The General Principles of Greek Art

THE GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GREEK ART The study of Greek art is one which is eminently progressive. It has over the study of Greek literature the immense advantage that its materials increase far more rapidly. And it may well be maintained that a sound and methodic study of Greek art is as indispensable as a foundation for an artistic and archaeological education as the study of Greek poets and orators is as a basis of literary education. The extreme simplicity and thorough ration ality of Greek art make it an unrivalled field for the training and exercise of the faculties which go to the making of the art critic and art historian.

Before proceeding to sketch the history of its rise and decline, it is desirable briefly to set forth the principles which underlie it (see also P. Gardner's Principles of Greek Art).

As the literature of Greece is composed in a particular language, the grammar and syntax of which have to be studied before the works in poetry and prose can be read, so Greek works of art are composed in what may be called an artistic language. To the accidence of a grammar may be compared the mere technique of sculpture and painting ; to the syntax of a grammar correspond the principles of composition and grouping of individual figures into a relief or picture. By means of the rules of this grammar the Greek artist threw into form the ideas which belonged to him as a personal or a racial possession.

No nation is in its works wholly free from the domination of climate and geographical position; least of all a people so keenly alive to the influence of the outer world as the Greeks. They lived in a land where the soil was dry and rocky, far less hospit able to vegetation than that of western Europe, while the land horizon was on all sides bounded by hard and jagged lines of mountain. The sky was extremely clear and bright, sunshine for a great part of the year almost perpetual, and storms, which are more than passing gales, rare. It was in accordance with these natural features that temples and other buildings should be simple in form and bounded by clear lines. Such forms as the cube, the oblong, the cylinder, the triangle, the pyramid abound in their constructions. Just as in Switzerland the gables of the chalets match the pine-clad slopes and lofty summits of the mountains, so in Greece, amid barer hills of less elevation, the Greek temple looks thoroughly in place. But its construction is related not only to the surface of the land, but also to the character of the race. Emile Boutmy, in his interesting Pllilosophie de l'architecture en Greee, has shown how the temple is a triumph of the senses and the intellect, not primarily emotional, but showing in every part definite purpose and design. It also exhibits in a remarkable degree the love of balance, of symmetry, of a mathematical proportion of parts and correctness of curvature which belong to the Greek artist.

