Glass Manufacture

GLASS MANUFACTURE. The term "glass" has two meanings, one used in science only, the other generally. To the chemist and physicist the word glass signifies the special state of matter assumed when a liquid substance is cooled continuously, and, becoming more and more viscous, finally hardens without, at any stage, crystallizing. Glycerine at low temperature, resins, pitch, sealing wax exhibit such characteristics, although the term glass is often confined to transparent materials. Substances in this "under-cooled" state are spoken of as having assumed the glassy or vitreous condition ; they have in general, properties like common glass.

Common glass, which fulfils all the requirements of the scien tific term "glass," is readily recognizable but much less easy to define briefly. It is usual to describe glass (that is, mineral or inor ganic as contrasted with organic glasses) as a hard, brittle, amor phous substance, breaking with a conchoidal (or shell-like) frac ture, usually transparent, but in some cases translucent or opaque, and either colourless or coloured ; produced by the fusion of acidic oxides, or, most frequently, of acidic and basic oxides together, the fused mass being subsequently cooled sufficiently quickly as to prevent the deposition from it of crystalline mate rial in solution. The definition, long as it is, is not perfectly watertight ; because opal glasses are produced by inducing dep osition of small particles, usually crystalline, in the glass on cooling. As an amorphous substance, glass has properties which, unlike those of a crystal, are the same in whatever direction we measure them. For example, glass is equally refractive of light throughout its mass. The definition says that glass is produced by the fusion of some acidic oxide either alone, or usually with some basic oxide. It is, therefore, not one but many substances, the term being employed like the word "metal" in a collective sense. The acidic oxides which find use in glassmaking are silica (sand), boric oxide, oxides of arsenic, oxides of antimony, and phosphoric oxide. The only one which of itself is valuable for producing a commercial glass is silica.

Of basic oxides, those occurring in common use are soda, potash, lime, magnesia, lead oxide, barium oxide, zinc oxide, alumina. These may be described as fundamental constituents and give no colour to the glass. Commonly employed for imparting colour are the oxides of iron (bright green, bluish-green, dark green, brown and even red according to conditions) ; oxides of copper (blues and reds) ; cobalt oxide (blue) ; nickel oxide (purple to brown) ; manganese dioxide (purple to brown) ; chromium oxide (yellowish green) ; uranium oxide (fluorescent green or yellow) ; titanium dioxide (yellow to brown). Tin oxide and zirconia have been used in opal glasses. The actual colour obtained depends on the amount of the colouring oxide, the general composition of the glass and frequently also the temperatures, time of melting, and the furnace atmosphere. Nickel oxide and manganese dioxide both tend, for example, to produce a purple colour in potash glasses, but brown in soda glasses. Combinations of colouring oxides can be used to produce intermediate shades. Substances other than oxides may be added to produce colours, such as cadmium sulphide (yellow), selenium (red), finely divided gold (ruby), silver salts (yellow), carbon (yellow-brown), sulphur (yellow) ; whilst fluorspar, cryolite and bone ash (calcium phos phate) are much more commonly used for making opal glasses than tin oxide or zirconia.

Types of Glass and Glassware.

With such a variety of con stituents to draw upon for glassmaking, it will be understood that the number of glasses available is very great. In practice, the composition chosen depends on (I) the cost (2) the properties of the glass. The properties which have to be considered by the manu facturer include general properties, namely, the ease of melting, since furnaces have their limits of operation, the rate of setting of the glass, which influences the mode of converting it into articles, and the general stability or durability. The special properties aimed at are selected according to the service the glass must give. It may be required for optical purposes, or to be of a special tint ; it may need to be heat resisting, to be electrically insulating or to withstand chemical action; it may be needed to be of special hardness, resistant to scratching; to fulfil certain conditions of mechanical strength or density. Although much re mains to be done, modern investigations have done much to determine the influence which each constituent oxide exercises on the properties of the glass as a whole. Thus, the oxides which make glass specially resistant to the action of water, whether liquid or steam, are silica, zirconia, alumina, zinc oxide, titania, and, under certain conditions, boric oxide; whilst those which render the glass particularly liable to attack are soda and potash. Again, lead oxide increases the refractive index, extends the tem perature range over which the molten or plastic glass can be worked and the glass which contains it is soft for cutting.Some physical properties are related to the chemical compo sition so simply that for many (but not all) glasses a linear or additive relationship holds good. In other words, it is possible within limits to state what contribution each z % of each of the constituents of the glass makes to the numerical value of the property. In a general way this is true of thermal expansion, specific volume (and density), refractive index, specific heat and various mechanical properties.

Other physical properties, such as, viscosity, annealing temper ature, electrical conductivity are not so simply related to the composition, but general relationships have been established. Armed with tables of the specific effects of each oxide, or, in the case of less well-defined relationship, with graphical representa tions, the manufacturer can do much to design a glass composi tion to meet a given specification. Illustrations of such compo sitions are provided in the above table.

Raw Materials and Preparation of the Glass-making Mixture.—The chemical oxides present in the glass are not necessarily introduced in this form in the raw material. Silica, however, is introduced as such, almost invariably as sand. The chief requirements of a sand for glassmaking are high silica con tent and very low iron oxide. For optical glass, best crystal table glass and special illuminating glasses, the iron oxide should be le:3 than 0.02 % ; for common domestic ware and colourless glass bottles, up to 0•05–o•o6% is permissible; for common window glass o• i %. Sands fulfilling the first named requirement are derived from Fontainebleau (France), Hohenbocka and Doren truper (Germany), Ottawa (Illinois), Berkeley Springs (West Virginia) and near Lewistown (Pennsylvania) ; their silica con tent is usually not less than 99.6%. Belgian sand, containing 0.03 o•o6% of iron oxide is exported to various countries including Canada (Montreal) and some of the U.S.A. factories on the Atlan tic and Pacific sea coasts. King's Lynn sand of iron oxide content o.o % is in considerable use in England, together with large im portations of Belgian, Fontainebleau and (rather less) Hohen bocka.

Soda is added to the glassmaking mixture in the form of soda ash (sodium carbonate) and also, in smaller proportions, accord ing to the type of glass to be made, as sodium nitrate, sodium sulphate and borax; potash is added almost always as potassium carbonate and in smaller proportions as potassium nitrate. Lime is added mainly as calcium carbonate (limestone, marble, calc spar, precipitated lime and, rarely, chalk) ; in America fairly frequently as burnt lime or slaked lime, either calcium or dolo mitic lime. Lead oxide is added usually as red lead, sometimes as litharge.

The mixture (or "batch") from the glass is made con tains (a) and (b), and, according to circumstances, one or more of (c), (d) and (e) ; namely (a) fundamental materials (sand, soda ash, red lead, lime, etc.) ; (b) waste glass from a previous melting known as Gullet; (c) oxidizing agents such as sodium or potassium nitrate, or reducing agents such as carbon; (d) de colourizing materials; (e) colouring or opacifying materials.

