Tion

TION) .

Occurrence and Distribution of Gold.

Gold occurs in mi nute quantities in almost all rocks. Igneous and metamorphic rocks contain more than sedimentary deposits which have doubtless de rived it from the sea. In sea-water the amount of gold present appears to vary from 0.03 grain to I grain (2 to 6o mg.) per ton, but all attempts to extract it at a profit have failed. It exists in all copper and lead ores. It is everywhere, apparently even in vegetation, for there is gold in the coal of the Cambrian coalfield of Wyoming and a rich deposit in a bed of lignite in Japan.Disseminations throughout large masses of rock, rich enough to be called ores, are unusual and gold is generally obtained from quartz lodes or veins, or from deposits derived from them by denudation, e.g., river gravels and the "banket" or conglomerate of the Transvaal. The gold is not evenly distributed in the lodes but is concentrated in certain parts. Many lodes are barren, especially those which do not contain pyrites or other sulphides. The reason why gold occurs in greater quantities in lodes than in the neighbouring rocks is not known with certainty but it is considered that it has risen from below with other minerals, partly at least in solution in hot water, and has been precipitated where it is found. The mineral most commonly found with gold in lodes is iron pyrites, a yellow sulphide of iron. Others are copper pyrites, arsenical pyrites, zinc blende and stibnite—all sul phides. At the surface of the ground, where the lodes are weathered, limonite, a yellow oxide of iron, is the best indicator of gold. In alluvial deposits ("placers") magnetite ("black iron sand") usually occurs. No mineral, however, is an infallible guide to gold, except perhaps in particular localities.

The gold in ores is generally free or native, not combined with other elements to form chemical compounds except in the tellu rides. Even the gold contained in iron pyrites is metallic, consist ing of thin films coating the crystals or perhaps the cleavage planes of the pyrites. Gold in ore is generally invisible unless magnified, but sometimes occurs in crystalline grains or arborescent flakes which can be seen, and more rarely gold is found in considerable masses. Large crystals of an inch or more across have been found in alluvial deposits in California. They belong to the cubic system and are usually in the form of octahedra or rhombic dodecahedra. In Transylvania gold occurs in thin plates and in some other districts in wire form. Tellurides of gold are contained in rich ores in Western Australia and Colorado and occur elsewhere. The mineral calaverite, a bronze-yellow gold telluride, contains 4o% of gold, and sylvanite or graphic tellurium, a steel-grey mineral, contains up to 28% of gold combined with some silver. The tellu rides are often grey or blackish. Tellurium is removed from tellu ride ores by weathering and finely divided yellow amorphous gold or "mustard gold" is left. It resembles yellow clay, but can be made bright by burnishing. .It occurs in yellow splashes at Kal goorlie. The rocks through which auriferous veins pass are generally metamorphic, such as slates or schists, with volcanic rocks in the neighbourhood. Andesite, a volcanic rock, is often found in gold districts. Alluvial deposits or "placers" have been the most prolific sources of gold in the past, although by 1927 they had become of little importance. They are the sands, gravels and detritus of ancient or existing streams and have been derived from the disintegration of auriferous veins or rocks. The gold occurs as "gold dust," which consists of small scales and rounded grains, and "nuggets" or larger masses of a rounded or mammilated form. The largest nugget ever found was the "Welcome Stranger," 2,52o oz. in weight, which was found in I 86g in Victoria in a rut made by a cart, only a few inches below the surface of the ground.

Among the most productive goldfields in ancient times were those in Egypt, where in the deep mines the enslaved labourers were cruelly maltreated, and in Asia Minor where flows the river Pactolus, the source of the riches of Croesus. The Romans ob tained their gold in great part from Transylvania, still a goldfield. After the discovery of America the main supplies to Europe came from there. In I 850-6o the gold diggings of California and Australia were at their zenith and at the end of the I gth century the "placers" of Klondike and Alaska, the last-named a beach deposit, were famous for a short time. By 1927 the Transvaal had been for many years the richest goldfield in the world but there are important goldfields in every continent and in many countries (see PHYSICAL RESOURCES, Precious Metals Group). The geological age of the deposits in which gold is found ranges from Archaean to Quaternary but is mainly very ancient or compara tively recent. The series of rocks formed between these eras contain little gold.

