Glacier

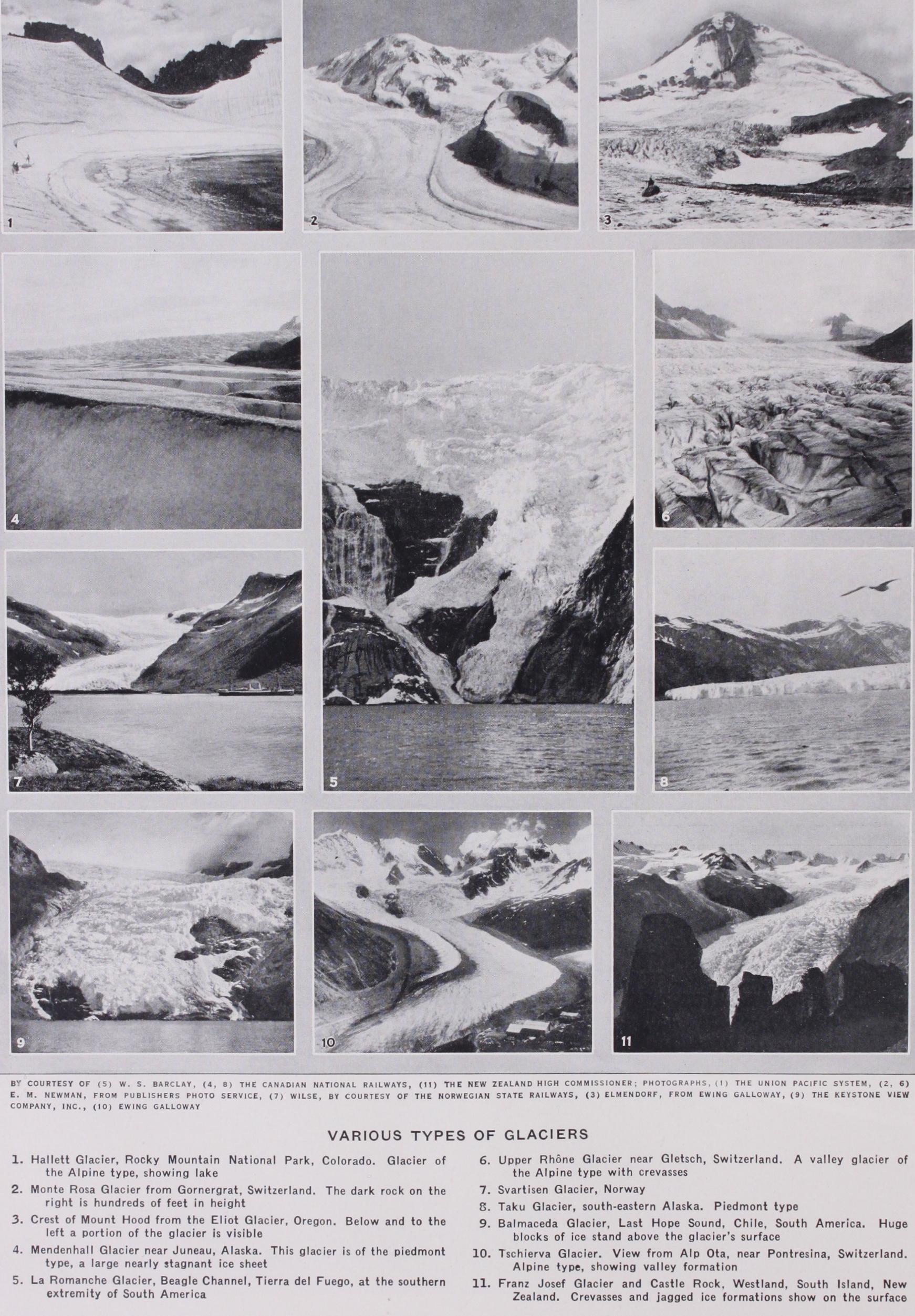

GLACIER, a mass of compacted ice originating in a snow field (French, glace, ice, Lat. glacies) . Glaciers occur in those portions of the globe where the rate of precipitation is greater than the rate of melting of the snow. These conditions are ful filled in high mountain tracts and in the Polar regions. The lower limit of a snow-field, above which the snow lies throughout the whole of the year, is known as the snow-line. The altitude of the snow-line, changes locally as well as at different latitudes, vary ing from r S,000 to i 8,000 ft. in the tropics to sea level in the Polar regions. The main features of the type of glaciation of a region depend upon the topography, the geographical position and the elevation above sea level. Apart from the Polar ice-sheets, four distinct types of glaciation have been recognized :—the Al pine, Piedmont, Spitzbergen and Greenland types, but as many of the fundamental facts were first studied in regions where the Alpine type occurs, this will be described first.

