Tecture

TECTURE.) Rome.—The development of governmental life under the Roman empire is reflected in its mature types of governmental architecture. The group of gov ernment buildings surrounding the Roman Forum formed, in fact, the earliest prototype of the modern national capitol; its buildings nevertheless, are merely high developments of those of a small city such as Pompeii. There one end of the forum was filled by three buildings with a common facade, the central being the curia or town council chamber, and those at the sides the offices of the duumvirs and the aediles. The purpose of the central building was thus legislative and that of the side units executive. All three are rectangular halls with re cesses or apses at the end. More over, close to this group there is, on one side, an enclosed court which is supposed to have been the comitium or voting place for the citizens. On the other side stood the basilica (q.v.), so that all the functions of government were housed in buildings designed for governmental purposes.

In Rome the details are different and additional elements appear, yet the basic idea is the same. The senate house or Curia, whose walls still stand as the church of S. Adriano (rebuilt by Julius Caesar and Augustus after a fire, rebuilt again by Diocletian after the great fire of A.D. 283), was a rectangle 75 ft. wide and '85 ft. long, probably with columns dividing it in three aisles, and an apsidal tribune at the end, containing a statue of Victory. This senate house was at one end of a large structure ; at the other was a smaller apsidal hall, now the church of S. Martina, and originally the secratarium senates; between the two were two other halls for archives and executive offices. Stairs indicate the presence of a second floor. The whole formed a richly decorated and magnifi cent government building. Close by on the slope of the Capitol hill was the great national archives building known as the Tabu larium, built by Sulla, whose powerful masonry and monumental arcades still overlook the Forum. Across the Forum from the Curia was the Roman treasury, incorporated into the temple of Saturn. The crowded judicial functions were housed in numerous basilicae, especially the Basilica Aemilia and the Basilica Julia.

At the other end of the Forum stood the Regia, the Roman form of the Greek prytaneum, the ritual centre of Roman life and government, and the official residence of the pontifix maximus, closely related to the Atrium Vestae and the temple of Vesta with the never-dying city fire. Thus even in the sophisticated civiliza tion of Rome, government still retained its ancient connection with religious rites, and on ceremonial occasions, even the senate itself was convoked, not in the Curia, but in temples or sacred buildings as in the famous Area Apollonis of Augustus on the Palatine hill. (See ROMAN ARCHITECTURE.) Middle Ages.—The autocracy of the later emperors and the feudal system which followed were not conducive to the develop ment of governmental buildings. It was only with the develop ment of the powerful municipalities of the I2th century that the modern tradition of governmental architecture began. Throughout Europe the reaction against feudalism found expression in the building of town halls in which were centred more and more of the functions that had been scattered through monasteries and feudal castles. At first the town hall was merely a meeting place for citizens, sometimes nothing more than a belfry whose bell was used to call meetings in a public square; but other rooms for offices and storage were soon added, and by the middle of the 12th century, at least in France and Italy, types had become definite. In Italy the Palazzo pubblico resembled the town houses of the wealthy in usually being built around a court and having high, castellated walls. It might serve both as an official building, with meeting halls for governing bodies, and also as a residence for the commanding general. Sometimes, as in Florence, two separate buildings, the Palazzo Vecchio (1298) and the Bargello (1256) were used, the former a town hall, the second the residence of the chief magistrate and the prison. Both of these, like all early Italian town halls, have campaniles or belfries attached. There are other characteristic town halls of the period at Siena and the remarkable Palazzo della Ragione at Padua (II 72-1 219), whose upper hall was made into one room (142o) said to be the largest undivided hall in Europe, 89 ft. wide, 267 ft. long.

The French type usually combined an arcaded market hall on the ground floor with the governmental portion above and a belfry at one side. At S. Antonin there is a town hall of the I2th century in almost perfect preservation. Another I2th century example is that at La Reole. As the power of the municipalities increased, the richness of the town hall grew also, and those at S. Omer, 14th century, and S. Quentin, i6th century, with an elaborate late Gothic façade, show the development. The market hall has been completely forced out and the entire building is devoted to govern mental purposes, and instead of one or two large chambers with a chapel, there now appears a more articulated plan with meeting halls, offices and storage facilities carefully differentiated.

