Grafting in Animals

GRAFTING IN ANIMALS. Every gardener is well ac quainted with grafting in plants. But it is less well-known that pieces of animals too may be joined in permanent union. Grafting in animals is practised mainly for scientific purposes or for the restoration of weakened or lost parts. Therefore graft and stock are not always taken from different species (heteroplastic trans plantation) or races (alleloplastic), but may belong to samples of the same species and race (homoplastic) or even to one individual (autoplastic). It is as a rule easier to join pieces of the same species than pieces belonging to different species. In the warm blooded animals difficulties may arise even when two individuals of the same species are united by grafting, owing to blood incom patibility. With adult specimens of cold-blooded vertebrates this difficulty is less, and in their earlier stages and in invertebrate animals there seems to be little inconvenience from this source. In some types it is possible to join species belonging to different classes (dysplastic transplantation), e.g., amphibians and fish. The degree to which grafting may be carried on depends, too, on the injury a given animal can endure. Developed vertebrates will not stand the stoppage of their circulation and breathing in evitable with the removal of the head. But in embryos of frogs, before the circulation of blood has started, the head-region may be grafted on to the body even of another species, and such com pound monsters may even pass metamorphosis. As insects do not need their heads for breathing, and circulation continues without the head being present, grafting of the head is possible even in the imaginal instar, but it is not yet clear whether function is restored. There is no doubt that in lower organisms, such as worms, the head or other body-region can be grafted with functional success. Lengthened individuals may be obtained in embryos of amphib ians, tadpoles of abnormal length resulting. Two warm-blooded animals may be joined by bridges of tissue containing blood vessels and nerves. Side-to-side "Parabiosis" of this kind has been effected in rats, and reminds one of the "Siamese twins." Para biotic grafts have also been effected in frogs, newts, butterfly pupae, earthworms and hydrae. .

