Guatemala

GUATEMALA, the most populous and the second largest country of Central America. The name was formerly applied to the captain-generalcy of Spain which included not only the five Central American countries, extending southward to approxi mately the present northern border of the Republic of Panama, but also included, to the northward, most of the present Mexican State of Chiapas. Following the independence from Spain in 1821, and the separation of the Central American countries from the Mexican empire of Iturbide two years later, the name Guatemala was applied to the region formerly included in io of the 15 provinces; i.e., Chiapas was retained by Mexico and the provinces of Honduras, San Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica became individual entities, recognized as such even through the various attempts to form a Central American Union out of the five countries. (See CENTRAL AMERICA, where, also, the early history of Guatemala is told.) The origin of the name, Guatemala, is certainly Indian, but its derivation and meaning are undetermined. Some students suggest that the original form was Quauhtematlan (which would indicate an Aztec rather than a Mayan origin, a thing most unlikely) meaning "land of the Eagle," and others hold its origin was Uhatezmala, meaning "Mountain vomiting water," referring to the so-called Volcano of Water, or "Agua" which destroyed Ciudad Vieja (q.v.), the first Spanish capital of the captain-generalcy.

The present republic of Guatemala lies between 42' and 17° 49' N., and 88° 1o' and 92° 3o' W. Its area is approximately sq.m., making it thus slightly smaller than Nicaragua, in claimed extent, although it is possible that the actual area of Guatemala is slightly larger (a monograph issued by the depart ment of commerce of the United States in 1927 puts Nicaragua's area as "some 45,00o sq.m.," and boundary disputes and incom plete surveys make all areas and most population figures extremely "approximate" in Central America). The population of Guatemala is put officially at 2,245,593, or about 49 inhabitants to the square mile; the country has a coast line of about 7o m. on the Carib bean and zoo m. on the Pacific shores. Its boundaries on the north and west, which touch Mexico, were fixed by treaty, finally on May 8, 1899, which set the Suchiate river, from the Pacific in land, as the start of an irregular line which runs generally north westward until it strikes the parallel of 17° 49' N., which it fol lows to the border of Belize or British Honduras. The eastern border, with Belize, follows the meridian of 89° 20' W., southward to the River Sarstoon, which it follows eastward to the Gulf of Honduras on the Caribbean sea ; this boundary was set by the treaty of July 9, The Gulf of Honduras, an arm of the Caribbean, forms the short shoreline of Guatemala on Atlantic waters. The boundary with Honduras on the east is still in dis pute, both countries claiming large areas within the generally accepted limits of the other.

Many efforts have been made to adjust this question, the last, in 1928, under the aegis of the United States, resulting in a temporary agreement. The south-eastern boundary with Honduras is generally accepted by the two countries, and the south-eastern line touching on El Salvador is accepted and marked, chiefly along natural lines.

Physical Description.

Gua temala is divided into five regions —the lowlands of the Pacific coast ; the volcanic mountains of the Sierra Madre; the so-called plateaux immediately north of these; the mountains of the At lantic versant ; the plain of Peten.(I) The Pacific coastal plains extend along the entire southern seaboard, with a mean breadth of 5o m., and link together the belts of similar territory in Salvador and the district of Soconusco in Chiapas, Mexico. This region is now being developed as a tropical agricultural section of considerable importance.

(2) The precipitous barrier of the Sierra Madre, which closes in the coastal plains on the north, is similarly prolonged into Salvador and Mexico. It is known near Guatemala city as the Sierra de las Nubes, and enters Mexico as the Sierra de Istatan. It forms the main watershed between the Pacific and Atlantic river systems. Its summit is not a well-defined crest, but is often rounded or flattened into a table-land. The direction of the great volcanic cones, which rise in an irregular line above it, is not identical with the main axis of the Sierra itself, except near the Mexican frontier, but has a more southerly trend, especially towards Salvador; here the base of many of the igneous peaks rests among the southern foothills of the range. It is, however, impossible to subdivide the Sierra Madre into a northern and a volcanic chain; for the volcanoes are isolated by stretches of com paratively low country; at least 13 considerable streams flow down between them, from the main watershed to the sea. The volcanic cones rise directly from the central heights of the Sierra Madre, above which they tower ; for in reality their bases are, as a rule, farther south, east of Tacana, which marks the Mexican frontier, and is variously estimated at 13,976 ft. and 13,900 ft., and if the higher estimate be correct is the loftiest peak in Central America. The principal volcanoes are—Tajamulco (13,517 ft.) ; Santa Maria (12,467 ft.) which has been in eruption since 1902, after centuries of quiescence, in which its slopes had been overgrown by dense forests; Atilan (11,719), overlooking the lake of that name; Acatenango (13,615), which disputes the claim of Tacana to be the highest mountain of Central America ; Fuego (i.e., "fire," variously estimated at 12,795 ft. and 52,582 ft.), which received its name from its activity at the time of the Spanish conquest; Agua (i.e., "water," 12,139 ft.) so named in 1S41 because it destroyed the former capital of Guatemala with a deluge of water from its flooded crater; and Pacaya (8,39o), a group of igneous peaks which were in eruption in 187o.

