Gravitation

GRAVITATION, in physical science is that mutual action between masses of matter by virtue of which every such mass tends toward every other with a force varying directly as the product of the masses and inversely as the square of their distances apart. Although the law was first clearly and rigorously formulated by Sir Isaac Newton, the fact of the action indicated by it was more or less clearly seen by others. Even Ptolemy had a vague con ception of a force tending toward the centre of the earth which not only kept bodies upon its surface, but in some way upheld the order of the universe. John Kepler inferred that the planets move in their orbits under some influence or force exerted by the sun; but the laws of motion were not then sufficiently developed, nor were Kepler's ideas of force sufficiently clear, to admit of a precise statement of the nature of the force. C. Huygens and R. Hooke, contemporaries of Newton, saw that Kepler's third law implied a force tending toward the sun which, acting on the several planets, varied inversely as the square of the distance. But two requirements necessary to generalize the theory were still wanting. One was to show that the law of the inverse square not only represented Kepler's third law, but his first two laws also. The other was to show that the gravitation of the earth, following one and the same law with that of the sun, extended to the moon. Newton's researches showed that the attraction of the earth on the moon was the same as that for bodies at the earth's surface, only reduced in the inverse square of the moon's distance from the earth's centre. He also showed that the total gravitation of the earth, assumed as spherical, on external bodies, would be the same as if the earth's mass were concentrated at its centre. This led at once to the statement of the law in its most general form.

The law of gravitation states that two masses and M2, distant d from each other, are pulled together each with a force where G is a constant for all kinds of matter—the gravitation constant. The acceleration of M2 towards or the force exerted on it by per unit of its mass is therefore The aim of the experiments to be described here may be re garded either as the determination of the mass of the earth in grammes, most conveniently expressed by its mass _ its volume, that is, by its mean density A , or the determination of the gravi tation constant G. Corresponding to these two aspects of the problem there are two modes of attack. Suppose that a body of mass m is suspended at the earth's surface where it is pulled with a force w vertically downwards by the earth—its weight. At the same time let it be pulled with a force p by a measurable mass M which may be a mountain, or some measurable part of the earth's surface layers, or an artificially prepared mass brought near m, and let the pull of M be the same as if it were concentrated at a distance d. The earth pull may be regarded as the same as if the earth were all concentrated at its centre, distant R.

If then we can arrange to observe w/p we obtain A, the mean density of the earth.

But the same observations give us G also. For, putting m=w/ g in (2), we get In the second method of attack the pull p between two arti ficially prepared measured masses M1, M2, is determined when they are a distance d apart, and since p = we get at once G = But we can also deduce A. For putting w=mg in (r) we get Experiments of the first class in which the pull of a known mass is compared with the pull of the earth may be termed experiments on the mean density of the earth, while experiments of the second class in which the pull between two known masses is directly measured may be termed experiments on the gravitation constant.

We shall, however, adopt a slightly different classification for the purpose of describing methods of experiment, viz.:— (1) Comparison of the earth pull on a body with the pull of a natural mass as in the Schiehallien experiment.

(2) Determination of the attraction between two artificial masses as in Cavendish's experiment.

(3) Comparison of the earth pull on a body with the pull of an artificial mass as in experiments with the common balance.

It is interesting to note that the possibility of gravitation experi ments of this kind was first considered by Newton, in both of the forms (I) and (2) . In the System of the World (3rd ed., 1737, P. 40) he calculates that the deviation by a hemispherical moun tain, of the earth's density and with radius 3 m., on a plumb line at its side will be less than 2 minutes. He also calculates (though with an error in his arithmetic) the acceleration towards each other of two spheres each a foot in diameter and of the earth's density, and comes to the conclusion that in either case the effect is too small for measurement. In the Principia, bk. iii., prop. x., he makes a celebrated estimate that the earth's mean density is five or six times that of water. Adopting this estimate, the deviation by an actual mountain or the attraction of two terres trial spheres would be of the orders calculated, and regarded by Newton as immeasurably small.

Whatever method is adopted the force to be measured is very minute. This may be realized if we here anticipate the results of the experiments, which show that in round numbers A = 5.5 and G —16,000,00o when the masses are in grammes and the distances in centimeters.

i. Comparison of the Earth Pull with That of a Natural Mass.—Bouguer's Experiments.—The earliest experiments were made by Pierre Bouguer about 1740, and they are recorded in his Figure de la terre (1749) . They were of two kinds. In the first he determined the length of the seconds pendulum, and thence g at different levels. Thus at Quito, which may be regarded as on a table-land 1,466 toises (a toise is about 6.4 ft.) above sea-level, the seconds pendulum was less by than on the Isle of Inca at sea-level. But if there were no matter above the sea-level, the inverse square law would make the pendulum less by at the higher level. The value of g then at the higher level was greater than could be accounted for by the attraction of an earth end ing at sea-level by the difference 1,1.8 — 1,331 = 6.983 , and this was put down to the attraction of the plateau 1,466 toises high or the attraction of the whole earth was 6,983 times the attraction of the plateau. Using the rule, now known as "Young's rule," for the attraction of the plateau, Bouguer found that the density of the earth was 4.7 times that of the plateau, a result certainly much too large.