Placer Mining and Prospecting.

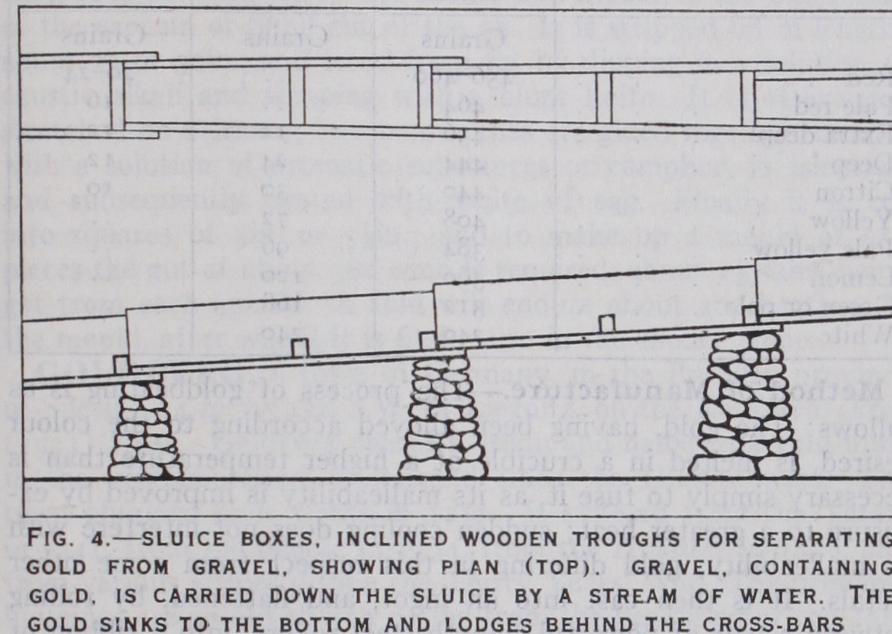

Gold sands and gravels occur in the beds of most rivers which flow for part of their course through a region composed of crystalline rocks. The gold may be dispersed through the sand or caught in the crevices of the rocky bed of the river and covered by sand. Sometimes the auriferous sands are covered by thick beds of barren detritus or even lava flows and can be reached only by sinking shafts or driving tunnels. The mining operations are usually simple. In Siberia, Alaska and the Yukon the gravels are perennially frozen and are thawed with steam jets or wood fires. The sand is tested by panning. The "dirt" is stirred and shaken with water in a pan (fig. I.) to enable the gold to settle to the bottom, and the upper portions are gradually washed away by dipping the pan into water and pouring it off until only the gold and heavy minerals are left. Finally the gold is separated by a series of dexterous twists and tilts. The "batea" (fig. 2), a shallow wooden cone, is used instead of the pan in South America and by negro miners. If the deposit is found to be rich enough to work it is treated in pans or cradles or sluice boxes. Work with the pan is simply a repetition of the testing process already mentioned. In the Klondike a single pan of earth sometimes yielded 15 oz. of gold, but that was exceptional and work on so small a scale Teas seldom paid expenses. The "cradle" or "rocker" (fig. 3), which sembles a child's cradle, deals with larger quantities of earth and is more profitable. The gravel is shovelled on to the perforated iron plate, and water is poured on. The fine material drops through on to the apron, which is then carried forward over the sloping floor, rocking being continuous. The gold is caught by the "riffles," which may be strips of wood. A riffle or riffle bar is almost anything which will break the current of water and provide a protected spot where gold can settle and remain disturbed. Mercury is often placed in riffles to amalgamate the gold (see AMALGAMATION). Thousands of improved cradles were in use at Nome in Alaska as recently as I goo. A "sluice box" (fig. 4) is an inclined wooden trough through which gravel is washed by a stream of water. The troughs are fitted together to form a sluice which may be hundreds of yards long. If gold is still being caught at the lower end of the sluice, more boxes are added, but most of the gold is caught in fles near the upper end, where the gravel is shovelled in and mercury sprinkled. In California thick beds of gravel on hill-sides in the gulches have been worked by hydraulic mining. Powerful jets of water break down the banks of gravel and wash the material through a line of sluices without hand labour. The work was sometimes on a very large scale requiring huge reservoirs as for a great city, with many miles of pipes and flumes. The nozzle for the jet was increased to I fin. in diameter with a pressure of water given by a head of 2ooft. The cost of treatment was only a few cents per cubic yard and poor ground could be treated at a profit. Millions of tons of sand were washed down and delivered as "tailings" into the Yuba and Feather rivers, and the effects on farming lower down were so marked that an injunction was obtained against the hydraulic miners in 188o and their work thereafter was strictly limited.In the period 1900-15 dredging became the most important branch of placer working. The chain-bucket dredger was in gen eral use. It is similar to those used in harbours, having a number of buckets attached to an endless moving chain. The gravel is scooped up from river beds and delivered on the deck of the vessel, where it is washed. It is disintegrated in revolving screens and then flows over gold-saving • tables furnished with riffles, or through short sluices. The tailings pour overboard at the stern or are deprived of the water in them by being run on to sieves and are then stacked on the river bank by a bucket elevator. Dredging originated in New Zealand and attained its greatest popularity on the rivers there, and in California. "Paddock dredging," a later development in western America, enabled all flat placer ground to be treated, even if not in or near river beds. The dredger is placed in a reservoir filled with water, the gravel is dug away from one end of the reservoir, the gold is washed out, and the tailings are stacked at the other end. In this way the dredger moves across country taking the reservoir with it. By piling gravel round the reservoir and letting in more water the dredger can be made to work its way uphill. The cost of dredging before the World War wa: only about 2d. or 3d. per cubic yard of gravel, not counting the capital expenditure, so that poor material could be treated at a profit, but in 1926 comparatively few dredgers remained at work.

