Graphic Methods in Mathematics

GRAPHIC METHODS IN MATHEMATICS. It is often found helpful to devise some scheme to show to the eye the relations between the different quantities involved in certain mathematical and statistical problems. In the simplest cases, the purpose of such "graphic methods" is merely to present the results of mathematical or statistical analysis. For instance, in the Statis tical Atlas of the United States, the census statisticians use various graphic devices to make readily available to others important results such as the average number of persons per square mile in various States or counties, The selection from a mass of statistical work of the results that are to be shown graphically, and the determination of the best statistical device for each case, are tasks which require both close familiarity with the details of the work and a broad view of the problems in which the results may be significant and of the mental attitude of those who will use the results. Graphic presen tation, if it is attempted at all, should be regarded as the culmina tion of a statistical study and not as an incidental diversion.

Graphic Methods As an Aid to Thinking.--In some cases graphic methods are much more than a vehicle for conveying information. Without their aid it is difficult to formulate the ideas which underlie many investigations of complicated quan titative relations, or to carry through the various steps of the investigation. The ordinary graph, obtained by plotting on co ordinate paper various values of one quantity against correspond ing values of another quantity, has become so familiar that we sometimes use it without realizing it. For instance, consider the following (hypothetical) description of the relation between average wages and term of service in a certain company: "On the average, wages rise, though at a decreasing rate, until about the tenth or twelfth year of service, and then flatten out, except for workmen appointed to supervisory positions. Salaries, on the other hand, continue to rise at a pretty uniform rate until the twentieth or twenty-fifth year of service, after which the averages are based on too few cases to establish a trend." While no graph is mentioned specifically, this statement would hardly be made except with the graph of earnings as a function of years of service definitely pictured in the mind of the writer, and would not be understood except with the same graph pic tured in the mind of the reader.

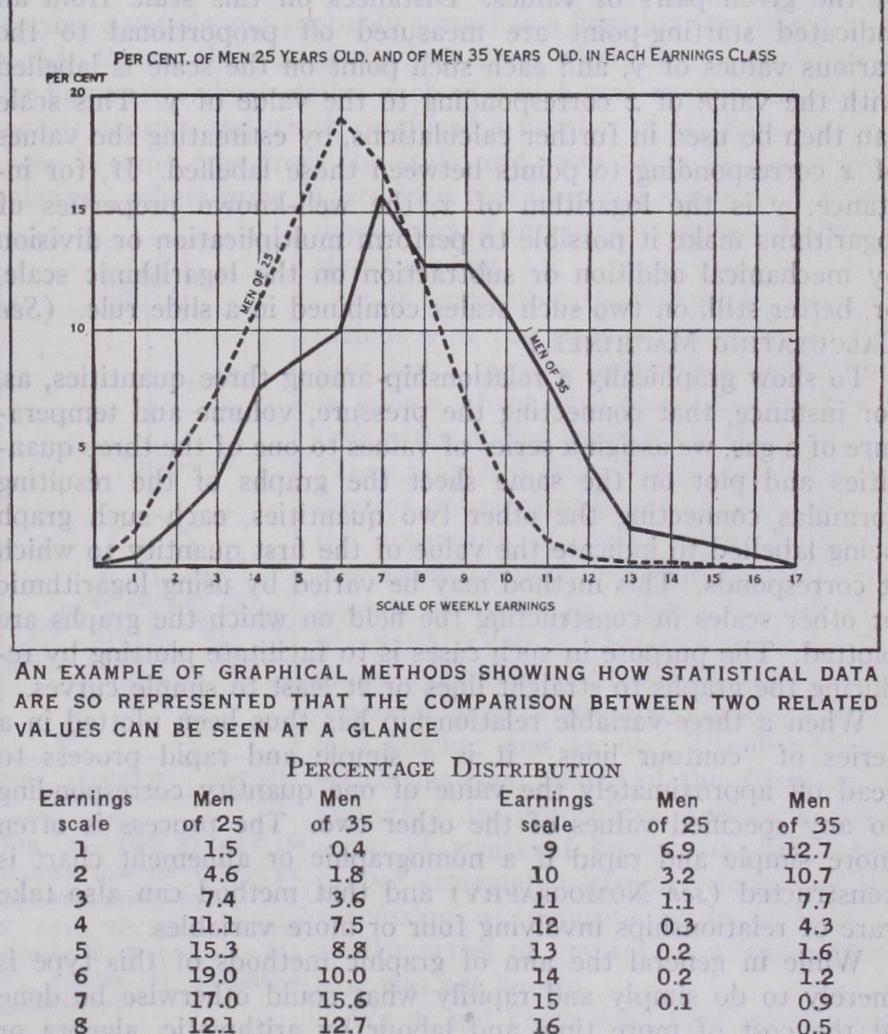

As a second illustration of the use of graphic devices as an aid to thought, consider the graphs of frequency distributions, as constructed by statisticians. The accompanying diagram, for in stance, compares the percentage distribution according to weekly earnings of male wage-earners 25 years old and of those 35 years old, in a certain factory. After inspection of these two frequency polygons, statements like the following may be made: (I) The earnings of different individuals of the same age differ considerably; therefore an average for any group is of little value as an indication of the number below any particular standard of pecuniary well-being.

(2) Relatively high earnings are more common among men of 35 than among men of 25; therefore a single distribution by earn ings of men of all ages is inadequate to measure the extent to which earnings are large enough for needs, which obviously vary with age.

(3) The earnings of men of 35 more frequently vary con siderably from the most typical amount than do those of men of 25. There is no point on the scale at which as large a percentage of 35 year old men are concentrated as of 25 year old men at "6" or "7" on the scale.

As these statements show, a diagram of this type provides a basis for beginning to think about the problems of variation which are the subject matter of statistical science. In such cases the graph is an instrument whereby a real idea can be definitely formulated, made clear to others, and used for guidance in the solution of problems.

Securing Approximate Numerical Results Rapidly.—On the basis of a limited number of paired values of the quantities x and y, obtained either by substitution in a formula or by observation of phenomena, a graph may be constructed by draw ing a smooth curve through the points representing these paired values. From the graph we may then read other pairs of values, thus avoiding additional observations or substitutions in the formula. In many cases this process of graphic interpolation is much shorter than the processes which it replaces, though usually not as accurate.

A variation of this scheme is to construct a scale on the basis of the given pairs of values. Distances on this scale from an indicated starting-point are measured off proportional to the various values of y, and each such point on the scale is labelled with the value of x corresponding to the value of y. This scale can then be used in further calculations, by estimating the values of x corresponding to points between those labelled. If, for in stance, y is the logarithm of x, the well-known properties of logarithms make it possible to perform multiplication or division by mechanical addition or subtraction on the logarithmic scale, or, better still, on two such scales combined in a slide rule. (See