Gastropoda

GASTROPODA, a large group of invertebrate animals ranked as a class of the phylum Mollusca and represented by such familiar forms as the limpet, the whelk, the common snail and slug. There is no single English name which can be given to this group. The land and freshwater forms which have shells may all be termed "snails" and the shell-less land forms "slugs," and by a reasonable usage the name "snails" or "sea-snails" may be given to marine gastropoda with shells (whelks, periwinkles, etc.), and the shell less marine forms (Nudibranchia, etc.) may be called "slugs" or "sea-slugs." The gastropoda are primarily distin guished from other molluscs by their shell, which is a single structure and is spirally coiled, at least in the larval state. In many gastropoda, however, it is very much modified in the adult and, though it is spiral in a large number of genera, it may lose this appearance and become (e.g.) cup-shaped or tubu lar. In some forms it is covered over by the mantle and de generate, and it may also be entirely absent. The gastropoda are also distinguished from other molluscs by their asymmetrical organization. The latter is brought about by a process which takes place in larval development, during which the anus and the organs adjacent to the latter are moved forwards ven trally from their originally posterior position and then twisted throueh 18o°. so that they come to lie ahnve and to nnP Cidp of the head. The flexure of the intestine is a phenomenon seen in other molluscs; the twisting or "torsion" of the anal complex is peculiar to gastropods, and it is believed to bring about the asym metry mentioned above, the chief feature of which is the atrophy or the complete disappearance of the kidney, gill and auricle originally situated on the left side of the body, those of the original right side persisting in a more or less unmodified condition. The clearly defined and well-developed head is likewise distinctive. The gastropoda constitute the largest class of molluscs and num ber some 30,000 living species, which range in size from giant whelk-like forms 2f t. in length, down to minute species of Vertigo barely a millimetre long in the adult state. An enigmatic fossil from the Wealden of Kent (Dinocochlea ingens) measuring over 6f t. in length has been described as a fossil gastropod.

In all probability the earliest gastropods were marine animals and they now constitute an important part of the marine fauna. They have also populated fresh water and land, and the familiar Helicidae, the Zonitidae and mulidae are among the largest groups of land invertebrates. In general, their range of habitat is diversified. They are found at very great depths in the sea as well as in the shallower water, and the pelagic gastropods (Pteropoda and Heteropoda) form part of the marine plankton (minute floating organisms). The freshwater and terrestrial poda occupy a great variety of habitats and as a whole are to be reckoned as a very adaptable group, though the need for mois ture and lime salts renders them less universally distributed than, e.g., millepedes and Collembola.

Generally speaking, gastropods are sedentary, inactive animals that rely on their hard shells and unobtrusive habits for protec tion. The cumbrous shell and the absence of a jointed skele ton render them slow in their movements. On the other hand, they are capable of very considerable muscular exertion and tend to be very tenacious of life. A limited number of genera are more active and mobile and have taken to swimming, climbing and burrowing. Many marine gastropods and the majority of the terrestrial and freshwater forms feed upon plants or on organic debris, and such a diet was no doubt characteristic of the primi tive gastropod stock. Several groups, however, have become carnivorous and are modified accordingly in habits and structure.

Classification.—The classification of the gastropoda has undergone many changes in the past. Even at the present time there is no universally accepted system so far as the main sub divisions are concerned, although there is a general measure of agreement as to the composition of certain of the lesser groups.

The class Gastropoda, including the orders Nudibranchiata, Tectibranchiata and Pulmonata, was created by Cuvier in later he created the Pteropoda as equal in rank with the Gastro poda. In 1812 Lamarck created the group Heteropoda, ranking it also equal with Gastropoda. In 1846-48 Milne-Edwards estab lished the orders Opisthobranchiata and Prosobranchiata. The Pteropoda were held as a distinct class until Pelseneer in 1888 showed their affinities to the Opisthobranchiata.

The diversity of opinion about the main subdivisions may be taken to imply that any natural groups of these dimensions (sub classes, orders) that may exist in the class have not yet been made apparent by morphological re search. Nevertheless, certain broad groupings are recognized by those authors who in the last two decades have subjected the class to comprehensive treatment.

It will be convenient to contrast three such systems which have been proposed by Pelseneer, Simroth and Thiele respectively.

Different as these three schemes appear at the offset, they tend in fact to recognize the same main groupings. For table of systems see top of page 6o.

The Streptoneura of Pelseneer contain precisely the same fam ilies (limpets, trochids, periwinkles, whelks, etc.) as do the Prosobranchia of Simroth and Thiele. The rest of the class is treated as a single sub-class by Pelseneer. Thiele divides them into two sub-classes (as also seems to be the intention of Hoff man, who is continuing Simroth's treatise in Bronn's Tierreich).

But this does not involve any re-arrangement of the contents of Pelseneer's Euthyneura, as the latter are divided into two orders, equivalent in their contents to Thiele's sub-classes. In short, both authors recognize the distinction between the Opis thobranchia and the air-breathing pulmonata. Thiele's promo tion of these two groups to the rank of sub-classes is advantageous, however, as it emphasizes the marked structural and bionomic differences tween these groups. It is true that they semble each other in certain distinctive features (e.g., they are hermaphrodite and the visceral complex is detorted) in which they both differ from the Streptoneura. But they are otherwise very clearly defined and have a radically dissimilar evolutionary history.

Thiele's Archaeogastropoda contain the same families as Pelseneer's Aspido branchia and Simroth's Scutibranchia. His Mesogastropoda are Pelseneer's Taenio glossa and his Stenoglossa are equivalent to Pelseneer's sub-order of that name. With regard to the status given to these groups Pelseneer's scheme seems at present more rational. While Thiele's elevation of the Stenoglossa to the rank of an order is to some extent justified by the marked specialization of these forms as carnivores and carrion-feeders, it leaves the Taenioglossa, a large and miscellaneous group with too great an appearance of uni formity. Probably Thiele's rating of the Stenoglossa is justifiable, and what is required is a more complete knowledge of the rela tionships of families constituting the Taenioglossa.