(3) The so-called plateaux which extend north of the Sierra Madre are in fact high valleys, rather than table-lands, enclosed by mountains. A better idea of this region is conveyed by the native name Altos or highlands, alhough the section so designated by the Guatemalans includes the northern declivity of the Sierra Madre. The mean elevation is greatest in the west (Altos of Quezaltenango) and least in the east (Altos of Guatemala). A few of the streams of the Pacific slope actually rise in the Altos, and force a way through the Sierra Madre at the bottom of deep ravines. One large river, the Chixoy, escapes northwards towards the Atlantic.

(4) The relief of the mountainous country which lies north of the Altos and drains into the Atlantic is varied by innumerable terraces, ridges and underfalls ; but its general configuration has been compared with the appearance of a "stormy sea breaking into parallel billows." The parallel ranges extend east and west with a slight southerly curve towards their centres. A range called here the Sierra de Chama, which, however, changes its name frequently from place to place, strikes eastward towards British Honduras, and is connected by low hills with the Cockscomb mountains; another similar range, the Sierra de Santa Cruz, continues east to Cape Cocoli between the Polochic and the Sarstoon rivers, and a third, the Sierra de las Minas or, in its eastern portion, Sierra del Mico, stretches between the Polochic and the Motagua. Be tween Honduras and Guatemala the temporarily accepted frontier is that along the Sierra de Merendon.

(5) The great plain of Peten, which comprises about one-third of the whole area of Guatemala, belongs geographically to the Yucatan peninsula, and consists of level or undulating country, covered with grass or forest. Its population numbers less than two per square mile, although many districts have a wonderfully fertile soil and abundance of water. The greater part of this region is uncultivated, and only utilized as pasture by the Indians, who form the majority of its inhabitants, and as a source of chicle, the basis of chewing gum. Peten was for centuries, however, the site of great cities of the later Maya empire and much of the important archaeological work now being done in Central America is going forward in this region. It is also the scene of petroleum prospecting.

Guatemala is well watered, not only on the eastern slopes (as is common along the American continents) but also on the Pacific slope and in the highlands. On the western side of the sierras the versant is short, and the streams, while very numerous, are conse quently small and rapid; but on the eastern side a number of the rivers attain a very considerable development. The Motagua, whose principal head stream is called the Rio Grande, has a course of about 25o m., and is navigable to within 90 m. of the capital, which is situated on one of its confluents, the Rio de las Vacas. It forms a delta on the south of the Gulf of Honduras. Of similar importance is the Polochic, which is about 18o m. in length, and navigable about 20 m. above the river-port of Teleman. Before reaching the Golfo Amatique it passes through the Golfo JJulce, or Lake Izabal, and the Golfete Dulce. A vast number of streams, among which are the Chixoy, the Guadalupe, and the Rio de la Pasion, unite to form the Usumacinta, which in its early stages passes along the Mexican frontier, and then flowing on through Chiapas and Tabasco, falls into the Bay of Campeche. The Chiapas follows a similar course.

There are several extensive lakes in Guatemala. The lake of Peten or Laguna de Flores, in the centre of the department of Peten, is an irregular basin about 27 m. long, with an extreme breadth of 13 miles. In an island in the western portion stands Flores, a town well known as the centre of the archaeological work now being carried on. On the shore of the lake is the stalac tite cave of Jabitsinal, of local celebrity; and in its depths, accord ing to the popular legend, may still be discerned the stone image of a horse that belonged to the conqueror, Hernando Cortes. The Golfo Dulce is, as its name implies, a fresh-water lake, although it is virtually an arm of the Caribbean; comparable on a smaller scale to Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela. It is about 36 m. long, and would be of considerable value as a harbour if the bar at the mouth of the Rio Dulce did not prevent the upward passage of seafaring vessels. As a contrast the lake of Atitlan is a beautiful land-locked basin encompassed with lofty mountains. About 9 m. south of the capital lies the Lake of Amwtitlan (q.v.) with the town of the same name. On the borders of Salvador and Guate mala there is the Lake of Guija, about 20 m. long and 12 broad, at a height of 2,100 ft. above the sea. It is connected by the river Ostuma with the Lake of Ayarza which lies about i,000 ft. higher, at the foot of the Sierra Madre.