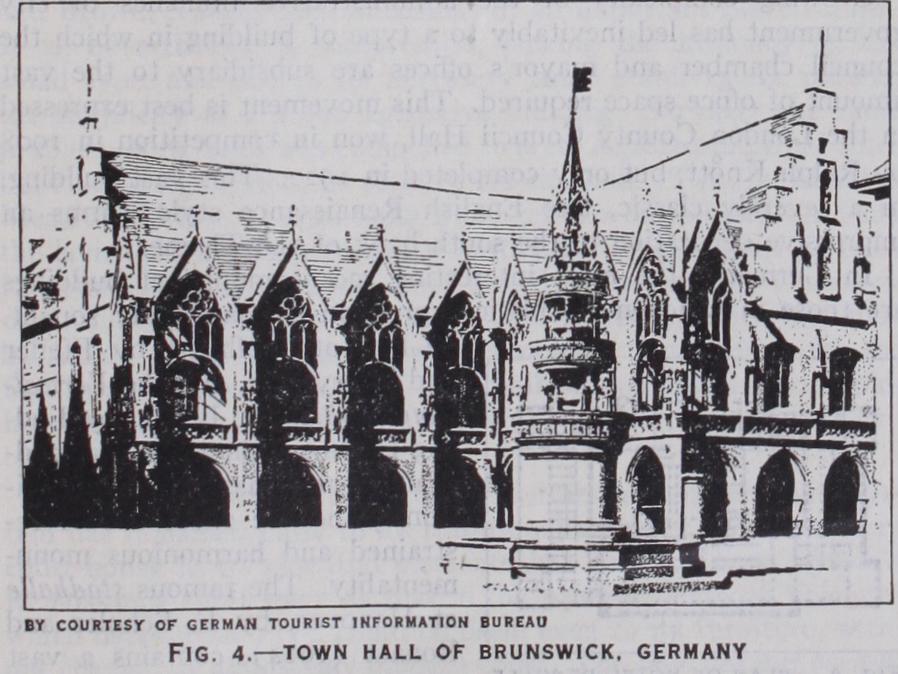

During the 200 years from 140o to i600, the town hall received its greatest development in the dominantly commercial cities of the north. In these a new influence was operative, that of the gild-hall, for the merchants gilds had become closely related to municipal government ; in some cases the governing body of a city was itself termed a gild. Thus the hall of the corporation of the city of London is known as the Gildhall. In some towns of the Low Countries, the town hall and a gild-hall were combined. Thus at Ypres the town hall is also known as the Cloth Hall. This magnificent building (I2oo-1304), is a vast rectangle 5o ft. wide and 462 ft. long. Its arcaded ground floor served as a cloth market, its upper floor contained meeting halls, law courts, banquet halls and municipal offices. The whole formed one of the most monu mental examples of secular Gothic in Europe until it was destroyed in the World War. Other remarkable Flemish examples are those of Arras (finished 1494, belfry I 554) , Louvain (1448-63), Brussels (138o-1442) and Ghent (completed • In Germany the most beautiful town halls are those of Lubeck (i3th century), Tanger munde (1373-78) with remarkable brick Gothic detail, the com plex town hall of Brunswick (14th century) and the simpler 15th century example at Goslar. (See GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE.) Renaissance.—This general type of town hall design continued in use throughout the Renaissance period except in Italy. There the desire for classicism led to the erection of smaller and more elegant single buildings such as the beautiful Palazzo del Con siglio at Verona (c. 150o by Fra Giocondo), whose exquisite early Renaissance polychrome facade was adapted by McKim, Mead and White for the old Herald building in New York, and the equally rich and somewhat similar Municipio of Brescia (c. 1500). Michelangelo's Palazzo del Senatore (1592-98) on the Capitoline hill at Rome is significant in its attempt to give to such an official building an architectural form dominant and monumental, and differing alike from the castellated halls of the middle ages and the delicate early Renaissance of north Italy.

Outside of Italy, where the mediaeval tradition held true, the Renaissance town halls merely clothed in classic dress such build ing types as had been developed before; e.g., the town hall of Bremen (15th century, reconstructed 1609) and the old city hall of Paris (originally built under Francis I. and destroyed in the civil war, 1871). In rebuilding the latter, the old plan was merely enlarged and the old style preserved; the modern tradition of municipal building is thus founded on the mediaeval town hall.