Little can be said concerning the numerous minor divisions.

A great deal of work remains to be done in elucidating the con stitution and relationships of families, the structure of which is imperfectly known. Many of the minor groups are probably very far from representing natural associations. The work of Pilsbry (1909-28) on the enormous group of land pulmonata has gone a long way towards disentangling the chaotic assemblages originally treated as "Helicidae," "Bulimuli dae" and "Zonitidae," and the course of pulmonate evolution is becoming correspondingly clearer to us. But even so, this large and unwieldy order is in need of comprehensive treatment along bionomic as well as morphologi cal lines.

The gastropoda are divisible, as we have already seen, into a large number of groups, each dis tinguished by anatomical and bionomic peculiarities. The sig nificances of these divisions will be easier to grasp, if the main evolutionary tendencies that have been manifested within the class are briefly indicated in advance.

The details of gastropod structure and morphology are well de scribed in the standard text-books on this subject, and the descrip tion given here consists of a selection of such of the more im portant modifications as illustrate the main evolutionary changes within the group.

The most primitive of living gastropods are sedentary marine animals which feed upon algae, sea-weeds or organic debris. They creep about by means of a flattened foot and rely for protection on an external shell, which is usually coiled in the adult. Their internal organization, though it is affected by the "torsion" already mentioned as far as the visceral ner vous commissure and alimentary canal are concerned, is still more or less symmetrical. Pleurotomaria, Fissurella and Haliotis among the Rhipidoglossa exemplify this type of organization. In the course of evolution the main departures from the latter are as follows : (I) The visceral complex (heart, gills and kidneys) be comes asymmetrical through the atrophy and disappearance of those of the above named organs which are situated on the right side of the adult body. (2) The shell may become internal and degenerate and finally disappear and a secondary external sym metry may be established. (3) A terrestrial and air-breathing mode of life has been adopted independently by several groups. (4) A carnivorous or carrion-eating habit has been acquired on several occasions. (S) The creeping mode of progression has been aband oned by certain families in favour of swimming and floating or of a truly sessile (adherent) mode of life.

These by no means exhaust the list of specialization exhibited by the class ; but they are the most frequent and lead to the most striking modifications of structure.

External Features and General Organization.