The geology, fauna and flora of Guatemala are discussed in the article CENTRAL AMERICA. The bird-life of the country is remark ably rich; one bird of magnificent plumage, the quetzal (Trogon resplendens), has been chosen as the national emblem.

Climate.

The climate is healthy, even on the coasts, where the malarial fever that was so long the curse of the country has been largely conquered by a growing adoption of modern sanita tion. The rainy season in the interior lasts from May to October, but on the coast often continues until December. The coldest month is January, and the warmest is May.The average rainfall is heavy, especially on the Atlantic slope, where the prevailing winds are charged with moisture from the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean sea; at Tual, a high station on the Atlantic slope, it reaches 195 in.; in central Guatemala it is only 27 inches. Towards the Atlantic rain often occurs in the dry season, and there is a local saying near the Golfo Dulce that "it rains 13 months in the year." Fogs are not uncommon. In Guatemala, as in other parts of Central America, each of the three climatic zones, cold, temperate and hot, has its special char acteristics, described in the article on CENTRAL AMERICA.

Natural Products.

The minerals discovered in Guatemala include gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, mercury, antimony, coal, salt and sulphur; but it is uncertain if many of these exist in quanti ties sufficient to repay exploitation. Gold is obtained at Las Quebradas near Izabal, silver in the departments of Santa Rosa and Chiquimula, salt in those of Santa Rosa and Alta Vera Paz. During the I 7th century gold-washing was carried on by English miners in the Motagua valley, and is said to have yielded rich profits; hence the name of "Gold Coast" was not infrequently given to the Atlantic littoral near the mouth of the Motagua.The area of forest has not been seriously diminished except in the west, and still amounted to 2,000 sq.m. in 1925. Besides chicle, and a small quantity of wild rubber of the Castillao elastica, it yields many valuable dye-woods and cabinet-woods, such as cedar, mahogany and logwood. Fruits, grain and medicinal plants are obtained in abundance, especially where the soil is largely of vol canic origin, as in the Altos and Sierra Madre. Parts of the Peten district are equally fertile, but not greatly developed. The vege table products of Guatemala include coffee, cocoa, sugar-cane, bananas, oranges, vanilla, aloes, agave, ipecacur. nha, castor-oil, sarsaparilla, cinchona, tobacco, indigo, chicle, rubber and the wax plant.

Inhabitants.

