Glass

GLASS, a hard substance, usually transparent or translucent, which from a fluid condition at a high temperature has passed to a solid condition with sufficient rapidity to prevent the formation of visible crystals. Glass consists primarily of a combination of silicic acid with an alkali (potassium or sodium). The combina tion of the raw materials was from the earliest times subject to considerable variations. As a general rule the silicic acid was pre pared from sand, as pure as possible and free from iron ; this sand was calcined and sprinkled with water until it became friable, and was then pulverized ; in some places flint, in others quartz, was also used. The potassium is in the form of potash, i.e., charcoal washed in lye; beech charcoal was always preferred. The sodium is obtained, under the name of soda ash, from seaweed ash. Glass may be divided into two main classes according to which of these alkaline ingredients is used. In well-wooded countries, particularly Germany, potassium glass has been made almost exclusively, while in coast-lands (Egypt, Syria, Spain, Venice) sodium glass was naturally preferred. As early as the middle ages, soda ash (rocchetta, salicor), as a costly product obtained by a secret pro cess, was an export in great demand, particularly from Egypt and Spain (Alicante). Apart from certain admixtures—some times accidental, sometimes intentional—such as tartaric acid, saltpetre, etc., silicic acid and one of these two alkalis formed the chief ingredients of all the glass made up to the 17th century. Not till then was calcium, particularly in the form of chalk, used to any great extent ; it produced greater clarity and purity in the metal, the best examples being found in the Bohemian "crystal glass," which, owing to these properties, very quickly conquered the world market. The addition of lead, an English discovery of the 17th century, further largely accentuates these superior qual ities in the metal, and adds high refractive power, great lustre and a full ringing tone, but the weight is increased and the toughness diminished.

Great importance has always attached to decolorizing agents, known as glass-maker's soaps. The necessary ingredients of glass are seldom found in a pure state; the iron particles commonly found in sand are particularly active in preventing complete absence of colour in the metal being obtained. For decolorizing, i.e., for neutralizing such impurities, manganese and arsenic have proved the most satisfactory agents.

For producing coloured glass, metallic oxides are chiefly used. Cobaltic oxide produces blue glass, cupric oxide green and red, chromic oxide yellow-green ; stannic oxide makes opaque white glass; red ruby-glass is obtained by the addition of gold; and so on. The colouring varies with the quantities of the oxides used, the method of admixture, the temperature, and the time during which they are heated, so that several tints can be produced with the same metal. All the treatises on glass-making written up to the 18th century consist mainly of recipes of this kind for colouring glass; great importance was attached to this process, because endeavours were constantly directed towards the production of first-rate imitation gems.

In addition to these raw materials, to produce a good, easily fusible metal a large percentage of old broken glass (cullet) is required. Even in the middle ages, fragments of antique glass were much,in demand among glass-workers; as early as the 13th century there was a treaty between Venice and Antioch dealing with the importation of cullet, and its acquisition has played an important part in the history of many glass-works.

Glass-blowing.