In the second kind of experiment he attempted to measure the horizontal pull of Chimborazo, a mountain about 20,000 ft. high, by the deflection of a plumb-line at a station on its south side. Suppose that two stations are fixed one on the side of the moun tain due south of the summit, and the other on the same latitude but some distance westward, away from the influence of the moun tain. If at the second station a star is observed to pass the meridian, for simplicity we will say directly overhead, then a plumb-line will hang down exactly parallel to the observing tele scope. If the mountain were away it would also hang parallel to the telescope at the first station when directed to the same star. But the mountain pulls the plumb-line towards it and the star appears to the north of the zenith and evidently mountain pull/earth pull= tangent of the angle of displacement of zenith.

Bouguer observed the meridian altitude of several stars at the two stations, and after making the necessary corrections he con cluded that the earth was nearly 13 times as dense as the moun tain, a result several times too large. But the work was carried on under enormous difficulties owing to the severity of the weather, and no exactness could be expected. The importance of the experiment lay in its proof that the method was possible.

Maskelyne's Experiment.—In 1774 Nevil Maskelyne (Phil. Trans., P. 495) made an experiment on the deflection of the plumb-line by Schiehallien, a mountain in Perthshire, which has a short ridge nearly east and west, and sides sloping steeply on the north and south. He selected two stations on the same meridian, one on the north, the other on the south slope, and by means of a zenith sector, a telescope provided with a plumb-bob, he determined at each station the meridian zenith distances of a number of stars. From a survey of the district made in the years 1774-1776 the geographical differences of latitude between the two stations was found to be 42.94 seconds, and this would have been the difference in the meridian zenith distances of the same star at the two stations in the absence of the mountain. But at the north station the plumb-bob was pulled south and the zenith was de flected northwards, while at the south station the effect was re versed. Hence the angle between the zeniths, or the angle between the zenith distances of the same star at the two stations was 54.2 seconds, or the double deflection of the plumb-line was say 1 1.2 6 seconds. The computation of the attraction of the mountain on the supposition that its density was that of the earth was made by Charles Hutton from the results of the survey (Phil. Trans., 1778, p. 689). He found that the deflection should have been greater in the ratio 17,804 : 9,933 say 9 : 5, whence the density of the earth comes out at g that of the mountain. Hutton took the density of the mountain at 2.5, giving the mean density of the earth 4.5, a figure revised later by Playfair (Phil. Trans., 1811, p. 347) Airy's Experiment.—In 18S4 Sir G. B. Airy (Phil. Trans., 1856, p. 297) carried out at Harton pit near South Shields an experi ment which consisted in comparing gravity at the top and at the bottom of a mine by the swings of the same pendulum, and thence finding the ratio of the pull of the intervening strata to the pull of the whole earth. The principle of the method may be under stood by assuming that the earth consists of concentric spherical homogeneous shells, the last of thickness h equal to the depth of the mine. Let the radius of the earth to the bottom of the mine be R, and the mean density up to that point be A . This will not differ appreciably from the mean density of the whole. Let the density of the strata of depth h be 8. Denoting the values of gravity above and below by and gb we have Stations were chosen in the same vertical, one near the pit head, another 1,25o ft. below in a disused working, and a com parison clock was fixed at each station. Two invariable seconds pendulums were swung, and interchanged at intervals. The final result taking into account the ellipticity and rotation of the earth is A =6.565.

Von Sterneck's Experiments.—(Mitth. des K.U.K. Mil. Geog. Inst. zu Wien, ii., 1882, p. 77; 1883, p. 59; vi., 1886, p. 97.) R. von Sterneck repeated the mine experiment in 1882-1883 at the Adalbert shaft at Pribram in Bohemia and in 1885 at the Abraham shaft near Freiberg. He swung two invariable half seconds pendu lums simultaneously, one at the surface, and the other below, interchanging them at intervals. Von Sterneck introduced a most important improvement by comparing the swings of the two invariable pendulums with the same clock which by an electric circuit gave a signal at each station each second. This method eliminated clock rates and began a new era in the determination of local variations of gravity. The values which von Sterneck ob tained for L1 were not consistent, but increased with the depth of the second station, probably due to local irregularities in the strata which could not be directly detected.

All the experiments to determine A by the attraction of natural masses are open to the serious objection that we cannot determine the distribution of density in the neighbourhood with any ap proach to accuracy. The experiments with artificial masses next to be described give much more consistent results, and the experi ments with natural masses are now only of use in showing the existence of irregularities in the earth's superficial strata when they give results deviating largely from the accepted value.