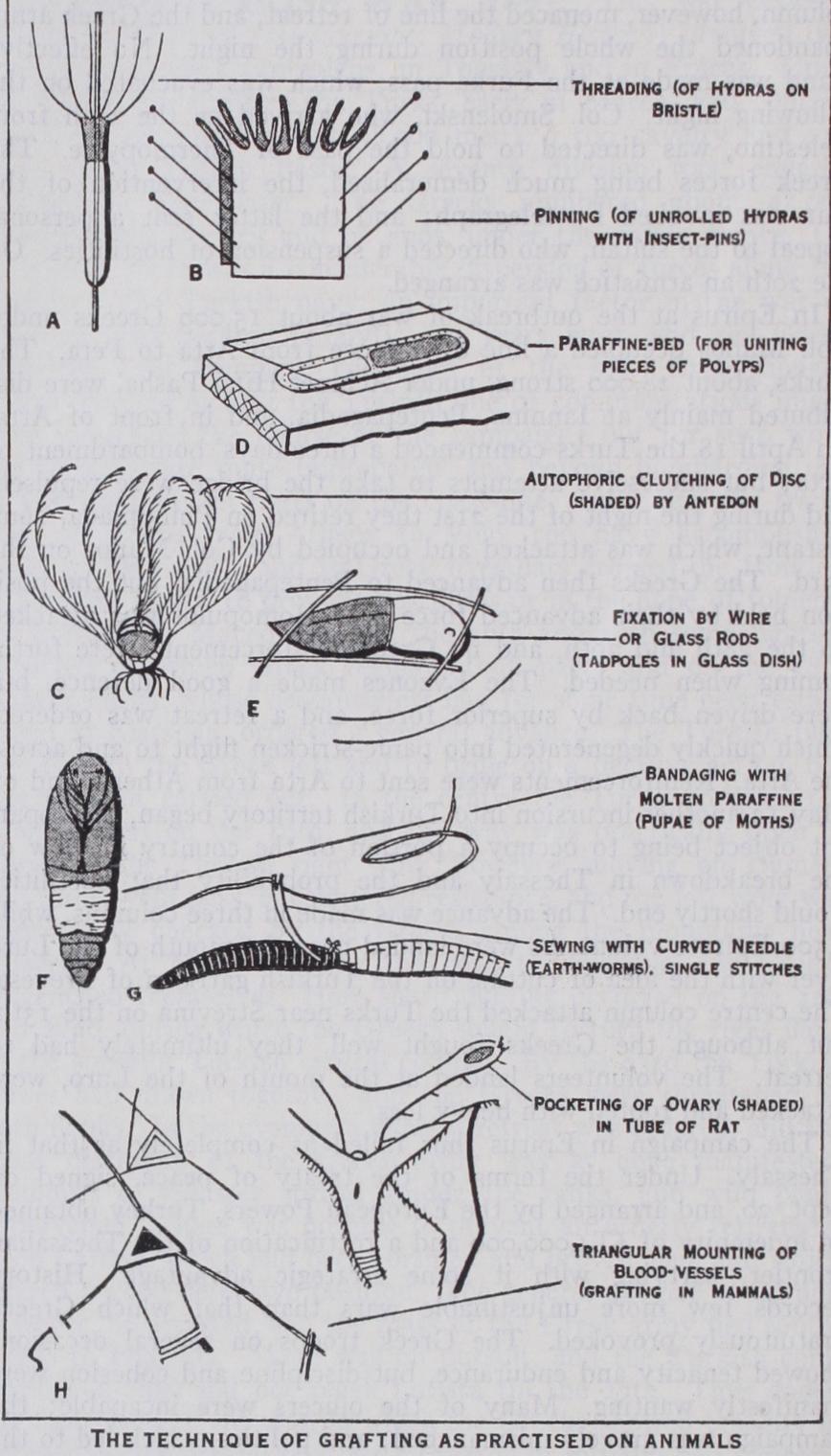

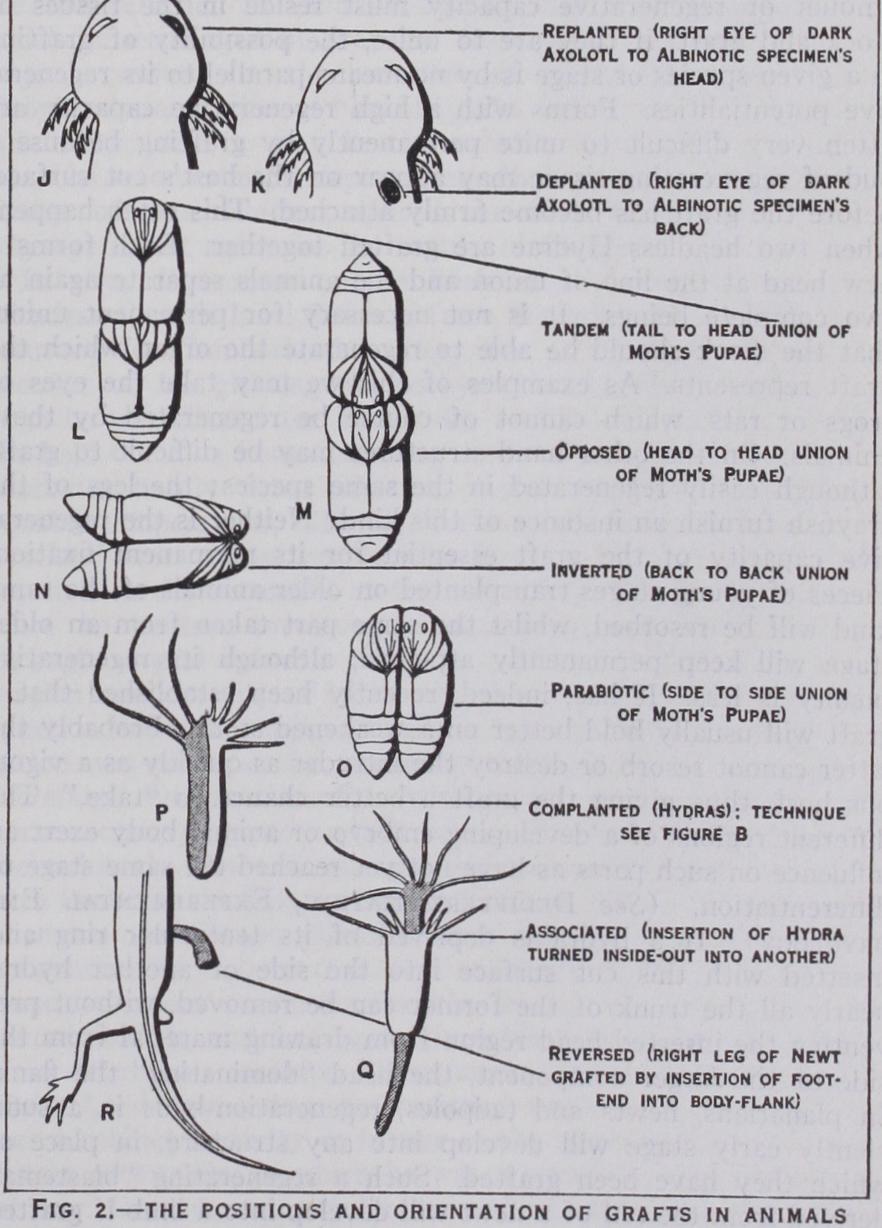

In certain cases the technique of grafting is even simpler in animals than in plants ; when the opportunity is given for the stock to grip the graft by its own means, not even tying or gluing is required (autophoric method). Thus the sea-lily Antedon, a relative of the starfish, bears a central disc easily detached. If another disc taken, let us say, from a specimen of different colour, be inserted into the groove left after the removal of the central disc, it will be clutched and kept in place by the tentacles sur rounding this spot. There is nothing mysterious about this re action as the tentacles also fold over the disc in the normal animal. In the case of the vertebrate eye an implanted eye-ball will keep in place by friction and the closing of the eyelids. To prevent these from opening prematurely, a fine pin or a silk stitch can be applied. Eyes can also be grafted in forms (e.g., fish and tad poles), which have no eyelids and have no means of pawing at the replanted eyes. Replantation of eyes has been successfully achieved in several species of fresh-water fish, newts, salamanders, frogs, toads, rats and in a rabbit. But only in very rare cases does sight return. Endeavours to apply grafting of eyes to restore vision to domestic animals have hitherto been unsuccessful. The lens alone may be grafted autophorically. The lens is extracted as in the operation for cataract. In fish, with cataract, the damaged lens, easily recognized by its opacity, is removed and a transparent lens from the eye of a healthy fish is slipped through the slit made by the operator's knife and is retained by the cornea. Transplantation of the lens in warm-blooded animals has not yet been recorded. Grafting of limbs, arm or leg, may be done in young tailed amphibians by inserting freshly detached limbs between the muscles of the shoulder pit or inguinal region, the contraction of the muscles holding them in place. In warm blooded animals, however, this method is not practicable and one has to resort to uniting every blood-vessel and nerve-trunk by stitching with catgut or silk. A special technique has been devised for this purpose. The suturing of nerves, however, in trans planting mammals' limbs has not proved satisfactory; no return of motility being secured. In cold-blooded animals sewing is widely used. Chrysalids of butterflies and moths have been united by girdles of paraffin after cutting on ice. Small sea or fresh water animals can be fixed in grooves of wax and covered by slips of glass or metal (silver, lead) so that the two cut ends touch each other; they then become united by the pressure. In this manner tadpoles, planarians and hydras may be dealt with. A convenient method of joining two or more pieces of hydra has been found by threading them on fine bristle. When the thread is taken out of the water, a drop of water remains on the grafts and draws them together by surface-tension.

Influence of Host.

