Grass and Grassland

GRASS AND GRASSLAND. Since the grasses (q.v.) constitute one of the most widespread of flowering plants on most farms, the land not actually cultivated will either be in grass or will revert naturally to grass in time if left alone. This pasture land has always been an important part of the economy of the farm ; but with the advent of "cheap corn" its importance has been increased, and much more attention has been given to the study of the different species of grass, together with their char acteristics and the improvement of a pasture generally, as well as to the "laying down" of arable land to grass where tillage farming has not paid. Since the World War many of the scientific insti tutions connected with agricultural research (q.v.) have therefore been engaged in experimenting with, and developing, individual pasture plants or pastures as a whole. The improvement of pas ture lands has been followed by a corresponding increase of live stock of all kinds, coupled with a reduction in the working ex penses as compared with arable farming.

Even on wholly arable farms there are usually certain courses in the rotation of crops devoted to grass (or a corresponding leguminous crop, such as clover). Thus the Norfolk four-course rotation is corn, roots, corn, clover; the Berwick five-course is corn, roots, corn, grass, grass ; the Ulster eight-course, corn, flax, roots, corn, flax, grass, grass, grass; and so on, to the point where the grass remains down for five years, or is left indefinitely.

Permanent grass may be grazed by live stock and classed as pasture pure and simple, or it may be cut for hay. In the latter case it is usually classed as "meadow" land, and often forms an alluvial tract alongside a stream, but as grass is often grazed and hayed in alternate years, the distinction is not a hard and fast one. Two classes of pasturage, however, temporary and permanent, may be distinguished. But the latter again consists of two kinds, the permanent grass natural to land that has never been culti vated, and the pasture that has been laid down artificially on land previously arable and allowed to remain and improve itself in the course of time. Thus, the existence of ridge and furrow on many old pastures in Great Britain shows that they were cultivated at one time.

Often a newly laid down pasture will decline markedly in thickness and quality about the fifth and sixth year, and then begin to thicken and improve year by year afterwards. This is usually attributed to the fact that the unsuitable varieties die out, and the "naturally" suitable varieties only come in gradually. This trouble can be largely prevented, however, by a judicious selection of seed, and by subsequently manuring with phosphatic manures, with farmyard or other bulky "topdressings," or by feeding sheep with cake and corn over the field.

Grasses and Clovers.