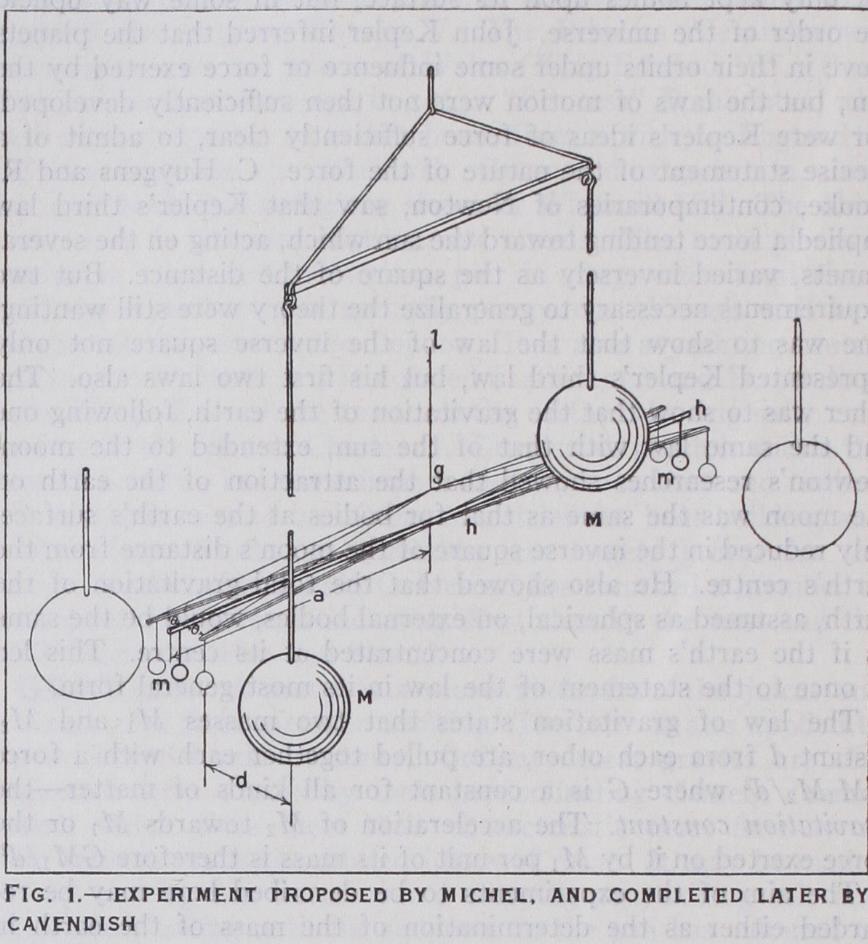

ii. Determination of the Attraction Between Two Arti ficial Masses.—Cavendish's Experiment.—(Phil. Trans., 1798, p. 469.) This celebrated experiment was planned by the Rev. John Michell. He completed an apparatus for it but did not live to begin work with it. After Michell's death the apparatus came into the possession of Henry Cavendish, who largely reconstructed it, and in 1797-1798 carried out the experiment. The essential feature of it consisted in the determination of the attraction of a lead sphere 12 in. in diameter on another lead sphere 2 in. in diameter, the dis tance between the centres being about 9 in., by means of a torsion balance. Fig. 1 shows how the experiment was carried out. A tor sion rod hh 6 ft. long, was hung by a wire lg. From its ends de pended two lead balls mm each 2 in. in diameter. The position of the rod was determined by a scale fixed near the end of the arm, the arm itself carrying a vernier moving along the scale which was viewed by a distant telescope. The torsion balance was enclosed in a case and outside this two lead spheres each 12 in. in di ameter hung from an arm which could turn round an axis in the line of gl. Suppose that first the spheres are placed so that one is at a distance d in front of the left hand ball m and the other is the same distance behind the right hand ball m. The two will conspire to pull the balls so that the left end of the rod moves for ward. Now let the big spheres be moved round so that one is in front of the right ball and the other behind the left ball. The pulls are reversed and the left end moves backward. The angle 20 be tween its two positions is (if we neglect cross attractions of right sphere on left ball and left sphere on right ball) four times as great as the deflection of the rod due to the approach of one sphere to one ball. The work of Cavendish was undoubtedly very accurate for a pioneer experiment and was not really improved upon until about a century later. After making various corrections the result obtained is A = Reich's Experiments.--In 1838 F. Reich published an account of a repetition of the Cavendish experiment carried out on the same general lines, though with somewhat smaller apparatus. ( Ver suche caber die mittlere Dichtigkeit der Erde mittelst der Dreh wage, Freiberg, 1838 ; "Neue : Versuche mit der Drehwage," Leip zig Abh. Math. Phys. i., 1852 p. 383.) The chief differences con sisted in the methods of measuring the times of vibration and the deflection, and the changes were hardly improvements. His re sult after revision was A == In 1852 he published an account of further work giving as result A = 5.58.

