Glasswork in Europe

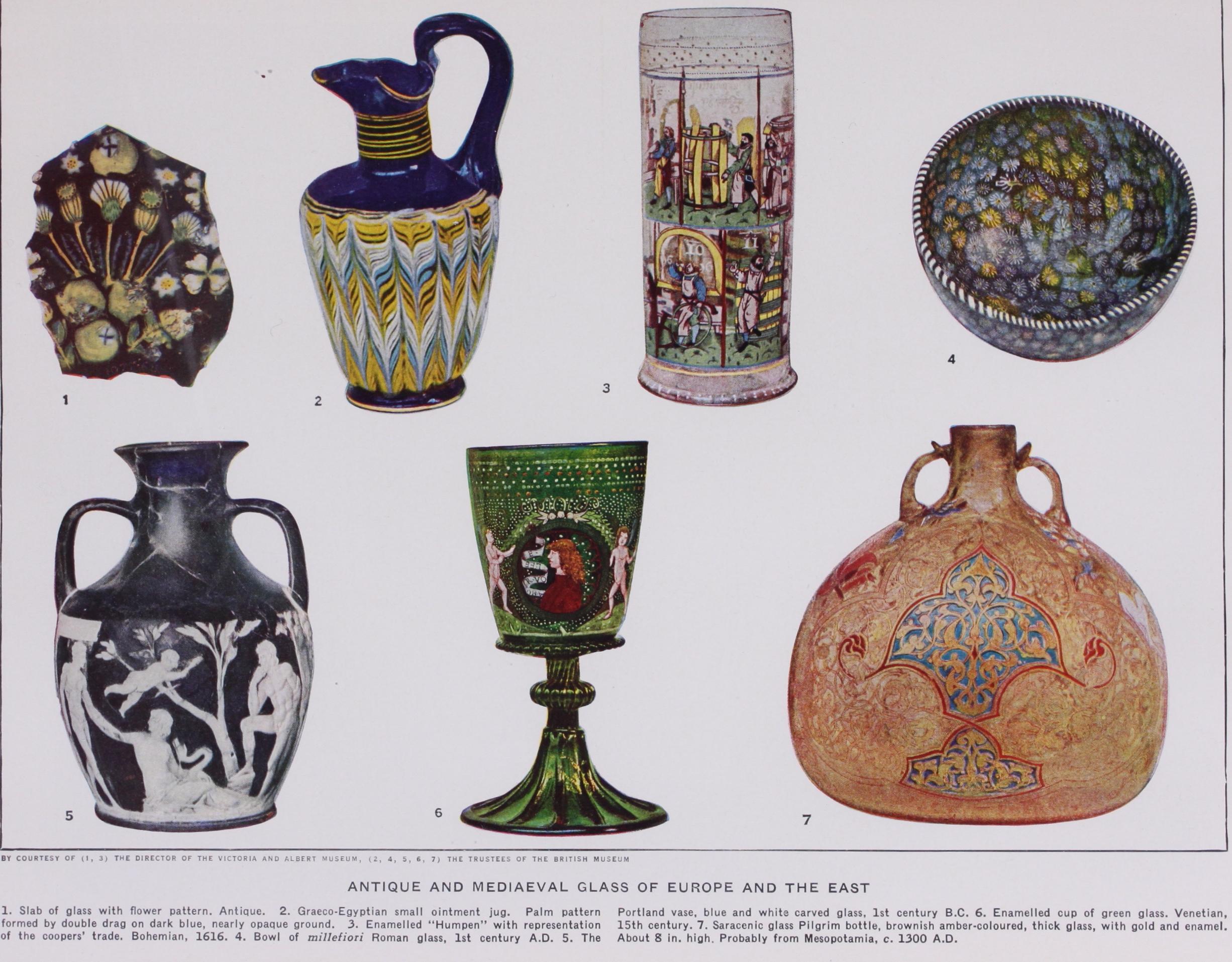

GLASSWORK IN EUROPE Venice.—Although our earliest knowledge of the Venetian glass industry dates from as far back as the nth century, no sign of artistic form is met with in Venetian glass until the beginning of the Renaissance—about the middle of the 15th century—and then there is not a trace of oriental influence. As early as 1291 the glass-ovens were removed en bloc to the neighbouring island of Murano, owing to the danger of fire; and draconian penalties were provided for glass-workers taking the secret of the process abroad. The i6th century was the great period of Venetian glass, which, in its technical and artistic perfection, had no equal in the whole world. Apart from the almost crystalline clarity of the glass, really artistic forms do not appear at Venice till the latter half of the 15th century, and then often in the form of late Gothic silver-work—in a strong, close superstructure on tively thick walls (see Plate V., No. 6). In the i6th century the Venetians found the proper expression for the sense of form that marked the Renaissance at its height, and also acquired the true style in glass-work, which arises solely out of the technique of glass-making. It was this period that gave birth to those spir ited, graceful, airy forms of vessel which are due purely to the glassblower's labour (Plate IV., Nos. 2-4). The contour of these glasses—bowl-shaped, calyx-shaped or bell-shaped--is of unprece dented elegance, and the baluster-stem, tapering down to a simple flat foot, varies widely in formation. The stem is often adorned with masks, lions' heads or pinched-out "wing" appendages (Plate IV., No. I). In the 17th century glass was not spared by the prevalent baroque spirit ; its forms become eccentric, compli cated, and too rich in ornament. In the 18th century the predom inance of Venetian glass was at last destroyed by the Bohemian and Silesian cut-glass. Besides the colourless soda-glass, Venice produced throughout her best period a wide range of coloured glassware. In the early days a great favourite was the marbled "agate" or "jasper" glass (Plate IV., No. 9). "Millefiori" glass (Plate IV., No. Io) was inspired by discovered antiquities, and the astonishing skill of the Muranesi is witnessed by the inven tion of spun-glass (Plate IV., Nos. 6 and 7) and its by-form, reticulated glass (Plate IV., No. 8), in the first half of the 16th century. To the same period belongs decoration in the forms of painting behind glass and diamond-engraving, while the won derfully artistic kind of Venetian glass which is ornamented with enamel-painting dates from the early period (c. 1460-1530). Gob lets, beakers, bowls, jugs, flasks (see DRINKING VESSELS) and other vessels were painted in multi-coloured enamel ; in the early period the body of the glass was almost always coloured (blue, green or violet) . Milk-glass was also often used for this purpose; but from 1490 onwards colourless transparent glass predominates. Triumphal processions and love-scenes, biblical and mythological scenes, half-length portraits (see Plate V., No. 6) and coats of-arms, and in the later period complicated grotesques, were fa vourite forms of decoration. In the 16th century many aristocratic German families had their coats-of-arms and portraits painted on glasses and goblets by Venetian enamellers.