Alpine Types.

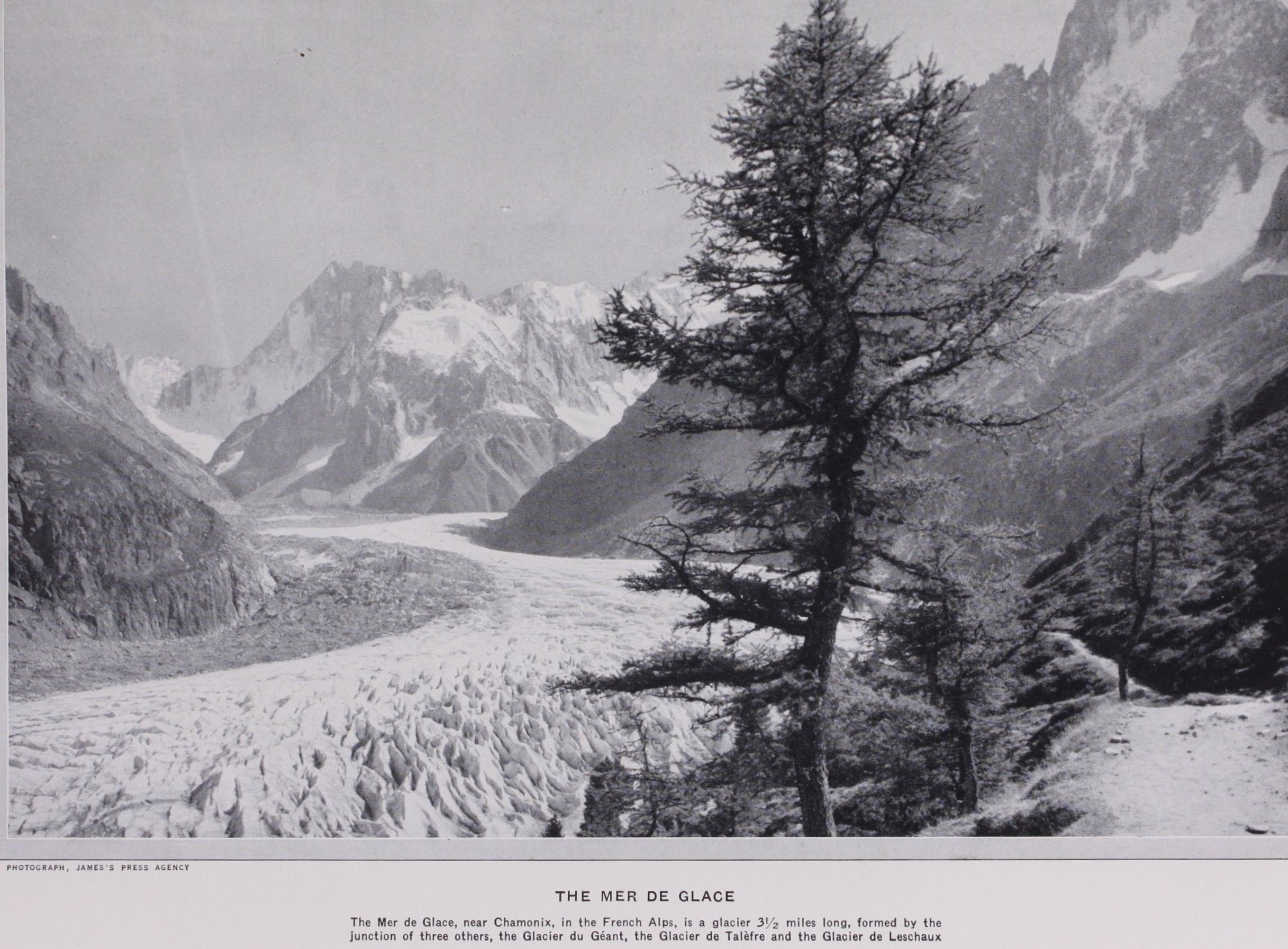

In mountain regions snow accumulates on gentle slopes, in high mountain valleys, in hollows and depres sions and on the summits of dome-like peaks. Owing to the weight of accumulated snow, the lower layers become compacted together into dense clear ice with a granular structure through out. This is known as neve or fern. The ice thus formed is more or less stratified as the result of successive falls of snow and of melting between falls, and by the accumulation, between suc cessive falls, of films of dust from the air or from the snow which has melted. Wind causes the drifting of the snow, produces a rippled surface on the neve and carries loose snow to lower altitudes. The neve is comparatively easy to cross on foot; very little debris cumbers its surface but concealed crevasses (cracks in the ice) are a source of danger. The most important crevasse in this part is the bergsclarund which has the form of a great symmetrical arc at the head of the neve. It lies but a short distance from the exposed rock surface and the rock wall is exposed to disintegration by frost action, and the debris thus formed drops to the bottom of the crevasse. Frost action also affects all exposed rocks in these high mountain tracts, pro ducing sharp pointed pinnacles (aiguilles), aretes and precipitous crags, snow capped peaks being protected from frost action. The disintegrated rock falls downward and much of it finally comes to rest upon the edge of the neve where it forms a moraine.Glaciers creep down the mountain side. The greatest move ment naturally takes place in the summer when the average tem perature is above freezing point. The rate of movement also depends upon the mass of snow and ice, the slope and smooth ness of the valley floor and the slope of the upper surface of the ice. The rate and direction of movement can be determined by driving stakes into the ice which it is found does not move as one block but yields under the pressure of its own weight by cracking and regelation and moves slowly. The movement can be corn pared to that of a river, the greatest rates being in the centre, the upper layers and in restricted parts of its channel. Because of its higher rigidity, however, shearing of one mass upon another takes place producing foliation within the mass.

The character of the ice changes as it passes down to lower altitudes and at a point where in summer the melting is in excess of the precipitation, the granular ice appears beneath the snow. This point is taken as the lower limit of the neve and below it the valley glacier commences. It is known as the firn-line but it does not necessarily coincide in altitude with the snow-line on adjoining mountains. Below the firn-line, boulders and other debris occur on the surface of the ice. Some of the boulders sink to the bottom but flat varieties do not sink, they protect the ice beneath them from the rays of the sun, so that they remain perched (as ice-tables) on a column of ice as the surrounding ice is melted. Dust and small particles of rock absorb heat from the sun's rays quicker than does ice and therefore they melt the ice beneath them and sink into shallow pits known as dust wells, the action ceasing when the rays can no longer reach them. The moraines increase in size by the addition of material as they pass to lower altitudes. At the confluence of the main glacier with a tributary glacier, the two adjacent lateral moraines meet and pass into the middle of the lower