Baily's Experiment.—In 1841-1842 Francis Baily made a long series of determinations by Cavendish's method and with appa ratus nearly of the same dimensions (Memoirs of the Royal Astron. Soc. xiv.) . The attracting masses were 12 in. lead spheres and as attracted balls he used various masses, lead, zinc, glass, ivory, platinum, hollow brass, and finally the torsion rod alone without balls. The suspension was also varied, sometimes con sisting of a single wire, sometimes being bifilar. There were systematic errors running through Baily's work, which it is im possible now wholly to explain. These made the resulting value of 0 show a variation with the nature of the attracted masses and a variation with the temperature. His final result 0 = is not of value compared with later results.

Boys' Experiment.—Professor C. V. Boys having found that it is possible to draw quartz fibres of practically any degree of fineness, of great strength and true in their elasticity, determined to repeat the Cavendish experiment, using his newly invented fibres for the suspension of the torsion rod. (Phil. Trans. A., 1895. pt. i., p. i.). He began by an inquiry as to the best dimen sions for the apparatus, and concluded that these should be re duced until further reduction would make the linear quantities too small to be measured with exactness, for reduction of the dimensions enables variations in temperature and the consequent air disturbances to be reduced, and the experiment in other ways becomes more manageable. Professor Boys took as the exact ness to be aimed at 1 in I o,000. He further saw that reduction in length of the torsion rod with given balls is an advantage. Boys avoided difficulties due to the attraction of the second at tracting sphere by suspending the balls from the ends of the torsion rod at different levels and by placing the attracting masses at these different levels. Fig. 2 represents diagrammati cally a vertical section of the arrangement. The torsion rod was a small rectangular mirror about 2.4 cm. long. From the sides of this mirror gold balls were hung by quartz fibres at levels dif fering by I 5 cm. The attracting masses were lead spheres, about I I cm. in diameter and weighing about 7.4 kgm. each, so arranged that the moment of the attrac tion was a maximum. The tor sion rod mirror reflected a dis tant scale by which the deflec tion could be read. The time of vibration was recorded on a chronograph. The result of the experiment, probably the best yet made, was A= G=6.658X Braun's Experiment.—In 1896 Dr. K. Braun S.J., gave an account of a very careful and excellent repetition of the Caven dish experiment with apparatus much smaller than that used in the older experiments, yet much larger than that used by Boys. (Denkschr. Akad. Wiss. Wien. math. natures. Cl. 64, p. 187, 1896.) A notable feature of the work consisted in the suspen sion of the torsion apparatus in a receiver exhausted to about 4 mm. of mercury, a pressure at which convection currents almost disappear while radiometer forces have hardly begun. The at tracted balls weighed S4 gm. each and were 25 cm. apart. The attracting masses were spheres of mercury each weighing 9 kgm.

and brought into position outside the receiver. Braun used both the deflection method and the time of vibration method sug gested to Reich by Forbes. The methods gave almost identical results and his final values are to three decimal places the same as those obtained by Boys.

G. K. Burgess's Experiment.--This was a Cavendish experi ment in which the torsion system was buoyed up by a float in a mercury bath. (Theses presentees a la f aculte des sciences de Paris pour obtenir le titre de docteur de l'universite de Paris, 1900 The attracted masses could thus be made large (2 kgm.) , and yet the suspending wire could be kept fine. From the centre of the beam depended a vertical steel rod with a varnished copper hollow float at its end, entirely immersed in mercury covered with dilute sulphuric acid to remove irregularities due to varying surface tension acting on the steel rod. The size of the float was adjusted so that the torsion fibre of quartz 35 cm. long had only to carry a weight of 5 to io gm. The results gave A= 5.55 and G = 6.64 X Eotvos's Experiment.—In the course of investigations on local variations of gravity by means of the torsion balance, R. Eotvos devised a method for determining G somewhat like the vibra tion method used by Reich and Braun (Ann. der Physik and Chemie, 1896, 59, P- 354)• Two pillars were built up of lead blocks 3o cm. square in cross section, 6o cm. high and 3o cm. apart. A torsion rod somewhat less than 3o cm. long with small weights at the ends was enclosed in a double-walled brass case of as little depth as possible, a device which secured great stead iness through freedom from convection currents. The suspen sion was a platinum wire about 15o cm. long. The torsion rod was first set in the line joining the centres of the pillars and its time of vibration was taken. Then it was set with its length perpendicular to the line joining the centres and the time again taken. From these times Eotvos was able to deduce the pro visional value G = 6.65 X whence 0= Wilsing's Experiment.—We may perhaps class with the Caven dish type an experiment made by J. Wilsing, in which a vertical "double pendulum" was used in place of a horizontal torsion system (Publ. des astrophysikalischen Observ. zu Potsdam, 1887, No. 22, vol. vi. pt. ii. ; pt. iii. p. 133) . Two weights each 54o gm. were fixed at the ends of a rod I metre long, supported so that it could vibrate about a vertical position. Two attracting masses, cast-iron cylinders each 325 kgm., were placed, say, one in front of the top weight on the pendulum and the other behind the bottom weight, and the position of the rod was observed in the usual mirror and scale way. Then the front attracting mass was dropped to the level of the lower weight and the back mass was raised to that of the upper weight, and the consequent deflection of the rod was observed. The result obtained was A = 5.579 iii. Comparison of the Earth Pull on a Body with the Pull of an Artificial Mass by Means of the Common Bal ance.—The principle of the method is as follows : Suppose a sphere of mass m and weight w to be hung by a wire from one arm of a balance. Let the mass of the earth be E and its radius be R. Then w = Now introduce beneath m a sphere of mass M and let d be the distance of its centre from that of in. Its pull in creases the apparent weight of m say by ow. Then 8w = Dividing we obtain 8w/w = whence E = and since g = G can be found when E is known.

