Golf in France and Elsewhere

GOLF IN FRANCE AND ELSEWHERE Before coming to British golf, something must be said of that in other countries. As long ago as 1907, Arnaud Massy, originally a Biarritz fisherman, won the British open championship. He has never repeated that feat, though he tied with Vardon in 191 i and has several times beaten strong fields of British players in the French championship and did so once again in 1925. There has been no other French professional as good as Massy, but there has been a number of very good ones, such as the late Louis Tellier, Gassiat, Laffitte, Dauge, and one most remarkable one armed player, Yves Bocatzou. The French amateurs have hardly yet reached the same standard, but France has produced one ex tremely good lady player, Mlle. Simone de la Chaume. She is already a very fine player, and in 1927 won the British ladies' championship, though it should be added that neither Miss Wethered nor Miss Leitch was competing.

There are to-day some very good courses in France. Paris has La Boulie, Chantilly, St. Cloud, and Fontainebleau. Le Touquet, near Etaples, is excellent, a mixture of seaside sand and inland pine trees; and Wimereux, lately remodelled, promises well. In the Riviera English visitors have made courses of varying quality. Cannes has one very pleasant one among pine trees at Napoules and the new Cannes country club, rather farther off at Mougins, is probably better. Sospel, in a mountain valley above Mentone, is very charming, and others that are at least pretty and worth playing on are Costebelle, Valescure, and Cagnes, near Nice. On the Cote d'Argent there is La Nivelle, near St. Jean de Luz, where Massy is the professional, and Biarritz. Moreover, close to Biar ritz there is a new course, Chiberta, which, if time and the blazing sun are kind to it, should be a course of a higher class than any of those mentioned. Nor must Pau be forgotten. It is a club of now almost venerable age, one of the oldest out of Scotland. The golf is good and interesting and, what is more, can be played in reasonable peace and quiet. Switzerland and Italy have courses which are at least very beautiful. Canada, if it has not yet quite attained to the American standard of skill, is almost as keen and spends almost as much money on its courses and club houses. Australia has some good courses, notably perhaps Seaton, near Adelaide, and Kensington, near Sydney ; and it has bred at least one first-class professional, Joseph Kirkwood, who has several times done well in the British open championship and is now one of the leading professionals in America.

Japan has taken to the game with enthusiasm, although the turf of the country is not of the best kind. It possesses a golf paper, Gol f do m, and has some good players, although none has yet reached the standard of its lawn-tennis players. In short , in its world-wide character the game is only second to lawn tennis.

In Great Britain golf has become steadily more and more popu lar, and nowhere more markedly than in its original home, Scot land. There, it is essentially the people's game, and there are many municipal courses on which it can be played at the minimum of expense. In England, it is still largely the game of the compara tively well-to-do, but municipal golf is on the increase, and wherever it arises it is an instant success, as witness the public course in Richmond Park, which is crowded with all sorts and conditions of players. There are to-day far more golfers than there used to be who have begun the game as boys. It is not a school game but many boys play in their holidays; and, con sidering this fact, it is rather surprising that Great Britain does not breed more good young players. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge are full of golfers, but only a few of them are really good and the standard of university teams is not noticeably higher than it used to be. The number of players who may fairly be called good has of course increased greatly throughout the country and championship fields have correspondingly increased.

British Amateurs.

It has already been said that when the game was resumed after the World War the leading British pro fessionals were a little past their best. Much the same may be said as regards the amateurs. Mr. John Ball, Mr. Hilton, and others of their generation had naturally begun to think of retiring and their places were left open. Two very brilliant young players, too young to be heard of before the war, at once made their presence felt after it, Mr. Cyril Tolley and Mr. Roger Wethered. Of all British golfers in late years, these two have been the most essentially dramatic, and have taken the largest share of public attention. Both can hit the ball enormous distances, both are on their day almost unapproachably good and both can be, on an off day, dis appointing. They lack the consistency of such a player as Mr. John Ball, but the game as played by them is an exciting and at tractive one. Each has won the amateur championship once. Mr. Tolley has won the French open championship against a strong field, and Mr. Wethered did the best thing which any British amateur has done for a long time when he tied for the open cham pionship with Jock Hutchison.A golfer of a rather different type, Sir Ernest Holderness, has twice won the amateur championship since the war and, though he has not the magnetic powers of a Tolley or a Wethered, he is beyond doubt a very fine player. In the matter of consistency and steadiness he challenges comparison with the best of the older amateurs. In 1925 another eminently consistent player, Mr. Robert Harris, won the amateur championship. It was a most popular victory, for Mr. Harris has now been among the leading amateurs for a long time ; he was in the semi-final of the amateur championship as long ago as 19o7 and in the final in 1913 and 1923. In 1026, Mr. Sweetser, the American, won. The year 1027 saw no American invasion but produced a new and entirely worthy champion in Dr. Yweddell of Stourbridge who, though an Eng lishman, learnt much of his golf in Scotland. He is an extremely sound and painstaking golfer and his victory will probably be good for golf because he is a player who is essentially straight and accurate. There is some danger lest too much importance should be attached to length and young golfers should indulge in an orgy of slogging. On the whole the amateur standard is going up; but there is still room for a combination of the older and younger virtues.