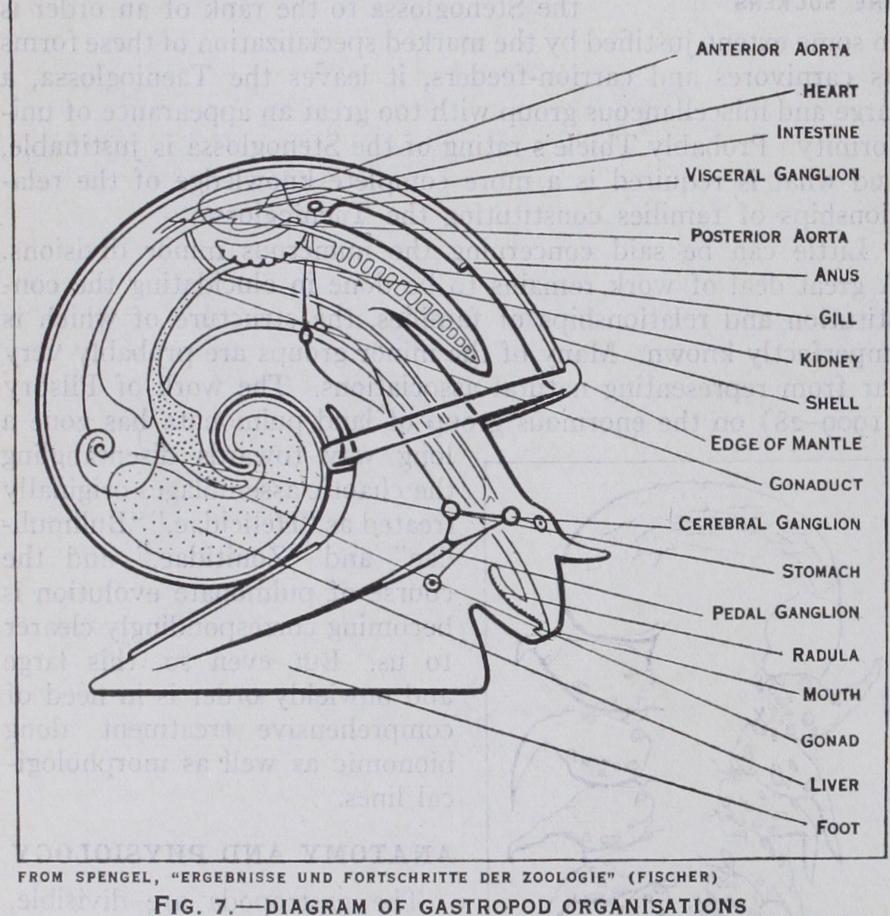

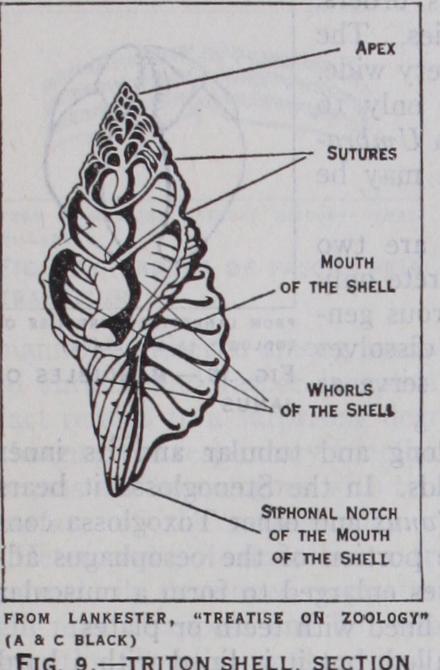

The body of a gastropod is divisible, like that of nearly all molluscs, into four main parts—the visceral sac, the mantle which covers the latter, the head and the foot. The morphological unity of the head and foot has been suggested by Naef, and this subject is discussed in the article MOLLUSCA. The whole animal may be visualized as having an elongate and worm-like body with the head and foot at one end. The greater part of the body is spirally coiled, and the coiled portion (the visceral sac) is sheathed in a fleshy covering, the mantle, which projects as a free fold at the anterior end and hangs down like a skirt around the head and foot. In the cavity thus formed between the mantle and head the function of respiration is normally carried out either by gills or by a lung. In the former case the mantle cavity is largely open to the exterior ; in the second the edge of the mantle is adherent to the "neck," a small hole (the pneumostome) being left for the admission of air into the lung. In certain Rhipidoglossa the mantle edge is not complete anteriorly and dorsally, but is interrupted either by a longitudinal slit or a series of holes probably represent ing a slit, the edges of which have fused.The mantle secretes a shell which is formed in a single piece and is in most cases spirally coiled. The minute structure of the shell and its chemical composition is described in the article MOLLUSCA. In individual development the shell appears in the embryo as a plate or cap-like rudiment which becomes coiled and grows in size by the deposition of mineral salts round the edge of the open end (aperture) . It is likely that the forerunners of the gastropoda had a cap-shaped shell in the adult state.

In the most archaic representatives of the class, however (e.g. Bellerophon, among the extinct Cambrian genera and Pleuroto maria among living- forms) the shell is coiled. It is worthy of note that in Bellerophon the shell is not of an elongate or screw like spiral shape, its coils being all in one plane (planospiral), like that of the primitive cephalopod Nautilus. The modifications of the adult shell are complex and manifold. The general plan and the terminology employed in describing shells are shown in fig. 9 and the various modifications are described and illustrated in text books and conchological treatises. It is sufficient here to allude to the most important change that is encountered in the class. The shell, which is to be regarded as primitively spiral, becomes unwound and secondarily cap-shaped in many Streptoneura (Patella, Capulus). Furthermore, the edges of the mantle may grow over the shell and cover a large part of its surface. This condition is found in such genera as Fissurella, Cypraea, and Marginella among the Streptoneura and in various Opistho branchia (Aplysia) and Pulmonata (Vitrina). The overgrowth of the mantle may be complete and the shell is thus internal and degenerate (Lamellariidae and slug-like Pulmonata). Finally, the shell may disappear entirely (Titiscania, many nudibranchs, Oncidium). This progressive atrophy of the shell occurs in many groups of gastropods. Al though it may become of advan tage to the animal as allowing it greater freedom of movement, the loss of the shell is to be re garded at least at the offset as an innate tendency of the class and probably of the molluscan phy lum as a whole.

The head in the gastropoda is well developed and clearly defined from the rest of the body to which it is connected by a mobile "neck." It is usually provided with sense organs, a snout or muzzle and one or two pairs of tentacles. The foot is a powerful muscular organ. Usually it is rather elongate and has a flat sur face suitable for a creeping gait.

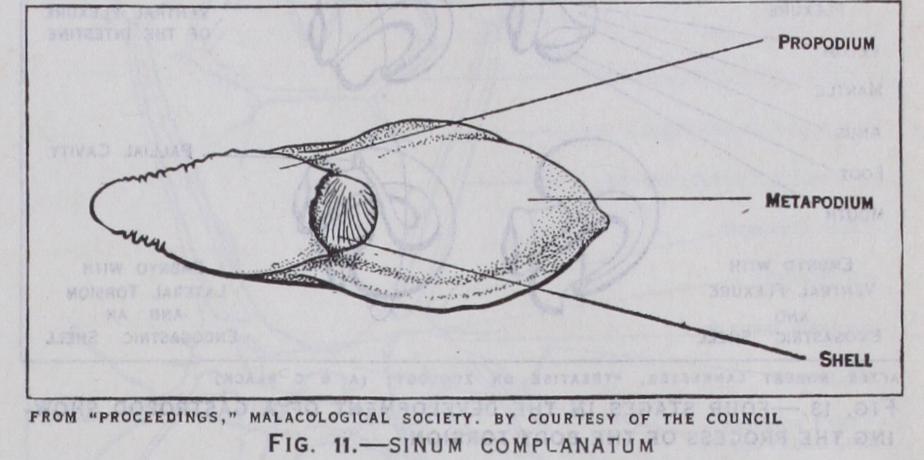

Notable modifications of the foot are seen in marine forms which dig in sand (Natica, Bullomorpha). These gastropods have the foot transformed into a "digging-shield" shaped like a snow plough. In heteropods and "pteropods," it is modified for use in swimming.

On the posterior dorsal surface of the foot there is in nearly adult Streptoneura a solid plate, the operculum. When the ani mal withdraws itself into its shell, this plate by reason of its position and shape remains applied to the aperture of the shell which it closes like a lid. The operculum is absent in nearly all the Euthyneura, but certain terrestrial forms such as the Helici dae secrete a glutinous or calcareous plate over the mouth of the shell when they estivate or hibernate.

The foot often exhibits along its sides a ridge (epipodium) which extends from the head to the posterior extremity. The epipodium is well-developed in the Rhipid oglossa and often bears appendages and sense-organs. It has been assumed to have a common origin with the funnel of the Cephalopoda. The head and foot are joined to the visceral mass by a narrow and highly mobile "neck." The animal is attached to the shell by the strong colu mellar muscle, and by the contraction of the latter the animal can withdraw itself into the shell. This muscle is inserted into the columella or axial pillar of the shell (cf. fig. 9).

The disposition of the chief external parts having thus been sketched, it will now be convenient to describe how the characteristic gastropod asymmetry is at tained. Some details of the internal or ganization are given below; but it is necessary at this stage to recall the preliminary statement that, while some primitive forms are symmetrically organized, the main parts of the visceral complex (gills, kidneys, etc.) being paired, in most gastropods the organs of the right hand side are atrophied or absent in the adult, and that in the Streptoneura the visceral commissure is twisted into a figure-of-eight. In addition, the spiral winding of the shell and visceral mass has to be accounted for.