Von Jolly's Experiment (Abhand. der k. bayer. Akad. der Wiss.

2 Cl. xiii. Bd. I. Abt. p. 157, and xiv. Bd. 2 Abt. p. 3). In the first of these papers Ph. von Jolly described an experiment in which he sought to determine the decrease in weight with in crease of height from the earth's surface. Von Jolly fixed a bal ance at the top of his laboratory and from each pan depended a wire supporting another pan 5 metres below. Two i-kgm. weights were first balanced in the upper pans and then one was moved from an upper to the lower pan on the same side. A gain of 1.5 mgm. was observed after correction for greater weight of air displaced at the lower level. The inverse square law would give a slightly greater gain and the deficiency was ascribed to the configuration of the land near the laboratory.

In the second paper a second experiment was described in which a balance was fixed at the top of a tower and provided as before with one pair of pans just below the arms and a second pair hung from these by wires 21 metres below. Four glass globes were prepared equal in weight and volume, thus eliminating air cor rections. Two of these were filled each with 5 kgm. of mercury and then all were sealed up. The two heavy globes were then placed in the upper pans and the two light ones in the lower. The two on one side were now interchanged and a gain in weight of about 31.7 mgm. was observed. Then a lead sphere about 1 metre diameter was built up under one of the lower pans and the experiment was repeated. Through the attraction of the lead sphere on the mass of mercury when below, the gain was greater by 0.589 mgm. This result gave A = 5.692.

Experiment of Richarz and Krigar-Menzel.—In 1884 A. Konig and F. Richarz proposed a similar experiment which was ulti mately carried out by Richarz and O. Krigar-Menzel (Anhang zu den Abhand. der k. preuss. Akad. der Wiss. zu Berlin 1898). In this experiment a balance was supported somewhat more than 2 metres above the floor and with scale pans above and below as in von Jolly's experiment. Weights each 1 kgm. were placed, say, in the top right pan and the bottom left pan. Then they were shifted to the bottom right and the top left, the result being, after corrections for change in density of air displaced through pressure and temperature changes, a gain in weight of mgm. on the right due to change in level of 2.2628 metres. Then a rectangular column of lead 210 cm. square cross section and 200 cm. high was built up under the balance between the pairs of pans. On repeating the weighings there was now a de crease on the right when a kgm. was moved on that side from top to bottom while another was moved on the left from bottom to top. This decrease was 0.1211 mgm. showing a total change due to the lead mass of = 1.3664 mgm. and this is obviously f our times the attraction of the lead mass on one kgm. The changes in the positions of the weights were made automatically. The results gave A = 5.05 and G= 6.685X Poynting's Experiment.—In 1878 J. H. Poynting published an account of a preliminary experiment on the same lines as that of von Jolly but on a much smaller scale, which he had made 'to show that the common balance was available for gravita tional work (Phil. Trans., vol. 182, A, 1891, p. 565). In 1891 he gave an account of the full experiment carried out with a larger balance and with much greater care. The balance had a 4 f t. beam. The scale pans were removed, and from the two arms were hung lead spheres each weighing about 20 kgm. at a level about 120 cm. below the beam. The balance was supported in a case above a horizontal turn-table with axis vertically below the central knife edge, and on this turn-table was a lead sphere weigh ing 150 kgm. the attracting mass, and at double the distance from the centre, a second balancing weight. The centre of the larger sphere was 3o cm. below the level of the centres of the hanging weights. The turn-table could be rotated between stops so that the attracting mass was first immediately below the hanging weight on one side, and then immediately under that on the other side. After all corrections the results gave A = 5.493 and .