Waste glass or cullet is invariably added, first for economy, secondly because it assists in the melting. Oxidizing agents are employed under certain special conditions, as, for example, in glasses containing lead oxide in order to prevent reduction of this material to metallic lead by the action of furnace gases; whilst reducing materials are added such as for the purpose of decomposing more rapidly sodium sulphate or saltcake when this forms part of the mixture. Decolourizing agents are em ployed to produce the appearance of colourless glass in cases where otherwise the glass would have a faint green tint due to the presence of iron oxide. The decolourizing agents commonly used in glassmaking are manganese dioxide and nickel oxide (for glass melted in pots) and selenium (for glass melted in tank furnaces), arsenious oxide, in itself a mild decolourizing agent, being an almost invariable accompaniment of one of the fore going decolourizers. Arsenious oxide produces no colour, but each of the others when present in a glass containing no iron oxide, or, in any case, when present in excess, produces a shade of colour, a purple or pink, which within limits covers the green or yellow green due to iron oxide. The amount of iron oxide which can satisfactorily be so covered is not greater than 0.09%.

The raw materials are weighed out ; the decolourizing or colour ing materials being small in quantity are weighed out separately. The chief materials may be mixed either by hand, or mechanically. The waste glass or cullet, in different branches of manufacture, constitutes from 20 to as much as 8o% of the total mixture charged into the furnace.

Melting the Glass.

The batch mixture is melted either in pot or in tank furnaces. In the former the pots or crucibles constitute individual containers of which any number between three and 18 may be set in a single furnace; whilst in the latter the tank serves as one huge receptacle. The pots are built of fire clay, usually by hand, are cylindrical, oval or egg-shape in cross section according to circumstances, and may hold from 3- cwt. to 3o cwt. of glass, the small sizes being used mainly for supplies of coloured glasses. The pots are, if possible, stored for 12 months, slowly drying and "maturing" before use.Open pots are universally used for plate glass melting and in Europe, outside Great Britain, are also used for general purposes. In Great Britain and U.S.A. covered pots are most frequently employed. A 3o cwt.'pot will have a bottom thickness of about 5 in. and walls tapering to about 3 in. at the shoulder, smaller pots having proportionate thicknesses. It is necessary to pre heat them carefully to i,000°–r,3oo° C in a subsidiary furnace (a pot-arch), a process taking 5-12 days, after which they are trans ferred with all speed to the melting furnace, fired hard for 12-36 hours, glazed inside with a little molten glass and then charged with the mixture. When melting is complete, the fluid glass is "refined," that is, made homogeneous and free from bubbles of gas, an abundance of which is evolved during the melting. One method is to plunge the glass with blocks of wood soaked in water, the large steam bubbles sweeping out small gas bubbles. Subsequently the temperature is slowly lowered until the con sistency of the glass is suitable for commencing to work it into articles. The complete melting (melting, refining and cooling off) time depends on the nature of the glass and the furnace tem perature, the normal range of melting temperature being 1,5oo° C. By using medium size pots and high melting tem peratures many factories on the Continent and some in Great Britain are able to melt overnight (about 12 hours) but often 36-48 hours are required.

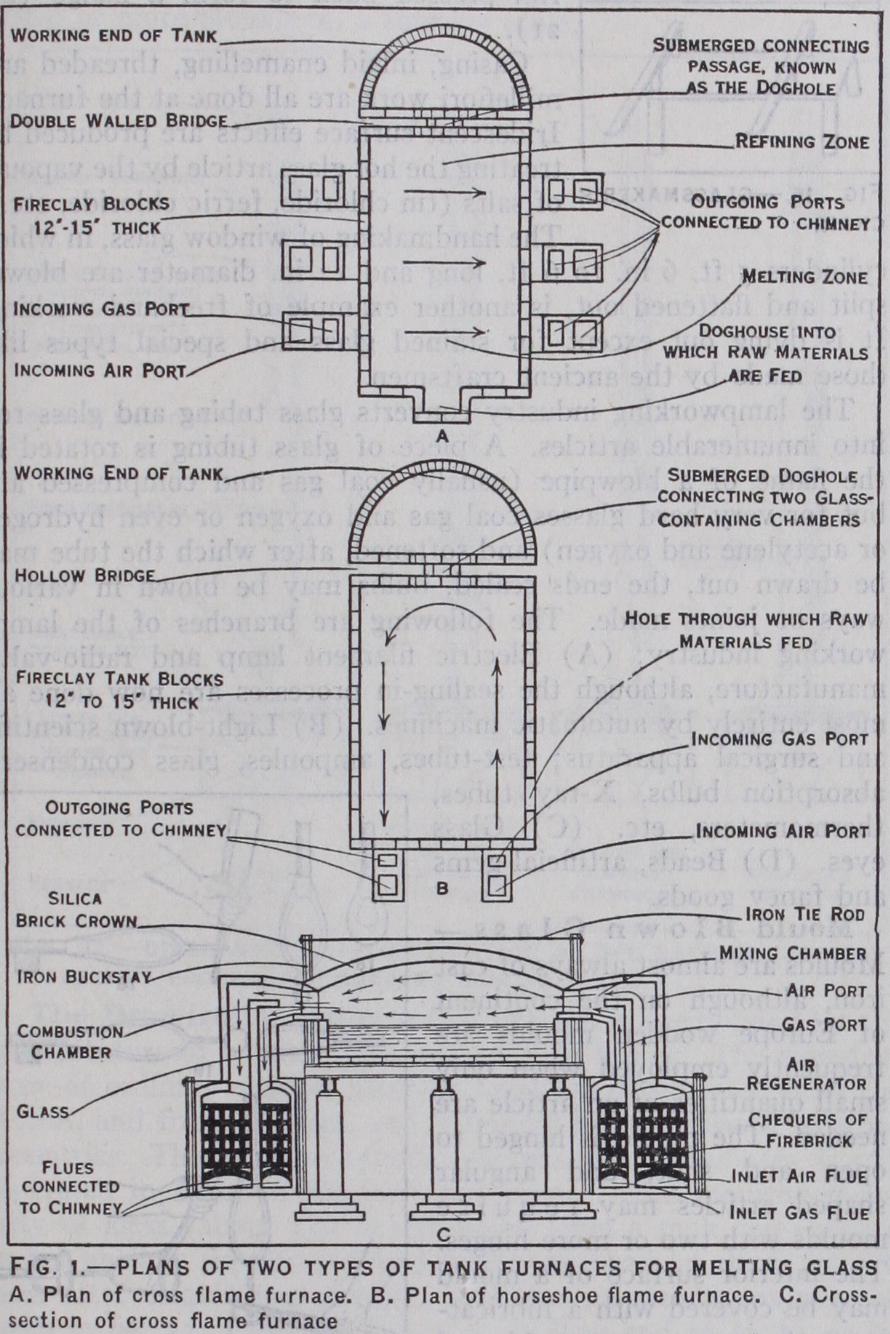

In tank furnaces, charging-in of raw materials at one end, usually through a trough or "dog-house," and removal of glass from the working end are continuous, night and day. Figs. r a, lb and rc illustrate general principles. The heating flames may flow across the furnace Oa and lc) or round the furnace (horse shoe flame) (ib) in furnaces with regenerative preheating of gas and air; or straight down the tank with recuperative preheating of air or in small oil-fired furnaces. Small tanks ("day tanks") without dividing bridge, are sometimes used like pots, being charged with batch which is melted overnight and worked out during the day.