combined glacier producing a median moraine. The lower reaches of a valley glacier may con tain several median moraines. Ground moraines are formed by attrition along the bed of a glacier and they are augmented by debris falling down crevasses. At the lower end of a glacier the melting ice dumps a large portion of its rock burden in the form of mounds, generally crescent-shaped, across the valley producing a terminal moraine. (See MORAINE.) Crevasses are more obvious in the valley glacier than in the neve. They are due to strain set up in the glacier by movement over an uneven surface, or round sharp bends or by differential movement due to other causes. They may be transverse or longi tudinal and may be covered by fresh snow thus producing ice bridges across them. When a glacier passes over a very steep slope the crevasses open wide and produce wedges and pinnacles of ice known as seracs. Frequently the slope may be so steep that the glacier breaks completely along the crevasses and the masses of ice fall to lower levels, where they are moulded again into a solid mass as a reconstructed or recemented glacier. Gla ciers in hanging valleys and on cliff faces, which end in ice-falls are known as glacierets, hanging glaciers or cliff glaciers. These names are also applied to accumulations of neve which are not large enough to produce a valley glacier. Water from surface melting and water which flows on to the glacier from the sur rounding rocks forms lakes or surface streams on the glacier. Such lakes are not of a permanent character, the colour of the water in them is clear blue and they may lie partly upon the ice and partly upon the solid rock. Lakes frequently occur at the confluence of two surface streams. In the majority of cases surface water ultimately finds its way down a crevasse and so are initiated en-glacial and sub-glacial streams. These streams are laden with sediment. Some surface streams disappear down a moulin, which is a cylindrical hole through the ice, the posi tion of which is often fairly permanent and in which the stream sets up a swirling motion so that it bores out a deep pot-hole, known as a giant's kettle (q.v.) in the rock beneath.

The lower end of a valley glacier may advance or retreat. This is regulated by a variety of factors, such as the amount of snow which falls in the catchment area, the rate of movement, and the rate of melting. Observations have been carried out for a number of years on various Alpine and other glaciers in order to obtain accurate information relative to the movement and at tempts have been made to ascertain the relation that it bears to variations in meteorological conditions. It appears that in a period of between 35 and 4o years many glaciers pass through a cycle of advancing and retreating.

Glaciers which extend well down below the snow-line may affect to a considerable extent the drainage of the surrounding country. In such cases tributary streams may be dammed back to form lakes, e.g., Lake Marjelen, and the level of the water may be high enough to cause the effluent to escape over a low lateral col, thus forming an overflow channel, the level of which may ultimately be lowered to permit the draining of the lake and so divert the stream. There is clear evidence of the exist ence of such lakes during and at the close of the Great Ice Age, and the effects of them are seen in the occurrence of overflow channels, lake terraces, permanently modified drainage and in hills of sands and gravels representing lacustrine deltas.