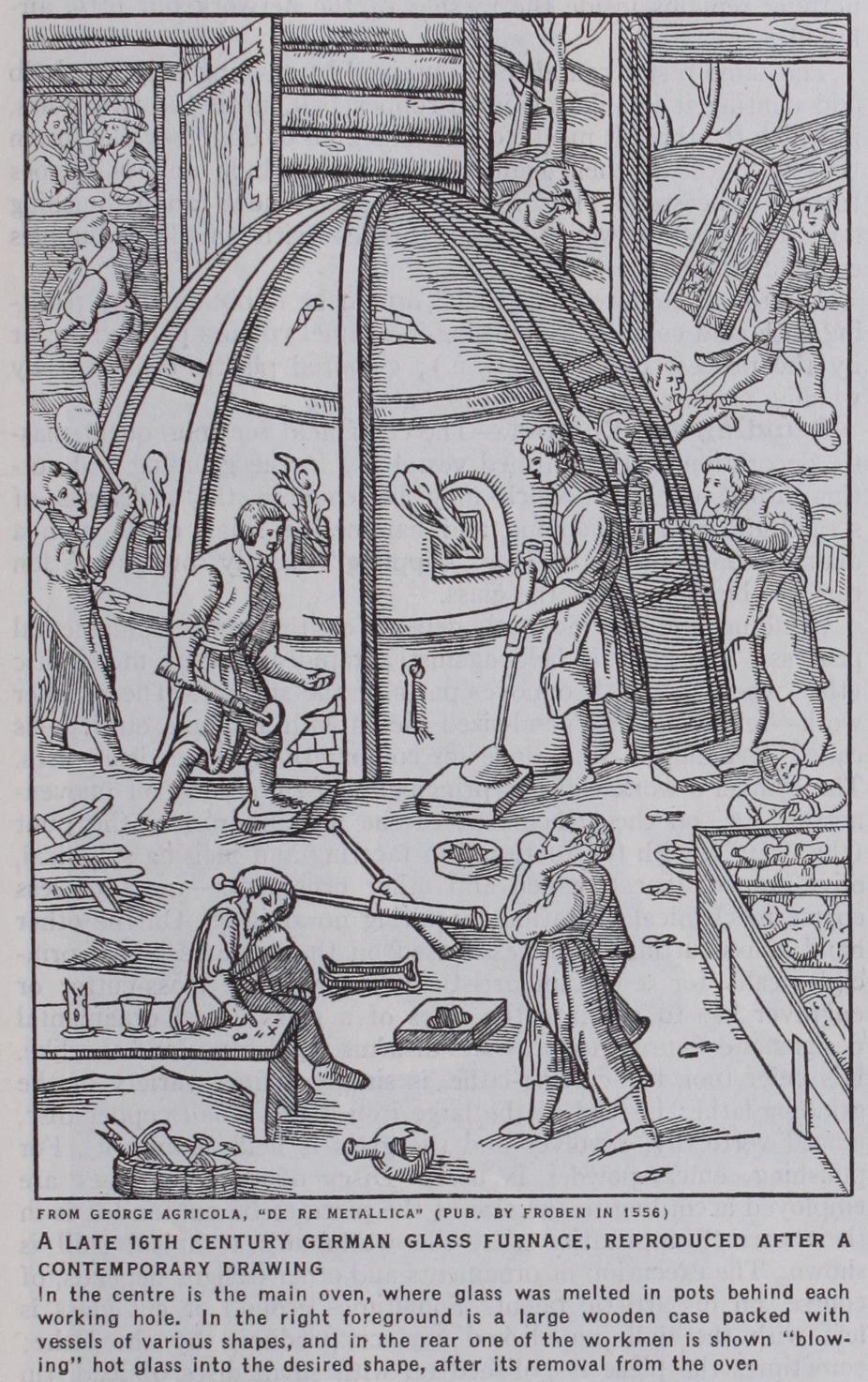

In the manufacture of hollow-glass the most important process is blowing. For this an iron tube about 5 ft. long, called the blowing-iron or pipe, is used. One end, which is knob-shaped, is dipped into the viscous mass of glass, a portion of which remains hanging from it. If the blower now blows through the tube from the other end into the pendent mass, a hollow bulb forms in it, and expands as more air is blown in. During this process, of course, the wall of the bulb becomes continually thinner. By swinging, by putting on the "marver" (a flat marble slab) or on the arms of an armchair in which the blower sits and then by rolling and by manipulation with simple tools, the bulb can now be given any shape desired. If a bottle is to be made, the bulb is drawn out lengthwise, and its lower end, which is to form the bottom, is "pricked," i.e., the bottom is pushed in with a blunt iron. In the cavity thus formed the "punt" is fastened with a drop of molten glass. When the bottle is thus resting on the punt, a drop of water is applied, and with a slight tap it is de tached from the blowing-iron ; the neck is then shaped as desired by welding a thread of glass round it, or in some other way. An other slight tap suffices to detach the finished bottle from the punt. To make a wine-glass, a quantity of glass is welded on to the lower end of a bulb, and by continued rotation of the blowing iron the stem is wrought out of this mass with a pair of tongs. Meanwhile another man has made a small bulb, which is now welded on to the lower end of the stem and knocked off from its own blowing-iron. By the action of centrifugal force aided by the "pressing-iron" ("Auftreibeisen"), this small bulb, under con tinued rotation, spreads and straightens out into a more or less flat disc, the edge of which is smoothed off with scissors. The punt is now again made fast to the underside of this foot, and the large bulb which forms the cup of the glass is knocked off from the blowing-iron. After this the bulb is broadened out with the pressing-iron, and the cup of the glass is shaped as desired with the "smoothing-iron." Finally the lip of the glass is cut with the scissors and fused all round. The glass is then knocked off the punt. During all these processes the material has to be frequently reheated.The glass can be moulded into any shape if the bulbs are blown into hollow moulds of stone, wood or metal, or, in the case of thick bowls, for example, if the glass-metal is pressed from within against the walls of such moulds.