Glass Melting Furnaces.—These vary in design and capacity. Fig. 2 illustrates, in principle, a modern open-pot furnace with re generative preheating of fuel gas and the air for combustion. Producer gas is most frequently used for firing. The gas and the preheated air emerge and burn above the "eye," the flame spreads over the "crown" and the waste gases are drawn down through flues at the sides of the pot and away to the chimney by way of the recuperator channels or through the brick checker work in the care of regenerator chambers.

Glass tank furnaces are constructed, the glass-containing bath of thick (8 in.-15 in.) fireclay blocks for sides and bottom, the upper walls of fireclay bricks and the crown of silica bricks. They average 100-200 tons in deadweight capacity for bottle glass and about Soo for window glass, with actual limits of a few cwt. to i,000 tons for bottle and up to 1,500 tons or more for window glass. Owing to increased efficiency of operation the tendency now (1928) is to diminish tank furnace size. A bottle or domes tic ware glass tank of average capacity will be 4 ft. deep when used for colourless glass and 2 ft. 6 in. to 3 ft. 3 in. for coloured, a window glass tank 5 feet. The working end is usually divided from the melting end by a double-walled bridge, the glass flowing into the working end through a passage (called the "throat" or "dog-hole") near or at the tank bottom. The refining zone lies immediately in front of the bridge and in window glass tanks may be divided from the melting zone by a floating fireclay barrier or bridge.

Conversion of the Glass into Articles.—The glass industry is one of high skill since, unlike many of the metal making indus tries, not only is the glass melted, but it is also converted on the spot into innumerable forms. Factories making table glassware or ornamental hollow-ware usually cut, engrave, etch, enamel or paint the articles made in the "glasshouse" where the melting and shaping occur. The greatest variety of glass articles can be made at factories employing pot furnaces and hand manipulation. Glass tank furnaces, introduced commercially subsequent to 186o, have been displacing pot furnaces rapidly within the past decade and, combined with mechanical methods, have led to specializa tion.

The methods for the conver sion of molten glass into articles include : (I) Free-hand work, (2) blowing in moulds, (3) press ing in moulds, (4) drawing, (5 ) rolling. Examples of each type follow.

Free-hand Work.—We may conveniently classify both gen eral manipulation at the furnace and the lampworking industry under this heading. The for mer is the oldest existing system of glassworking and is responsible for most of the finest artistic glass creations in the form of ves sels, as well as a considerable, though now decreasing, variety of utilitarian articles, such as tumblers. Some of the tools re quired are shown in figs. 3 and 4, comprising blowpipes, at the wider end of which the necessary quantity of glass is obtained by dipping into the pot ; a smooth iron plate called a "marver" (or, as an alternative or an adjunct a wooden shaping block), on which the gathered glass is rolled to produce regularity of shape, pincers and shaping tongs (figs. 5, 6, 7, 8), flattening boards (figs. 9 and io), calipers (fig. I I), compasses (fig. 12) and shears (figs. 13 and 14).

The glassmaker sits at a chair (fig. 15) having projecting arms shod with strips of iron across which he rolls the blowpipe back wards and forwards when engaged in shaping the body of any glass article of circular cross section. Figs. 16-20 illustrate the process of making a wine glass with a drawn-out stem and blown foot. The partly shaped and blown gathering (fig. 16) is further blown into the shape of the bowl and a knob, formed by pinching (fig. 17) is drawn out into a stem (fig. 18) to the end of which a small bulb, blown by an assistant, is stuck (fig. 19) and opened out and flattened (fig. 20). The blowpipe is then cracked away by a wet tool, the wine glass held by the foot in a holder (a "gadget") and after being reheated at the mouth of the furnace until soft, the excess glass is sheared away, and, if desired, the rim pressed back to form a flange (fig.

2I).

Casing, inlaid enamelling, threaded and millefiori work are all done at the furnace.

Iridescent surface effects are produced by treating the hot glass article by the vapours of salts (tin chloride, ferric chloride, etc.).

The handmaking of window glass, in which cylinders 5 ft. 6 in. to 6 ft. long and 12 in. diameter are blown, split and flattened out, is another example of freehand working. It is dying out except for stained glass and special types like those made by the ancient craftsmen.