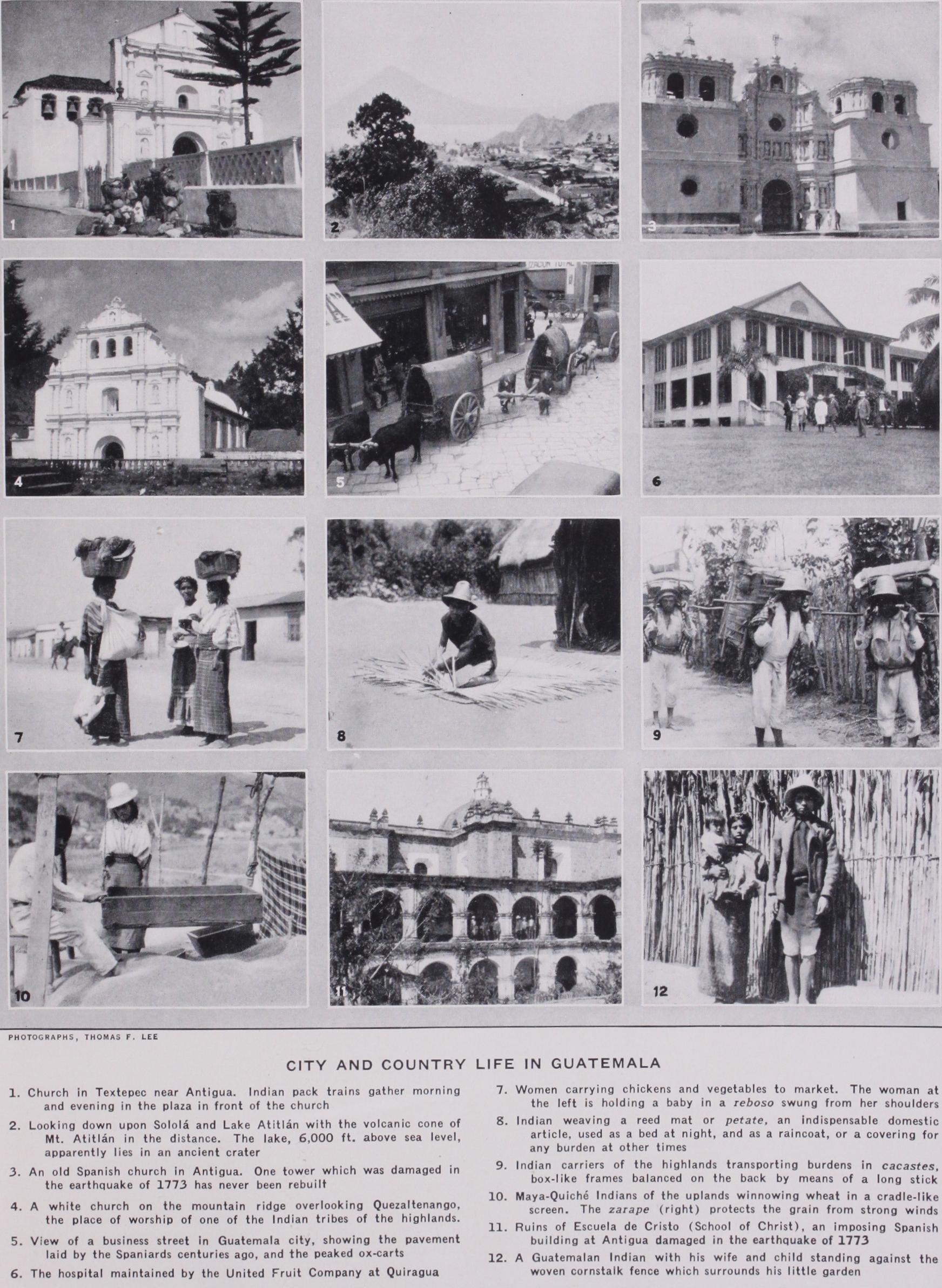

Guatemala's population, 2,004,90o by the 192 i census and placed at 2,245,593 by an official estimate made in is composed of at least 6o% Indian, approximately 30% mixed blood whites and Indians and less than 5 % pure white of Spanish strain, including about i 2,00o Europeans and Americans. The balance, of roughly 5 %, are negroes and mixtures of Indian and negro, the latter proudly calling themselves "Carib Indians" in some sections, and probably, on the Caribbean shores, the descend ants of the original Carib and Mosquito Indians and the slaves brought in by the Spaniards. The pure negro population is now largely if not entirely an importation from the British West Indies, brought in recent years by the fruit companies to furnish the labour for the banana plantations. Prior to the extensive sanita tion of the Caribbean lowlands, chiefly in the beginning by the banana companies, the Indians refused to come down to the fever-infested sections where their traditions, as the ruins of earlier civilizations seem to bear out, hold that vast numbers of their ancestors died in tropical plagues in centuries past.The Indian population of Guatemala is more nearly aboriginal in its habits and life than in any similar section of North or probably of South America. The existent tribes have been only sketchily studied, for the anthropology and ethnology of Central America are still almost untilled scientific soil, although it is known of course that the living Indians of Guatemala come, in general, from the Maya or from the yet older and less highly developed kindred Quiche strains (see MAYA) . The Indian coun try is in the highlands, the "Altos" above described. It is esti mated that at least i8 different Indian languages are spoken in Guatemala, and in the highland hinterland the tribes, with their distinctive dress, still rigorously maintained and distinguishing village from village as well as tribe from tribe, are sharply sep arated from one another in manners and language, Spanish being the only common tongue, and that unknown to thousands. The Governments of Guatemala, from the Spaniards down to to-day, have handled the Indians by converting the caciques, or tribal and village chieftains, into Government officials, and the control by the central Government of the Indian provinces is virtually feudal in form, the representative of the central authority still being a mili tary official, of varying rank, according to the importance of his post. The Indians, however, form the basis of the army, and many pure blooded Indians have risen high in military rank, the common soldier remaining Indian, however, with his loyalty rep resented by his affection for his immediate superiors, a trait which has been of considerable importance in time of threatened revo lution. The barefooted Indian soldier, with his canvas leggings binding his khaki uniform to his bare ankles, remains the basis of Guatemalan Government, so far as the preservation of public order is concerned; and his caciques—dignified Indian chieftains dressed in elaborately embroidered robes, with kilts and tartans of their village and with ornate staffs of office—are the repre sentative of an authority more absolute than that wielded by the white or mixed-blood officer who is nominally the political chief of the area.