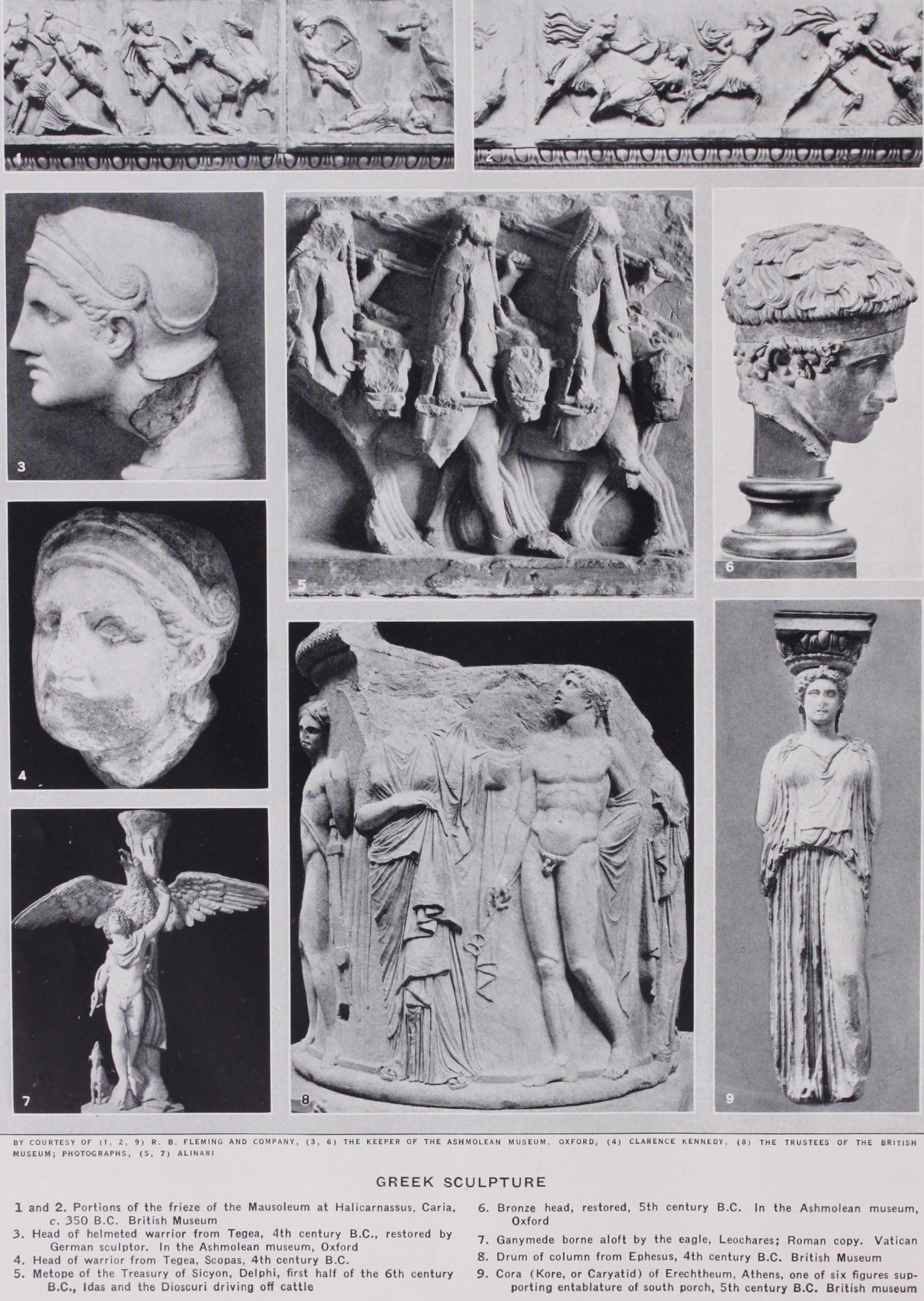

Here, however, our concern is not with the purposes or arrange ments of a temple, but with its sculptural decoration, and we would note that elaborate decoration is reserved for those parts of the temple which have, or at least appear to have, no strain laid upon them. It is true that in the archaic age experiments were made in carving reliefs on the lower drums of columns (as at Ephesus) and on the line of the architrave (as at Assus). But such examples were not followed. Nearly always the spaces re served for mythological reliefs or groups are the tops of walls, the spaces between the triglyphs, and particularly the pediments surmounting the two fronts, which might be left hollow without danger to the stability of the edifice. Detached figures in the round are in fact found only in the pediments, or standing upon the tops of the pediments. And metopes are sculptured in higher relief than friezes.

"When we examine in detail even the simplest architectural decoration, we discover a combination of care, sense of propor tion, and reason. The flutings of an Ionic column are not in sec tion mere arcs of a circle, but made up of a combination of curves which produce a beautiful optical effect ; the lines of decoration, as may be best seen in the case of the Erechtheum, are cut with a marvellous delicacy. Instead of trying to invent new schemes, the mason contents himself with improving the regular patterns until they approach perfection, and he takes everything into con sideration. Mouldings on the outside of a temple, in the full light of the sun, are differently planned from those in the diffused light of the interior. Mouldings executed in soft stone are less fine than those in marble. The mason thinks before he works and while he works, and thinks in entire correspondence with his sur roundings." (Principles of Greek Art, P. 44.) Greek architecture, however, is treated under ARCHITECTURE; we will therefore proceed to speak briefly of the principles ex emplified in sculpture. Existing works of Greek sculpture fall easily into two classes. The first comprises what may be called works of substantive art, statues or groups made for their own sake and to be judged by themselves. Such are cult-statues of deities from temple and shrine, honorary portraits of rulers or of athletes, dedicated groups and the like. The second comprises decorative sculptures, such as were made, usually in relief, for the decoration of temples and tombs and other buildings, and were intended to be subordinate to architectural effect.