General Remarks.

The earlier methods in which natural masses were used have disadvantages as already pointed out, which render them now quite valueless. Of later methods the Cavendish appears to possess advantages over the common bal ance method in that it is easier to ward off temperature varia tions, and so avoid convection currents, and probably less diffi cult to determine the actual value of the attracting force. For the present the values determined by Boys and Braun may be accepted as having the greatest weight and we therefore take Mean density of the earth = 5.527 Constant of gravitation G = 6.658 X Probably A = 5.53 and G= 6.66X are correct to 1 in Soo.The Intensity of Gravity.—Measurements of the force of gravity have long been made by means of the pendulum, and prior to the middle of the 18th century, a small weight sus pended by a thin thread was usually employed. The length was adjusted so that the pendulum vibrated a little faster or slower than the pendulum of a clock, and observations were made by the method of coincidences. Later, the clock pendulum itself was used for the measurement of gravity, and a pendulum of this type was used on Captain Cook's voyage round the world.

About the year 1818, Captain Henry Kater employed the in variable pendulum for determining the variation in the length of the pendulum vibrating seconds at the principal stations of the Trigonometrical Survey of Great Britain (Phil. Trans. 1819, p. 337). For many years this type of pendulum was widely used, until the introduction of the half seconds pendulum.

In 1817 Kater introduced his compound reversible pendulum, which was based on the theorem of Huygens, that the centres of suspension and oscillation of a compound pendulum are recip rocal (Phil. Trans. 1818, p. 33) . The pendulum was fitted with two sets of knife-edges so arranged that the period of vibration was the same about both of them. When this adjustment had been made the distance between the knife ,;dges was equal to the length of the simple pendulum of the same period. The length of the seconds pendulum was then obtained by dividing by the square of the period expressed in seconds, while the absolute value of the intensity of gravity could be determined from measurements of the distance between the knife edges, and the period of vi bration.

A great advance in gravity apparatus occurred in 1882 when von Sterneck introduced the quarter-metre invariable pendulum which beat half-seconds, and was more readily protected from all extraneous influences than the larger and more cumbersome equipment. The apparatus now usually employed comprises a set of three one-quarter-metre invariable pendulums with agate knife edges, arranged to swing on three separate agate planes, together with a dummy or temperature indicating pendulum. These pendulums are swung within an evacuated air-tight double walled metal chamber.

The agate planes are carefully levelled by means of two small pendulums carrying levels in their heads, and the three invariable pendulums are then mounted in the three supporting V's. Light, reflected from the mirrors of the two side pendulums, is deflected through a window in the cover into the observing tele scope, by means of two prisms situated near the centre, while the thermometer is visible through a second window.

A flash apparatus enables coincidences to be observed between the swinging pendulum and a clock or chronometer, an electro magnet in circuit with which operates a shutter at the end of each second.

The use of brass pendulums rendered a temperature correction of the greatest importance, and on account of the magnitude of this correction, stations have always been set up in a room of a building in order to reduce considerably the large temperature fluctuations that would otherwise occur.

On the suggestion of Lenox-Conyngham, invar pendulums have been employed with success, and the troublesome temperature correction practically eliminated.

A modification of the apparatus used by Meinesz in his deter minations of gravity at sea was made in 1926 for the Cambridge School of Geodesy. In this apparatus, an airtight and partially evacuated rectangular chamber encloses a support carrying three invar half-second pendulums, mounted in a row with their knife edges parallel, so that they oscillate in the same plane. Each pen dulum is fitted with a knife-edge of stellite, firmly wedged into the head, the central portions of which are polished to form mirrors. Light proceeding from a distant lamp is reflected first to one of the outer pendulums, then to the middle one and finally to the eye or the camera. The beam of light will oscillate up and down as though reflected by a hypothetical pendulum, the phase angle of which is always equal to the difference between the phase angles of the two actual pendulums. This difference is undisturbed by horizontal accelerations which affect the chamber as a whole, and the instrument can thus be used in cases where a perfectly stable platform is not available. Intermittent illumination is pro vided each second by means of a shutter operated electrically from a standard clock, and the resulting record becomes a sine curve, the amplitude and period being the same as those of the hypo thetical pendulum.

Measurement of Gravity at Sea.

A number of attempts have been made to determine gravity at sea, and it is now possible to make these measurements with a degree of accuracy compa rable with that obtainable on land. Early in the present century Hecker (Zentralbureau der internationalen Erdmessung, 1903, 1908, and 1910) endeavoured to compare the pressure as given by a hypsometer, with that indicated by a mercury barometer, while in another method he observed the height of a sealed mercury barometer.Difficulties were encountered due to the ship's oscillatory mo tion, which gave rise to "pumping" of the mercury in the ba rometers and so rendered the results to some extent unreliable. Trouble was also experienced with the hypsometer thermometers, probably as a result of repeated boiling for extended periods.