Before considering how and in what circumstances this highly characteristic organization was developed in the course of gastro pod evolution, it will be best to describe the main organization and metamorphosis of a gastropod larva.

As will be seen in the section on embryology, the larva is sym metrical in the early stages of development, the mouth and the anus lying at opposite ends of the body. At a stage which more or less corresponds with the appearance of the shell, the anus shifts downwards and forwards and ultimately comes to lie below and near the mouth. At this stage the mantle cavity is seen as a small space surrounding the anus. Such coiling as the shell may show at this stage is "exogastric," i.e., the coils are situated above the head and away from the foot. Soon, however, the anus, the mantle cavity and the adjacent parts rotate upwards and come to lie above the head and to the right of the latter. The coils of the shell at the same time roll downwards and assume an "endogas tric" position, i.e., they lie over the foot and away from the head. It will be seen that there are two movements involved in this reorganization of the larval symmetry, viz., the ventral flexure of the intestine and the torsion or rotation of the pallial complex up the right side of the body. Though these two changes may be merged into one in individual development they must be care fully distinguished. The ventral flexure is found in the gastro poda, Cephalopoda, Scaphopoda, and Lamellibranchia ; torsion is found in the gastropoda alone.

If processes of this kind, which occur in the course of ual development, may be taken to epitomize events which happened during the evolutionary history of the race, then it is to be inferred that phosis is a summary of changes which took place in gastropod evolution. Many theories have been put forward to account for these processes. They agree in attributing great importance to the influence of the spiral shell and the acquisition of a flat and elongate sole. If it is true that the gastropoda are descended from animals with a simple cap-like shell and a relatively small foot, then it seems likely that, as the shell acquired a tubular shape, it became necessary to bring the originally posterior anus and associated organs into a position in which they would not be covered in by the growing shell. Hence the flexure of the intestine, the result of which was to bring the anus near the head. But it plainly could not persist in this position, as the elongation of the foot would tend to drive it backwards. Its rotation up the side of the body, until it came to lie above and to the right of the head, brought it into the most convenient position. It is also likely that the change in the spire of the shell from an exogastric to an endogastric tion may have influenced the torsional process. Naef assumes that the animals which gave rise to the primitive gastropods were swimming forms. In such a mode of life the exogastric spire would be no inconvenience. But with the advent of a creeping habit the heavy, forwardly directed shell could no longer maintain its position and would fall on one side. This ment of the shell would almost inevitably affect the position of the pallial complex. The position ultimately taken up by the latter may be explained either as directly due to the displace ment of the shell or as an adaptation that placed the pallial complex in a less cramped and restricted situation. It is quite uncertain whether the rotation of the shell or growth of the foot was most influential in bringing about torsion. It is likely that both contributed.

The foregoing account must not be taken as a description of actual events but of the factors which are likely to have been concerned in producing flexure and torsion. The spiral winding of the shell and the torsion of the viscera are to be carefully dis tinguished, as they are probably not causally connected. The main process of torsion, at least in ontogeny, takes place before the spiral winding of the shell and visceral mass is manifest. The cause of the actual asymmetry of the internal organs is not entirely clear. The twisting of the visceral commissure may be due to the effect of the torsion ; but the atrophy and reduction of the originally left hand organs is not at first sight referable to the latter. They have been explained as due to the pressure of the shell after it has assumed the endogastric position.

In the Euthyneura the process outlined above tends to be reversed (detorsion). The vis ceral commissure is untwisted, the anus and pallial complex in cer tain forms are carried to the posterior end of the body, and with the loss of the shell a sec ondary symmetry may be at tained. Naef wishes to distinguish between the detorsion of the Pulmonata and that of the Opis thobranchia and to refer them to different causes.

The Alimentary System.— The mouth is situated at the anterior end of the head, which is usually snout-like and bent somewhat downwards. In many of the Streptoneura the mouth is at the end of a proboscis which can be thrust out or withdrawn into the cavity of the head. A proboscis is found in certain Taenioglossa (e.g., Natica, Copulus), the Rachiglossa and sundry opisthobranchs, notably the Gymnosomata, and is usually asso ciated with a carnivorous diet.

The mouth leads into the buccal, or pharyngeal cavity, which is furnished in most cases with solid cuticular mandibles and a tongue-like organ, the radula, which is beset with numerous rows of teeth and is used for rasping the food. The mandibles are absent in certain forms—Toxoglossa, Helicinidae, hetero pods—and are rudimentary in the Rachiglossa. It is uncertain whether the mandibles are to be correlated with a vegetarian diet, but they are without doubt absent or rudimentary in many car nivorous forms. The radula is secreted in a pharyngeal coecum, and is a narrow, ribbon-like organ consisting of a basal membrane supporting a number of rows of teeth usually arranged in two symmetrical sets, one on each side of a median tooth. The num ber, arrangement, and shape of the teeth are very characteristic and are of great systematic value as they serve to distinguish not only the larger groups (sub-classes, orders, etc.) but also genera and species. The range in the number of teeth is very wide.

In some of the Eolids there are only 16 rows each with a single tooth. In Umbra culum, on the other hand, there may be as many as 750,000 teeth.

On either side of the radula are two salivary glands which usually secrete only mucus, though in sundry carnivorous gen era they contain an acid which dissolves the hard parts of animals which serve as food.

The oesophagus is generally long and tubular and its inner wall is thrown into numerous folds. In the Stenoglossa it bears a characteristic gland, which in Conks and other Toxoglossa con stitutes the "poison gland." The portion of the oesophagus ad jacent to the stomach is sometimes enlarged to form a muscular "gizzard," the walls of which are lined with teeth or plates.

The stomach is usually thin-walled, but it is lined with a hard cuticle in many genera. It has no digestive function other than that of containing food which is being digested. Digestion is effected by the liver and (when present) the crystalline style. The liver is usually a bilobed organ, the left lobe being larger than the right in most cases. It secretes a digestive ferment which is poured into the stomach by two ducts, and it also has absorp tive and excretory functions. The crystalline style is a rod shaped structure usually of tough, gelatinous consistency, which is either lodged in a special pyloric coecum or lies free in the proximal part of the intestine. It is composed of globulin and, according to Mackintosh, contains an amylolytic enzyme.