Vein Mining and Ore Treatment.

Methods of exploration and mining of veins do not greatly differ from those in use on the deposits of other metals (see MINING, METALLIFEROUS). Gold ore raised to the surface is treated by amalgamation or by the cyanide process (q.v.). Before the invention of the cyanide process, the tailings from amalgamation mills were often concen trated on sloping tables, or in troughs lined with blanketing or by other machines. The concentrates consisted chiefly of sul phides, especially pyrites, and of ten contained 2 or 3 oz. of gold per ton. They were treated by smelting and in some places by chlorination, an obsolete process. Gold ores which cannot be treated by amalgamation or cyaniding are smelted with copper or lead ores (see COPPER and LEAD) . The gold is found in the metal lic copper or lead which is tapped out from the furnaces and is recovered in the electrolytic refining of the copper and the de silverizing of the lead. The amount of gold produced in the world by smelting is comparatively small.

Refining.

Gold bars produced at the mines and gold dust and nuggets from placers are impure, containing as a rough aver age about 9o% gold with 8-9% of silver and smaller quantities of other metals. The gold is often brittle and is refined to make it suitable for minting or for use in the industries. The ancients refined gold by "cementation." Plates of gold were stacked in an earthen pot, and were surrounded and separated by powdered porous stone or brickdust, mixed with common salt and sulphate of iron. The pot was covered and heated to redness, but the temperature was not high enough to melt the gold. The silver and other impurities in the gold were gradually converted into ides, which melted and oozed out of the gold and were absorbed by the biickdust, and the gold was purified. Nitric acid was in use for refining gold in the 16th century. The gold was melted with three times its weight of silver (process of "inquartation"), and granulated by pouring into water. The granules were boiled in nitric acid which dissolved the silver and left the gold changed. If the alloy of gold and silver contains more than 33% gold, part of the silver remains undissolved, and it is for that reason that the excess of silver is melted with the gold in tation. The silver was recovered from the acid and used again. In the 19th century sulphuric acid replaced nitric acid and is cheaper to use. The chlorine ess (not to be confused with chlorination, the obsolete process of treating ores) was invented in 1869 in Australia where acid was expensive, and has become the usual method of refining. The gold is melted in clay pots and a stream of chlorine gas is bled through it (fig. S). The chlorine is absorbed by the silver which is present, and silver chloride is formed and rises to the surface of the molten metal whence it is skimmed off. The silver is recovered by electrolysis in another vessel. Most of the other metals are chloridized like silver ; but the gold is not attacked until nearly all the silver has been removed. When the gold is about 995 fine (containing 995 parts of gold per 1,00o), chlorine bubbles through to the surface freely, brown fumes appear, gold begins to be lost by volatilization and by spirting, and the work must be stopped. Platinum is not recovered by the process and, if present, remains in the gold, but the impurities which cause brittleness in minting are always removed. The cost of the process at Ottawa in 1916-18 when the Transvaal output was being refined was about 3 cents per oz. of gold.