In 1914 when the British Association visited Australia, Duffield (Proc. Roy. Soc. 1916) made determinations of gravity at sea dur ing the voyages out and home, by means of 3 apparatuses designed respectively to measure gravity, (a) by means of a gravity ba rometer, (b) by means of photographic registering barometers of Hecker's design, (c) by a comparison of readings of mercury and aneroid barometers of special design.

Although the last named method yielded results which seemed promising, it suffered from the disadvantage of using barometers which were open to the atmosphere, and as experiments indicated unsuspected difficulties with such instruments this method was discontinued.

Subsequent voyages in 1922 and 1923 enabled Duffield (Geoph. Supplement, Roy. Astron. Soc. 1924, p. 161) to make determina tions with new instruments including one designed to give a con tinuous record during the voyage. As a result of this work Duf field concluded that in general the value of gravity decreases as the depth of the water increases.

More accurate determinations of gravity at sea were made by Dr. F. A. Vening Meinesz (Geog. Journ., June p. 5o1), on board the submarine K. II. of the Royal Dutch Navy during a voyage from Holland to Batavia in 1923. The apparatus employed was the half-second invariable pendulum apparatus of the Von Sterneck type, fitted with four isochronous pendulums suspended from the same plate, and arranged to oscillate in opposite phases, two by two, in planes at right angles. Their oscillations were re corded photographically, and when the apparatus was displaced from the vertical, as by the motion of the ship, the rays of light reflected from the mirrors of the two opposing pendulums were found to diverge vertically. The pendulums were of brass, which led to difficulties in connection with their large temperature cor rections.

Gravity observations were made at 31 points and the average anomaly for all the stations is o-012 dyne by the Bowie formula, while for 1 o stations in the Indian Ocean the average anomaly is 0.009 dyne.

Meinesz made further investigations in 1926 on a second sub marine voyage to Java with an improved apparatus (Geographical Journal, 1928, p. 144). This new apparatus contained 3 prac tically isochronous pendulums swinging in the same plane as in the Cambridge apparatus and combined in twos for the elimination of disturbances due to horizontal accelerations. The principle of the method is, not to record each pendulum separately, but to get at once the difference of their angles of elongation. The resulting records have the same appearance as that of a single pendulum undisturbed by horizontal accelerations. The apparatus was sup ported in double gimbals in order to avoid sliding of the pendu lums due to the pitching of the vessel, and in this way bigger angular deviations of the boat could be tolerated.

As a result of this voyage, Meinesz found that over the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, there are excesses of gravity extending over large areas, which, it has been pointed out, may be caused par tially by a depression of the geoid with regard to the spheroid. It is not likely however that the excess resulting from this cause will be more than a small fraction of the positive anomalies that have been found, and it is improbable that the anomalies can be wholly explained in this way.

In general, the results obtained at sea give the impression of greater regularity than those obtained on land, as may be expected from the fact that the upper layer of water immediately below the instrument is homogeneous, and the disturbing masses in the solid crust are farther away from the station. The gravity results obtained by Meinesz compel us to accept extensive disturbances of isostatic equilibrium, and until the value of gravity is known with reasonable accur acy over the whole surface of the earth, it will be practically impossible to decide whether these disturbances are located only in the earth's crust, or whether there are also deep-seated anomalies.

Local Variations of Gravity.

Pre vious to 1888 researches on gravity were confined almost exclusively to investiga tions with the pendulum and the bubble level, but Eotvos (Ann. der Phys. and Chem. B59, 1896, p. 354) followed a new line, and endeavoured to measure the variation of the force of gravity in the vicinity of a point, or more exactly to determine the derivatives of its components. As these variations are extremely small in comparison with the total force, Eotvos concluded that the method to be em ployed should measure the differences of gravity directly rather than the force of gravity itself, and he designed a torsion balance which was capable of determining these variations with a con siderable degree of accuracy. This instrument, fig. 3, differs' from the earlier Cavendish balance in that it consists of a light horizontal beam, which supports at its extremities two weights, at different vertical heights, the whole being carried on a very fine torsion wire and enclosed in a double or treble-walled metal case which can be rotated about a vertical axis. A mirror attached to the centre of the beam enables its position to be observed by means of a scale and tel escope, or by an equivalent optical system.In the instrument made by Suss, obser vations are taken visually, and the instru ment is rotated by hand to the next azi muth position of ter each reading, but in other types, e.g., Bamberg and Oertling, fig. 4, the observations are recorded photo graphically, and the instrument rotated into the next azimuth mechanically.