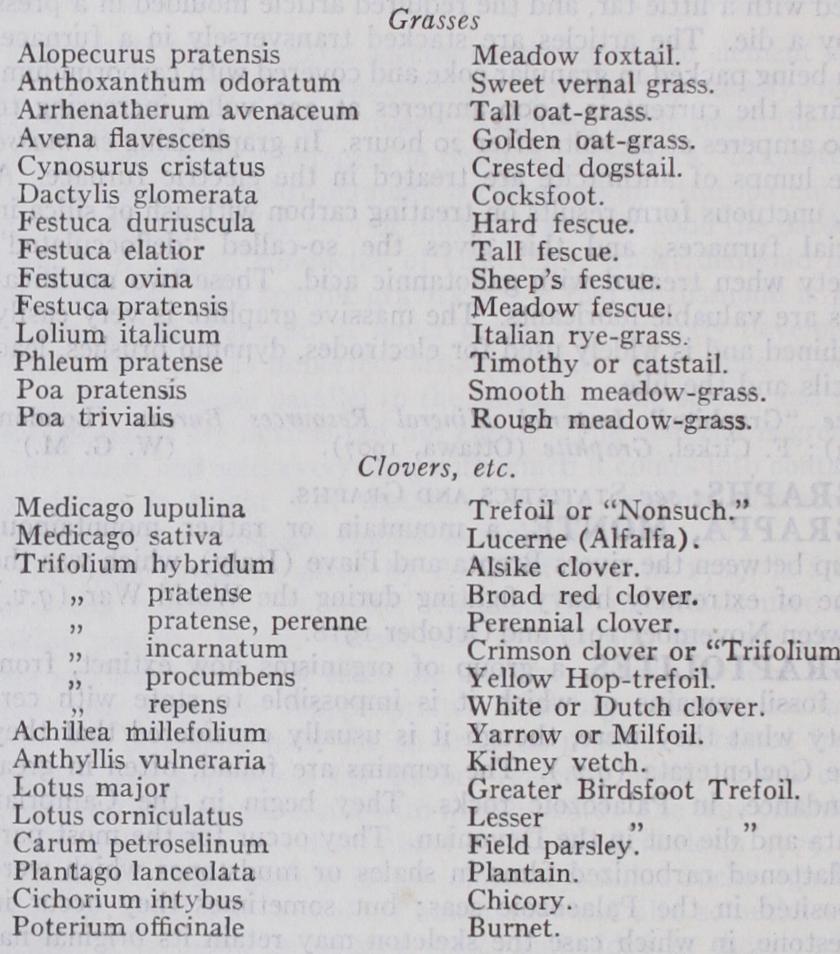

All the grasses proper belong to the natural order Gramineae, to which order also belong all the "corn" plants cultivated throughout the world, also many others, such as bamboo, sugar-cane, millet, rice, etc., etc., which yield food for mankind. Of the grasses which constitute pastures and hay fields, over Too species are classified by botanists, with many varieties in addition, but the majority of these, though often forming a part of natural pastures, are worthless or inferior for farming purposes. The grasses of good quality which should form a "sole" in an old pasture and provide the bulk of the forage on a newly laid down piece of grass are only about a dozen in num ber (see below), and of these there are only some six species of the very first importance and indispensable in a "prescription" of grass seeds intended for laying away land in temporary or permanent pasture. Dr. W. Fream caused a botanical examination to be made of several of the most celebrated pastures of Eng land, and, contrary to expectation, found that their chief con stituents were ordinary perennial rye-grass and white clover. Many other grasses and legumes were present, but these two formed an overwhelming proportion of the plants.In ordinary usage the term grass, pasturage, hay, etc., includes many varieties of clover and other members of the natural order Leguminosae (q.v.) as well as other "herbs of the field," which, though not strictly "grasses," are always found in a grass field, and are included in mixtures of seeds for pasture and meadows. The following is a list of the most desirable or valu able agricultural grasses and clovers, which are either actually sown or, in the case of old pastures, encouraged to grow by drain ing, liming, manuring and so on:— The predominance of any particular species is largely de termined by climatic circumstances, the nature of the soil and the 'treatment it receives. In Great Britain, in limestone regions sheep's fescue has been found to predominate ; on wet clay soil the dog's bent (Agrostis canine) is common; continuous manur ing with nitrogenous manures kills out the leguminous plants and stimulates such grasses as cocksfoot; manuring with phosphates stimulates the clovers and other legumes ; and so on.

The Best Grasses.—As to the best kinds of grasses to sow in making a pasture out of arable Iand, experiments at Cambridge, England, have demonstrated that of the many varieties offered by seedsmen only a very few are of any permanent value. A complex mixture of tested seeds was sown, and after five years an examination of the pasture showed that only a few varieties survived and made the "sole" for either grazing or forage. These varieties in the order of their importance were:— Timothy . 6 White clover 4 Meadow f oxtail . . . . . . . . . 2 The figures represent approximate percentages Before laying down grass it is well to examine the species already growing round the hedges and adjacent fields. An inspec tion of this sort will show that the Cambridge experiments are very conclusive, and that the above species are the only ones to be depended on. Occasionally some other variety will be prominent, but if so there will be a special local reason for this. On the other hand, many farmers when sowing down to grass like to have a good bulk of forage for the first year or two, and therefore include several of the clovers, lucerne, Italian rye-grass, evergreen rye-grass, etc., knowing that these will die out in the course of years and leave the ground to the more permanent species.

There are also several mixtures of "seeds" (the name given in agriculture to grass seed mixtures) which have been adopted with success in laying down permanent pastures in some localities.

Arthur Young more than i oo years ago made out a mixture to suit chalky hillsides; Faunce de Laune (Sussex) in more recent times was the first to study grasses and advocated leaving out rye-grass of all kinds ; Lord Leicester adopted a cheap mixture suitable for poor land with success; Mr. Elliot (Kelso) introduced many deep-rooted "herbs" in his mixture with good results. Typical examples of such mixtures are given above.