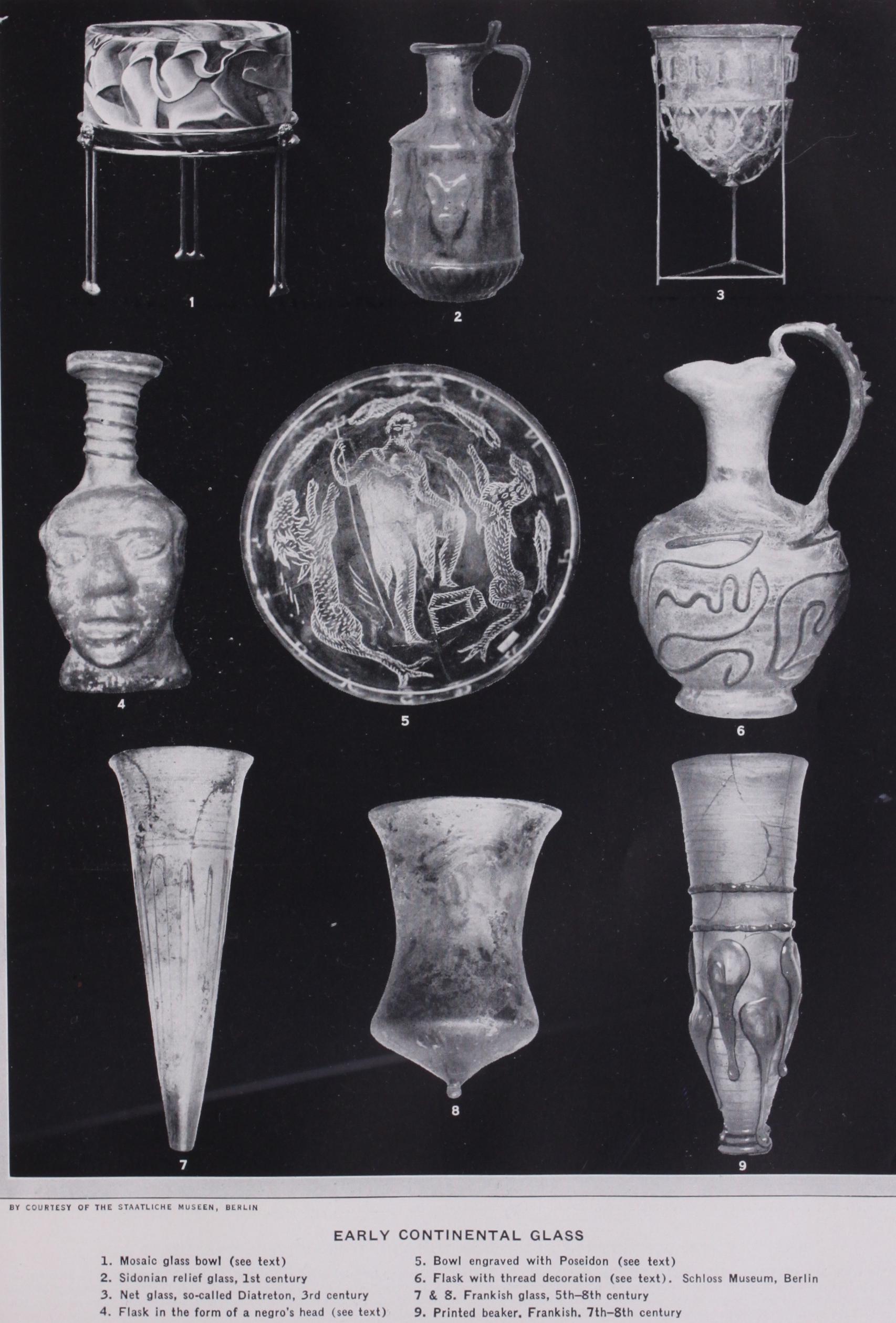

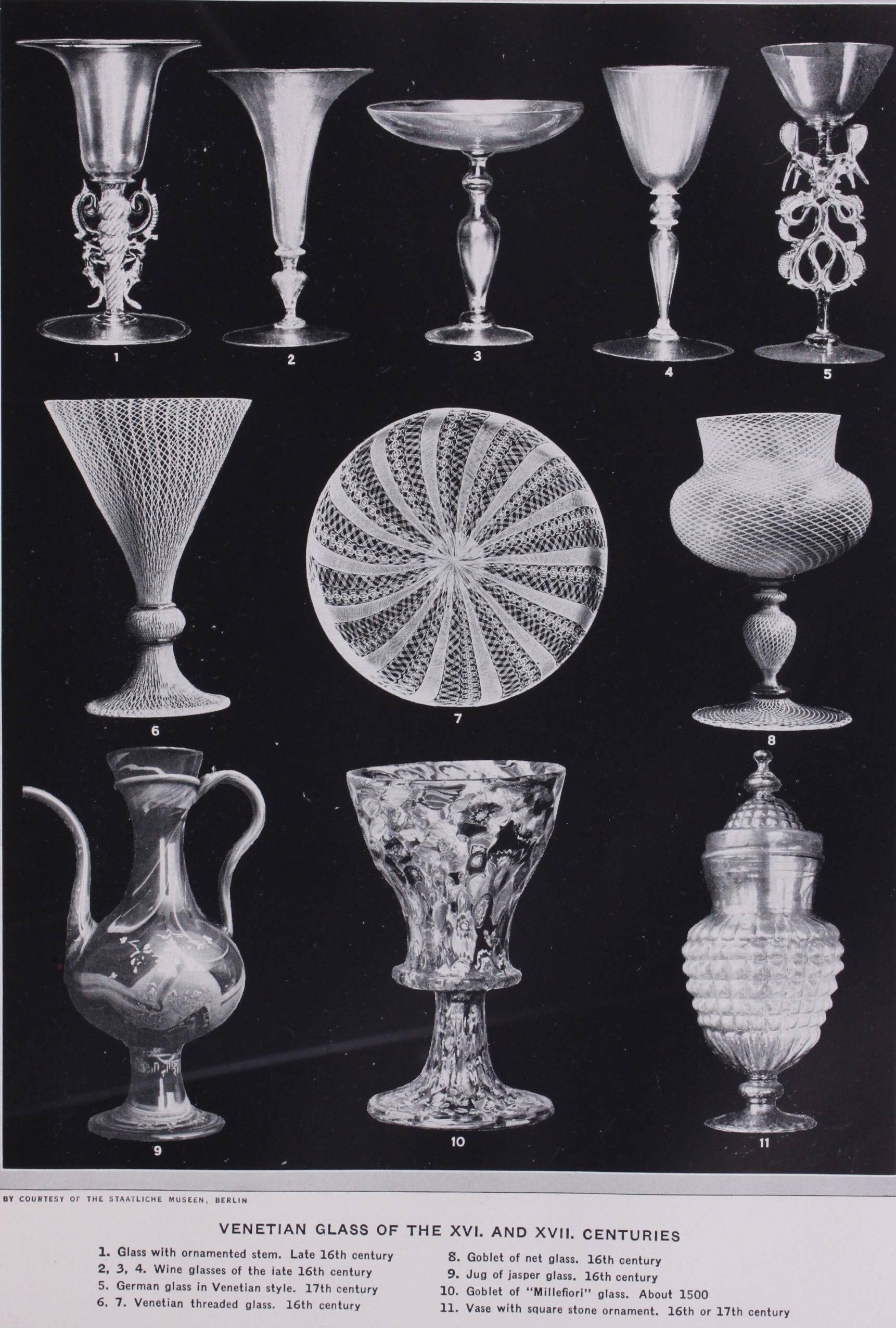

Coloured ornament in the metal is produced by pressing col oured glass threads into the still ductile surface of the vessel (e.g., Egyptian unguent jars), or by mixing glass of different colours on a definite plan or at random. In many ancient mosaic glasses, for instance, and in the Venetian jasper-glass, there is no plan; a colour-sequence, of ten very strictly followed, is to be seen principally in spun glass and "millefiori" glass. The method of making "millefiori" glass is this : glass threads of various col ours are fused together into a bundle in such a manner that the cross-section shows a certain pattern—say a rosette, a geometrical ornament or a figure. This bundle is heated and drawn out longer, so that, while its diameter is reduced, the pattern in the cross section remains unchanged, though diminished in size. The bundle of threads is then cut up into small discs (cf. Plate V., No. 1). They are worked into vessels by being placed side by side on an iron slab and having a bulb of colourless transparent glass rolled over them; they become embedded in this, and it then undergoes other processes like any ordinary glass bulb. Any irregularities that may be left on the outer side are removed by gentle heating or by grinding.