The Indians differ but slightly in physical mien, being of dark copper skin, stocky build, with coarse, straight black hair, high cheekbones and low forehead, although the suggestion of the ori ental type comes in more often than in Mexico, and almost as much as in the Indians of the highlands of Bolivia and Peru, in South America. In their tribal life, the Indians are deeply loyal, but outwardly secretive. Nominally belonging to the Roman Catholic faith, they have many strange tribal dances, and the festivals of the church are made the occasion for rites often associated with images either on or quite outside the church altars; an immense folk-lore, with particular reference to witchcraft and disease, has been noted but only partially analysed by local and foreign students.

The Indian, forming the chief labour supply of the country (with the exception of the imported negroes who are almost en tirely confined to the Caribbean littoral) are handled in feudal fashion by the coffee planters and by the officials who must assist them. The abuses of earlier days, in the virtual slavery or peonage on the coffee plantations, have been somewhat ameliorated in recent years, but the wage is still miserably small, the system of debt indenture is widespread, with the Indians evading it by assuming varied Spanish names—their own are so difficult to pro nounce or at least to reduce to paper that the landlords encourage the exchange—or by disappearing from their highland villages when the picking season begins on the coffee plantations. A prac tice growing in use amongst the coffee planters is to purchase estates in the highlands, where the Indians are given free use of the tiny farming sections in the confined plains between the hills, their only obligation being a guarantee to come and work at the coffee picking at regular wages when the landlord calls upon them.

The chief centres of population are the capital, Guatemala city, with about 134,400 people; Antigua, 40,00o; Quezaltenango, 30, 000; Totonicapan, 28,000; Chiquimula, 25,00o; Coban, 27,000; Solola, 17,00o; Esquintla, 13,000; Hueheutenango, I2,000; Retal huleu, 7,000; Puerto Barrios, 2,500; Livingston, 2,500; San Jose, 1,50o; Champerico, 1,500. Most of these towns and cities are described under separate headings.

Political Organization.

The present constitution of Guate mala dates from Dec. II, 1879, although it was preceded by two others, those of 1851 and 1876, following the separation of Guate mala from the Central American Federation. The Government is divided into the three branches, executive, judiciary and legisla ture. Citizenship is determined either by birth in the republic or Guatemalan parentage, and includes nationals of the other Central American republics who are resident in Guatemala, unless they ex pressly elect to belong to the country of their original nationality. Suffrage is limited to males over 21 who have income or liveli hood, and to soldiers over 18. Education is free, compulsory and non-religious. The various guarantees in the constitution may be suspended by the executive in time of crisis, with the approval of the council of ministers. This "suspension of guarantees" is usually loosely translated into English as "putting the country under mar tial law," but is not comparable to this situation, as it means pri marily the temporary strengthening of the police power by making inactive the usual legal subterfuges by which offenders may avoid arrest or escape penalties. The legislative branch of the national Government consists of one chamber only, with one member for every 20,000 inhabitants of the country. The members of this national assembly are elected by popular vote every four years, election of half the body being held biennially. The national as sembly also canvasses the vote for president, and may elect the president, in case there is no majority, from the three leading can didates. It also chooses the two "designates" who are the virtual vice-presidents, and who succeed the president in case he is in capacitated. The assembly also elects five members of the council of State and chooses the permanent commission of seven of its members to act during recess.The executive power rests in the president, who is chosen for six years by popular vote. He appoints his cabinet of six secre taries of State, who are responsible officers, and may speak and vote in the national assembly. With the five members appointed by the assembly and four named by the president, the cabinet forms the council of State, a body with purely advisory functions, but often of great importance. The judiciary consists of a supreme court of five members, six courts of appeal of three members each, and 26 courts of first instance. Judges are chosen by direct popular vote and serve for a term of four years. The country, for purposes of administration, is divided into 23 departments, each presided over by a je f e politico or prefect appointed direct by the president. The municipalities are governed by alcades (or mayors) and councils chosen by direct vote of the people ; these have the power to assess and collect local revenues. The prefect, represent ing the central government, has the authority to amend the ordi nances and enactments of the councils of the towns in his depart ment. The police power is handled both by local constabulary in the towns and by the military, and is generally thoroughly effi cient and effective. There is some public care of the unfortunate but in general eleemosynary work is left to the religious denomi nations, chiefly Roman Catholic.