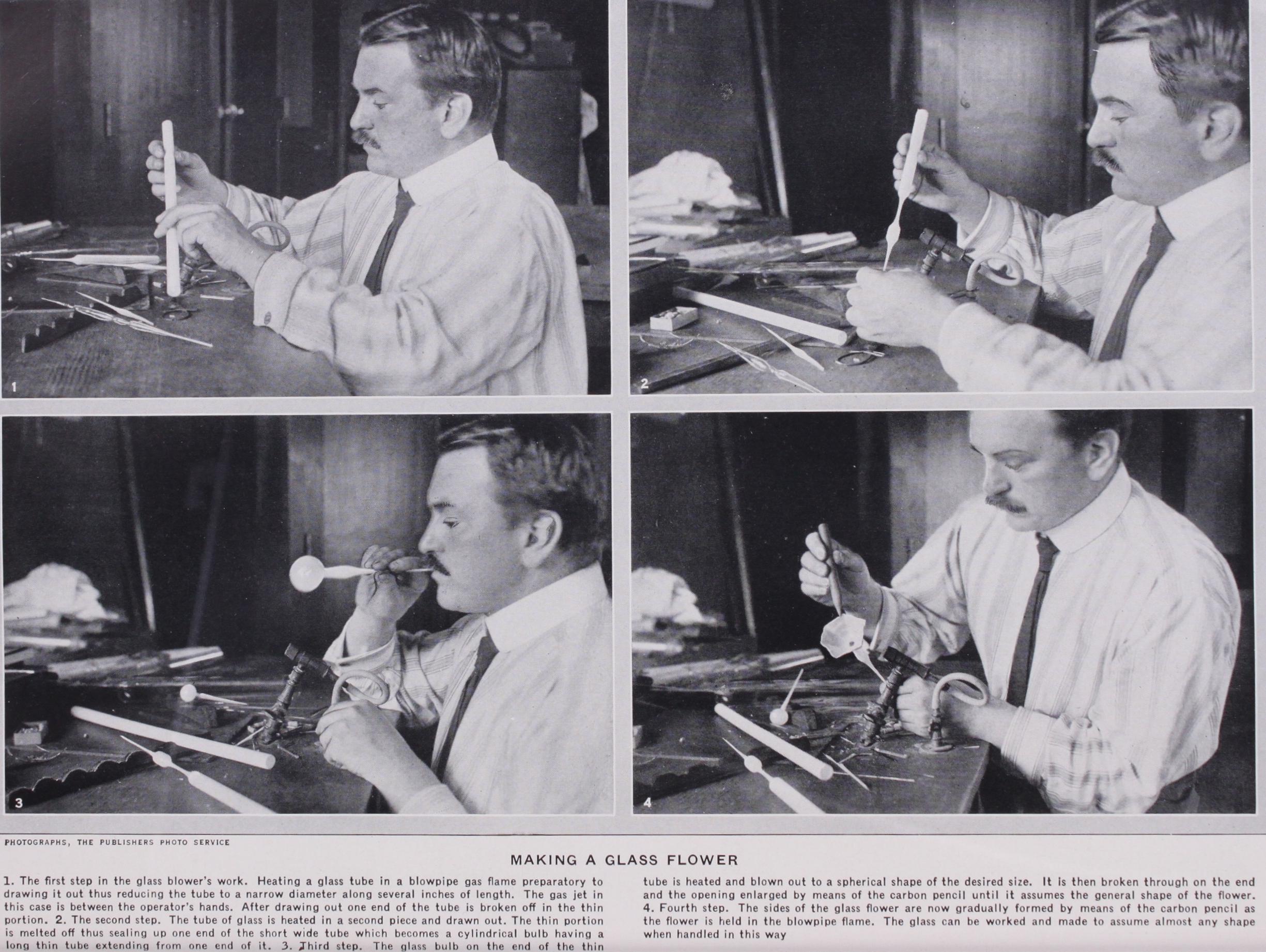

The lampworking industry converts glass tubing and glass rod into innumerable articles. A piece of glass tubing is rotated in the flame of a blowpipe (usually coal gas and compressed air, but for very hard glasses coal gas and oxygen or even hydrogen or acetylene and oxygen) and softened, after which the tube may be drawn out, the ends sealed, bulbs may be blown in various ways or joints made. The following are branches of the lamp working industry: (A) Electric filament lamp and radio-valve manufacture, although the sealing-in processes are now done al most entirely by automatic machines. (B) Light-blown scientific and surgical apparatus; test-tubes, ampoules, glass condensers, absorption bulbs, X-ray tubes, thermometers, etc. (C) Glass eyes. (D) Beads, artificial gems and fancy goods.

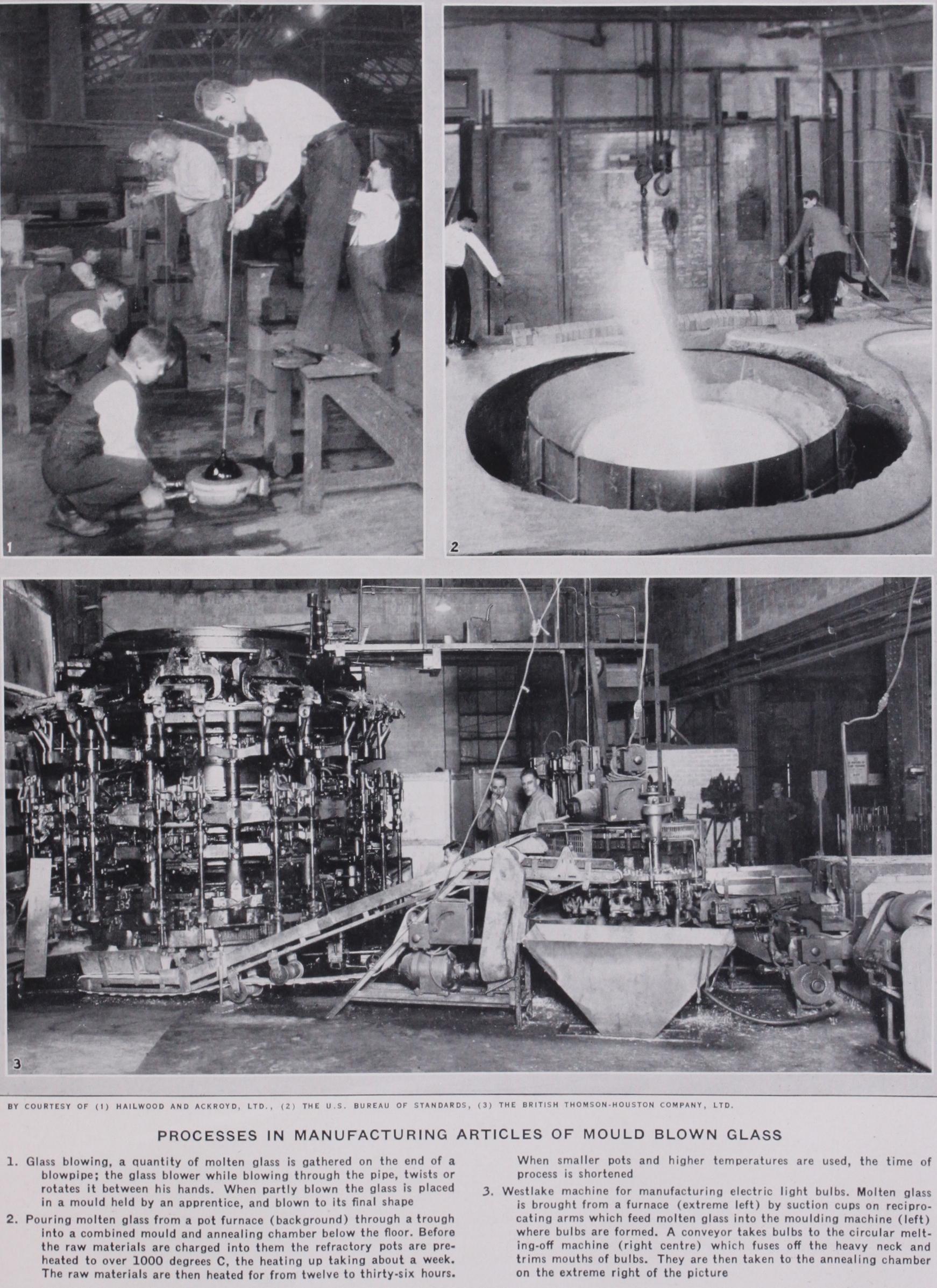

Mould Blown Glass.— Moulds are almost always of cast iron, although on the continent of Europe wooden moulds are frequently employed when only small quantities of an article are needed. The mould is hinged to open and shut, and angular shaped articles may require moulds with two or more hinges. The interior surface of a mould may be covered with a lubricat ing paste to prevent scratching of the glass and is known as a paste mould. If used dry, it is often described as a hot mould. The requisite amount of glass, if hand operation is in question, is gathered on a blow pipe, marv ered into shape, partially blown up and then lowered into the mould which is afterwards tightly closed and the final blowing given. When an article of circu lar cross section is to be made it is usually rotated as it is blown.

Blowing machines carry one or more moulds. (For glass bottle blowing see the article on BOTTLE MANUFACTURE.) The Westlake machine for making electric light bulbs carries 24 moulds and blowing heads. The glass is gathered by a ram which projects forward into a trough containing the molten glass, and obtains the charge which is conveyed to the mould. The operation of this particular machine has steadily been improved so that in the latest types as many as 120,000 bulbs per day have been made (1928).

Pressed Glass.

Pressing is used for a great variety of thick walled articles such as dishes of all kinds, thick-walled tumblers, jars, reflectors, pavement lights, pressed lenses, tiles and elec trical insulators. A charge of glass is poured into a mould and a plunger brought down into the mass, pressing it into all parts of the mould. A glass which is soft and not too quick in setting must be used for this process. The moulds may be blank or may bear a more or less intricate pattern. Pressed glass tumblers are now made in large quantities by pressing machines carrying eight or more moulds on a rotating table.

The Drawing of Glass.