Spun

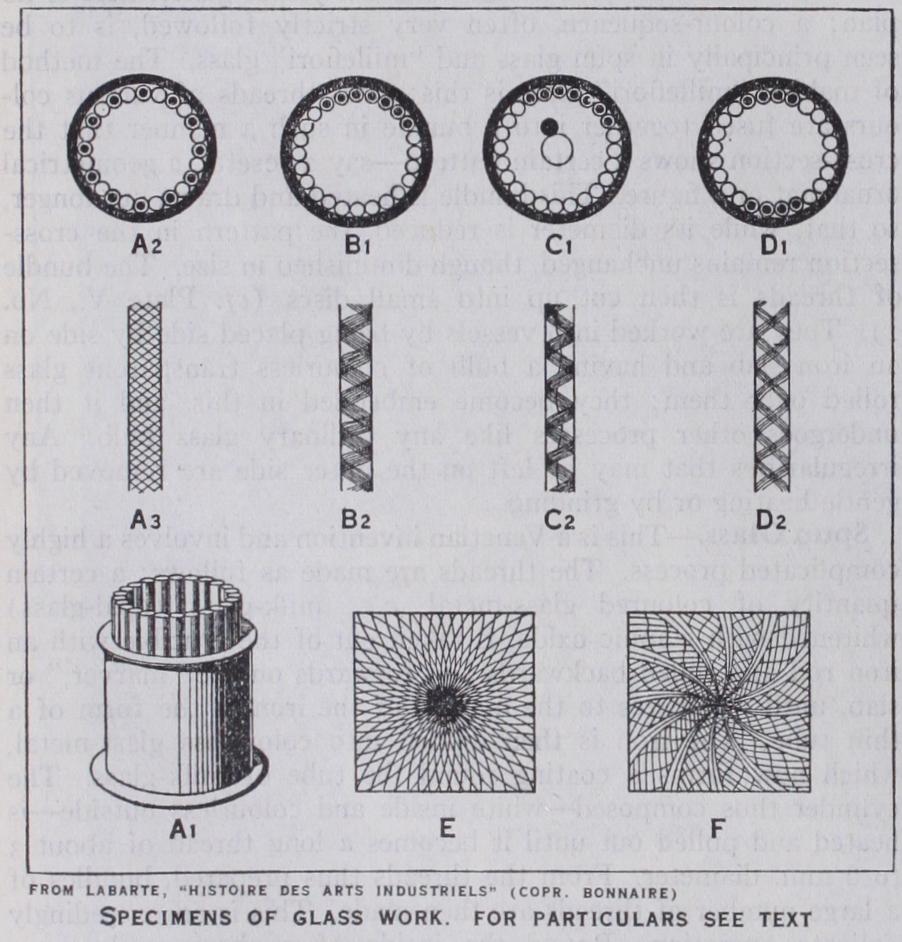

Glass.—This is a Venetian invention and involves a highly complicated process. The threads are made as follows : a certain quantity of coloured glass-metal, e.g., milk-glass (opal-glass) whitened with stannic oxide, is taken out of the crucible with an iron rod and rolled backwards and forwards on the "marver," or slab, until it adheres to the outside of the iron in the form of a thin tube. The iron is then dipped into colourless glass-metal, which now forms a coating round the tube of milk-glass. The cylinder thus composed—white inside and colourless outside—is heated and pulled out until it becomes a long thread of about 3 to 6 mm. diameter. From the threads thus prepared, bundles of a large number of threads are then made. This is an exceedingly delicate operation. Round the inside of a short earthenware cylinder, threads of milk-glass of the kind above described are arranged alternately with small rods of colourless glass in a definite symmetrical order (fig. A, i and 2). The hollow left in the centre is filled up with colourless glass-metal, so that the whole fuses together into a single compact rod of glass. This rod, on the circumference of which there are of course parallel white threads at equal intervals, is pulled out until its diameter has shrunk to almost nothing; and simultaneously the rod is twisted in both directions, with the result that the threads of white glass, which had previously been parallel, are now twisted round one another like the strands of a rope (fig. A3).Innumerable variations can be obtained by altering the ar rangement of the white threads. If, for example, we put seven of them all together on the side of the earthenware cylinder (fig. Bi) and fill up all the remaining space with uncoloured glass, by pulling out and twisting we get a wide spiral consisting of seven parallel strands (fig. B2) ; if we put four white threads on each of two opposite parts of the cylinder, in the finished rod we shall find two four-stranded spirals crossing (fig. CI and 2). If we carry one thread into the middle of the cylinder, it will form a white central column with spirals twining round it ; and if we shift it slightly out of the centre, the central thread itself will produce a corkscrew effect inside the spirals (fig. Di and 2) .

By other complicated arrangements of the white threads a great number of most attractive intricate patterns can be obtained. Vessels made in this way are called vasi a ritori.

In making a vaso a ritorti a cylindrical mould is again employed. The rods are again arranged in any desired order, with or without uncoloured rods between them, on the inside of the cylinder. They are then gently heated, and into the hollow cylinder which they form a bulb of colourless glass is blown from above ; they adhere to this bulb, and on further heating and expansion they fuse completely with its surface. They are then pinched together just above the end of the bulb, so that they all meet at one point, while the intervals between them on the surface of the spherical bulb increase as it expands. As the bulb is blown out still more, its walls become thinner, and the rods are naturally pressed flat, so that the patterns inside them are squeezed out wide. The bulb is now subjected to the usual further processes. If it is not rotated, the rods run together like meridians on a globe ; but if it is rotated while the other processes are going on, they form rhythmical spirals which cover the entire vase with their sym metrical whirling curves (figs. E and F).

A simpler method of combining the rods with the bulb has obtained latterly at Murano. The rods are laid in the desired order on a metal plate and are then heated, whereupon the hot glass bulb is rolled over them and they adhere to it.

A type of spun glass that differs from the others is reticulated glass (vasi a reticelli). It is made as follows: a considerable number of rods containing only one strand of milk-glass are welded on to the glass bulb at equal intervals, in such a way that the rods are not completely fused with the bulb, but take the form of ribs standing slightly out. The bulb is elongated and rotated at the same time, so that the threads now run spirally round it. A second bulb is produced in the same manner, but is rotated in the opposite sense during the process of elongation, so that the spiral twists run in the opposite direction to those on the first bulb. Both bulbs are then cut open, fitted one inside the other in the form of open cylinders, and fused by heating. The spiral threads now cross one another in a network, and as the separate raised rods leave small hollowed-out trough-shaped grooves between them, nothing remains inside the meshes of the network but little air bubbles.

The same result can also be obtained by making only one bulb and denting it in, like an india-rubber ball, until the two poles, in which the threads meet, touch. The kind of double-walled basin thus produced is then again shaped into a bulb and undergoes further processes. Thus reticulated glass shows an astonishing structure of interwoven spiral threads with small air-bubbles embedded between them.

Additional coloured superficial ornament is obtained by paint ing with cold colours, by burning-in enamel colours painted on, or by the process of gilding (q.v.) ; coloured plastic ornament by welding on threads, knobs, beads, etc.

Grinding and Cutting.