Education.

Education, while free laical and compulsory, is still far from efficient, the frank estimate of the Government being that only io% of the population can read and write. In 1927 there were 2,761 Government primary schools, and in addition, some 135 private primary schools including the parochial schools and those operated for the children of foreigners. School enrol ment was 103,341 and attendance 77,838 in 1925. On all the plantations where there are more than ten children the owners are by law required to furnish teachers and schools, but this rule is not as generally observed as might be wished. In higher education, there is the University of Guatemala, established in 1918, where courses in law, medicine, engineering, art and music are given, chiefly by means of lectures from the eminent professional men of the capital. There are two institutes for the education of teachers in Guatemala city, one for men with about 500 pupils and one for women with about 300. Similar normal schools are maintained at Quezaltenango and at Chiqui mula. There are 48 professional, normal, secondary and special schools. The National library contains about 20,000 volumes.

Religion.

The prevailing form of religion in Guatemala is Roman Catholic, the church claiming virtually 90% of the population as communicants.The archbishop of Guatemala is the primate of Central America and the church influence is very powerful. There are some Prot estant missionaries and mission schools. The Indians are theo retically Roman Catholics, but in some regions their religious prac tices are influenced by their not always coherent race memories of idolatrous conditions and practices, and some of the great Christian festivals bring out practices not entirely in accord with the strictest tenets of the church. On the other hand, much of the white population is notably and frankly religious, and while this is somewhat divided on political lines, and the church has at times been accused of opposing the prevailing liberal Government with serious consequences, the religious attitude of the people of the higher classes has not been greatly affected.

Finance.

Guatemala is on a gold basis, the unit of currency being the "quetzal," named after the national bird of Guatemala, and equal in value to the American dollar. The establishment of the gold currency in Nov. 1924 followed years of financial chaos in which the old peso, at one time virtually equal to the present quetzal, dropped almost to 1% of its old value, and the stabiliza tion was finally made on the basis of 6o to 1. The depressed value of the paper peso was traceable to heavy loans made by the execu tive from the local banks, various presidents of the country giving the various banks, in return for the specie taken, the right to issue paper money without the proportionate metallic reserve required by the former laws. The Government loans totalled in value, at the exchange rate at the time of stabilization and the creation of the gold quetzal in 1924, about 180,000,000 paper pesos, but in exchange for this debt there were about 400,000,000 paper pesos, in bank notes, in circulation. The final arrangement of the Gov ernment was the guarantee of these paper pesos at a fixed rate of 6o to the quetzal, and then, on a graduated scale, the retirement of original debt of about (at the agreed rate of exchange) 3,000,00o quetzales. The balance of the paper money in circula tion (about 220,000,000 pesos or about 3,700,000 quetzales) is equally guaranteed by the Government and will in time also be retired, through the operation of the national bank of issue ar ranged in the financial plan. The funds for this conversion have been obtained from the revenues of the country, chiefly through a tax of one quetzal per bag of coffee (of 200 lb.), a tax which through the recent years of high prices for coffee has been easily paid, until the Guatemalan Government is convinced that it will complete its financial stabilization without recourse to a foreign loan. The sole right to issue paper currency is now vested for ten years in the new Government-controlled Banco Central, under a contract dated June 30, 1926.The foreign gold debt of Guatemala was in 1928 less than £2,000,000 sterling, chiefly held in England and Germany, and paying 4% ; the internal debt was approximately the same. The service on the foreign debt in 1926-27 was 242,704.99 quetzales.

The

income of the Federal Treasury in the fiscal year 1926-27 was 1 1, quetzales, and the expenditures during the same period 11,217,358.98 quetzales. Of the receipts, were from import duties; Q2,237,468.98 from export duties; from the liquor tax; Q858,380.75 from miscellane ous taxes ; Q646,044.09 from consular fees; Q 120, 210.64 from, and for, special funds; Q292,813.77 from the Federal telegraphs; Q202,213.31 from the post office; Q280,042.43 profits from the coinage of the new silver put into circulation; Q89,741.98 from certain payments by the banks. The telegraphs and the post office were the only branches of the Government which showed a loss.