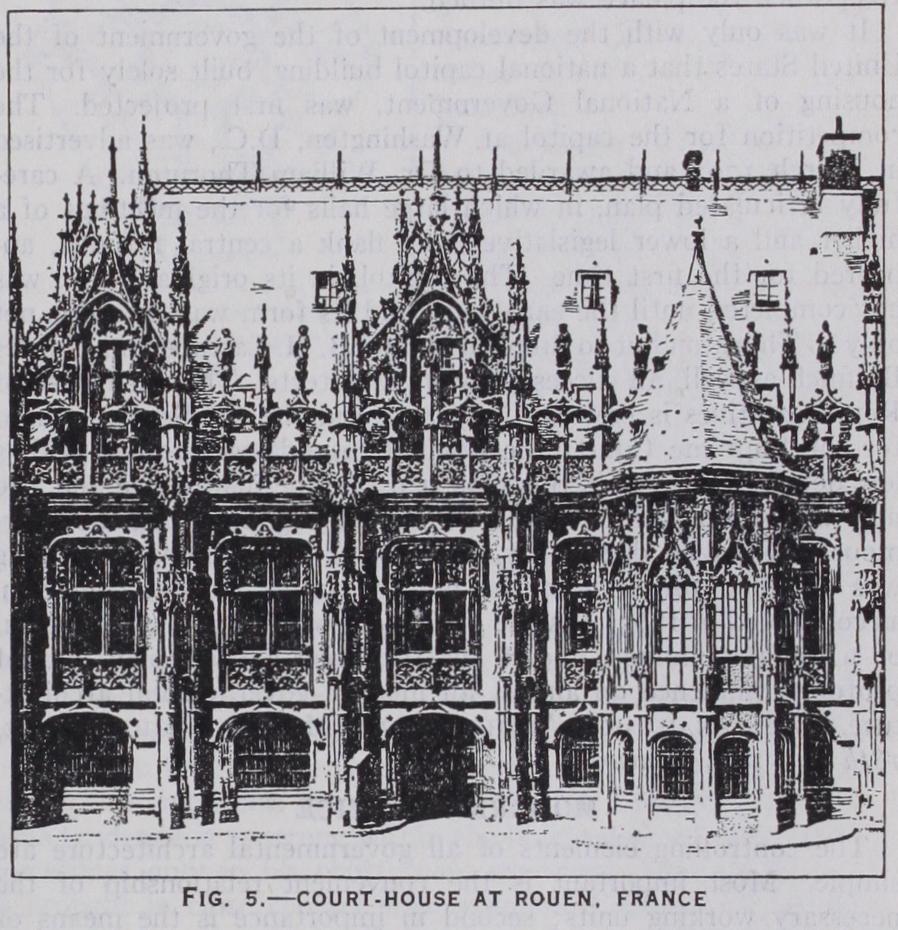

The second important type of governmental building that took form during the middle ages was the court-house or palais de justice. Most mediaeval examples are of the late Gothic period because only then had judicial processes become sufficiently divorced from royal, monastic or feudal domination to necessitate separate buildings. The earliest existing examples are the Maison de Pierre at Chartres and the Salle le Roi at Montdidier (both of the 14th century). By far the most famous is the lavish Palais de Justice at Rouen (begun before 1474, completed before 1509)• This magnificent building stands on three sides of a court and contains, not only the smaller court rooms, but two vast halls and a beautiful chapel. It is in this use of large halls that originated the tradition of having as an integral part of every court-house a great lobby where lawyers could confer with their clients.

No such development of national governmental buildings can be found during this period. Whatever national unity existed was centred in the residence of the sovereign, and when national councils or legislative bodies arose they were housed either in a royal palace or in religious buildings. To this day the French senate sits in the palace of the Luxembourg. In England, the king's council met wherever he happened to be, as at St. Albans, Oxford or Winchester, and the English parliament convened at the nearest convenient spot to the royal palace at Westminster, which was the chapter house of Westminster Abbey, until when it moved to St. Stephen's chapel within the palace itself. This remained the meeting place of the House of Commons until 1834 when the palace was burned.

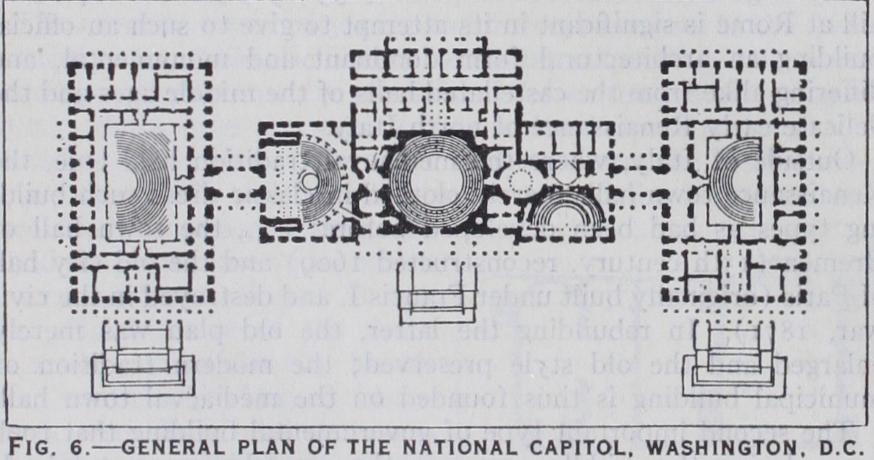

It was only with the development of the government of the United States that a national capitol building, built solely for the housing of a National Government, was first projected. The competition for the capitol at Washington, D.C., was advertised in March 1792 and awarded to Dr. William Thornton. A care fully articulated plan, in which large halls for the meetings of a higher and a lower legislative body flank a central rotunda, ap peared for the first time. The capitol, in its original form, was not completed until the early '3os, and its form was then due not only to Thornton but to Stephen Hallet, B. H. Latrobe and Charles Bulfinch as well, all successively its architects. The old House of Representatives is now Statuary hall, and the old Senate is used for the Supreme Court ; the original rotunda was roofed with a low dome. By the '5os this plan had become inadequate and two new wings were added by T. U. Walter, together with the enor mous colonnaded dome that now crowns the building; one wing was designed for each of the houses. In its present condition, as completed in 1865, it is one of the largest and most monumental of national buildings, and it has furnished a basic plan idea of profound influence on almost all modern governmental architec ture. (See RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE; MODERN ARCHITECTURE, i8th and igth Centuries.) The controlling elements of all governmental architecture are simple. Most important is the convenient relationship of the necessary working units ; second in importance is the means of communication between them, and from them to the outside. By virtue of its public and official function, a government building must have the means of communication highly developed and designed for convenience, directness and to give the most beautiful effect possible. As a result, there are many public spaces, such as lobbies, rotundas or salles des pas perdus, and the halls and corri dors are made as monumental as possible. Axial symmetry is an almost inevitable result, as the existence of an axis is not only expressive of direct communication, but also of direct view.

Owing to the complexity of modern government, governmental buildings can be divided into several classes, each of which must be treated separately. These classes are: (I) Municipal; (2) judicial; (3) legislative, either State, provincial or national; (4) administrative and executive.

Modern Municipal Buildings.