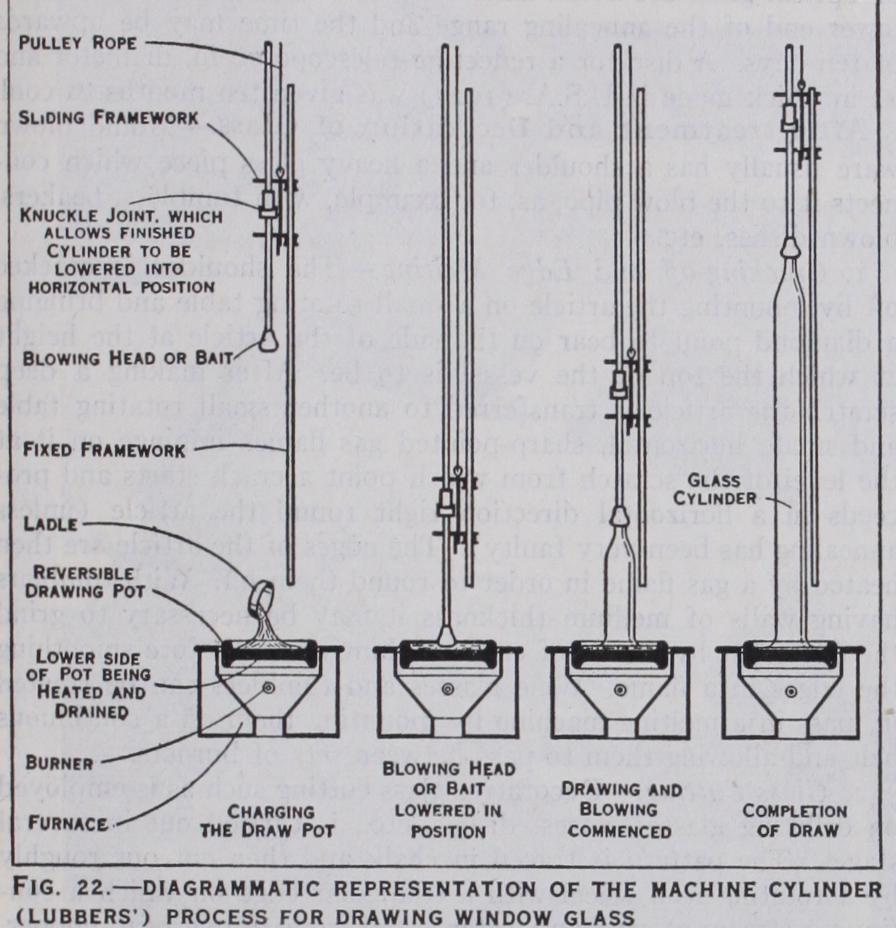

This process is exemplified by the manufacture of window glass and of glass tubing. The manufac ture of ordinary window glass by hand has disappeared from the U.S.A. and from Belgium, and is rapidly being displaced in other countries. The machine cylinder process, due to Lubbers, is still operated in America, England and France. The requisite quan tity of glass (about 55o lb.) is ladled from a tank furnace into a hot shallow fireclay pot and a blowing head let down into it, and after establishing contact, is drawn up steadily as may be seen in fig. 22. Cylinders up to 4o ft. long and 36 in. to 4o in. diameter are thus drawn. They are cut into sections, each is split, placed in a flattening furnace on smooth stone, and when suffi ciently hot and soft, smoothed out by a block of wood.

Processes for drawing the sheet direct are now in widespread use. The Libbey-Owens process draws the glass from a trough fed from the main tank furnace, the sheet passing over a roller (fig. 23) and being drawn horizontally through the annealing fur nace which is 200 f t. long. Two such machines can be operated by a single glass melting furnace. The rate of drawing is from about 26 in. to 72 in. per minute, and is continuous night and day. In the Fourcault process (Belgium) the sheet is drawn vertically upwards from drawing chambers fed from the melting tank. The line of the drawing chambers forms a T-piece with the line of flow of the glass from the melting tank (fig. 24). The glass oozes through a slit in a fireclay floater, is drawn upwards and immediately chilled by water coolers before it reaches the asbestos rollers which propel it up through the annealing cham ber which is only about 20 ft. long. By this process glass up to about 6 ft. wide may be drawn (usually 4 ft. to 5 ft. wide) and from four to ten machines may be fed from one melting furnace.

Glass tubing and glass rod may be obtained by drawing out the glass from a cylindrically shaped mass, hollow in the case of tub ing, solid in the case of rod. The process is now carried out mechanically and continuously by the Danner (American) tube drawing machine (known also as the Libbey-Owens tube-drawing machine) and by the Philips (Holland) machine. In the for mer fluid glass falls on and spreads over an inclined tapered fireclay mandrel through which air under slight pressure is blown if tubing is required, and the glass as it flows from the end is drawn away by a machine, the tubing in between the mandrel and the machine passing over pulleys (fig. 25). From zoo to 50o ft. per minute may be drawn.

Rolling of Glass.

This process is employed for the manu facture of plate glass, figured sheet glass and reinforced or wire glass. Glass is melted in open pots and when ready, the pot is transferred by a crane to a casting table of iron and distributed in front of a massive iron roller which traverses the table from end to end, rolling it out into a sheet, usually about - in. thick. The lower surface is roughened by the adherence of sand scat tered over the table to prevent sticking and the upper surface is marked either by groovings or other markings in the roller designed to prevent sticking of this implement. The large rolled sheet passes down an annealing furnace about 40o ft. long and after being discharged is cut into suitable pieces, set in plaster of Paris on circular grinding tables (up to 36 ft. diameter) and ground by iron-shod runners using a mixture of water and sand as abrasive. Af ter grinding both faces the glass is reset on similar tables and polished with similar runners, but shod with felt and using water and rouge instead of sand. In the Bicheroux process, the glass is cast between two rollers, enabling thin plate to be rolled and saving much of the time and cost of grinding.

For figured glass the rollers bear a pattern. (For wire glass see REINFORCED GLASS.) Optical Glass.—The term is usually regarded as applying to the highest qualities of glass used for telescopes, microscopes, camera lenses and scientific instruments of precision and not to spectacle lenses and pressed lenses for which inferior glass is used. Optical glass is always purchased on specification and must be supplied as having definite refractive index (that for the D-line, dispersion and dispersion constant (v). These are the prop erties on which the optician bases his calculations of achroma tizing two or more lenses, that is, of building up lens systems in instruments without colour fringes. The importance of high quality optical glass is out of all proportion to the quantity made and the manufacture is seldom a profit-making venture. Three firms in Great Britain, one in Germany and one in France make it; about nine optical glass companies in the U.S.A. make all that is produced in America. Messrs. Chance Bros. make some i 20 varieties and the following six from their list are selected to illus trate the range of optical properties: The "crowns" were originally confined to alkali-lime-silica, and the "flints" to alkali-lead oxide-silica glasses. Partial substitu tion of silica in the former by boric oxide gives boro-silicate crowns ; and by phosphoric oxide or fluorine, phosphate crowns and fluorcrowns, respectively. Substitution of lime by barium oxide or zinc oxide in crown glass gives barium crowns or zinc crowns; lead oxide by barium oxide in flints gives barium flints. "Light," "medium" and "dense" refer to density. Lead oxide tends to produce high refractive index ), high dispersion and low value of v. Barium oxide leads to moderately high and dispersion and still fairly high v. The effect of each 1% of the oxides soda, potash, lime, lead oxide, barium oxide has been systematically worked out, so that the approximate composition of a glass required to fulfil certain optical conditions can be cal culated (although this does not imply that it can successfully be melted).