British Professionals.

No one or two professionals have definitely succeeded to the throne left vacant by the "triumvirate" —Vardon, Braid, and Taylor. Duncan appeared likely to do so when he played so wonderfully well in 1920, but he has since been power of rising superior to circumstances, which Hagen so con spicuously possesses. The two Whitcombes, George Gadd, Ocken den, Havers, and many others all play exceedingly well without quite rising to the greatest heights. In 1925, however, there ap peared suddenly another player, Compston, who adds great de termination and character to great physical strength and may possibly be the man for whom the British golfing world has been waiting. He was unquestionably the player of the year and appears, far from relaxing his efforts after a victory, to go from strength to strength. Late in the year he was defeated by Abe Mitchell, who played golf of overpowering brilliancy, but this did not discourage him, after seeming to go back for a while, he played perhaps the best golf of his life towards the end of 1927.

Golf for Ladies.

In its ladies' golf Great Britain is strongest. For the first few years after the war Miss Cecil Leitch was the outstanding figure. She has all the qualities of a great player; it is possible to criticize her rather unorthodox methods, but not their results. She is still as good as ever, but she has been sur passed by Miss Joyce Wethered, who to equal strength and cour age adds a sounder method. Indeed, she is so sound in everything she does that it is impossible to suggest even the smallest loophole in her armour. She won the English close championship five times in succession and the open championship three times in four years, the last time after a terrific struggle with Miss Leitch, in which both played superbly. She has now no worlds left to conquer and has, for a while at any rate, retired from public competition. Miss Leitch has also not played quite so regularly in championships; but these two long continued to dominate ladies' golf.Glossary of Technical Terms Used in the Game Ace —A hole scored in one stroke.

Addressing the oneself in position to strike the ball. All Square.—Term used to express that the score stands level, neither side being a hole up.

Approaching.—Playing or attempting to play a ball on to the putting green.

player whose ball lies furthest from the hole is said to be away.

Back spin.—Rotating of the ball in flight backward, imparted by causing the clubhead to strike the ball a descending blow, as in a draw shot in billiards.

Ba ff .—T o strike the ground with the club when playing, and so loft the ball unduly.

Baffy.—A short wooden club, with laid-back face, for lofting shots. Bent.—Rushes. Also a certain species of grass of fine texture used for putting greens.

Best-Ball Match.—A match in which a single player competes against the better ball of two others.

Birdie.—A hole scored in a stroke less than par.

Bisque.—A handicap stroke given under the condition that the player may use it at his option on any hole, but with the provision that he must announce his choice to do so on any hole, before striking off from the tee for the next hole.

Bogey.—The number of strokes which a good average player should take to each hole. This imaginary player is usually known as "Colonel Bogey" and plays a fine game.

Bone.—A piece of horn, wood fibre, or hard composition placed in the sole of the club at its front edges to protect it from injury.

Borrow.—In putting to play to the right or left of the direct line from ball to the hole in order to compensate for roll or slant in the putting green.

Brassy.—A wooden club with a brass sole.

Bulger.—A driver in which the face "bulges" into a convex shape. The head is shorter than in the older-fashioned driver.

Bunker.—A sand-pit, either natural or artificial, preferably the former. The word is loosely used also for any hollow (in which a club may not be grounded) devised to endanger the approach to the hole.

Bye. The holes remaining after one side has become more holes up than remain for play.

Caddie.—The person who carries the clubs. Diminutive of "cad"; (from Fr. cadet, cf. laddie) .

Carry.—The distance between where a ball is hit and where it first strikes the ground.

Cleek.—The iron-headed club that is capable of the farthest drive of any of the clubs with iron heads.

Club.—The implement with which the ball is struck.

Cop.—The top or parapet of a bunker.

Course.—The terrain over which the game is played. All ground on which play is permitted, including fairway, rough, hazards and putting greens. See also Links.