The requirements governing the design of a modern town hall are as follows: First, a hall or halls for the town council meetings; second, offices for the mayor or the councillors and their secretaries; third, offices for the finan cial and administrative sections of the town government, such as the tax board, building department, etc. In addition, particularly in European town halls, there are frequently great suites of State rooms for receptions and official banquets (cf. the ancient Greek prytaneum). In America, the typical smaller building frequently also contains an auditorium for popular meetings or entertain ments, and may also house the police department and the gaol. The most monumental example of the continental city hall is the great Paris Hotel de Ville, rebuilt, after the commune, by Ballu and Deperthes (1874-82). Fol lowing the original Francis I. style on the exterior, it was elaborated inside with all the decorative lav ishness then characteristic, and its great Salles des Fetes and mag nificent stairways, with decora tions by Puvis de Chavannes and others, form one of the most gor geous and effective official suites in the world. This precedent has affected French municipal build ing ever since. Characteristic ex amples of later mairies and hotels de ville that show a similar type of Renaissance classicism, lavish decoration and monumental plan are those of Neuilly-sur-Seine, by Dutocq and Simonet (1885) ; Versailles, by le Grand (1897) ; Tours, by Laloux (1896-1904) .In England, the dominance of the Gothic revival movement of the middle 19th century affected much municipal building. The town hall of Manchester, by Waterhouse (1868-7 7) , is the largest example of this, and its picturesque outline and original detail are typical of the best in Gothic revival work. The town hall of Hali fax, by Sir Charles Barry, completed by his son after his death in 186o, is a daring and unsuccessful attempt to treat a picturesque Victorian outline, essentially Gothic, in an elaborate Renaissance style. In more recent examples there is greater simplicity of composition and freedom of style. That of Sheffield, by Mount ford (1897), in a free early Renaissance style, is typical of the larger examples; that of Oxford, by Hare (1897), in modified Jacobean, is characteristic of the smaller.

Growing complexity of the administrative branches of city government has led inevitably to a type of building in which the council chamber and mayor's offices are subsidiary to the vast amount of office space required. This movement is best expressed in the London County Council Hall, won in competition in 1908 by Ralph Knott, but only completed in 1922. This vast building, in a severely classic, late English Renaissance style, forms an impressive decoration to the south bank of the Thames.

In Germany, the most interesting recent municipal buildings are those in which modernistic expression is consciously sought.

In that at Mulheim, by Pfeiler and Grosymann and the V erwal tungsgebaude at Berlin, by Lud wig Hoffman, the style is a mod ernistic neo-classic, freely tradi tional, and the effect one of re strained and harmonious monu mentality. The famous stadlialle at Hanover, by F. Scholer and Bonatz (1914), contains a vast circular hall, and the whole is treated in a much more bizarre and fantastic manner. .This is, however, more properly a municipal auditorium similar to a common American type, of which that at San Antonio, Texas, by Ayers, Willis and Jackson, is a good example. All three show the vitality of this movement in Ger many. A similar imaginative quality distinguishes the exquisitely restrained town hall at Joensuu, Finland, by Eliel Saarinen.