"Venetian glass" became a generic name; but much so-called Venetian glass was made not at Venice, but in other Italian glass works (Treviso, Mantua, Padua, Ferrara, Ravenna, Bologna, Flor ence, etc.), to which the technique was generally brought by rene gade Venetians. The most serious competition however, that Ven ice had to meet came from Altare, near Genoa; the glass-makers there, who formed a close corporation, went abroad (to France, Flanders, etc.) year after year, but always returned to their homes and families. Glass-works on Venetian lines, a la f aeon de Venise, were founded all over Europe, mainly in the 16th and 17th centuries, by renegade Venetian glass-blowers and men from Altare. In 155o one was founded at Antwerp, in 1662 at Brussels, and others at Liege, Amsterdam , Haarlem, The Hague, Vienna (as early as 1428) ; Hall, in Tirol , where distinguished work, easily recognisable by its peculiar character istics, was produced; Nuremberg, Munich, Cassel, Cologne, Kiel, Dessau, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Lyons, Argentieres, Nantes, Nevers, Orleans, Paris ; and in London as early as the middle of the 16th century and also later. Many of the productions of these foreign daughter-establishments of Venice—only a few examples of which are shown here—cannot be distinguished, or only with difficulty, from the genuine Venetian ware ; at the same time, how ever, a number of these glass-works a la veneziana developed forms of their own, often of considerable artistic charm (Plate IV., No. 5).

Spain, France, the Netherlands.

In the middle ages the ancient Roman glass-works in Spain received the imprint of two different influences : in the south, the oriental influence, trans mitted through the Moorish domination; in the east (Catalonia) , the influence of Venice. The principal centre in the south was Almeria, famous for its artistic glassware as early as the 13th century. Here we find a mingling of indigenous and oriental motifs and ornament. Eccentric, fantastically-shaped vessels cov ered with handles, threads, rosettes, etc., are characteristic of southern Spanish glass (Plate III., No. 4). In and around Barce lona, on the other hand, we find, in addition to native forms (undoubtedly, however, originating in the East), a marked Ve netian influence. The shapes of the 16th-century enamelled glasses show a strong Venetian tendency, while their typical painting—generally pale green tendrils with multicoloured beasts and birds—point rather to the East; on the other hand, many forms revealing oriental influence (e.g., decanters with long spouts) bear the thread-ornament derived from Venice. Work a la f aeon de Venise was also done in various inland Spanish factories, as at Cadalso (Castille) and Toledo; at Villanueva de Alcorcon, and later at La Granja de San Ildefonso, there were glass-works from 1712 onwards—royal property from which produced ground and cut, gilt and painted articles, and also lustres and mirrors. They were influenced by French and German work. At the same time Spain and Portugal formed a considerable market for the Bohemian glass-works in the 18th century.In France the immigration of Italian glass-workers from Ven ice and Altare began as early as the 15th century; but there were also many native glass-works, especially in Normandy and Lor raine. Apart, however, from a small body of 16th-century enam elled glass, to which a French origin can be definitely assigned (Plate III., No. 8), and some graceful small glass figures from the Nevers works, France never produced glass of any artistic value. Greater attention was paid to glass for purely utilitarian purposes, such as window-panes, mirror-glass (see INTERIOR DECORATION), and other products of a more industrial kind. A manufacture des verres a la facon de Venise founded by Col bert in 1665 at Paris (Faubourg St. Antoine) grew later into the immense St. Gobain works. Whereas in the 18th century France was still wholly subordinate to other countries in the matter of fancy glassware, in the 19th century there was a strong upward movement, the result of which has been that France now leads in many branches of the fancy-glass industry.

In the Netherlands, where in the 16th and 17th centuries there were many glass-factories working both on Venetian lines and after German patterns, the new English lead-glass began to ex ercise a strong influence about the end of the 17th century. A large number of new works were established by Englishmen or operated with English hands, as at Haarlem, Middelburg, Ghent, and 's Hertogenbosch. In Holland glass-cutting was practised in the 18th century; the best master, Jacob Sang, lived at Amster dam. The pride of Dutch glass-decoration, however, consisted in scratching and dotting with the diamond. Throughout the I 7th century scratching with the diamond was a popular method; dilettante artists, like the three sisters Roemers and Willem J. van Heermskerk, adorned glasses and bottles with beautiful sinuous calligraphy (q.v.). In the 18th century scratching was superseded by dotting or "stippling," in which process the entire design is composed of small dots hammered into the surface of the glass with a diamond-point (Plate VI., No. I I). The greatest masters of this airy and delicate decoration, to the success of which the clear, faultless English flint-glass was essential, are Frans Greenwood of Dordrecht (d. 1761 or 1762) and D. Wolff of The Hague (d. 1809).