The intestine is long or short, according as the animal is her bivorous (e.g., Patella) or carnivorous (e.g., Pterocera). Its inner wall is raised into a prominent ridge, the typhlosole. The anus usually lies on the right side of the body adjacent to the head ; but in "detorted" forms it is at the posterior extremity of the body.

Circulatory and Respira

tory Organs.—The blood is usu ally colourless and contains amoe bocytes. Haemoglobin is found in the blood of certain species of Planorbis and haemocyanin in a few genera. The lymphatic tissue is either diffuse or concen trated in a special gland (e.g., in certain Opisthobranchia). The heart is always dorsal in position. It is usually in front of the visceral mass, but it becomes posteriorly situated in some of the Opisthobranchia as the result of complete detorsion and the re acquisition of bilateral symmetry. In the Rhipidoglossa (with few exceptions) it consists of a ventricle and two auricles, but even in this group the left auricle is larger than the right. In Fissurella alone are the auricles equal in size. In all other gastro poda there is only one auricle, the left.There is a well-developed arterial system in nearly all gastro poda. The venous blood, on the other hand, is carried to the gills through a system of irregular cavities that extends between and among the various organs. From these it is carried to the gills either directly or through the kidney by means of a "portal" system.

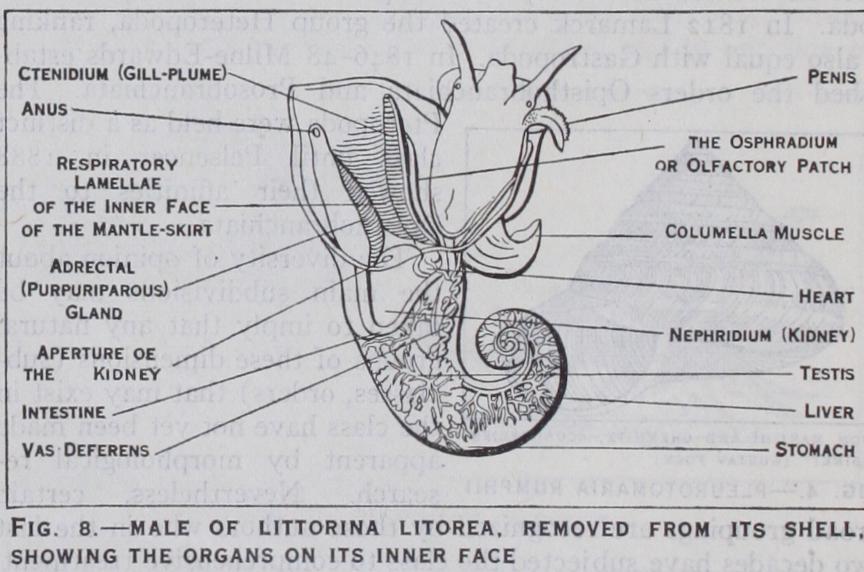

Respiration is aquatic in the majority of gastropoda and is usually carried out by gills. The latter are expansions of the under side of the mantle and are primitively feather-like struc tures (ctenidia), a number of delicate vascularized filaments be ing borne on each side of a central stem in which are situated two blood-vessels. By one of these the venous blood is carried to the filaments for oxygenation, after which it passes in the other to the heart.

In more specialized gastropoda the gills become comb-like owing to the suppression of the filaments of one side. There are two gills in the more primitive Rhipidoglossa (Pleurotomaria, Fissur ella and Haliotis). In all other gill-bearing forms the topograph ically left gill alone persists.

Although the respiration of the gastropoda is primitively aquatic and is of this nature in the larger part of the class, several impor tant groups have become terres trial in their habitat and either breathe air or are amphibious.

The consequent modifications of the respiratory apparatus are manifold and even among marine forms the normal gills are liable to curious and rather inexplicable modification. The mantle in fact retains to a surprising degree a generalized capacity for dis charging the respiratory function and for putting forth respiratory organs not homologous with true gills. Thus respiration from the surface of the mantle may coexist with ctenidial respiration (Heteropoda, Acmaea) or a true gill may be found along with secondarily developed respiratory outgrowths (Scurria) . The true gill may disappear and be replaced by numerous secondary out growths (Patella) or there may be no special branchial organs at all, and respiration is effected by the surface of the mantle (Lepeta) .

In the gastropoda which have taken to living on land, the whole mantle-cavity is transformed into a lung. Among certain marine and freshwater Streptoneura there are sundry genera (Littorina, Cerithium, Hypsobia) which are accustomed to live out of the water for long periods. Their mantle cavity has an incipient lung like structure, though the gill is still more or less normally devel oped. The fully developed lung is formed by the adhesion of the mantle edge to the "neck" and the consequent closure of the man tle cavity which remains in com munication with the outer air by a small aperture (the pneumo stome). The pulmonate condition has been acquired separately by at least three groups of gastro poda, viz., the Helicinidae among the Rhipidoglossa, the Cyclosto matidae among the Taenioglossa and the Pulmonata among the Euthyneura.