Cup.—A depression in the ground causing the ball to lie badly. Guppy.—Referring to the position of the ball, a small depression in the ground, as a Guppy lie.

Dead.—A ball is said to be "dead" when so near the hole that the putting it in in the next stroke is a "dead" certainty. A ball is said to "fall dead" when it pitches with hardly any run.

Divot.—A piece of turf cut out in the act of playing, which, be it noted, should always be replaced before the player moves on. Dormy.—One side is said to be "dormy" when it is as many holes to the good as remain to be played—so that it cannot be beaten.

Draw.—An effect of making the ball curve or veer to the left. See also Hook and Pull.

Driver.—The longest driving club, used when the ball lies very well and a long shot is needed.

Driving Iron.—An iron club with little loft ; similar to the cleek, but having a slightly shorter and thicker blade.

Eagle.—A hole scored in two less than par.

Face.—The surface of the club with which the ball is struck. Fairway.—The expanse of ground, extending in whole or in part from the tee to the putting green, especially prepared for play with excellent turf on which the grass is kept cut.

Flat.—Referred to the club, as a "flat lie," means that the angle between the sole of the club and the shaft is decidedly obtuse. Follow Through.—The continuation of the sweep of the club after the ball has been struck.

Foozle.

Any very badly missed or bungled stroke.

"Fore!.

A cry of warning to people in front.Fourball Match.—A match in which two players to a side are engaged, each playing his own ball.

Foursome.—A match in which four persons engage with two balls, two on each side playing alternately with the same ball. A four-ball match implies that each of the four players uses his own ball only, and they may all play against each other or may play in pairs, the best ball of each pair scoring.

Gobble.—Said of a boldly hit putt, which finds the hole, but which must have gone considerably beyond the hole, had it failed to go in. Green.—(a) The links as a whole ; (b) the "putting-greens" around the holes.

Grip.—(a) The part of the club-shaft which is held in the hands while playing ; (b) the grasp itself—e.g. "a firm grip," "a loose grip," are common expressions.

Half.—An expression used to indicate a handicap allowance, meaning a stroke on every other hole ; also one used to indicate that two players scored alike on a hole.

Half-Shot.—A shot played with something less than a full swing. Halved.—A hole is "halved" when both sides have played it in the same number of strokes. A round is "halved" when each side has won and lost the same number of holes.

Handicap.—The strokes which a player received either in match play or competition.

Hanging.—Said of a ball that lies on a slope inclining downwards in regard to the direction in which it is wished to drive.

Hazard.—Limited space or area in which the privileges of play are restricted, including bunkers, water courses, ponds, sand, etc. ; also recognized roadways and paths.

Head.—The knob or crook part of the club as distinguished from the shaft or handle. Heads are made of wood, iron, and sometimes metallic compounds.

Heel.—To hit the ball on the "heel" of the club, i.e. the part of the face nearest the shaft, and so send the ball to the right, with the same result as from a slice.

Hole.—The circular opening in the ground into which the ball is played, being 4a in. in diameter and 4 in. deep; also a unit of play including teeing ground, putting green and all intermediate ground.

Hole-out.

To make the final stroke in playing the ball into the hole.Honour.—The privilege (which its holder is not at liberty to decline) of striking off first from the tee.

Hook.—To cause the ball to swerve to the left of its original line of flight.

Hose or Hosel.—The socket on iron clubs into which the shaft is fitted.