The essentials of manufacture are (I) fireclay pots of low iron oxide content and as resistant as possible to corrosion by the glass, (2) sand and other raw materials as free as possible from iron oxide. Af ter being melted the glass is stirred for some hours to obtain homogeneity and freedom from bubbles and then slowly cooled, still stirring until too stiff to continue. The pot of glass is cooled in several days to ordinary temperature and cracks irregularly into variously shaped and sized pieces which are carefully selected, softened sufficiently to be moulded into slabs, the ends of which are polished to examine the glass for striae and bubbles, and sold in block form. Large discs for telescope refractors or reflectors are cast into a mould.

Annealing Glassware.

Glass is a poor conductor of heat. Hence, when cooling down and setting, the outer layers set hard prior to the inner, the contraction of which is retarded by the rigid outer layer. Stresses are thus set up in the glass. Thus, the outer layer may be in compression and the adjacent layer in tension. The working of glassware by tools or in metal moulds must naturally produce a rigid outer layer before the inner layers are set. A piece of hot glassware in which stresses are small or negligible can be prevented from developing stresses by retarding its rate of cooling appropriately, especially over what is known as the annealing range; whilst glassware which is stressed can be rendered relatively free from stress by maintenance for a suitable time at a temperature within the annealing range. Once the temperature falls outside this range the cooling can be rapid without modifying the distribution of stresses or setting up per manent stresses if they have previously been removed.Arrangements for annealing, therefore, consist essentially of some hot chamber maintained at a temperature within the an nealing range for a specified time and some means for cooling the glass at a controllable rate. This may be done in kilns or in lehrs. The latter consists of a hot chamber followed by a long tunnel in which cooling off occurs, a conveyor belt carrying the glassware traversing the hot chamber and the tunnel. For com mercial articles the temperature maintained in the hot chamber, either by gas or oil burners or other firing, or, again, in the latest methods, by the heat of the newly formed article, is the upper limit of the annealing range because the time required for anneal ing is greatly reduced thereby. For lead oxide glasses this upper temperature may range, according to composition, from 450° to ; bottle glass for window glass 55o° to ; whilst for chemical glasses it often exceeds 600°. Thin-walled articles, such as electric light bulbs, may be rapidly annealed in a few minutes ; the thicker the article the longer the time. Slabs of optical glass are often annealed at a temperature towards the lower end of the annealing range and the time may be upwards of ten days. A disc for a reflecting telescope 7o in. diameter and 12 in. thick made in U.S.A. (192 7) was given ten months to cool.

After-treatment and Decoration of Glass.

Mould blown ware usually has a shoulder and a heavy glass piece which con nects it to the blow pipe, as, for example, with tumblers, beakers, blown dishes, etc.I. Cracking-off and Edge Melting.—The shoulder is cracked off by mounting the article on a small rotating table and bringing a diamond point to bear on the side of the article at the height at which the top of the vessel is to be. After making a deep scratch the article is transferred to another small rotating table and small, horizontal, sharp-pointed gas flames impinge on it at the level of the scratch from which point a crack starts and pro ceeds in a horizontal direction right round the article (unless annealing has been very faulty). The edges of the article are then heated by a gas flame in order to round them off. With tumblers having walls of medium thickness it may be necessary to grind the edges flat by means of carborundum wheels before smoothing the edges in a flame. Wine glasses and tumblers can be treated in mass in a melting machine by mounting them on a continuous belt and allowing them to pass between sets of burners.

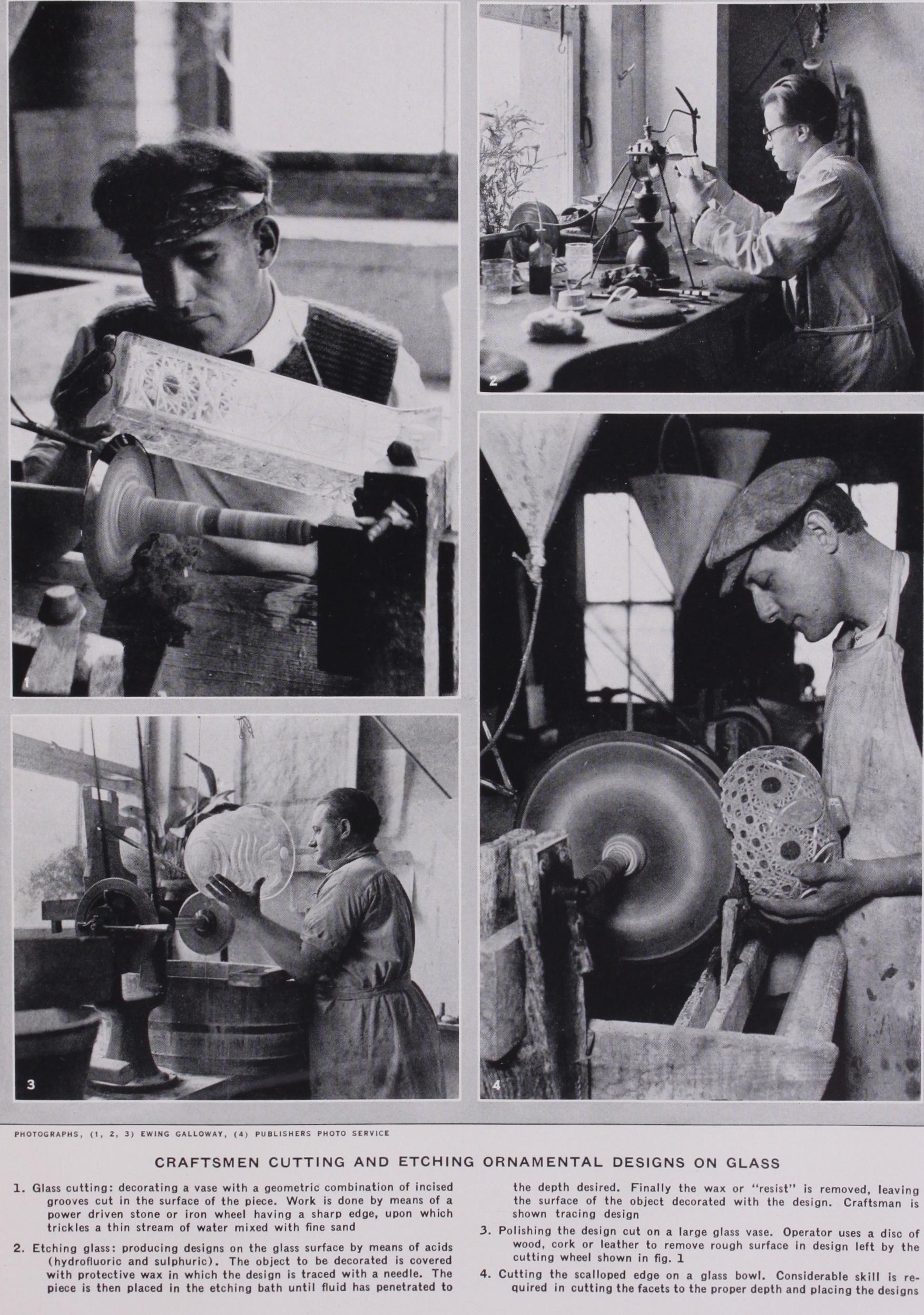

2. Glass Cutting.—Decorative glass cutting such as is employed on drinking glasses, vases, dishes, etc., is carried out in several stages. The pattern is traced in chalk and then cut out roughly by a rotating iron wheel with a triangular edge on which a con tinuous stream of sand and water is fed from an overhead hopper. The actual cutting is done by the sand under pressure from the iron wheel. The rough cutting is then smoothed by a stone wheel, Craigleith stone being much used in England, as well as artificial stone wheels. Polishing is now frequently done by dipping in a mixture of concentrated hydrofluoric and sulphuric acids. (Pl. II.) 3. Engraving.—Engraving is done by rotating copper wheels mounted in the chuck of a small lathe. The wheels, which vary in diameter from i - in. to 4 in., according to the size of the work to be done, are fed at their edges with oil containing fine emery powder.