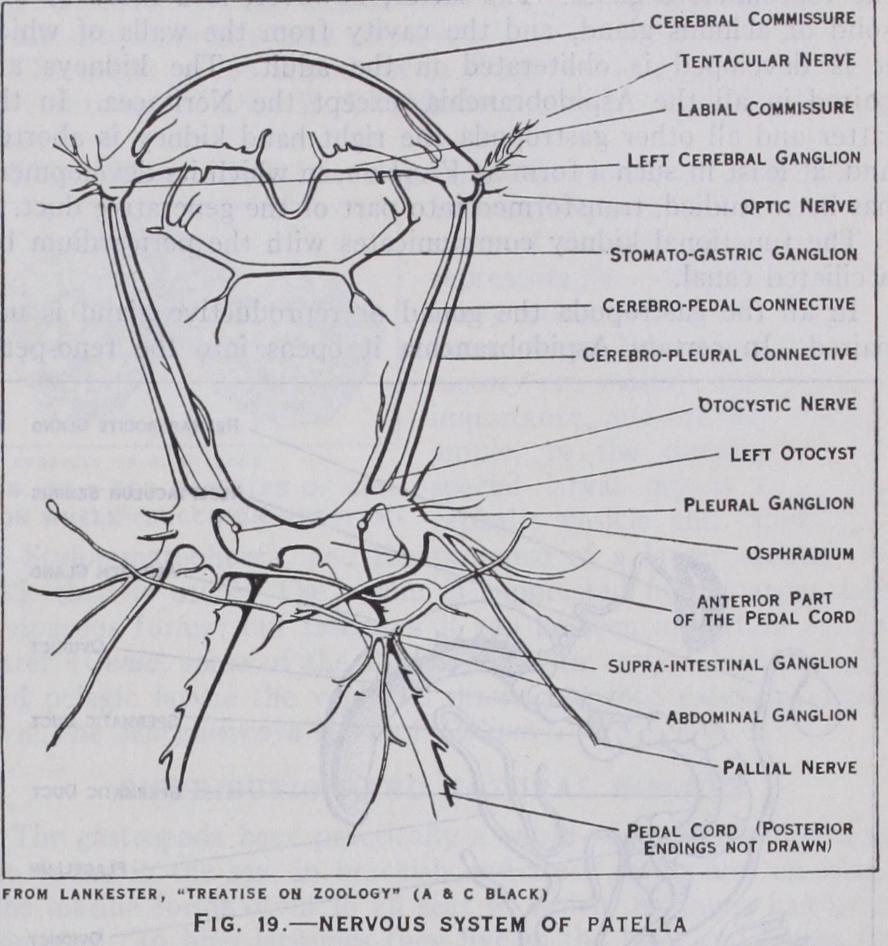

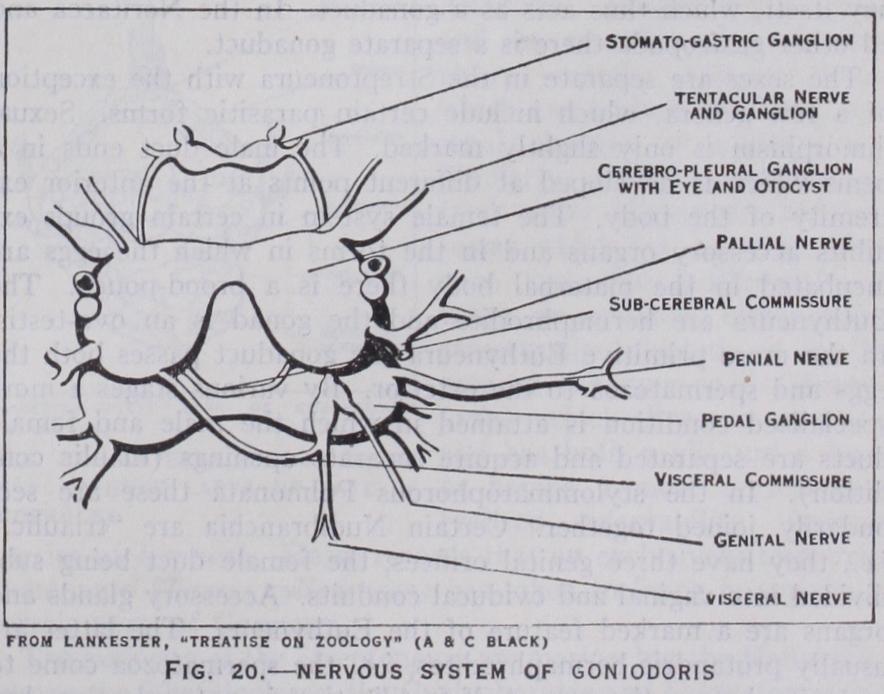

The Nervous System.—Ex cept in certain parasitic forms the nervous system is well devel oped. It consists of nerve cords, ganglia connected by commis sures and sense organs. The vari ous ganglionic centres and com missures are those found in other molluscs, viz., cerebral, pleural, pedal, visceral and stomatogas tric. Archaic traits are seen in certain Rhipidoglossa, e.g., the slight differentiation of some of the ganglia in Pleurotomaria.

The more primitive gastropoda are distinguished by the diffuse ness of the system, the various ganglia being separated by fairly long commissures. In certain Taenioglossa and the Stenoglossa, among the Streptoneura, and in the Nudibranchia and Pul monata, the commissures are shortened and the ganglia are con centrated in the head. The visceral commissure is twisted into a figure-of-eight in all the Streptoneura and in a few Tectibranchia (Acteon, Bulls, etc.), but in nearly all the Euthyneura it is untwisted.

The sense organs are eyes, otocysts (organs of balance) and rhinophores or osphradia (olfactory organs). In addition to these organs there are special sensory tracts in various regions of the body which have a less defined and less complex structure.

The eyes are found upon or at the base of the tentacles of the head. They are primitively cup-like invaginations with a pigment ed retinal layer, which is thus exposed to the sea water. Such simply constructed eyes are seen in the limpets (Docoglossa). In other Rhipidoglossa the aperture of the cup is still open, though it is very small, and a lens is secreted. In most other gastropoda the aperture is closed by the approximation and fusion of the edges of the original aperture, and a double cornea is formed. The olfactory function is discharged by the osphradia in nearly all aquatic gastropoda. There are two of these organs in such Aspidobranchia as have two gills and in the Docoglossa, and a single osphradium in the rest of the class. They are situated in the mantle-cavity near the gills or gill and are essentially organs for testing the respiratory quality of the water. In structure they may be described as ridges of ciliated epithelium. In terrestrial gastropods the osphradia are replaced by rhinophores which are borne on the tentacles. The organs of balance (otocysts and statocysts) are hollow vesicles lined with ciliated epithelium in which sensory cells occur. They contain hard concretions (otoliths) which impinge on ciliated endings of epithelium and transmit stimuli to the sensory cells. Otocysts are found in the foot in creeping forms ; but are sometimes nearer the cerebral ganglia.