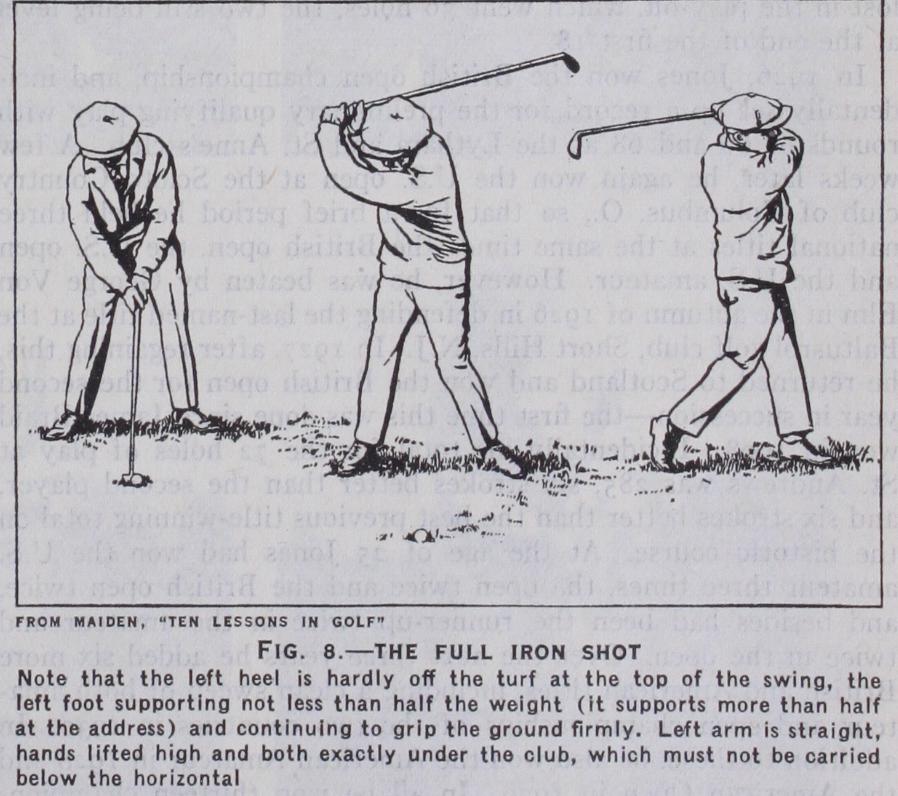

Iron.—An iron-headed club intermediate between the cleek and lofting mashie. There are driving irons and lofting irons according to the purposes for which they are intended.

Jigger.—An iron club with narrow blade, in classification intermediate between a midiron and a mashie.

Lie.

(a) The angle of the club-head with the shaft (e.g. a "flat lie," "an upright lie,") ; (b) the position of the ball on the ground (e.g. a "good lie," "a bad lie") .Like, The.—The stroke which makes the player's score equal to his opponent's in course of playing a hole.

Like-as-we-Lie.—Said when both sides have played the same num ber of strokes.

Line.—The direction in which the hole towards which the player is progressing lies with reference to the present position of his ball.

Links.—Ground on which golf is played; more properly used of a seaside course.

Loft.—The angle of declination from 9o° on the face of a club ; also to hit the ball on a high short trajectory, usually over some intervening obstacle.

Lo f t er.—An iron club with considerable loft on the face, for lofting the ball.

Long Game.—The strokes where distance is an important factor, as distinguished from play where control of distance is a problem.

Loose Impediments.—Any detached object lying in the immediate vicinity of the ball, not fixed in the earth.

Mashie.—An iron club with a short head. The lofting mashie has the blade much laid back, for playing a short lofting shot. The driving mashie has the blade less laid back, and is used for longer, less lofted shots.

Mashie-Iron.—A heavy mashie with a somewhat longer shaft than the mashie.

Mashie-Niblick.—An intermediate iron club between the mashie and niblick.

Match-Play.—Play in which score is reckoned by holes won and lost. Medal-Play.—Play in which the score is reckoned by the total of strokes taken on the round.

Midiron.—An iron head club for medium distances, having less loft than a cleek or driving iron, and more than a mashie.

Mid-Mashie.—A deep-face mashie with a slightly longer shaft than a mashie.

Nassau.—A basis of scoring, in which three points are involved, one on the first nine holes, one on the second nine, and one on the full eiehteen.

Neck.—The bent or crooked part of the club where the shaft joins on to the head.

Niblick.—A short stiff club with a short, laid back, iron head, used for getting the ball out of a very bad lie.

Number One. —A late tendency to number iron clubs rates them as follows: Number one, driving iron ; number two, midiron ; number three, mid-mashie or mashie-iron ; number four, mashie ; number five, mashie-niblick ; number six, niblick.

Nose.

The outward point of the club face ; called also the toe.

Odd, The.

A stroke more than the opponent has played.Par.—Theoretically perfect play, calculated on the number of strokes required to reach the green, plus two putts. Distance is the chief fac tor in determining the par for a hole. Following are the divisions: all distances up to 25o yds., par 3; 251 to 445, Par 4 ; 446 to 600, par 5 ; over 600, par 6.