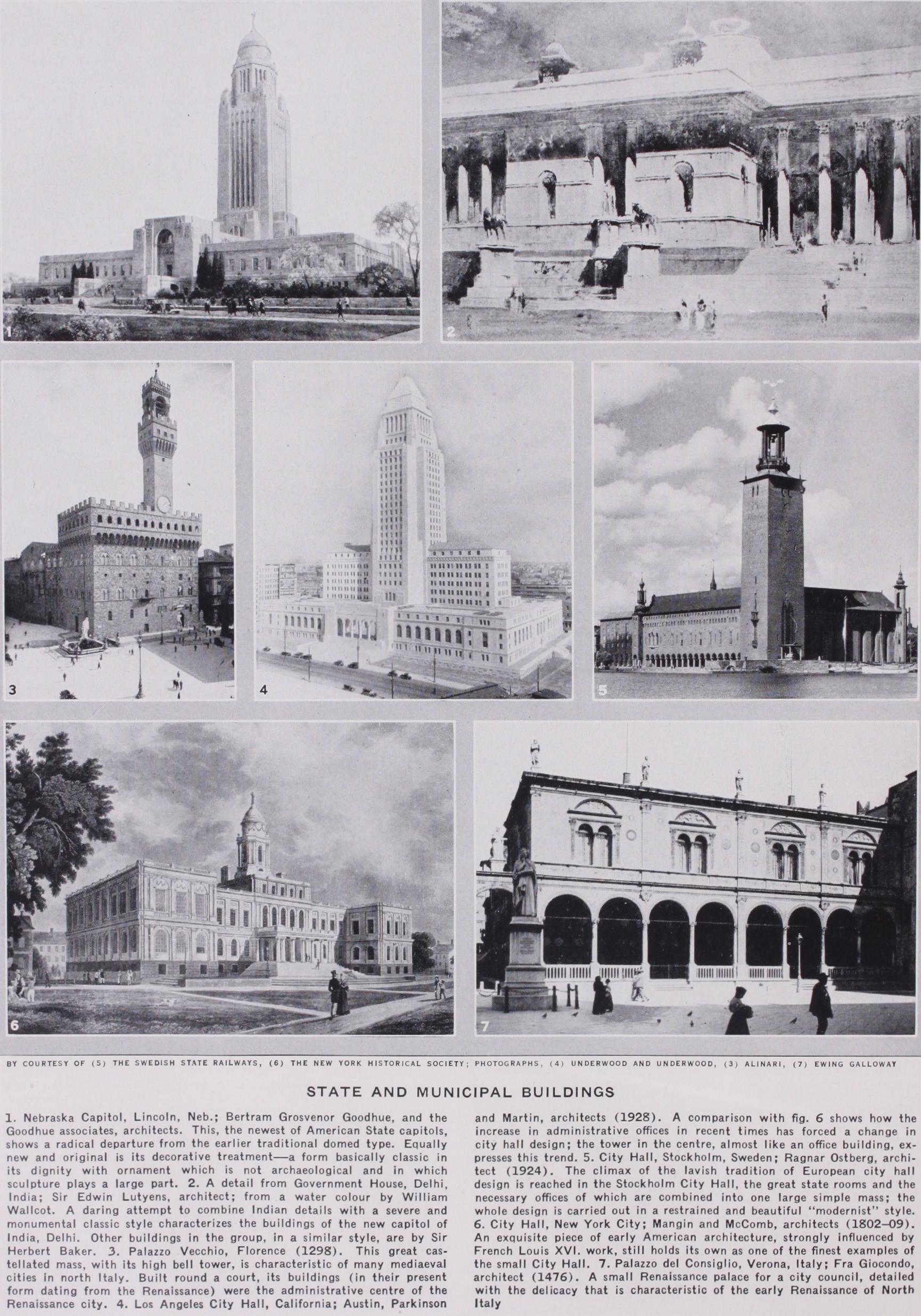

The most remarkable of the modernistic city halls is that at Stockholm, Sweden, by Ragnar Ostberg (completed 1924). This forms a dignified mass capped with a well designed tower and embodying in its base an arcade of great beauty. Inside, it is chiefly noteworthy for the brilliant colour decoration, especially the mosaics of the great official reception hall. (See MOSAIC.) American Town and City Halls.—Town and city halls in the United States can be divided into three classes. The first consists of the town halls of the small towns and villages, whose needs are simple and whose buildings, theref ore, are comparatively small. Faithfulness to the traditional style of the locality is general. In the East, colonial types predominate; in the far West, Spanish colonial; in the spaces between, there is more freedom.

The town hall of Weston, Mass., by Bigelow and Wadsworth, in a charming brick colonial, and the Plattsburg, N.Y., city hall, by John Russell Pope, in an austere Greek revival style, are charac teristic of these smaller halls. Other notable examples are those at Athol, Mass., by Brainerd, Leeds and Thayer, at Huntington, N.Y., by Peabody, Wilson and Brown and the village hall, Win netka, Ill., by Edwin Clark. The second type, that of the small city, is necessarily larger and more articulated, with greater office areas. This class owes much to the beautiful city hall of New York, then a small city, by Mangin and McComb (18o2 09), which Lafayette's secretary, A. Lavasseur, said was the only building worth looking at in New York (Lafayette en Arnerique, 1824, trans. 1829). This building is characterized by an unusual delicacy of detail that owes much to Louis XVI. inspiration. Its dome, rotunda and monumental staircase, council chamber, and the suite of offices and reception rooms over the entrance, are par ticularly noteworthy. Character istic modern examples are those of Portland, Me., by Carrere and Hastings, with a colonial flavour, and the group at Springfield, Mass., by Pell and Corbett, in which two colonnaded buildings flank a municipal clock tower.

The great city hall of San Francisco, California, by Bakewell and Brown, reaches the dimensions of an important State capitol.

It is, nevertheless, a compromise, lacking the intimacy of the small type, and due to its necessary small subdivisions, missing the simplicity of a great legislative building. To meet the same problem, New York was compelled to erect a great municipal office building to supplement its century old city hall. This, by McKim, Mead and White, is essentially a sky-scraper office building. Only the lavish classicism and dignity of its exterior distinguish it from its commercial neighbours. Thus far, the most successful Ameri can solution of the problem is the Los Angeles, Calif., city hall, by Austin, Parkinson and Martin, completed 1928. Here, for the first time, the two elements of town hall arid municipal office build ing are combined in the same structure and given adequate archi tectural expression.

Modern Judicial Buildings.

Just as the modern court sys tem has remained close to its traditional ancestry, so the modern court-house in its essential elements has changed little. Such a Renaissance court room as that in the Ayuntamiento of Valencia, which dates from 1535, could be used, even to its furniture, with out change, by almost any modern court. The salle des pas perdus, or monumental lobby, the court rooms and rooms for judges, lawyers, witnesses and archives, all appeared in court-houses of the 15th century, so that between such a building as the pic turesque Law Courts of London, by G. E. Street (completed 1882), and the Palais de Justice of Rouen, 400 years earlier, the difference is only one of detail. The Palais de Justice at Paris is typical of the 19th century continental court-house. It is of many dates, as it is on the site of and incorporates portions of a 13th century royal palace. Other portions were rebuilt after a fire in 1618, and its present form was completed by large rebuildings after the commune, and a new west front by J. L. Duc. Thus its plan represents a continual compromise between old and new.Nevertheless, two of the most remarkable modern public build ings of Europe are court-houses. The Palazzo di Giustizia at Rome, by Calderini (1889-191o), is a vast agglomeration of pseudo-classic detail, monumental and powerful in composition, but with too much meaningless small scale ornament which de tracts from the unmistakable vitality. A somewhat similar type of imagination characterizes the much more interesting Palais de Justice at Brussels, by Poelaert (1866-83) . Here everything is subservient to a vast and craggy grandeur.