Coelom, Renal and Reproductive Systems.

The coelom is represented by the pericardium, kidneys and, theoretically, by the reproductive gland. The latter, however, is a more or less solid or acinous gland, and the cavity from the walls of which it is developed is obliterated in the adult. The kidneys are paired in all the Aspidobranchia, except the Neritacea. In the latter and all other gastropoda the right hand kidney is aborted and, at least in such a form as Vivipara, in which its development has been studied, transformed into part of the generative duct.The functional kidney communicates with the pericardium by a ciliated canal.

In all the gastropoda the gonad or reproductive gland is un paired. In certain Aspidobranchia it opens into the reno-peri cardial canal, as in some of the Lamellibranchia, or into the kid ney itself, which thus acts as a gonaduct. In the Neritacea and all other gastropoda there is a separate gonaduct.

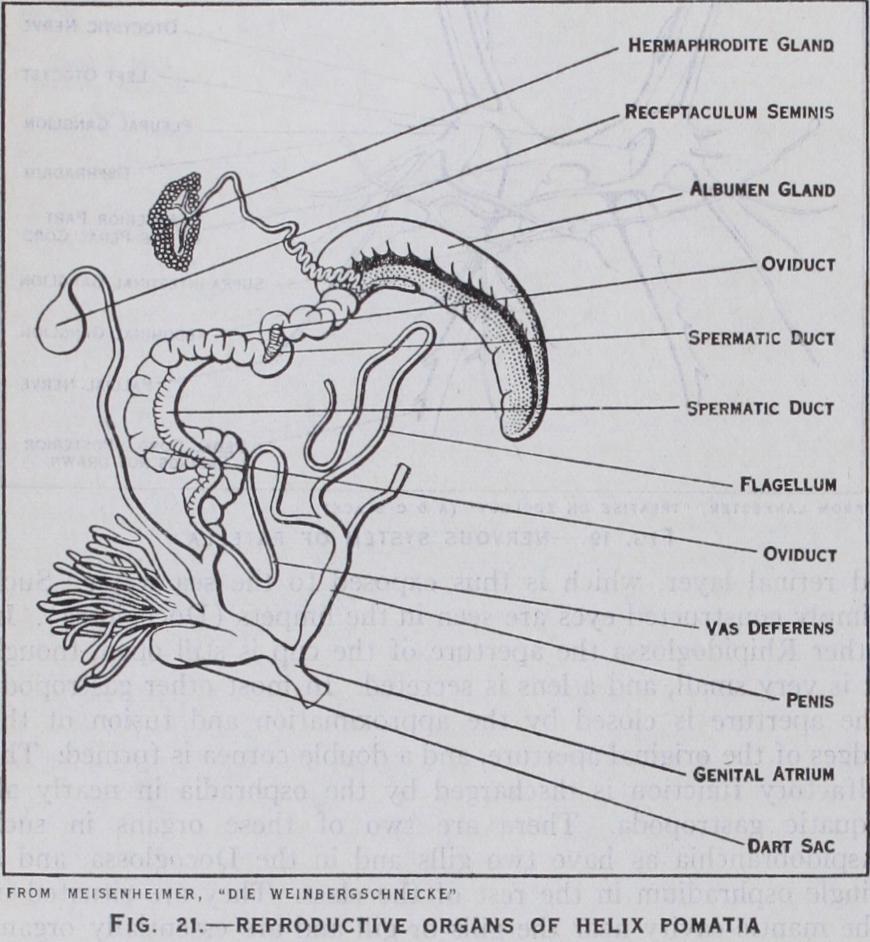

The sexes are separate in the Streptoneura with the exception of a few genera, which include certain parasitic forms. Sexual dimorphism is only slightly marked. The male duct ends in a penis which is developed at different points at the anterior ex tremity of the body. The female system in certain groups ex hibits accessory organs and in the forms in which the eggs are incubated in the maternal body there is a brood-pouch. The Euthyneura are hermaphrodite and the gonad is an ovo-testis. In the more primitive Euthyneura the gonaduct passes both the eggs and spermatozoa to the exterior. By various stages a more specialized condition is attained in which the male and female ducts are separated and acquire separate openings (diaulic con dition). In the stylommatophorous Pulmonata these are sec ondarily joined together. Certain Nudibranchia are "triaulic," i.e., they have three genital orifices, the female duct being sub divided into vaginal and oviducal conduits. Accessory glands and organs are a marked feature of the Euthyneura. The latter are usually protandric hermaphrodites, i.e., the spermatozoa come to maturity before the ova. Self-fertilization is not unknown, but usually one individual is fertilized by another. It is worth noting that in one or two cases (Patella, Crepidula) among the Strep toneura a change of sex may take place in the same individual and that in sexually differentiated forms hermaphrodite individ uals are occasionally found (Acmaea, Lottia, Ampullaria, Conus). Parthogenesis (development of the ovum without fertilization) is known in one case (Paludestrina jenkinsi).

Breeding Habits, Oviposition, Etc.

The breeding habits of very many gastropoda are unknown and in few cases is the life history from fertilization onwards known in all its details.In certain primitive Streptoneura the eggs are fertilized ex ternally in the sea water; but in most members of the class the male has a penis and fertilization is internal. The courtship of certain land snails has been carefully stud ied, and as an example the complex be haviour of the Roman snail (Helix poma tie) which has been described by Meisen heimer should be studied. In many land snails courtship is usually accompanied by some act of violent stimulation, usually by means of a calcareous pointed rod (the dart) secreted in part of the male repro ductive system.