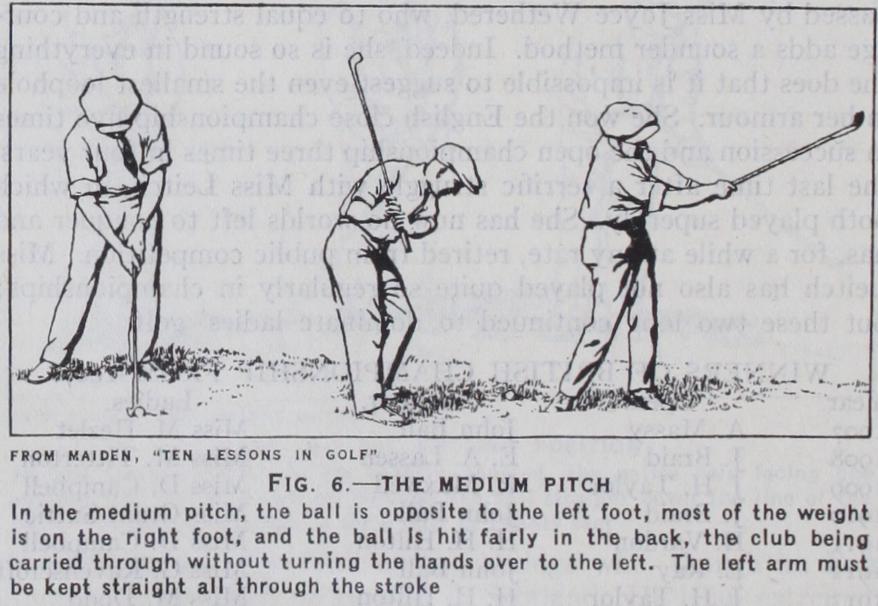

Pitch.

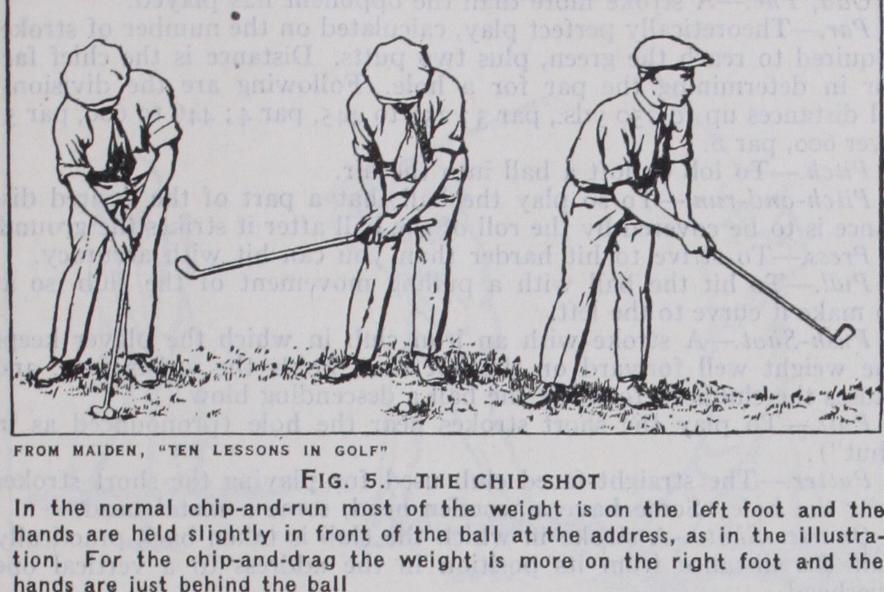

To lob or loft a ball into the air.Pitch-and-run.—To so play the ball that a part of the desired dis tance is to be covered by the roll of the ball after it strikes the ground. Press.—To strive to hit harder than you can hit with accuracy. Pull.—To hit the ball with a pulling movement of the club, so as to make it curve to the left.

Push-Shot.—A stroke with an iron club in which the player keeps the weight well forward on the left foot, holds the wrists firm, and causes the clubhead to strike the ball a descending blow.

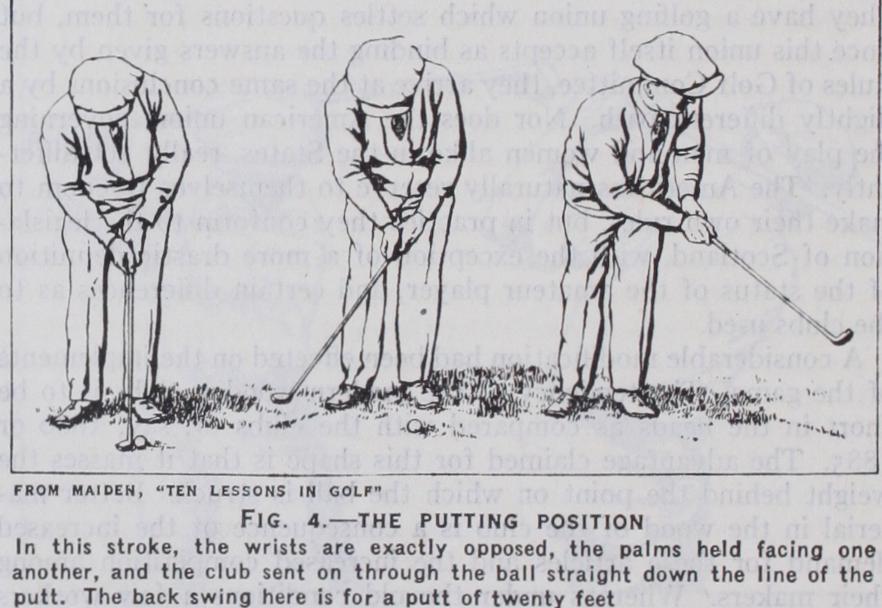

Putt.—To play the short strokes near the hole (pronounced as in "but") .