The chief field for subsequent plas tic decoration of the finished vessel lies in the grinding and cut ting processes, with which may be counted the processes of scratching with a diamond and hammering small dents with a diamond-point—"dotting" or "stippling." Lastly, ornamentation can also be etched into the glass.Grinding and cutting both depend on the same fundamental process. The glass is held against a rapidly-rotating metal disc (the "wheel"), which removes parts of the surface. The rougher work—removing only good-sized pieces with a simple outline—is called "grinding." It is done on comparatively large iron discs. The grinder's work consists principally in smoothing off uneven nesses, e.g., on the attachment to the blowing-iron or the punt (the "cap"), with the foot, and in faceting and incising spherical, olive-shaped, lancet-shaped and other ornaments—more or less coarse mechanical operations requiring no artistry. On the other hand, glass-cutting, a process based on the same technical prin ciple, calls for a certain artistic capacity. The glass-cutter or engraver has to cut into the sides of a glass vessel ornamental designs and figures, script, coats-of-arms, landscapes and the like. His chief tool, the cutting-lathe, is simply a finer variety of the grinding-lathe ; instead of the large iron disc a small copper disc, placed vertically, revolves and the glass is held against it. For polishing, emery-powder is used. Discs of different sizes are employed according to the size of the piece to be cut, and it is in their correct application that the workman's technical skill is shown. The execution of ornaments and other designs depends, of course, on his artistic talent. Sometimes ground or cut glass is left with the dull, unpolished surface produced by the lathe; sometimes the piece is polished up with small discs of lead, tin or wood ("burnishing"). The commoner and simpler method of glass-cutting is "intaglio cutting," the ornament being cut into the surface; in "relief cutting," which is more difficult, the orna ment is left standing out and the surface of the glass is cut away round it (e.g., the Portland vase [Pl. V., No. 51, the Hedwig glasses [Pl. III., No. 3], and Gundelach's work [Pl. VI., No. 6]).

Antiquity and the Early Mediaeval Period.