American Court-houses.

It is in America that the court house has received a definitive form; as early as 1724 the germs of it are seen in the charming porticoed Court House at Ches ter, Va. The traditional elements have remained the same, and the classic tradition for governmental buildings, dating back to the be ginning of the 19th century, has almost completely dominated. The wide use of elevators, and the demand for economy in land usage, have produced a compact plan, generally in several storeys. The wide development of the jury system has also necessitated careful planning to give adequate jury rooms with the necessary services. The basic unit, therefore, consists of the court room proper, with its space for the public, witnesses, jury box, judge's bench and areas for counsel, clerks and stenographers and the press; the judge's office or chambers, and the jury room.

Since the time of the Gothic revival, classic treatment and an attempt to emphasize the dignity of the law are almost universal. This tendency is as strong within the building as without and it is sometimes only in his court room experience that an American is brought in close contact with a dignified and beautiful room, austere in form but lavish in fittings and decoration. The Shelby county court-house at Memphis, Tenn., by Hale and Rogers, with its dignified Ionic portico, and its pedimented end pavilions is characteristic of the classic grandeur obtained in many recent court-houses even in the smaller cities. The Hamilton county court-house at Cincinnati, O., shows the same tradition, applied to a much larger building. All of these modern trends in court-house design reached a conclusion in the court-house of New York county, at New York city, by Guy Lowell, completed in 1927, after his death. In this, a plan of striking originality, a central rotunda gives access to elevators surrounding it, which, in turn, communicate simply with the court rooms on each floor.

Modern Administrative Buildings.

Administrative build ings are of two broad classes, one consisting of those primarily for a public service, such as post offices and custom houses, and one of those devoted to purely administrative services, such as min istries. Owing to the gradual growth of public services of the first type their housing in many European countries has until recently been neglected ; they have frequently been forced into altered buildings, usually palaces, but in Rome and in Havana, Cuba, the post offices occupy former monastery buildings. Only in the largest cities are there exceptions, such as the rather undistin guished general post office of Paris (1884) by Guadet, or the great late Renaissance piles in London of the general post office proper (1910) and the general post office north (19o5), both by Henry Tanner. Recent years have seen greater attention paid to post office design, especially in Germany, but it is in the little Dutch city of Utrecht that the most beautiful of modern European post offices is to be found, designed by Crouwel.Custom houses similarly are seldom of architectural import in Europe. Almost the only one that has adequate dignity and con venience, is the great custom house in London. by David Lang (1817), partially rebuilt by Robert Smirke. Its vast length forms one of the most distinguished decorations of that portion of the Thames bank, and it is remarkable for its "Long Room" over 200 ft. long, where most of the business is transacted.

The lack of any adequate buildings into which these services could be placed in America was, from the beginning, a great in centive to the development of new types of building. As early as 1832 New York possessed a monumental custom house, designed by Town and Davis, in the Greek revival style, which is still (1928) standing at the corner of Nassau and Wall Sts. used for a passport office. The present New York custom house is a lavish building of Renaissance character, by Cass Gilbert. Of the smaller towns that at Wooster, O., by Wetmore, and New Haven, Conn., by J. G. Rogers, are typi cal; a notable combined Federal Court House and Post Office building is that at Denver, Colo., by Tracy, Swartwout and Litch field. The New York post office, by McKim, Mead and White, is interesting for its Corinthian colonnade.

Ministries and similar administrative buildings suffer from having a programme exactly like that of a modern office building; in general, the result is not distinguished. In European capitals, ministries are frequently housed in altered palaces, as in Paris and Vienna. In London, where they are concentrated along White hall and Parliament street they form a group, impressive in gen eral effect, but without individual distinction, except in the case of the Admiralty, by Ripley (1726), with an exquisite screen by Robert Adam (176o). The Renaissance group by Scott (1873), and Brydon (19oo-2o), containing many ministries is noteworthy.

In America, the classic tradition, under which the city of Wash ington, D.C., was started, has led to the imposing colonnade of the Treasury building, and within the loth century to the restrained Senate and House office buildings, by Carrere and Hastings.

Modern Buildings.