In the United States mints the electrolytic process, introduced there in 1902, has since been used for refining most of the gold produced in North America. The gold is cast into thick plates which are suspended on gold or silver hooks in a porcelain cell filled with a solution of gold chloride containing some hydrochloric acid. The hooks are hung on metal rods and the whole series of plates and hooks are connected and are made the anode (fig. 6). A series of thin rolled plates of pure gold are suspended in the cell alternately with the impure plates and also connected to form the cathode. The liquid in the cell is heated to about 6o° C., and is continuously stirred, and a current of electricity is passed from the anode plates to the cathode through the liquid. The gold is dissolved from the anodes and is precipitated on the cathodes. At the end of the run it is stripped off the cathode plates and melted into bars. The silver is converted into insoluble chloride which falls to the bottom of the cell, and other metals, including platinum, dissolve in the liquid and remain in solution. The plati num is, however, subsequently recovered and sometimes pays for the whole operation. The process is somewhat slow, occupying three or four days, but the cathode gold is over ggg fine.

Alloys of Gold.

Gold alloys with silver in all proportions and the alloys are soft, malleable and ductile. The colour of gold gradually changes from yellow to white as the proportion of silver increases. When the silver is over 70% the alloys are white. "Green gold" (gold 75%, silver 25%) is used in jewellery and is of about the same composition as the electrum of the ancients. Gold-silver alloys are used to make trial plates, or standards of reference with which the fineness of gold wares and coins are compared. Copper hardens gold and forms alloys of reddish yellow colour at conveniently low melting points. These alloys are used for coinage. They blacken when heated, but the dis colouration is removed by sulphuric acid. The triple alloys of gold, silver and copper are malleable and ductile, with a rich gold colour. They are much used for the production of gold wares. Some zinc is of ten present in g carat gold. Hot nitric acid attacks all but the richer alloys of gold with silver or copper or both, and if the proportion of gold is no more than 33%, practically the whole of the silver and copper are removed in solution. Some of the gold-palladium and gold-platinum alloys are ductile and fit for use in jewellery. The alloys containing Io-2o% of palla dium are nearly white. Amalgams are alloys of gold and mercury. A piece of gold rubbed with mercury is immediately penetrated by it, turning white and becoming exceedingly brittle. The ductility is not always restored on driving off the mercury by heat. Solid amalgam contains 4o% or more of gold, but any excess of mercury over 6o% makes the amalgam pasty. The amalgam produced in gold mills (see AMALGAMATION ) is not a true amalgam but a collection of little nuggets of gold, coated and partly saturated with mercury. Lead when molten takes up gold readily, and zinc removes the gold from molten lead. The zinc and gold form a solid crust which floats on the surface of the lead. Advantage is taken of these properties in smelting. Gold forms alloys with many other metals but most of them are brittle, and none is of metallurgical importance. Even a minute quantity 0.02%) of tellurium, bismuth or lead makes gold brittle.See J. Percy, Metallurgy of Silver and Gold (188o) ; J. C. F. John son, Getting Gold (1897) ; W. R. Crane, A Treatise on Gold and Silver (1908) ; J. M. Maclaren, Gold; its Geological Occurrence and Geo graphical Distribution (1908) ; Sir T. K. Rose, The Metallurgy of Gold (1915) ; H. Garland and C. O. Bannister, Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy (1927) ; A. F. Taggert, Handbook of Ore Dressing (2927).

(T. K. R.)