In order to reduce the dimensions of the instrument, without reducing the sensi tivity unduly, or employing very thin wires, Schweydar introduced a Z-shaped beam, having one weight rigidly fixed above and the other below the plane of the beam. A reduction in the length of the torsion wire enables the height of the instrument to be reduced to 120 cm., the centre of gravity of the suspended system remaining 7o cm.

above the ground as in the larger model.

By redesigning the beam system so as to be totally irresponsive to curvature ef fects, Shaw and Lancaster-Jones have in troduced the gravity gradiometer, a single beam instrument by which the gradient may be determined from only three observa tions. The suspended system consists of a series of masses arranged in plan at the apices of a regular polygon, one mass being mounted well above the beam on a rigid light support, instead of being sus pended below, and the remaining masses fixed directly to the beam. The height of the instrument is thus reduced considerably, while a reduction in the length of the beam to 4.5 cm. results in more rapid operation and in increased compactness and portability of the instrument.

If U is the potential of the gravitational force, na the scale reading of the beam after coming to rest in the azimuth position a, fa the scale reading corresponding to no torsion on the wire, D the distance of the scale from the mirror, K the moment of inertia of the suspended system, m the mass of the lower weight suspended at a distance h below the beam, and at a horizontal distance l from the axis of suspension, r the torsion coefficient of the suspension wire, and x, y, and z the axes horizontally along the beam, perpendicular to it, and vertically downwards re spectively, it can be shown that In this equation the five quantities a, U,, UyZ and U.Z are unknown factors, so that by taking readings of na (the posi tion of equilibrium of the beam) in five different azimuth set tings, these factors can be determined from the resulting five equations.

By using two beams placed side by side and oriented oppositely, another unknown value of n is introduced, making six unknowns in all, but as for each setting of such a double instrument, two jeadings are made, one on each beam, it is possible to obtain a complete solution by taking observations in three azimuth set tings of the instrument, so that the speed of operation is thus increased.

The magnitudes U5Z and are the components of the gravity "gradient" in the north and east directions respectively, and represent the increase, per unit distance in the horizontal plane in these respective directions, of the vertical component of gravity. The maximum "gradient of gravity" is the resultant of these components, its value being and its direction is given by tan µ = The other two magnitudes and give the "curvature value," or the deviation of the level surface of gravity from the spheroid. This is measured by the difference of the reciprocals of the principal radii of curvature — and — , pi being the minimum and p2 the maximum radius P1 P2 of curvature, where A is the angle between the plane of principal curvature and the plane xz. The instrument is extremely sensitive to certain extraneous influences, such as radiation and rapid change of temperature, and precautions are taken to provide adequate protection against these sources of disturbances. The suspended beam system is surrounded by an enclosure consisting of three metallic walls, while the instrument itself is set up in a double walled hut specially designed to be light-proof and thermally insulating. The sensitivity of the instrument is such that the unit chosen for expressing the results and known as the Eotvos Unit (E), is I X ro 9 C.G.S. unit, and the determination of the gradient and curvature values at any station may generally be regarded as accurate to one Eotvos unit (IE). Increased sen sitivity would be readily obtainable if desired but would not be justified on account of the errors resulting from the topographical relief of the ground in the vicinity of the station.

The variation in gravity between the poles of the earth and the equator is registered by this instrument, for by Helmert's 1896 formula sin') C.G.S. units where 4) is the latitude.

From this we find that = 8.15 sin 2p X and = 5. I 5 (1 +cos 24)) X io 9 both of which are measurable by the Eotvos torsion balance, an give rise to "normal" corrections which have to be introduce in every practical field survey, in order to determine the loci anomalies.

The choice of suitable stations is an important consideratior for objects close to the instrument have an appreciable effect a its readings, so that unless a site is chosen free from such "ter rain" irregularities, their effect must be computed from dat obtained by levelling radially to a distance of i oo ft. Levels ar taken in eight directions from the balance station, and the height of the surface above the base of the instrument measured at cer tain fixed distances. The gradient correction is found to decreas far more rapidly with distance than the curvature effect, so that i is determined far more readily, the accurate computation of thy curvature effect in rough or broken country being a matter o great difficulty. The practice of relying on gradient values onl: is increasing, except in flat localities where curvatures can bl employed to advantage. The ground outside the 1 oo ft. boundary but within a radius of r,000 ft. of the station, may be sufficientl! irregular to have an appreciable influence on the Eotvos values a the station, although, owing to the comparative remoteness o these irregularities from the station, their effect, known as th( topographical effect, is usually relatively small. Special correc tions must also be made for such features as embankments, wall and cuttings, in the vicinity of the station. When all the norma and superficial effects have been determined, and the necessar3 corrections made, the resultant values of U and will be due entirely to variations of structure and density belov the ground, and are known as subterranean effects. To enable thes( effects to be interpreted, they are plotted to a suitable scale on plan of the survey, on which the isogams, or lines of equal intensity of gravity, are also plotted.