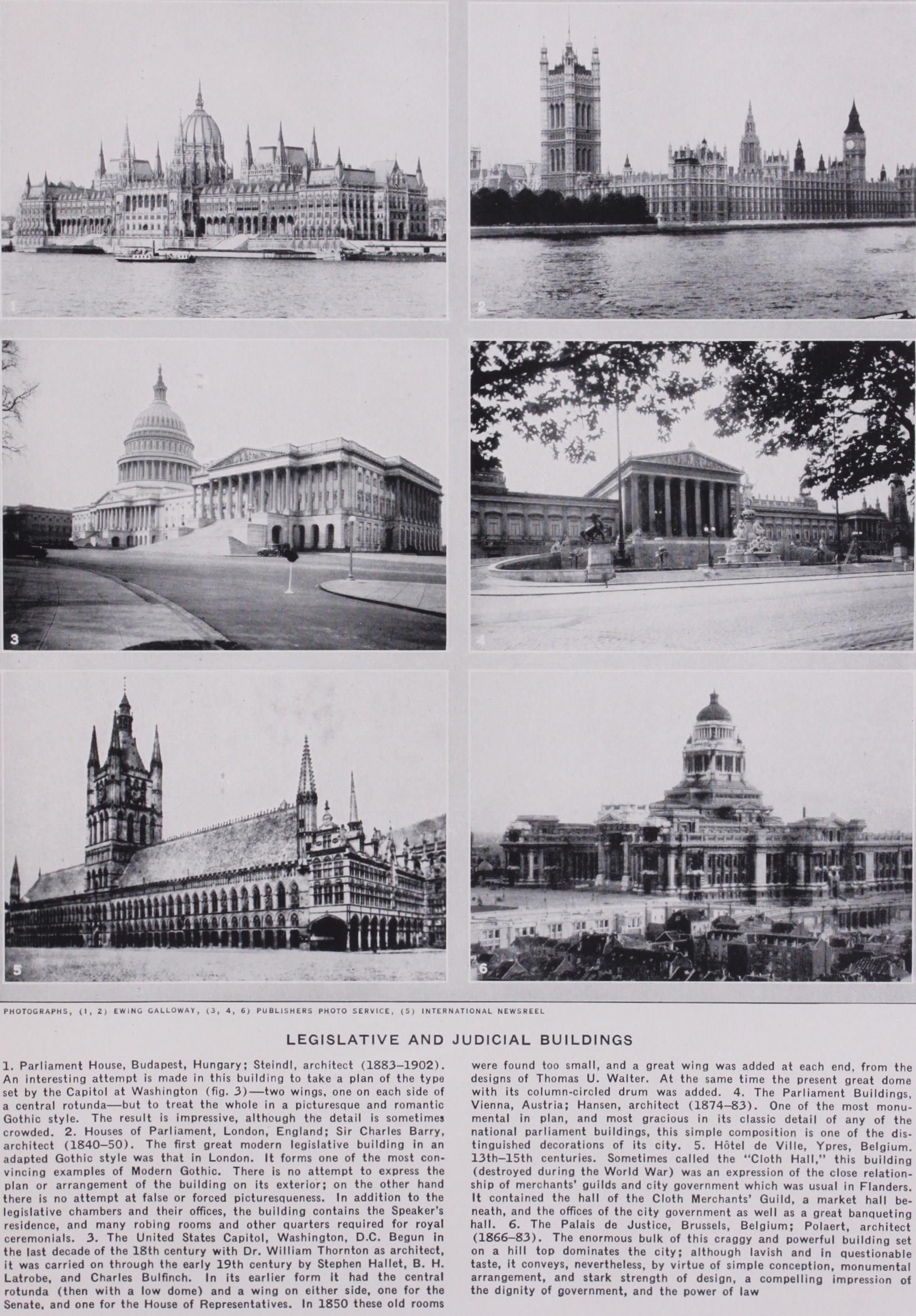

With the addition to the old Palais Bour bon (1722, by Girardini and Gabriel) of the great 12 columned pedimented front, in 1807, by Poyet, to express the dignity of the buildings used by the Chambre des Deputes, modern legislative architecture began. The classic tradition, there set, remained al most unbroken for 1 oo years all over the Western world ; to this precedent was added the influence of the U.S. Capitol at Washing ton, D.C., with its clear expression of two chambers, one on each side of a central public rotunda. The French Chambre des Deputes, reconstructed (1822-33) by de Joly, and the Senate, in the Luxembourg palace (1836-41), by de Gisors, are characteristic lavish developments of a classic amphitheatre plan already adopted in the Washington Capitol. The simplicity and directness of the U.S. Capitol plan have inspired many modern legislative buildings of two chambers. It is almost universal in American State capi tols, from such early examples as the Massachusetts State house at Boston, completed 1798, by Charles Bulfinch. To such loth century examples as that at Jefferson City, Mo., by Tracy, Swartwout and Litchfield, that of Minnesota, at St. Paul, by Cass Gilbert, the Wisconsin capitol at Madison, by George B. Post and Sons, and the Territorial Capitol of Porto Rico at San Juan, by Carmaega and Nichols. In Hungary, the same type ap pears in the parliament building at Budapest, by Steindl (1883 1902 ), although the style is flamboyant Gothic. In Vienna, the parliament building by Hansen (1874-83), has a similar plan.

In the Wisconsin capitol the architects were forced to have four wings, forming a cross, instead of the usual two. This was at best a compromise. Finally, in the masterly Nebraska State capitol, at Lincoln, the late Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue accepted the prob lem and solved it. In place of the usual two-winged building with a dome, there is a vast rectangle, divided by a cross into four courts. One arm of the cross contains the monumental corridor, with a central rotunda. The cross arm holds the two legislative houses. Above the ro tunda rises a tower of many storeys, and the administrative offices ring the courts and occupy the tower as well.