Guatemala is well supplied with banks, the strongest, outside the new central bank of issue, being the six banks which formerly had the right of issue through their contracts with the Government mentioned above, namely, the Banco de Guatemala, International Bank of Guatemala, American Bank, Banco del Occidente, Banco Agricola Hipotecano and Banco Colombiano. Private banks in clude branches of the Anglo-South American Bank, the Notte bohm Banking Corporation, Pacific Bank and Trust Company, Schlubach Sapper and Co. and Rosenthal e Hijos.

Defence.—The Guatemalan army is theoretically made up of all the males of the white and mixed population, who are subject to call to arms from the age of 18 onward. Under the treaty of Feb. 7, 1923, with the other Central American countries, the army contains 5,200 officers and men, the officers being the product of the official military schools where excellent instruction and train ing are given, and the rank and file of the army largely made up of Indians. The effective strength of the army subject to call is 57,00o active and 30,000 reserve. The army budget in 1926-27 was Q2,191,711.62.

Industries.

Guatemala's chief industry is coffee growing, with an annual production of about 1 oo,o00,000 lb., bananas coming second with some 6,000,000 bunches and about 20,000,000 lb. of sugar as the third most important item. Cotton is grown in some sections, with a total production of about 3,o0o,000 lb., and there are cotton mills, using the native and imported cotton to make goods of the cheaper qualities to meet local demands. Wheat is grown in the highlands, and there are several flour mills. Other industries include breweries, distilleries, shoe factories, tanneries, etc. There has been some mining, but no great returns come from this industry. Various exploring parties have been seeking petro leum, and concessions for drilling have been taken up by some of the great foreign companies. Under the new petr3leum laws, oil concessions run for 4o years and the sole tax is io% of the gross oil taken out in two territories near the sea-coast and 8% in two other deliminated sections further from transportation.

Commerce.

Guatemala exports coffee,, sugar and bananas, and some cotton, the total exports of these commodities being approx imately equal to the production noted above, with the exception of cotton, whose exports are a small item as yet. The imports of Guatemala consist chiefly of machinery, including automobiles, luxuries of various sorts and fabrics of cotton, silk and wool, shoes and furniture. Exports average around Q 15,000,000 with imports of QI i,000,000 to Q12,000,000, the United States taking over 85% of the exports and furnishing 6o% of the imports, Germany being second in the exports taken and Great Britain second as a source of Guatemalan imports.

Communications.

The railways of Guatemala are all con trolled by the International Railways of Central America, an American company headed by Minor C. Keith and operating S97 m. of railway, in addition to the Salvador branch from Zacapa, opened in 1929, and the lines in Salvador owned by the same company. The International railways cross Guatemala from Puerto Barrios on the Caribbean sea to San Jose on the Pacific, the capital, Guatemala, being on the main line 198 m. from Puerto Barrios and 75 m. from San Jose. From the junction at Santa Maria, near San Jose, the line to the Mexican border, paralleling the Pacific, turns off ; this line has a branch from Retalhuleu to the Pacific port of Champerico. A considerable portion of the mileage of the Interna tional railways on the eastern side cover the banana plantations belonging to or leased by the United Fruit Company. This corn pany also has extensive railways of its own in the plantations. An electric line, from the International railways to Retalhuleu and Quezaltenango, is also in partial operation.The telegraph lines of the Government cover the country ef fectively, and in addition there are three wireless stations, at Guatemala, Quezaltenango and Puerto Barrios. The telephone sys tem in Guatemala city is good, and there are long distance lines controlled by the fruit companies. The All America cables enter from the Pacific side, at San Jose, and are available to the country via the Government telegraph lines.

The highway development in Guatemala is still in its early stages, although the road from Guatemala to Antigua is open virtually all the year, as is the new overland highway, recently graded, which links Guatemala with San Salvador, the capital of the neighbouring republic of El Salvador. A highway from Retalhuleu to Quezaltenango and on to Solola is also passable most of the year, and there are many other highways, but there are no hard surfaced roads in Guatemala, and broken rock is used only where necessary. The beginnings that have been made indicate, however, an extensive interest, and the funds expended have been wisely and effectively invested. The growing importations of auto mobiles and their increasing use are having a direct effect on the public interest in road building.

History.