A large part of the morainic material carried by a glacier is dumped at its lower end, forming a terminal moraine. The streams which emerge are heavily laden with sediment, much of which is quickly unloaded forming debris strewn valleys and outwash plains or frontal aprons. Such deposits are rudely strati fied and among them large depressions known as kettles some times occur and these probably mark the sites of large blocks of ice enclosed for a time in the debris. Sands and gravels from the effluent streams are deposited in the rear of the terminal moraines and form rounded mounds, elongated parallel to the direction of the valley. They are known as drumlins. Similar ridges transverse to the valley are termed kames. Drumlins and kames are more frequently associated with ice-sheets than valley glaciers, as also are eskers, osars and serpentine kames, which are long narrow ridges supposed to have been formed by deposi tion directly from en-glacial and sub-glacial streams. The water of effluent streams is dirty grey in colour, due to a large amount of clayey matter suspended in the water in a colloidal state.

Piedmont Type, etc.

The Piedmont type of glaciation is characteristic of Alaska and consists of great valley glaciers meeting to form a large sheet of nearly stagnant ice. The Mala spina glacier, 1,500 sq.m. in extent, is the best example of this type. It has an almost level surface covered with a great amount of debris, sufficient to support dense forests. There is approximate equilibrium between the supply of ice and the loss by melting. The glaciation of Greenland is very different. Here the greater part of the country is covered by an ice-sheet which slopes toward the coast at a very low angle. Valley glaciers occur only in the coastal regions where also rocky peaks, nunataks, project through the ice-sheet. Nunataks vary much in size, are sometimes cov ered by Arctic vegetation and are frequently fringed by crescent shaped moraines, formed by the driving upward of the ground moraine. The latter is not so large as in the Alpine type of gla ciation, for the greater part consists of material torn off from the rock surface beneath the ice-sheet. For long stretches along the coast the ice forms vertical or overhanging cliffs, known as Chinese Wall fronts, their steepness being due to the fact that the lower layers contain more debris and in consequence melt more quickly. The Greenland ice-cap, as well as the great Polar ice caps, sends into the sea a large number of icebergs during the summer. These drift to lower latitudes and gradually disappear by melting. In Spitzbergen there is a central ice-cap on a high plateau, the sides of which are deeply trenched by radial valleys containing valley glaciers. Some of the latter have Chinese Wall fronts when they reach the sea, but others have normal "Alpine" fronts. In the former case the movement of the glacier is comparatively rapid. In some parts of the Himalayas, the glaciers are retreating as they are in North America.Evidences of Past Glaciation.—As already pointed out, the topography and drainage of a region may be considerably modified by glaciation. Glaciers, assisted by frost action upon exposed rock surfaces, are important eroding agents, but authorities are not agreed upon the extent of such erosion. Cirques, with their steep walls and backward-graded floors, aretes and pyramid shaped mountain peaks can all be traced to the eroding action of frost : hanging valleys, U-shaped valleys, truncated spurs and steps in a valley floor to the deepening action of valley glaciers: roche moutonnees, rounded, striated, grooved and polished rock surfaces, and striated and polished erratics to the smoothing ac tion of moving ice : and the scratching power of rocks frozen into the glacier : the occurrence of erratics and perched blocks to the transporting power of moving ice. Giant's kettles, over flow channels and old lake terraces (e.g., the Parallel Roads of Glenroy) are evidences of water action associated with glaciers. Boulder clay is the deposit left behind by a retreating ice sheet. Lateral and terminal moraines, with associated "kettles" are formed by the melting of a valley glacier : drumlins, kames and outwash plains by fluvio-glacial action: eskers, osars and serpen tine kames by deposition by en-glacial and sub-glacial streams. Icebergs breaking away from the Polar ice-sheets transport ma terial for a considerable distance. A large number of the lakes in higher latitudes are of glacial origin. (See LAKE.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Among the older works the following must be menBibliography.-Among the older works the following must be men- tioned: J. Tyndall, The Glaciers of the Alps (1896) ; T. G. Bonney, Ice-W ork, Past and Present (1896) ; H. Hess, Die Gletscher (19o4) ; in addition there are: W. H. Hobbs, Characteristics of existing Glaciers (IQ11) ; W. M. Davis, The Sculpture of Mountains by Glaciers (Scot. Geog. Mag. 1906) ; A. Penck and E. Bruckner, Die Alpen im Eiszeit alter (1909) ; W. B. Wright, The Quarternary Ice Age 0914); A. P. Coleman, Ice Ages (1926) ; the two latter books contain good bibli ographies. In addition mention must be made of the descriptions of the expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic regions within recent years (J. I. P.)