Temporary Pastures.

These are commonly resorted to for rotation purposes, and in these the bulky fast-growing and short lived grasses and clovers are given the preference. Three examples of temporary mixtures are given below :— Where only a one-year hay is required, broad red clover is often grown, either alone or mixed with a little Italian rye-grass, while other forage crops, like trefoil and trefolium, are often grown alone.In recent investigations wild White clover—botanically similar to ordinary White Dutch clover (which is usually included in grass seed mixtures)—has come very much to the front, and now a small amount (from half to a whole pound) of seed per acre is often included in those mixtures intended to remain down for several years. It improves the feeding "quality" of pastures very much, does not die out in a year or two, and enriches the soil with nitrogenous compounds, so that if and when the grass land is ploughed up for corn growing again after a few years, the fertility is greatly improved. Several other varieties of clover are also being experimented with besides those mentioned in the above prescriptions, such as Montgomeryshire late flowering red clover, Cornish "marl-grass," subterranean clover and so on, while many grasses are also being further developed.

Fertilizers.

Apart from the selection and improvement of the individual plants which compose a pasture or hay field there is the general treatment by manuring. The grazing of land for generations by live stock, and the continuous selling off of beef, mutton, wool, milk, etc., reduces the fertility of the soil, and so in most cases a return in the shape of manure is desirable. The older and more usual way of renovating the fertility of grasslands was to feed the cattle or sheep thereon with an allowance of feed ing cakes or corn of some sort. This enriched their manure and so helped to keep up the fertility of the land; but it has now been repeatedly demonstrated that judicious chemical manuring of either an old or a new grass field can increase the crop yield immensely. (See. FERTILIZERS and FEEDING STUFFS.) The most suitable chemicals are those of a phosphatic nature such as basic slag, North African phosphate, bone superphosphate, etc. The effect of these has been most satisfactory in the great majority of cases, when applied at the rate of from four to ten cwt. per acre, and repeated at intervals of, say, five years. On the lighter class of soils an addition of a potassic manure has often helped to get good results. In the Rothamsted experiments continuous manuring with "mineral manures" (no nitrogen) on an old meadow has reduced the grasses from 71 to 64% of the whole, while at the same time it has increased the Leguminosae from 7% to 24%. On the other hand, continuous use of nitrogen ous manure in addition to "minerals" has raised the grasses to 94% of the total and reduced the legumes to less than I %.Besides manuring so as to increase the yield of food, and thus enable more live stock to be carried, there have been introduced better methods of grazing. It has been found that if a pasture is allowed to run to seed there is a loss in food economy, the stalks and seeds being of inferior value ; to prevent the development of these the land should be heavily stocked so as to keep the grass grazed well down, and thus fresh leafy growth is encouraged instead of seed stalks. An old pasture is liable to show rough growth in spots which the animals do not readily eat over; such parts are improved by cutting over with a mowing machine, while extra phosphatic top-dressing should be applied thereto.

Rotation Grazing.

A rotation of grazing is also an im proved method, whereby the stock is moved from field to field, so that each field is hard grazed in turn and then shut up till a fresh lot of leaves spring up. Some investigators in this line have divided up their fields into small paddocks to be grazed in rotation, while an intensive form of this principle has long been practised in the Channel islands, Denmark, and to a less extent in some other European countries. This consists in tethering the animals to be grazed singly to pegs or corkscrew pins fixed in the ground, with an allowance to each of several yards of rope or chain attached to a neck-band. Each animal eats off a circular patch of grass very closely, and is then moved on to a fresh spot. It involves a large amount of personal attention on the part of attendants as compared with ordinary grazing, but on the other hand the growth of the grass is controlled and made the most of.In Great Britain a heavy clay soil is usually preferred for pasture, both because it takes most kindly to grass and because the expense of cultivating it makes it unprofitable as arable land when the price of corn is low. On light soil the plant frequently suffers from drought in summer, the want of moisture preventing it from obtaining proper root-hold. On such soil the use of a heavy roller is advantageous, and indeed on any soil except heavy clay frequent rolling is beneficial to the grass, as it promotes the capillary action of the soil-particles and the consequent ascension of ground water. In addition the grass on the surface helps to keep the moisture from being wasted by the sun's heat. Frequent harrowing on heavy clay soil is also beneficial.