The history of Guatemala, as linked with Central America in general, has been given under that heading. Rafael Carrera (1814-65), the great conservative president of Guatemala, was the leader under whom the separate republic of Guatemala was formed after the dissolution of the Central American Federa tion, in 1839. In 1851, Carrera defeated the Federalist forces from Honduras and Salvador at La Arada, near Chiquimula, close to the Honduran frontier, and the same year the new constitution was promulgated and Carrera elected president, an office which in 1854 was conferred upon him for life. The struggle for the domination of Central America went on, with Carrera as the sup porter of the conservative and clerical forces. He was aided at one time by Costa Rica and Nicaragua, and occupied San Salvador in the course of a campaign which resulted in his becoming the dominant figure and virtual power behind the Government of all five of the Central American countries. Carrera died in office, being succeeded by General Cerna, in April, 1865. The liberal elements of Guatemala grew in strength after Carrera's death and in May, 1871, President Cerna was deposed and later the arch bishop and the Jesuits were exiled. Justo Rufino Barrios 85), the liberal leader who had directed the opposition to the conservatives, was elected liberal president of Guatemala in 1873. He was a militant advocate of the Central American Union and sought to impose it by arms when his peaceful overtures failed. He invaded Salvador in 1885, met his former friend President Zaldivar of Salvador, in battle and Barrios fell in the contest, on April 2, 1885. He was succeeded by Gen. Manuel Barillas, who quickly made peace with Salvador and the other three Central American countries.General Jose Maria Reina Barrios was elected president in 1892, re-elected in 1897 and assassinated on Feb. 8, 1898. Succeeded by Vice-President Morales, the power passed, by election to Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1857-1924) in the fall of the same year. Estrada Cabrera ruled, continued in office by frequent re-elections, until April, 1920, when he was forced to resign in the face of a revolutionary movement which had spread to the national as sembly. Estrada Cabrera, as dictator of Guatemala, was respon sible for many improvements in the line of education, railways and industrial development, but was bitterly opposed by a large proportion of the substantial elements of the country. In 1906, his predecessor in the presidency, Gen. Manuel Barillas, invaded Guatemala, and soon Salvador, Costa Rica and Honduras were arrayed against Estrada Cabrera, with Nicaragua inactive but unfriendly. The situation was saved by the intervention of the United States and a subsequent meeting of representatives of the five republics in Washington, where the treaties of 1907 were drawn up.

The Unionist movement of 1920 became, in Guatemala, a move ment against Estrada Cabrera, and, as noted, he was forced to resign, after a brief but lively revolutionary campaign, confined solely to the capital. The national assembly, naming Carlos Her rera, a conservative and unionist, as first designate, he was ele vated to the presidency. A man of culture and wide experience, President Herrera began the rehabilitation of the country, and the restoration of the capital from the ruin following the earthquake of 1917-18. On Oct. io, 1921, he signed, with Honduras and Sal vador, the pact for the Central American Union.

On Dec. 7, 1921 the liberals overthrew Herrera and in March following Gen. Jose Maria Orellana was elected president. Under his able administration until his death in October 1926, and there after under that of his successor Gen. Lazaro Chacon, the country progressed in stability and peace. But on Dec. 16, 193o the latter was overthrown as a result of a coup d'etat, executed by Gen. Manuel Orellana. Unable to secure recognition from the United States in accordance with the treaty of 1923, Orellana was soon compelled to resign. And in February 1931 Gen. Jorge Ubico, of the Liberal-Progressive Party was elected president for a six year term. Guatemala with the rest of the world suffered from the economic depression, but her government managed to hold its position. In 1933 the long standing boundary dispute between her and El Salvador was finally settled by arbitration. BIBLIOGRAPHY.-C. W. Domville-Fife, Guatemala and the States of Central America (1913) ; A. Caille, Au Pays du Printemps Eternel (1954) ; Dana G. Munro, The Five Republics of Central America (1916) ; J. V. Mejia, Geografia Descriptiva de la Republica de Guate mala (1922) ; Wallace Thompson, Rainbow Countries of Central America (1926). Earlier authorities include Juarros, Compendio de la historia de Guatemala (trans. into English 1823) ; Karl Sapper, Grand zuge de Physikalischen Geographie von Guatemala (1894) ; A. C. and A. P. Maudslay's A Glimpse of Guatemala, and some Notes on the Ancient Monuments of Central America (1899) . Consult reports of the Pan-American Union (Government Printing Office), Washington, and H. M. Stationery Office, for current data on trade, etc. (W. THO.)