Putter.—The straight-faced club used for playing the short strokes near the hole. Some have a wooden head, some a metal head.

Quarter-Shot.—A stroke in which the club is taken back practically half the distance from its position in the address to a vertical one overhead.

Rough.—Ground to left and right of the fairway ; also at times inter vening between the tee and fairway, on which vegetation is allowed to grow without being cut ; long grass and weeds.

Rub-of-the-Green.—Any chance deflection that the ball receives as it goes along.

Run.—The distance the ball rolls after striking the ground.

Run Up.—To send the ball low and close to the ground in approach ing the hole—opposite to lofting it up.

Scare.—That portion of wood clubs where the head and shaft are spliced together, the union being bound by closely wound thread or cord.

Sclaff.—To strike the ground back of the ball before striking it. Scratch Player.—Player who receives no odds in handicap com petitions.

Scruff.—To cut just through the roots of the grass in playing the ball. Shaft.—The handle of the club, as distinguished from the head. Short Game.—Approach shots and putts.

Single.

A match between two players.Slice.—To hit the ball with a cut across it, so that it flies curving to the right ; also the flight of ball so struck.

Socket.—The opening in the neck of an iron club into which the shaft is fitted ; also to hit the ball back on this part of the club, or the heel.

Sole.—The bottom of the club on which it rests when set in position on the ground.

Spoon.—A wooden head club with considerable loft and a shaft shorter than the driver or brassie.

Spring.

The resilience in the shaft of a club.Square.—Said of a match, when the players are even.

Stance.—The position of the player's feet in hitting the ball. Stances are designated as open, square and closed. In the square stance, the toes of the feet are in a line parallel with the proposed line of play. In the open stance, the left foot is drawn back from the line. In the closed stance, this foot is advanced beyond the line.

Stroke.

The hitting or trying to hit the ball. A forward movement of the club made with the intent to hit the ball, even though the ball is not struck, constitutes a stroke.Swing.—The sweep of the club in the operation of hitting the ball. Tee.—The little mound of sand on which the ball is generally placed for the first drive to each hole.

Teeing-Ground.—The place marked as the limit, outside of which it is not permitted to drive the ball off. This marked-out ground is also sometimes called "the tee." Third.—An expression in handicapping, meaning that one of the players is allowed a stroke on one-third of the holes, or six strokes in 18 holes.

Three-Quarter Swing.—A stroke in which the club on the back-swing is carried back approximately half-way between a vertical position and a horizontal one back of the head.

Three-Ball Match.—A match in which three players compete against the other, each playing his own ball.

Three-Some.—A match in which one player competes against two others of a side, the two playing alternate strokes with the same ball. Through-the-Green.—Conditions governing play from the time the ball is played from the tee until it reaches the green, except in hazards. Through-the-green covers play both in fairway and in the rough.

Toe.—The outward point of the head of the club ; also called nose. Top.—To hit the ball above the centre, so that it does not rise much from the ground.

Under-Cut.—Also called "cut" ; same as Back Spin.

Up.-A player is said to be "one up," `two up," etc., when he is so many holes to the good of his opponent.

Upright.—Referring to the lie of clubs, means that the angle between the head of the club and the shaft is less obtuse than in a flat lie. Whipping.—The thread or twine used in wrapping the space where the head and shaft of the club are joined together.