The graminaceous crops of western Europe generally are similar to those enumerated. Elsewhere in Europe are found certain grasses, such as Hungarian brome, which are suitable for intro duction into the British Isles. The grasses of the American prairies also include many plants not met with in Great Britain. Some half-dozen species are common to both countries: Kentucky "blue-grass" is the British Poa pratensis; couch grass (Triticum repens) grows plentifully without its underground runners; bent (Agrostis vulgaris) forms the famous "red-top," and so on. But the American buffalo-grass, the Canadian buffalo-grass, the "bunch" grasses, "squirrel-tail" and many others which have no equivalents in the British Isles, form a large part of the prairie pasturage. There is not a single species of true clover found on the prairies, though cultivated varieties can be introduced.

The separate articles on HAY; LUCERNE (Alfalfa) ; CLOVER and the like, may be consulted as well as the articles on ROTATION OF CROPS ; CULTIVATION ; WEED DESTRUCTION, etc. For grass cultivation of lawns and playing greens, see GREENS.

(P. MCC.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J. F. Armstrong, British Grasses and their EmployBibliography.-J. F. Armstrong, British Grasses and their Employ- ment in Agriculture (Cambridge, 1917) ; R. G. Stapledon and J. A. Hanley, Grass Land: Its Management and Improvement (Oxford, 1927), contains a full, selected bibliography ; W. J. Malden, Grassland Farming (1924) . All three works are illustrated.

In the United States, the region from 95° W. to the foothills of the Rocky mountains was originally occupied by native grasses. This almost treeless area which extends northward to Saskatche wan and Alberta is still occupied by native grasses, except where it has been placed under cultivation. The eastern part of this belt, including Iowa and Illinois, has an annual rainfall of 20 to 3o in. and is largely cultivated; tall native grasses are replaced by others, mostly European. The most extensive of the smaller areas of natural grassland are between the Rocky mountains and Pacific coast ranges. In arctic northern Canada and Alaska the grazing lands or tundra, mostly of mosses and lichens, with a few hardy summer grasses and woody plants, are useful only for rein deer and wild animals.

In South America are several well defined, extensive grass areas. In the central plateau are two large natural grasslands, the Orinoco llanos (Venezuela) and the Argentine pampas. In the higher sections of eastern and southern Brazil is considerable grassland between forests. Many introduced species have some what replaced the native grasses.

Mexico and Central America have no well defined extensive grasslands.

Meadows and Hay Plants.—In humid regions the meadows or hay fields are largely seeded to tame grasses or mixtures of grasses and legumes. Mixtures ordinarily yield better and more palatable hay than pure cultures and they are preferred because: production is more uniform and permanent with both short and long lived plants; loss through insects, disease and climate is less ; inclusion of some low-growing, turf-forming grasses with the taller species results in much better pasture if the aftermath is grazed or if the meadow is converted into a pasture ; legumes stimulate growth and probably increase the protein content of the grasses.

The number of seed mixtures for meadows is legion. Gener ally, however, complex mixtures are not popular in America and consequently there is less justification for complexity in mixtures for meadows than for pastures. Where hay is the crop and plants of varying habits are represented in the mixture they must mature at approximately the same time. Reliable mixtures (I) the stand ard for north-east United States and south-east Canada, timothy and red clover, sometimes with alsike clover and redtop added. For low, wet lands, redtop and alsike alone; (2) in the southern part of the above region where timothy does not succeed, par ticularly on dry uplands, orchard grass, tall oat grass and alsike are best; (3) in the semiarid or subhumid regions farther west, brome grass (Bromus inermis) and slender wheat grass (Agropy ron tenerum) are most reliable, and where alfalfa thrives it should be included.

Hay Plants.

Timothy is a good hay plant, but nearly all timothy and clover hay are from rotations. The most common of these is corn, oats, wheat, followed by two years of timothy and clover, these being sown in the wheat. The usual rate of seeding is timothy, 12 lb.; red clover, 8 pounds. When alsike and redtop are added the quantities are 2 and 4 lb., respectively.In the Gulf States the principal hay is Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense). On rich, black soils it usually grows spontaneously, excluding other plants. Because of the difficulty of eradicating it, it is rarely seeded intentionally. Mixtures of Johnson grass and clover or other legumes are impractical except when the meadow is plowed up to stimulate a renewed growth.