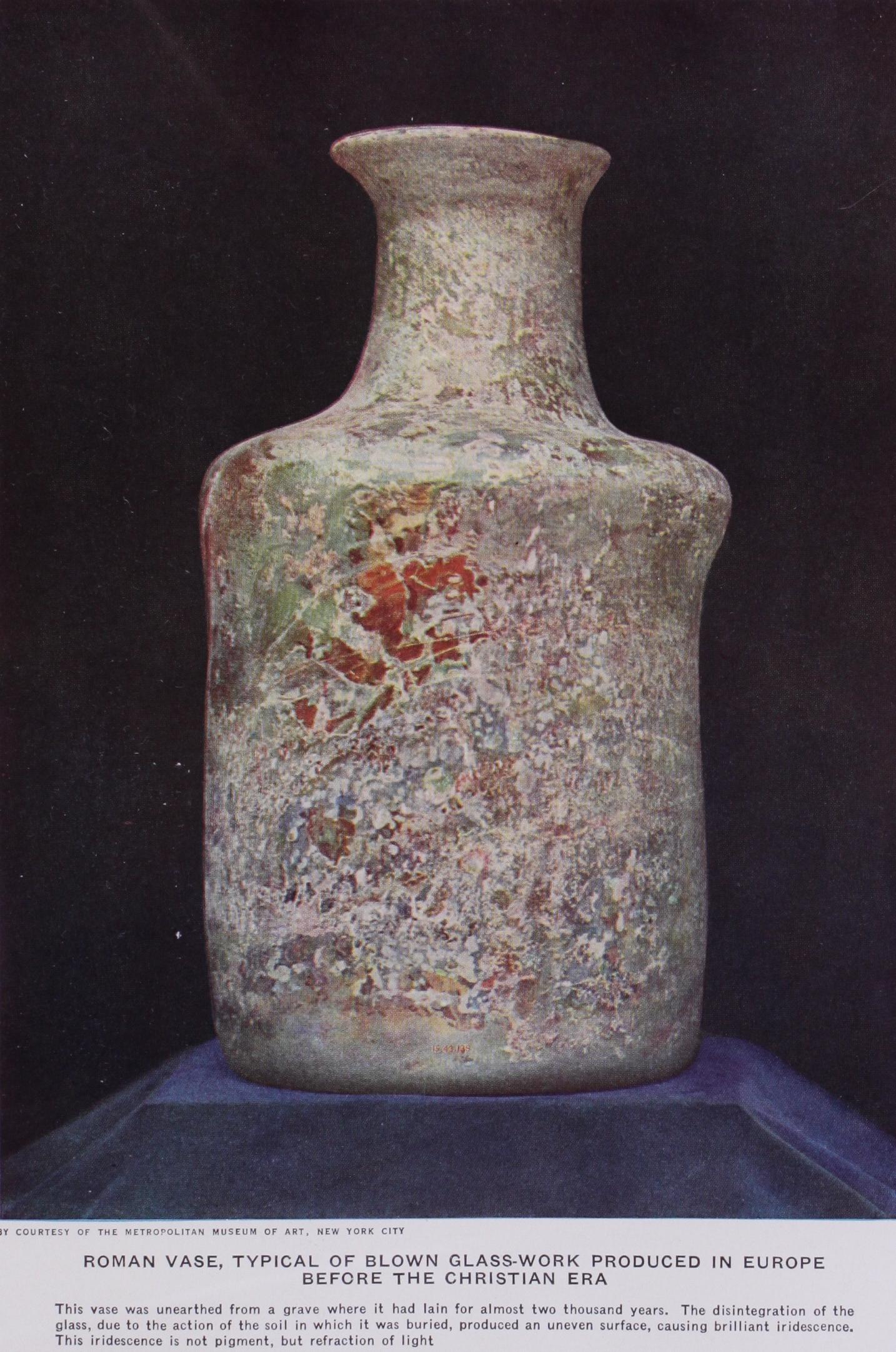

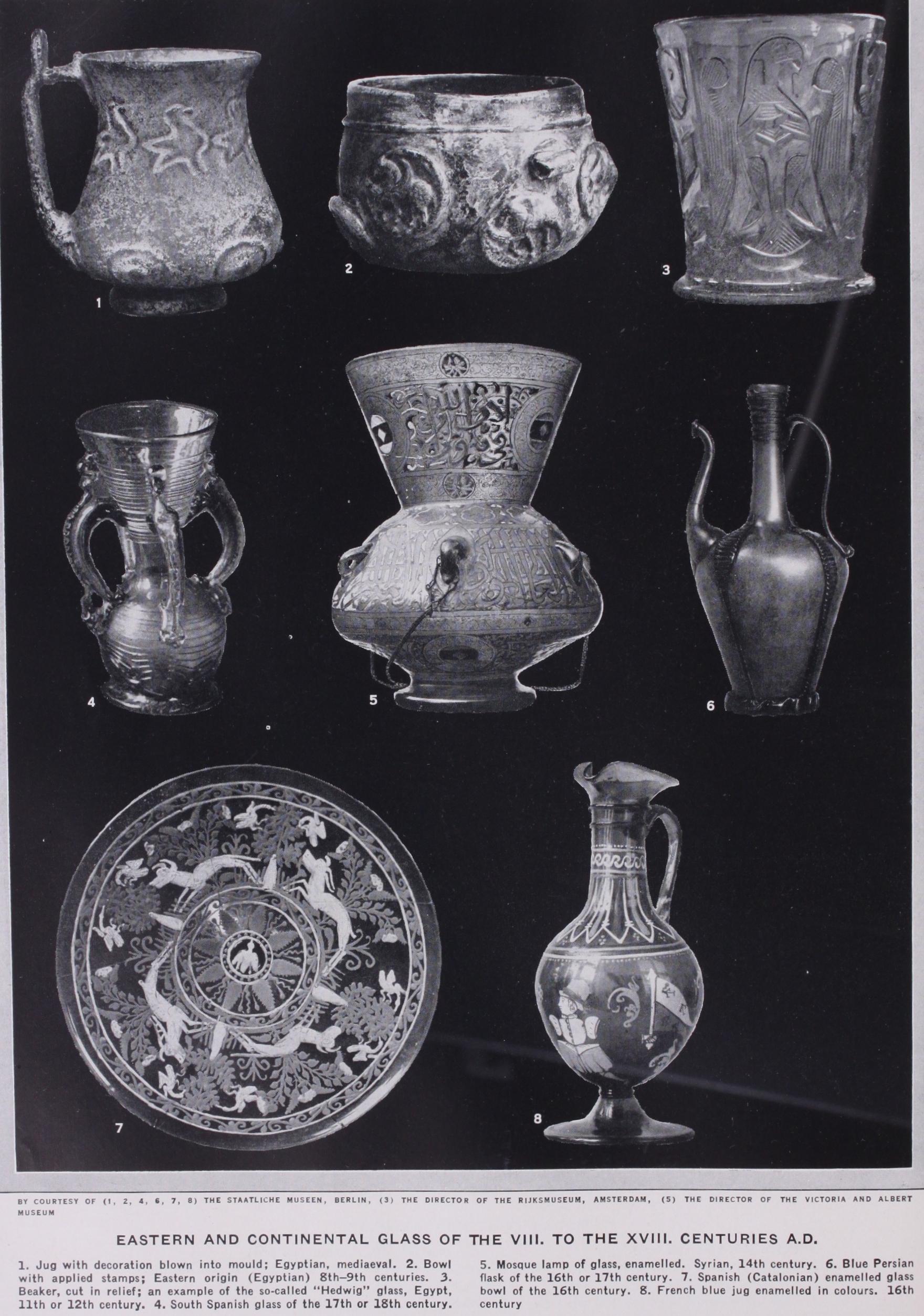

We cannot state with any certainty when and where glass was invented. Probably, however, it originated in Egypt (see EGYPT: An ,evt Art and Archaeology) for the oldest examples of glass-work known to us come from Egyptian tombs of the 4th millennium B.C. They are, however, merely pastes, generally of opaque coloured glass, which were worked into beads, amulets, and the like ; and the first glass vessels to which any date can be ascribed belong to the i8th dynasty (c. 150o B.c.). Even these vessels, however, most of which are very small vases or ointment-jars such as the balsam-pots shown in plate V., fig. 2 with particoloured enclosed threads on an opaque coloured ground, are made entirely by hand out of a viscous glass-paste. The invention of glass-blowing, which marked a turning-point in the history of glass, did not take place till about the beginning of the Christian era, in the time of the Emperor Augustus; and the place was the Phoenician city of Sidon. The early Sidonian relief-glass (Plate II., No. 2) is still blown into the mould, and still made out of coloured metal; de colourizing was soon learnt, however, at all events in Alexandria, whose glassware dominated the world market till late in the Roman imperial age. While Greece produced no glass, we know of glass works in Italy (Puteoli, Rome), Spain and Portugal (e.g., Tar raco), France and Belgium (e.g., Boulogne, Amiens, Rheims, Namur), and the Rhineland, where from the 2nd to the 4th century there were glass-works of high artistic quality in various places such as Troves, Andernach, Xanten, Worms, and above all Cologne. In Britain also glass-works were introduced from Gaul. Nearly all the technical processes of any real importance in the manufacture and decoration of glass were already mastered in antiquity. Freehand blowing, blowing into the mould (relief glass) (Plate II., No. 4), the working of glass while still plastic with tongs and various other implements to pull out studs or to produce bosses, the production of imitation coloured stones, gems and cameos, and even the making of window-panes, were practised in the glass-works of ancient times. Mosaic-glass was treated in masterly fashion in the ancient workshops, particularly at Alexandria, both in the form of ornamental slabs (see Plate V., No. I), which display highly complicated patterns and even figures, and in the form of vessels, bowls and vases, mostly in the flower-like "millefiori'.' patterns (see Plate V., No. 4). (The name was not invented till later, in Venice.) The finest ancient mosaic bowls with "millefiori" but also with ribbon patterns are the so-called vasa murrina (Plate II. No. I), which must have been ground out of a solid block of glass. Painting (cold with mineral colours, and by the warm process with enamel colours) and gilding were already employed in ancient times for decorating the moulded glass after completion. Gilding (q.v.) took the form of spreading gold-leaf on the surface and protecting it, as a rule, with an outer