Diverse scientific problems may be at tacked by animal grafting. One (which has also occupied the minds of many laymen), is the question as to the influence of a foster-mother on the characteristics of her nurslings. Ovaries of one female mammal may be grafted into another previously spayed female, and their eggs then fertilized by a chosen male. Then one can decide if the young show the characteristics one would predict from the crossing of this male with the female that has provided the ovary, or whether traits of the foster mother also appear. These experiments have furnished no sure evidence of the latter ever taking place. In some series apparent exceptions to this law have been observed, but it could be shown that in these cases either the races employed were not pure, or that regeneration of ovarian tissue had occurred in the foster-mother, the eggs fertilized by the male being derived from this source. This latter error is avoided by grafting ovaries inside the uterine horn and closing its end by a stitch. Thus eggs of the regenerating ovaries are prevented from passing into the tube. Much the same problem confronts us when parts of the body of an animal are grafted on to individuals of another race or species. Can the specific characters in the graft be changed by the influence of the host? Such an influence has been observed in a few special cases, but it is only colour that has spread from the stock into the graft, e.g., from a black axolotl to a pink eye grafted into its back from an albino of the same species. Here merely chemicals have diffused without altering the faculty of the graft to produce colour. But no sign has ever been observed of the host being able to change the tissues of the graft so as to assume a new specificity. The inability of the stock to change inherent differ ences applies also to merely individual characters. Newts or frogs of the same species differ in the rate of heart-beat. If the heart be extracted from one individual and grafted into the intestine of another, it retains its original rhythm of beating. When different stages of animals undergoing metamorphosis are used as stock and graft, an interesting point occurs: the eye of a caterpillar grafted on to the abdomen of the same species will develop at metamorphosis into the eye of the butterfly; the eye of a newt or salamander larva, grafted to the back of its neck, will meta morphosize into the eye of the adult form. This happens not only when stock and graft have been taken from individuals of equal size, stage and age, but also from those differing in these aspects to a wide degree. The explanation in amphibians is that metamor phosis is produced by the internal secretion of a gland, the thyroid; this secretion passes not only to the host but also to the graft. Metamorphosis sets in, not because the stage of the grafted eye has been suited to the stage of the host, but because the graft receives the same agency as the host at the same time. In insects some similar but as yet unknown agency is presumably at work.