In the central West and on irrigated lands in the more arid western States, alfalfa is the chief and often the only hay crop. It is also the main one in Argentine. Where alfalfa succeeds well there is no other hay plant so productive and generally desirable. It is very palatable and nutritious and several cuttings may be made yearly. Seeding should be on well prepared soil at 15 to 25 lb. per acre.

On the Pacific coast and in some interior localities cereal crops (wheat, oats, barley and rye) are often cut for hay. Certain annual grasses and legumes are also important. Among these are millets, sorghum, Sudan grass, cowpeas, soybeans, vetches and field peas. Of the hay harvested in the United States in 1919, 26% was timothy; 19% alfalfa; 17% clovers; 16% native or wild plants; 5% sorghums and Sudan grass; all other hay plants produced 17%. Since 1919 timothy has declined and alfalfa has increased in importance.

Fertilizers.—The use of fertilizers on meadows in the humid region is undoubtedly warranted, although where hay is part of a general rotation the grain crops are usually fertilized. In this way the grass benefits only from the residual effect. The average yield of meadows in north-east United States and south-east Canada is about 1.3 tons per acre. With fertilizers, yields of 2.5 to 4 tons per acre have been maintained for years. Nitrogen fertilizers alone encourage grasses at the expense of legumes and should rarely be used indefinitely on a mixed meadow without phosphate and potash. Brooks recommends for hay meadows : nitrate of soda, 15o to 25o lb.; basic slag meal, 30o to 400 lb.; high grade sulphate of potash, 75 to ioo pounds. On peat and certain sandy soils potash is particularly effective. On clay or loam of moderate fer tility where clover is in the mixture, phosphate of some kind is almost essential. For alfalfa, soil acidity is corrected by lime.

Pastures and Pasture Plants.

Pastures are land areas cov ered with grass and other plants for grazing. Until the last decade American agricultural agencies devoted little study to them. In the United States about 55% of all land is used for grazing. Of this I,oS5,000,000 ac., only a little less than one-tenth is arable land in rotation or permanent pastures like those of the British Isles and western Europe. The remainder is arid grassland and desert shrub-land too dry for cultivation, or forest and cut-over or burned-over land not suited for pastures until improved. Probably 5o% of the sustenance of American live stock is obtained from pastures. Generally American pasture feed costs approxi mately one-eighth as much as that from harvested crops. Pastures are valuable also on hillside lands in preventing soil erosion. True grasslands comprise improved and natural pastures (called ranges when extensive). The acreage of natural pastures is about ten times that of the tame, but their unit carrying capacity is only one-fifth as great. They are mostly in the western half of the United States, excluding, however, the Pacific slope. In the semiarid or Great Plains region are the "short grasses," the most important of which are buffalo (Buchloe dactyloides), and grama grasses (Bouteloua sp.) in the north and the grama grasses and mesquite (Hilaria sp.) in the south. Mixed with these are taller needle grasses (Aristida sp.), and some bluestem (Andropogon sp.) , and wheat-grass (Agropyron sp.) . Farther west in the more arid sections are bunch grasses, mostly wheat-grass, fescue and brome with some salt grasses in alkaline areas. Humid south eastern States still have native grasses, although practically all grassland in the eastern or humid section is made up of introduced grasses. These natural pastures in the south-eastern States are mostly cut-over or burned-over forest lands now carpeted with the broom sedges (Andropogon sp.) and panic and wire grasses.In 1925 about one-third of the arable land was in permanent pasture. Probably a to 3 of a farm of average size favourable to live stock could be profitably devoted to permanent pasture. Grasses.—The following discussion of pasture plants and seed mixtures applies to the humid regions. Natural pastures in arid and semi-arid regions remain practically unimproved. Probably 75% of pasture herbage is grasses. (In common usage any fine stemmed hay or pasturage plant such as clover, alfalfa, lespedeza and vetch, is called grass. This, however, cannot be justified.) In America north of Mexico there are some 1,5oo species of true grasses. Many of these are in natural pastures, but only a few are important, and in the improved pastures less than a dozen grasses are generally found. These are in the order of their importance : Kentucky bluegrass, Bermuda grass, timothy, red top, Rhode Island bent, carpet grass, Canada bluegrass, orchard grass, Johnson grass and crab grass. On well drained, fertile Northern soils, Kentucky bluegrass and white clover are pre dominant. On wet soils in the interior, redtop and alsike clover are preferred to bluegrass and white clover. Redtop and the other species of Agrostis, such as Rhode Island bent and creeping bent are also prominent on less fertile New England coastal soils. Orchard grass thrives on drier and shaded soils, and in parts of Virginia is valued above Kentucky bluegrass and redtop. South of Virginia, Bermuda grass is the premier pasture grass on up lands and on silt and clay coastal soils, while carpet grass is the best for moist sandy soils. Both usually grow with lespedeza, or Japan clover. Canada bluegrass grows mostly in southern Canada and northern United States on poorer soils. Kentucky bluegrass is valued most on limestone soils which are also rich in phosphates, as in Kentucky.