Wrist-Shot.—A shot less in length than a half-shot, but longer than a putt. (I. BN. ; H. G. H. ; B. D.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J. Kerr, Golf Book of East Lothian (1896) ; W. E. Bibliography.-J. Kerr, Golf Book of East Lothian (1896) ; W. E. Hughes, Chronicle of Blackheath Golfers (1897) ; R. Clark, Golf: A Royal and Ancient Game (1899) ; H. J. Whigham, The Book of Golf and Golfers (5899) ; H. G. Hutchinson, Hints on Golf (19o3) ; G. W. Beldam, Great Golfers: their Methods at a glance (1904) ; J. Braid, Advanced Golf (1908) ; A. Massy, Le Golf (i9i i) ; J. H. Taylor, Taylor on Golf (1911) ; H. G. Hutchinson, The New Book of Golf (1912) ; Fifty Years of Golf (1919) ; J. D. Travers, A Golf Book (1913) ; J. W. Duncan and B. A. Clark, Municipal Golf (Seattle, 1917) ; J. M. Barnes, Picture Analysis of Golf Strokes (1919) ; A Guide to Good Golf (1925) ; H. S. Colt and C. H. Alison, Some Essays on Golf Course Architecture (1920) ; B. Darwin, Golf: Some Hints and Suggestions (1920) ; A Friendly Round (1922) ; The Golf Courses of Great Britain (1925) ; C. Evans, Chick Evans' Golf Book (1921) ; A. Kirkaldy, Fifty Years of Golf (1921) ; F. Ouimet, Golf Facts for Young People (1921) ; J. White, Putting (1921) ; Easier Golf (1924) ; Cecil Leitch, Golf, etc. (1922) ; H. H. Hilton, Modern Golf (1922) ; R. and J. Wethered, Golf from Two Sides (1922) ; G. W. Beldam, The World's Champion Golfers (1924) ; G. Duncan and B. Darwin, Present Day Golf (1924) ; G. Sarazen, Common Sense Golf Tips (1924) ; R. E. Howard, Lessons from Great Golfers (1924) ; C. J. H. Tolley, The Modern Golfer (1924) ; H. Vardon, How to Play Golf (1924) ; Abe Mitchell, The Essentials of Golf (1926) ; Robert Hunter, The Links (1926) ; Robert T. Jones, jun., and O. B. Keeler, Down the Fairway (1927) ; see also the volume on Golf in the Badminton Library, The Golfers' Yearbook, The Golfing Annual, and the Amer ican Annual Golf Guide and Yearbook. (H. G. H.; B. D.) Golf first began to attract serious attention in the United States sometime during the early and middle '8os when such pioneers as Charles B. MacDonald, Robert Lockhart, T. A. Bell and George Wright carried clubs and balls into the country. The early history of golf in the United States is shrouded in a fog of doubt. Out of this fog two facts seem well established. One is that the first actual bona fide golf club, organized as such, was the St. Andrews golf club of Yonkers, N.Y., which in 1888 constructed and played over a six-hole course. The other is that the Chicago golf club was the first to construct a full 18 hole course. This club, whose course was designed and constructed by Charles B. MacDonald, had 18 holes ready for play at Wheaton, Ill., in 1893. In the late '8os J. Hamilton Gillespie, a young Scotchman heading a land syndicate, made a start at Sarasota, Fla., and about the same time T. A. Bell laid out four holes on a farm belonging to his father in what is now a part of the city of Burlington, Ia. Bell claims to have been the first man to carry golf clubs into the United States. The first competition which assumed the nature of a national championship was played at the Newport (R.I.) golf club, on Sept. 1894. It was a stroke play competition over 36 holes and was won by W. G. Lawrence with a total of 188 strokes, Charles B. MacDonald finishing second with 189. In October of the same year a match play meeting was held at the St. Andrews golf club. It was won by L. B. Stoddart, who defeated MacDonald by one hole in the final match. Before the season of 1895 opened, the U.S. Golf Association was formed and held the first formal championship at the Newport golf club in October of that year. It was won by MacDonald, who defeated C. E. Sands of St. Andrews in the final match. Five clubs up the charter members of the association. They were the Newport golf club, Newport, R.I., the Shinnecock Hills golf club, Southampton, L.I., the Country club, Brookline, Mass., St. Andrews golf club and the Chicago golf club.

The year 1895 also saw the first open championship as well as the first championship for women. The former was held at the Newport golf club at 36 holes. It was won by Horace Rawlins with a total of 173 strokes. The women's championship was played at the Meadowbrook club, L.I., and was won by Mrs. C. S. Brown, who scored 132 for the 18 holes. It is further noteworthy that 1895 saw a marked growth in the number of golf clubs in the country. From about 4o at the beginning of the year the number had increased to more than ioo by the end.

Growth of the Game.