film of colourless transparent glass. Ornaments, inscriptions and figures were etched out of the gold. To the best-known types belong the so-called fondi d'oro (Plate II., No. 7), which have been found chiefly in the catacombs at Rome and in Rhenish graves; they are bowls or beakers with gold etching under the flat bottom, often on a blue and green enamelled ground. In the early days of this technique (2nd and 3rd centuries A.D.) they mostly depict mythological scenes and figures, and sometimes circus-combats or domestic scenes; in the 3rd and 4th centuries biblical scenes with pious toasts pre dominate. The ancient artists in glass obtained their plastic decoration by applying threads (Plate II., No. 6), or by welding on coloured projections in a wide variety of shapes; grinding and cutting also were already practised with great success. Glass cutting developed from simple lines and figure-engravings (Plate II., No. 5) to masterpieces of complicated technique such as the reticulated glasses (diatreta), with their freely-pierced network united only by frail bridges with the body of the vessel. These probably originated in the Rhineland. Alexandria, however, was the home of what is artistically the most important ancient glass work—the onyx glass, in which all kinds of exquisite designs are cut out in high relief with the cutting-wheel from layers of glass of various colours. Gems cut out of semi-precious stones in several layers served as models. The most celebrated example of this sumptuous genre is the Portland vase in the British Museum. It was discovered at Rome at the end of the 16th century ; in 1786 it was purchased by the Duke of Portland for i,000 guineas; and in 1845, in the British Museum, it was smashed to fragments by a madman. The scene represented (probably from the Peleus and Thetis legend) is cut out of a layer of white opaque glass, and stands out from a deep blue ground (see Plate V., No. 5) .

In the 5th century a powerful movement of artistic and tech nical decay set in in the glass-works of Gaul, Germany and Britain, which had till then remained wholly under the influence of the Roman provincial civilization. The range of colours dwindled, the processes of decolourizing and refining the metal were forgotten, and the earlier immense wealth of forms was reduced to a few simple forms of beaker, with primitive orna mentation consisting of superimposed threads and prunts. The beakers are spherical; some have a narrow flat bottom, but most of them could only be set down bottom upwards, when com pletely drained (Plate II., Nos. 7-9). The technical masterpieces of this Merovingian period are the "nose-beakers" (Russelbecher) (Plate II., No. 8) . From the Carolingian age onward we lose all trace of the hollow-glass industry; it undoubtedly continued to exist, but not until the 15th century, at the close of the middle ages, does a new recognizable development begin. For the absence of artistic hollow-glassware we have to compensate ourselves with the marvellous ecclesiastical stained glass (q.v.) of the Roman esque and Gothic periods.