Legumes.—Include clovers, alfalfa, melilot, lespedeza, yellow trefoil, etc. The most important of these for pasture are white, red and alsike clover and lespedeza. These are almost always mixed with one or more grasses for grazing. The first three are largely confined to the northern half of the region, although white clover thrives on better soil types even near the Gulf of Mexico. Lespedeza (Lespedeza striata) is an annual which, however, reseeds itself and thus serves as a perennial. Although introduced, it is abundant in uncultivated fields of all the southern States west to Texas and adds immeasurably to the summer pastures. Bur clover and yellow trefoil, both species of Medicago, are useful southern winter legumes. Alfalfa in pure stands is often pastured, especially with hogs ; but it is not good for cattle and horses as it often causes bloat (hoven). Melilot or sweet clover is gaining favour as temporary pasture.

Piper roughly estimates the relative value of the various pas ture grasses and legumes as follows :—Kentucky bluegrass, 35; white clover, I o; Bermuda grass, 8; timothy, 7; redtop, 7; red clover, 4; alfalfa, 4; Rhode Island bent, 4; carpet grass, 3; Alsike clover, 3; Canada bluegrass, 3; orchard grass, 2; Johnson grass, 2; Lespedeza, 2; crab grass, 2; all others, 2. While most of these are European there are several grasses considered of first importance in English pastures, such as Italian and perennial rye grasses which are seldom found in America.

Pasture Mixtures.—Quick growing but less permanent grasses are often added to furnish pasturage while slower growing grasses are forming a turf. The complex mixtures often recommended in England are not profitable in America. Some mixtures that have been found satisfactory under various climatic and soil conditions In the Kentucky bluegrass region pasture will finally consist almost entirely of bluegrass, redtop, and white clover, with a sprinkling of orchard grass. The timothy, Italian and perennial rye-grasses are added solely to provide abundant pasturage the first year. The same gradual transformation will take place where Canada bluegrass is seeded, and on the sandy soils the fescues are likely to predominate. In the South, Bermuda grass often excludes all other grasses and legumes on the heavy soils as does carpet grass on moist, sandy soils. Lespedeza persists here more than either white clover or yellow trefoil. Pastures of these grasses and lespedeza only are unproductive in winter and spring. Therefore winter growing legumes like white clover and yellow trefoil must be encouraged. Bur clover should be added, or grown in a supplementary pasture.

Temporary pastures are more often of annual grasses and legumes than of perennials. Sometimes the aftermath of a meadow (hayfield) is grazed for one or two months and the winter grains, wheat, rye and oats, are pastured a short time in late fall and winter. Vetch and oat mixtures make excellent early spring pas ture, and peanuts, cowpeas and soy beans are useful in summer wherever they will grow. Among annual and biennial plants which make good temporary pasture are melilot (sweet clover), Sudan grass, and bur clover. Sweet clover and Sudan grass are much grown in the Central West and are very productive. Bur clover in the Gulf States is extremely useful because it is productive and nutritious in late winter and early spring.