Naturally enough, in the early days of the game its leading exponents both in administration and playing skill were men and women who had first taken to it in the British Isles. For several years players so trained were the successful competitors for championship honours both among amateurs and professionals. But by 190o Walter J. Travis, who developed his game in the United States, though an Australian by birth, suc ceeded in winning the amateur championship. He repeated this triumph in 1901 and 1903, and since that time only twice have foreign-born players won the title, Harold H. Hilton of England winning at the Apawamis club of Rye, N. Y., in 1911 and C. Ross Somerville of London, Ontario winning at the Baltimore Country Club in 1932. In professional circles, a longer period was re quired to develop a native-born champion. The first instructors were mostly Scots with a few English, and these dominated the open championship until 1912, when John J. McDermott became the first American-born player to win the open championship.Meantime, as far back as 1904, Walter J. Travis had won the British amateur championship at Sandwich. McDermott's vic tory in 1912 marked another step, and the following year another event took place entitled to rank with the performance of Travis. This was the victory of Francis Ouimet, a 2o-year-old amateur, in the open championship. Travis's victory at Sandwich had pro vided a big stimulus to the growth of the game, but Ouimet's performance added still greater impetus, and the game took on a big expansion. Its growth was moving by leaps and bounds until the entry of the United States into the World War checked it temporarily. But not, however, until Robert T. Jones, familiarly known throughout the golfing world as "Bobby," made his first entry.

At the age of 14 Jones entered his first amateur championship at the Merion cricket club in 1916. A preliminary qualifying test of 36 holes was played before match play was begun. On the first 18 holes, he led the entire field. His showing on the second round was not so flattering, but he qualified easily, and won his first two matches. His opponent in the second of these was Eben M. Byers, who had held the title in 1906. When beaten in the third match, he bowed to none other than Robert A. Gardner, the defending champion. Eight years later Jones returned to Merion to win his first amateur title. A year previous, he had won the open championship at the Inwood Country club in Long Island, and had finished second in defending this title at the Oakland Hills Country club of Detroit, earlier in the summer, before his triumph at Merion. He again won the amateur in 1925, and also tied for the open with Willie Macfarlane, a Scottish-born professional, but lost in the play-off, which went 36 holes, the two still being level at the end of the first 18.

In 1926, Jones won the British open championship, and inci dentally set up a record for the preliminary qualifying play with rounds of 66 and 68 at the Lytham and St. Anne's club. A few weeks later, he again won the U.S. open at the Scioto Country club of Columbus, O., so that for a brief period he held three national titles at the same time : the British open, the U.S. open and the U.S. amateur. However, he was beaten by George Von Elm in the autumn of 1926 in defending the last-named title at the Baltusrol golf club, Short Hills, N. J. In 1927, after regaining this, he returned to Scotland and won the British open for the second year in succession—the first time this was done since James Braid won in 1908. Incidentally his total for the 72 holes of play at St. Andrews was 285, six strokes better than the second player, and six strokes better than the best previous title-winning total on the historic course. At the age of 25 Jones had won the U.S. amateur three times, the open twice and the British open twice, and besides had been the runner-up twice in the amateur and twice in the open. Over the next three years he added six more British and American titles, including a clean sweep of both ama teur and open championships of the two countries in 193o. In addition to these, he also won the American Amateur in 1928 and the American Open in 1929. In all he won thirteen champion ships of the two countries in a period of eight years beginning in 1923.

Another American amateur, W. Lawson Little, son of an officer in the U.S. army, who got his first introduction to golf while his father was stationed at Shanghai on a course where graves supplied a part of the hazards of the course, established another amazing record by winning both the British and American amateur championships in 1934 and repeating in the two events in Owing to the World War there were no national championships during 1917-18, though certain other lesser championships were held. But beginning in 1919, the national events were resumed, and with this resumption came still another very extensive growth of the game and a marked advance in the level of play judged on an international basis.

Municipal Golf.

One of the most marked developments in golf in the United States has been in municipal and public courses. The first of these was opened at Van Cortlandt Park, N.Y., in 1895. In 1935 more than 25o cities were operating over 30o such courses, and there were half as many more proprietary courses, operated on daily fee, or pay-as-you-play, plans. Figures available on about one-half of the actual public courses show that approxi mately 7,000,00o rounds were played on these during the year.Apart from its influence on the competitive aspects of golf in an international way, the United States has contributed one very important factor to the development of the game generally—the rubber-cored ball. This was the invention of Mr. Coburn Haskell, who first conceived the idea in the summer of 1898, but it was more than two years before it began to attract any considerable attention, and it was not until 1902, when Alex Herd, Scotch professional, won the British open championship, that the new ball scored its first triumph in a major championship. Since that time it has become the medium of play throughout the world.

Introduction of the tubular steel shaft for golf clubs is also a development of the U.S. game. These were legalized by the United States Golf Association April 12, 1924, and by the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews November 28, 1929. (G. R.)