Functioning of Grafts.

As the host may in this manner modify the graft, so, too, the graft can by internal secretion mod ify the host. In recent years numerous experiments have been per formed in grafting ovaries or testes into castrated vertebrates, females or males: the engrafted individuals displayed more or less distinctly the characters of the sex from which they had received the germinal glands by transplantation (see SEx). By joining embryos of amphibians the sex of one partner, usually the female, is changed. An analogous case is found, when the poste rior half of a male Hydra with functional testes is grafted on to the anterior half of a female. In all these cases the function of the graft is presumably established by diffusion of hormones. It is the same with grafts of other glands of internal secretion. If, on the contrary, such parts of the body as require nervous con nection for their normal function, are to be used in grafting, their function will only be completely restored, if the nerves of graft and stock unite. When the head of one earthworm, for instance, has been joined to the body of another, the movements of this compound will at first be irregular, the ingestion of food impossible. But later co-ordinate movements reappear, and food is taken in. Microscopical examination then reveals continuity of nerve-cord between the grafted head and the stock. In amphib ian larvae limbs grafted by the autophoric method may regain motility. Curiously enough, it seems as if the connection of one nerve-trunk of the host's limb with the graft is enough for restoring all kinds of motility to the transplanted limb, although several nerve-trunks normally run to different parts of the limb. As with motility, the return of sensation also depends on the regeneration of nerves. Special tests must be applied to prove return of eyesight after replantation of the eye described above. In fish and newts return of vision can be demonstrated by holding a wriggling worm behind the glass aquarium. If the animal can see, it will strike at the glass trying to catch the prey; a blind one will take no notice. In rats, jumping tests may be resorted to, as blind ones will not jump from a height. This evidence of return of vision has been corroborated by microscopical examina tion of the retina and optic nerve in the grafted eyes.

Antagonism of Graft and Re-growth.—Although a certain amount of regenerative capacity must reside in the tissues of stock and graft, if they are to unite, the possibility of grafting in a given species or stage is by no means parallel to its regenera tive potentialities. Forms with a high regenerative capacity are often very difficult to unite permanently by grafting because a bud of regenerating tissue may appear on the host's cut surface, before the graft has become firmly attached. This often happens when two headless Hydrae are grafted together. Each forms a new head at the line of union and the animals separate again as two complete beings. It is not necessary for permanent union, that the stock should be able to regenerate the organ which the graft represents. As examples of this we may take the eyes of frogs or rats, which cannot of course be regenerated by these animals. On the other hand structures may be difficult to graft, although easily regenerated in the same species : the legs of the crayfish furnish an instance of this kind. Neither is the regenera tive capacity of the graft essential for its permanent fixation. Pieces of young stages transplanted on older animals of the same kind will be resorbed, whilst the same part taken from an older stage will keep permanently attached, although its regenerative faculty is less. It has, indeed, recently been established that a graft will usually hold better on a weakened stock. Probably the latter cannot resorb or destroy the intruder as quickly as a vigor ous host, thus giving the graft a better chance to "take." The different regions of a developing embryo or animal body exert an influence on such parts as have not yet reached the same stage of differentiation. (See DEDIFFERENTIATION, EXPERIMENTAL EM