The eggs are usually laid soon after fer tilization. They are either deposited singly (Haliotis, Gibbula, Paludestrina) or in clusters which sometimes form an elabo rate "nidus." This may be a simple gelati nous mass (Limnea) or a ribbon (certain Opisthobranchia) or a series of horny cap sules each containing many eggs may be accumulated in a mass or strung together as a sort of "roulette" (Rachiglossa). The capsules in the latter are formed by a spe cial gland of the foot, a lengthy operation lasting many days. Certain Streptoneura attach their eggs to the external surface of their own shells or those of their neigh bours (Paludestrina, some species of Theo doxis, Capulus) or deposit them inside the shell (V ermetus) . Ianthina secretes a gelatinous raft on the under surface of which the eggs are suspended. Most of the land snails lay their eggs in holes underground. These are enclosed in a gelatinous envelope (Limax) or in a calcified shell (Helicidae). Certain Bulimulids lay eggs with calcified shells 2-3cm. long, resembling those of birds.

The habit of carrying the eggs on the shell may be perhaps considered as a prelude to more definite and protracted care of the young. Vermetus, as has been pointed out, carries the eggs inside the aperture of the shell and certain species of Li bera (a pulmonate) places its eggs in the umbilicus of the shell and covers them over with a se cretion rather like an epiphragm. There are, however, a good many viviparous or ovovivipa rous gastropods, Vivipari, Typlio bia, a certain species of Melanie, and sundry pulmonates incu bate their eggs in the terminal part of the oviduct (uterus), while in Tanganyicia and Me lanie episcopalis there is a special brood-pouch which is separate from the oviduct.

The number of eggs varies ac cording to the mode of life and oviposition. Purpura lapillus (the dog whelk) deposits up to 150,000 eggs in its capsules and sundry species of Doris lay as many as 600,000. It should be noted that in those Rachiglossa which form capsules containing many eggs some of the latter are devoured by those embryos which emerge first. Interuterine cannibalism has been recorded in the pulmonate Limicolaria. The Pulmonata do not as a rule lay as many eggs as the Streptoneura and Opisthobranchia. Helix asperse deposits up to I oo.

Developmen.

Although the gastropoda display very con siderable variation in the adult form, the cleavage of the eggs is more or less the same in all the cases in which it has been studied. Such variation as may have been observed is due to variation in the amount of yolk.In all gastropoda which have been so far studied cleavage is total and of the type known as spiral. The egg divides into two and then into four cells which are either equal in size (Patella) or approximately equal. A third division then cuts off four small cells (micromeres) from the four original cells (macromeres). There are now eight cells con sisting of a "quartette" of micro meres and the four larger macro meres. The next division gives rise to 16 cells, viz., four more micromeres, which are given off from the macromeres (second quartette) and the products of the sub-division of the first quar tette of micromeres. Division proceeds in this way until a cap of numerous micromeres is found lying on top of the four macro meres. In Patella, in which the development is well known, the embryo is at the 32-cell stage radially symmetrical. On the at tainment of the 64-cell stage this is replaced by bilateral sym metry.

Owing to certain features of the mode of cleavage, it is possible to trace the "lineage" (developmental history) of individual organs back to individual cells or quartettes produced by very early cleav age. This type of research has been a very fruitful source of embryological knowledge, but can only be summarily mentioned here. The micromeres give rise to the ectoderm and its deriva tives, the macromeres to endoderm and mesoderm. In Patella gastrulation is by epibole (overgrowth) of the macromeres by the micromeres. At the end of 24 hours the embryo, which up till now has been contained in an egg-membrane, escapes and be gins its free-swimming period as a trochophore larva. It is more or less spherical and surrounded by a girdle of long cilia (the prototroch) developed from spe cial trochoblasts.

The gut is now developed, the endodermal cells dividing to form the stomach and the mouth and anus arising as ectodermal invaginations. Dorsally, a thick ened plate of cells gives rise to the shell-gland, the foot is indi cated by two slight prominences on either side of the mid-ventral line, and the mesoderm bands are now formed.

Enlargement of the prototroch to form the velum and the growth of the foot characterize the veli ger stage. The metamorphosis of the larva has already been de scribed.

The detailed development of the individual organs is not very well known in marine molluscs. We owe the bulk of our knowl edge on this subject to the studies of V. Erlanger, Drummond and Tonniges on Vivipara, the pond snail (originally called Paludina) . The ganglia of the nervous system arise as thicken ings of the ectoderm which subsequently become joined together by connectives. The otocysts and eyes are ectodermal invagina tions. The pericardium originates as a hollow in the mesoderm and the heart is first seen as a vesicle projecting down from the dorsal wall of the pericardium. The kidneys are tubular exten sions of the pericardial cavity ; they are joined by ectodermal in vaginations which constitute the ureters. The gill appears as a series of folds in the wall of the mantle cavity. The germ cells seem in the first instance to be budded off the pericardial wall and subsequently form a spherical vesicle, the gonad. The kidney of the originally left-hand side forms part of the genital duct.

The origin of the mesoderm in Vivipara has been the subject of controversy. (See E. W. MacBride, Text Book of Embry ology.) The account of larval development and organogeny given above is founded very largely upon the study of Vivipara, but it probably represents the course of events in many other gastropods. Depar tures from this developmental history are mainly of secondary importance, and are due, for ex ample, to the development of special larval organs (e.g., the cephalic vesicle and "podocyst" of Stylommatophora), and the presence of a larger amount of yolk than is usual. The velum is suppressed in oviparous and viviparous forms ; but traces of it can be seen in certain of the latter (Cenia, some of the Pulmonata). In certain highly modi fied pelagic larvae the velum is drawn out into extensive lobes (e.g., the Macgillivraya larva of Dolium).

The gastropoda have practically a world-wide distribution and are found in the sea, in brackish and fresh water and on land. The marine forms occur in all seas of which the fauna has been examined. In high latitudes they live in the bays and fjords of the Antarctic continent (e.g., in the Ross sea, 77°S.) and off the northern coasts of Greenland and Franz Josef Land. Exactly how far north they occur is uncertain; but in all probability they range right across the north Polar sea. The exclusively marine forms are limited in their distribution by salinity and other environ mental factors. But, though it is true that the life-zones that prevent them from invading fresh water and land interpose a strict barrier to their invasion of those habitats, there are cer tain groups which are intermediate between truly marine forms and those which habitually live in fresh water and on land. The common periwinkle (Littorina litorea) can tolerate very pro tracted exposure to air (see