4. Etching.—Electric lamp bulbs are now given an opal ap pearance by frosting them internally, the process depending on treatment with a solution of which the essential constituent is hy drofluoric acid. Glass decoration may also be carried out by a similar etching solution. For deep line etching a solution con taining one part of concentrated hydrofluoric acid to four or five of water is employed. When a matt or dulled surface is to be produced a mixture such as the following is employed: Ammo nium fluoride, 5; hydrofluoric acid, 2 ; water, 5. This mixture is best applied with a brush. Parts of the article which are not to be etched are protected by a resisting medium made up from a mixture of asphalt, resin, beeswax, Venetian turpentine and recti fied turpentine, one such mixture containing these materials in the respective proportions zoo, 300, 15o, zoo, 1,00o.

5. Sand Blasting.—A matt but rather rough surface is pro duced by the process of blowing a stream of sand at considerable velocity against the glass surface to be decorated or marked (such as in badging with a number or other device) the parts of the glass to be marked being exposed through a metal stencil plate. Historical.—Much of the earliest glass known has been found in Egypt and has suggested that country as having given birth to the art. Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie, however, regards objects earlier than about 1400 B.C. found in Egypt as of foreign im portation, the products of an earlier development in Syria. Glass has been found in the Euphrates region of date 2500 B.C. The earliest known factory was that discovered by Petrie at Tell el Amarna in Egypt of date 14o0 B.C. From this time onwards the art of glassmaking began to flourish in Egypt, the influence of foreign glass craftsmen being assigned by Petrie as the cause of the comparatively rapid development. Until shortly before the Christian era, the use of the blowpipe appears to have been un known, the glass being first worked into rods or threads, and these in turn being softened and worked round a core of sand and welded together into the shape of the vessel. The analysis (B. Neumann, 1926) of a sample of the colourless Tell el Amarna glass was silica 63.86, lime 7.86, magnesia 4.18, soda 22.66, potash o.80, alumina o.66, ferric oxide o.67%. The use of the oxides of copper, of iron and of manganese for colouring glass was known at this very early date. The manufacture of vases, coloured and decorated with Chevron patterns, and of beads, spread rap idly. About 1200 B.C. glass pressing in moulds was begun by the Egyptians.

Of early Assyrian glass-making we have no extensive knowl edge, but R. Campbell Thompson by his translations of inscrip tions on tablets of the reign of Ashurbanipal (668-626 B.c.) has provided us with much information about the materials used and methods of manufacture.

Egyptian glassmaking continued through the Greek and Roman occupations and received impetus from the existence of a big demand in the Roman market. Probably this demand led to the establishment of the art in Rome in the i st century B.C. Certain it is that under the Romans the art made such strides that from the point of view of form and of manipulative skill their highest attainments have scarcely been surpassed. The Portland vase, preserved in the Gold Room of the British Museum, is a mag nificent example of this skill. It was found in 155o in a tomb of the 3rd century A.D., but the vase itself is probably of the ist century A.D. It consists of a dark blue body surmounted by an opal outer layer which has been chiselled or cut to form groups of figures in relief. Glass cutting and engraving, glass mosaics (the latter already developed by the Egyptians) cameos, mille fiori and filigree work were all the product of the Roman art, whilst bottles and jars were extensively made. Glassmaking was carried on in many parts of the Roman empire, in Gaul, in Spain and on the Rhine.

On the break-up of the Roman empire the art was carried on most actively in the Eastern empire. The Greek workmen were largely preoccupied with the use of coloured glass as mosaics and their services for church decoration were in such request that they travelled far and wide plying their craft. In Syria glass making appears to have been widespread and in the early cen turies A.D., Jewish craftsmen were engaged in working imitation gems. Tyre, in the 12th century, contained many Jews engaged in glassmaking. The Mohammedans became interested in the art. We have definite records of the product of a factory at Sammara, in Mesopotamia, of the middle of the 9th century A.D., whilst in the i i th to the 14th centuries another peak of development was reached in the Arabian enamelled glass, applied to vases and gob lets and particularly to lamps for lighting mosques.

The next great epoch of glassmaking was the Venetian, extend ing from the beginning of the i 3th to the i8th century. It had its origin probably in the live contact of the Venetian trade with Syrian ports. Early in the 13th century there is evidence of a gild of glassmakers in Venice. Owing to the risk of fire within the city, the major operations of glassmaking were, towards the end of the 13th century, transferred to Murano and there greatly developed. During the 14th century, the craft was so important that separate gilds were formed and finally well established in the i 5th. Membership carried important privileges, but involved heavy responsibilities and various severe penalties were imposed by enactments between the 13th and i6th centuries on Venetian workmen who travelled abroad and divulged the art of glass making. Groups of them, however, and groups also from a rival establishment at L'Altare, travelled through western Europe, at tracted by considerable reward and gave fresh impetus to the art in the Low Countries, in England, France and Germany. The Venetian productions, especially of the i6th century, were grace ful in form and embodiments of the highest skill ever attained. The art of decoration attained a high standard and included lace pattern, filigree work, gilt and enamelled work and crackled glass. Copper aventurine glass was discovered in the 17th century. Window glass, ships lanterns and spectacle lenses were all made in the 13th and 14th centuries, whilst mirror making, particularly in the i6th and 17th centuries, became a lucrative trade.

Of the development of glassmaking in France, Germany and England subsequent to Roman and Greek influences our knowl edge is fragmentary only. A German worker, Theophilus, writing in the i 2th century regarded the art of making stained glass windows as essentially French and there are records of skilled glassmakers in Normandy for several centuries from the loth onwards, a band of whom at the end of the i i th century migrated to L'Altare on the Italian coast. Glassmakers from Lorraine, a district which produced much window glass in the i6th century, migrated to England during the i6th century and eventually es tablished themselves at Stourbridge and at Newcastle at the beginning of the i 7th century, opening up those important cen tres. The casting of plate glass was developed in 1691 by Louis Lucas de Nehou from an initial invention of Perrault in 1687. Very noteworthy, since the middle of the i 9th century, have been the artistic glass productions of Rousseau, Galle, Lalique Despres and Marinot.