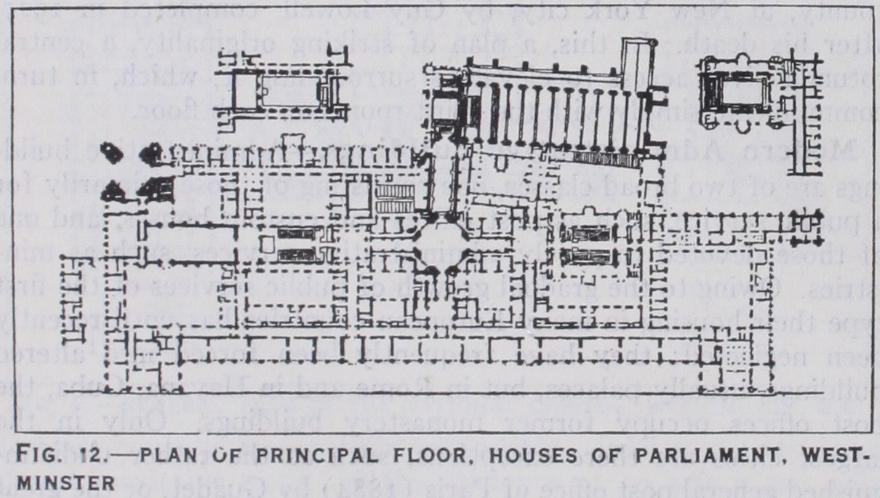

The Houses of Parliament in London, by Sir Charles Barry (1840-5o) is an interesting and remarkable exception to the gen eral rule in both plan and style.

Here, the House of Lords and the House of Commons are but in cidents in a vast composition in which are placed the members' offices, dining-rooms and libraries, the speaker's residence and all the rooms required for the traditional and picturesque ritual. In style, the whole is treated in lavish Perpendicular Gothic, and the exterior aim has been to achieve picturesque massing, with the Victoria tower at one end and the clock tower at the other, rather than any expression of interior function.

The foundation of new provincial capitals, in Australia, 1911, and in India, 1919, furnished a new opportunity for the adequate housing of complete dominion governments. In Australia, the competition for the lay-out of the city of Canberra was won by Walter Griffin of Chicago, with a most comprehensive plan. The first of the buildings, in connection with this, was formally opened in the summer of 1928. The eventual scheme consists of a rec tangular plaza with the departmental administrative buildings flanking it on each side, and at its head, a great structure con taining the parliament and a library. Behind is a circular plaza flanked by the residences of the premier and the governor-general.

In Delhi, a much more lavish scheme is under construction. It consists of an enormous avenue, or plaza, flanked by two groups of administrative offices known as the secretariat buildings, by Sir Herbert Baker, and headed by the picturesque mass of the Gov ernment house, the official residence of the viceroy, by Sir Edward Lutyens. At one side is the legislative building, by Baker, an enormous circle, with three interior courts, between which are the three houses, the council of princes, the assembly, and the council of State, with a circular library joining them in the centre. Lower down on the main axis is a great memorial arch, by Lut yens; smaller buildings are to flank the avenue, one of them, the record office, by Lutyens, being now (1928) under construction. All the buildings of this tremendous group are designed with great lavishness of plan and interior arrangement, and exteriors in which classic Renaissance and Indian detail are daringly combined and powerfully massed.

An even greater opportunity is offered in the proposed group of buildings for the League of Nations at Geneva. The opening created by the site on the shore of the lake, and by the programme, is one to stimulate the best efforts of modern architects.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J.

Bartram, Observations on his Travels in 1743 Bibliography.-J. Bartram, Observations on his Travels in 1743 (1751) ; Gourlier, Biet, Grillon and Tardieu, Choix d'edifices public, etc. (1825-5o) ; A. Levasseur, Lafayette en Amerique, 1824-25 (1829) ; J. Coney, Engravings of Ancient Cathedrals, Hotels de Ville, etc. (1832) ; F. Narjoux, Monuments eleves Par la ville (1880-83) ; L. H. Morgan, Houses and House Life of the American Aborigines (i881) ; Handbuch der Architektur, iv., 7 (1887) ; R. Lanciani, Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Excavations (1889) ; P. Planat, Encyclopedic de l'architecture (189o) ; Adler, Borr, Dorpfeld, Graeber and Graef, Die Baudenkmaler von Olympia (1892) ; E. A. Gardner, "Excavations at Megalopolis," in special no. Jour. of Hellenic Studies (1892) ; F. Cornish, Concise Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1898) ; R. Lanciani, New Tales of Old Rome (19o1) ; Wiegand and Schrader, Ergebnisse der Ausgraben and Unterschungen (Priene) (1904) ; C. Enlart, Manuel d'archeologie f rancaise, ii. (19o4) ; O. Stiehl, Rathaus im Mittelalter (19o5) ; F. R. Hiorns, "Modern Town Halls," in R.I.B.A. Journal, xiv. (1906-.o7) ; A. Grisebach, Das deutsche Rathaus der Renaissance (1907) ; A. Marquand, Greek Architecture (1909) ; H. E. Warren, "Mediaeval Town Halls of Italy," in Arch. Quart., Harvard Univ. (March, 1912) ; V. Lamperez y Romea, Arqui tectura Civil Espanola (1922) ; L. H. Morgan, League of the . . . Iroquois (1851; n. ed., 192 2) ; Cremers, Fahrenkamps and W. Hendel, two articles on "Miilheim Stadhalle," in Deutsche Kunst and Dekora tion, lviii. (May 1926) . For Delhi, see Arch. Rev. vol. 6o (Dec. 1926) and R.I.B.A. Jour., vol. 35 (1927). (T. F. H.)