is not due simply to the lack of necessary material ; for Herbst showed that the same result is attained if a slight excess of potassium chloride be added to sea-water containing the normal amount of lime (Fig. 141). In the latter case the specific metabolism of the protoplasm is altered by a particular chemical stimulus, and a new form results.

The changes thus caused by slight chemical alterations in the water may be still more profound. Herbst ('92) observed, for example, that when the water contains a very small percentage of lithium chloride, the blastula of sea-urchins fails to invaginate to form a typical gastrula, but evaginates to form an hour-glass-shaped larva, one half of which represents the archenteron, the other half the ectoblast. Moreover, a much larger number of the blastula-cells undergo the differentiation into entoblast than in the normal development, the ectoblast sometimes becoming greatly reduced and occasionally disappearing altogether, so that the entire blastula is differentiated into cells having the histological character of the normal entoblast ! One of the most fundamental of embryonic differentiations is thus shown to be intimately conditioned by the chemical environment.

The observations of botanists on the production of roots and other structures as the result of local stimuli are familiar to all. Loeb's interesting experiments on hydroids gave a similar result ('91). It has long been known that Tubularia, like many other hydroids, has the power to regenerate its " head " — i.e. hypostome, mouth, and tacles — after decapitation. Loeb proved that in this case the power to form a new head is conditioned by the environment. For if a Tubularia stem be cut off at both ends and inserted in the sand upside down, i.e. with the oral end buried, a new head is regenerated at the free (formerly aboral) end. Moreover, if such a piece be suspended in the water by its middle point, a new head is produced at eaeh end (Fig. 142); while if both ends be buried in the sand, neither end regenerates. This proves in the clearest manner that in this case the power to form a definite complicated structure is called forth by the stimulus of the external environment.

These cases must suffice for our purpose. They prove incontestably that normal development is in a greater or less decree the response of the developing organism to normal conditions ; and they show that we cannot hope to solve the problems of development without reckoning with these conditions. But neither can we regard specific forms of development as directly caused by the external conditions ; for the egg of a fish and that of a polyp develop, side by side, in the same drop of water, under identical conditions, each into its predestined form. Every step of development is a physiological reaction, involving a long and complex chain of cause and effect between the stimulus and the response. The character of the response is determined not by the stimulus, but by the inherited organization. While, therefore, the study of the external conditions is essential to the analysis of embryological phenomena, it serves only to reveal the mode of action of the idioplasm and gives but a dim insight into its ultimate nature.