Well-defined knowledge of German glass begins with the writ ings of Agricola at the middle of the i6th century, but the in dustry had been carried on for some centuries in the forests of Saxony and Bohemia. In the i6th century, Italian influence be gan greatly to stimulate the industry. Enamelling, gilding, paint ing and engraving were brought to a high level of attainment dur ing the two following centuries. In England much patient research has led to the discovery of a number of details about glassmaking operations in the early i8th century at Chiddingf old, in Surrey. There is little doubt that bands of roving glassmakers plied their craft for some centuries in the forests of Sussex and Surrey, and probably elsewhere prior to the big development, beginning about the middle of the i6th century, when in 1547 a band of Venetian workmen came to London to carry on their craft and to teach it. Various other bands followed and workmen from Lorraine, as already referred to, settled eventually in Stourbridge and in Newcastle. The efforts of Sir Robert Mansell, in particular, at the beginning of the 17th century helped to establish the industry. The English were the first to use coal for glass furnaces. They also introduced covered crucibles and about 167o began to em ploy a lead glass which soon became established as "English crys tal" glass, composed of potash, lead oxide and silica. Hitherto, in cluding all glasses from the early Egyptian to the Venetian, a soda-lime (including magnesia) -silica basis had been universal, except that in the forests of Bohemia and south Germany potash instead of soda provided an improved variant on the older glass. The new English glass could be made in thick articles suitable for cutting and engraving, and attained such popularity by the second half of the i8th century as to oust Venetian glass from favour.

The chief contribution of America to glassmaking has been the invention and application of wonderful automatic machinery be ginning with the Owens bottle machine (1899-1904) and fol lowed by other types for bottles and jars, electric bulbs, tubing and rod, window and plate glass. These inventions have placed America in the leading world position for quantity of glass pro duced and in recent years have made possible the manufacture of the articles named in countries such as South America, Japan, Australia and China, where skilled workers were unavailable.

Scientific Development.

The basis of existing technique for making optical glass was developed by P. L. Guinand, a Swiss, between 1774 and 18o5. The method was brought from France to England in 1848 by G. Bontemps. Faraday spent several years (1824-3o) in improving optical glass manufacture and Rev. V. Harcourt, working in the period 1834-65, in the latter years jointly with G. G. Stokes, was the pioneer in correlating the opti cal properties with the composition of glass. O. Schott and R. Abbe, in Germany, began their collaboration in 1879. The famous Jena works (188 2) sprang from their efforts and a mass of sci entific information about glass was published. The World War opened a new scientific era. The Department of Glass Technol ogy, University of Sheffield, was founded in 1915; the Society of Glass Technology in 1916. In America a Glass Division of the Ceramic Society was set up in 1918. The Deutsche Glastechnische Gesellschaft was founded in 1922 in Germany and several labora tories for research have subsequently been opened there. Japan has made a number of contributions to glass research.

Industrial.

Only in the United States, Canada and Great Britain are censuses taken of production. The unofficial statis tics are often uncertain and contradictory, and the data in the following tables must, therefore, be regarded as approximate for countries other than U.S.A., Great Britain and Canada: The number of employees is no longer a true measure of the glass producing power of a country. Commencing with the U.S.A. there has been in the last decade some diminution in the number of establishments and a check to increase of workpeople employed as the result of the invention of mechanical appliances. This process has spread to Great Britain and is now being felt on the continent of Europe.

In 1927, Germany was the biggest exporter of glass; but, rela tive to production, the two most important exporting countries are Czechoslovakia and Belgium. The former exported (1927) approximately 8o% of its glass production.

Window glass and plate glass constitute Belgium's chief glass exports. Of polished plate, Belgium was Europe's biggest pro ducer, with 37,66o thousand sq.ft. in 1926, less than one-third, however, of that of U.S.A. in the same year (128,857,875 sq.ft.).

(See also BOTTLE MANUFACTURE; GLASS [SAFETY] ; GLASS: ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Manufacture and General Glass Technology: R. Bibliography.-Manufacture and General Glass Technology: R. Dralle, Die Glasfabrikation, which was edited by G. Keppeler, vol. i. (Munich, 1926) ; A. L. Duthie, Decorative Glass Processes 0908) ; R. Hohlbaum, Zeitmasse Herstellung: Bearbeitung and Verzierung des feinen Hohlglases (Vienna and Leipzig, 191o) ; H. P. Waran, Elements of Glass Blowing (1923) ; F. W. Hodkin and A. Cousen, A Textbook of Glass Technology (1925) ; C. J. Peddle, Defects in Glass (1927) ; C. Hebing, Praktische Anleitung zur Ausfiihrung der Glasdtzung in ihren Verschiedenen Arten (1928) . Physical Properties and Theory: H. Hovestadt, Jena Glass and its Scientific and Industrial Applications (edit. and trans. by J. D. and A. Everitt, 1902) ; H. Schulz, Das Glas (Munich, 1923) ; E. Zschimmer, Theorie der Glasschmelzkunst als physikalisch-chemische Technik (Jena and Berlin, 1923) ; The Consti tution of Glass: A series of papers reprinted from the Journal of the Society of Glass Technology, publ. by the Soc. of Glass Technology (edit. W. E. S. Turner, Sheffield, 1927). History and Art: G. E. Pazaurek, Moderne Glaser in J. L. Sponsel's Monographien des Kunst gewerbes, No. 2 (19o9), and Kunstgldser der Gegenwart (Leipzig, 1925) ; E. Dillon, Glass (1907) ; W. M. Flinders Petrie, The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt (1909) ; H. Arnold and L. B. Saint, Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France (1913, 2nd ed. 1925) ; J. L. Fischer, Handbuch der Glasmalerei in K. W. Hiersemann's Hand bucker (1914) ; M. S. D. Westropp, Irish Glass: An Account of glass making in Ireland from the XVIth century (192o) ; H. J. Powell, Glass-Making in England (1923) ; F. Buckley, A History of Old Eng lish Glass (1925) ; R. C. Campbell, On the Chemistry of the Ancient Assyrians (1925) ; W. Buckley, European Glass (1926) ; J. D. Le Con teur, English Mediaeval Painted Glass, publ. by the S.P.S.K. (1926) ; W. A. Thorpe, English and Irish Glass, publ. by the Medici Soc. (192 7) ; L. Rosenthal, La Verrerie Francaise depuis Cinquante Ans (1927) . Scientific Periodicals: Optical Society, Transactions (5 num bers per annum, 1899, etc.) ; Society of Glass Technology, Journal (Quarterly, Sheffield, 1917, etc.) ; American Ceramic Society, Journal (Columbus, U.S.A. 1918, etc.) ; Glastechnische Berichte (Frankfurt, 1923, etc.) . Commercial and Technical Periodicals: Ceramique et Verrerie (monthly, Paris, 188o, etc.) ; Spechsaal (Coburg, 1915, etc.) ; The Glass Industry, publ. by the Glass Industry Publishing Company (a monthly, New York, 192o, etc.) ; Le Verre (monthly, Charleroi, 1921, etc.) ; Glass, publ. by Glass Publications, Ltd. (monthly, London, 1924, etc.) . Directories: Office of the National Glass Budget, U.SA., Glass Factory Directory (Pittsburgh, annual) ; Society of Glass Tech nology, Directory for the British Glass Industry (Sheffield, 1928) ; Adressbuch der Glasindustrie (Coburg, 1928). (W. E. S. T.)