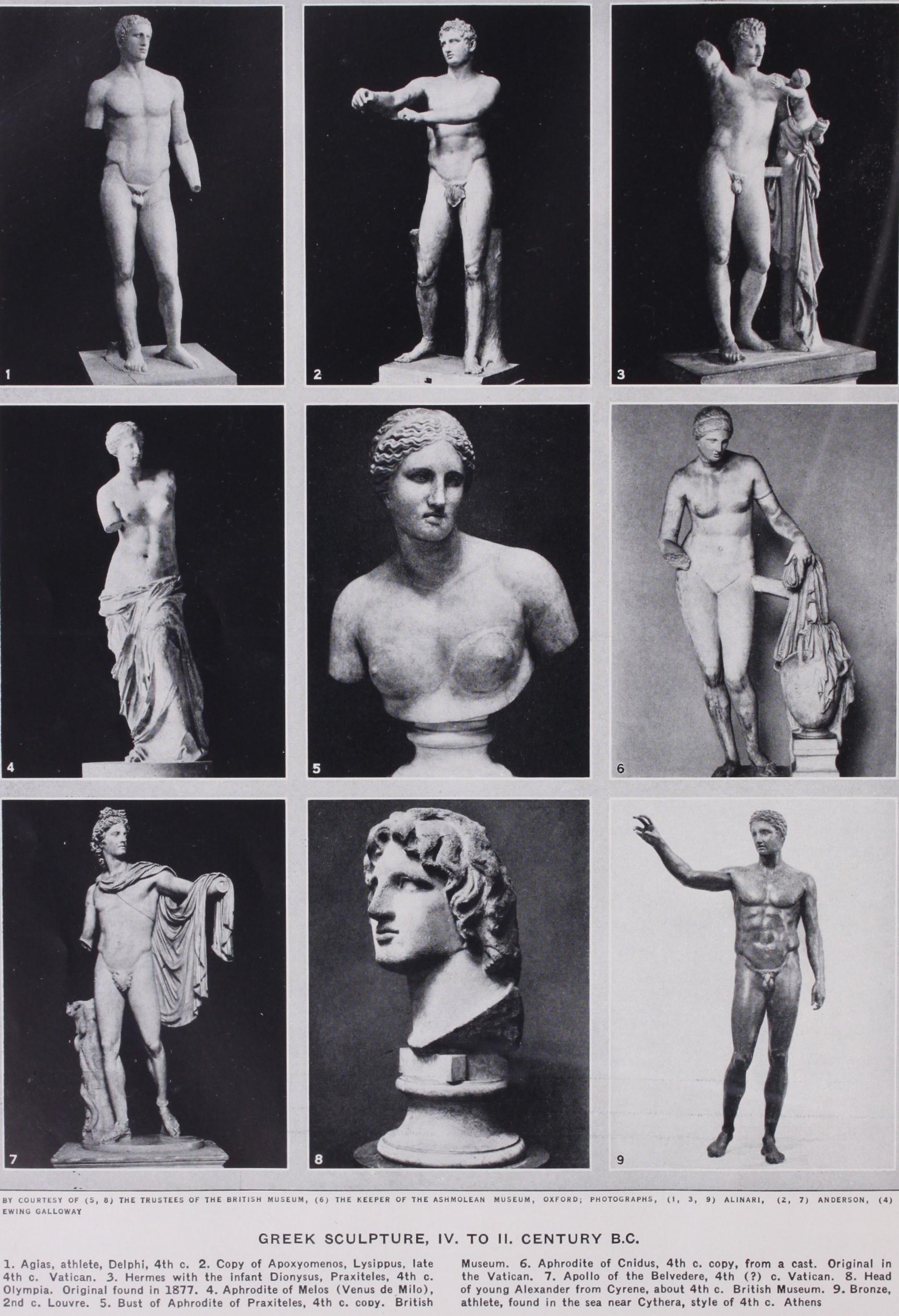

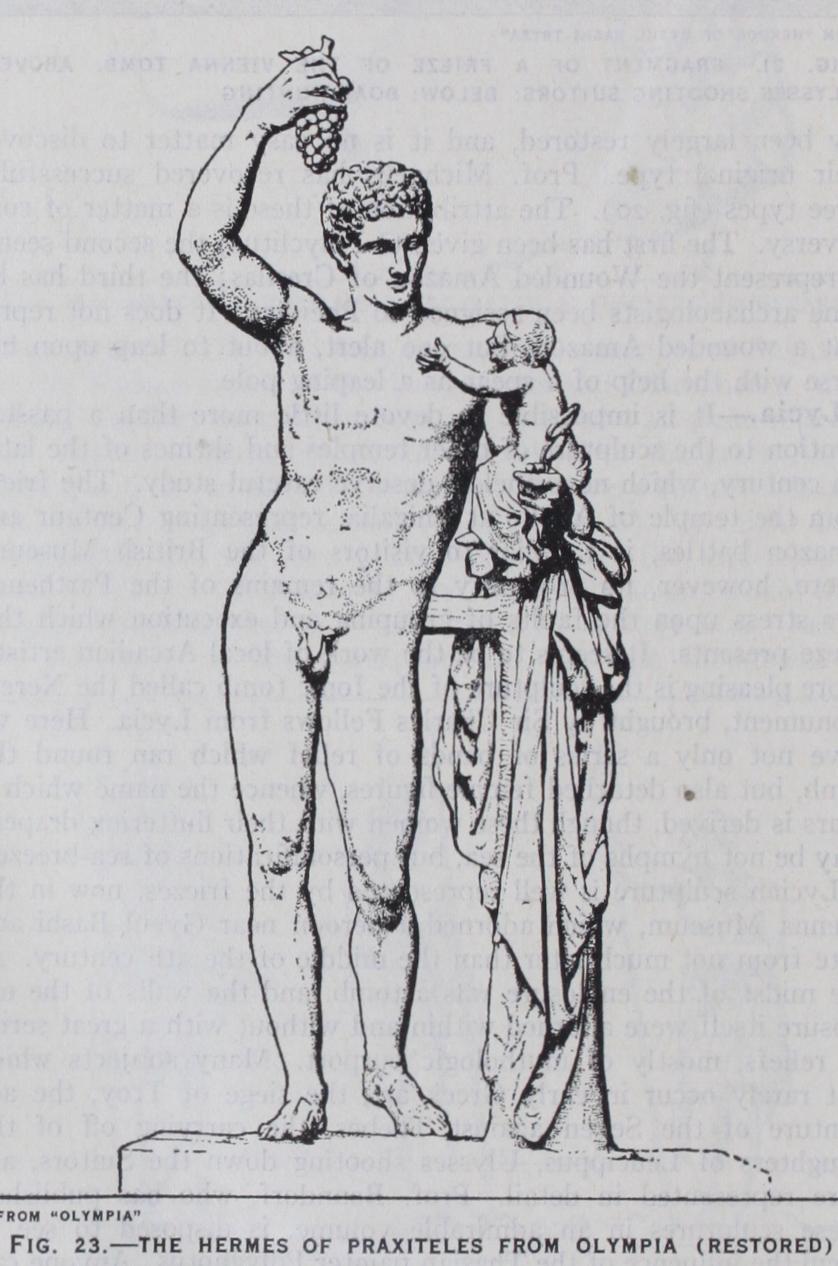

Speaking broadly, it may be said that the works of substantive sculpture in our museums are in the great majority of cases copies of doubtful exactness and very various merit. The Hermes of Praxiteles (P1. VI., fig. 3) is almost the only marble statue which can be assigned positively to one of the great sculptors; we have to work back towards the productions of the peers of Praxiteles through works of poor execution, often so much restored in modern times as to be scarcely recognizable. Decorative works, on the other hand, are very commonly originals, and their date can often be accurately fixed, as they belong to known buildings. They are thus infinitely more trustworthy and more easy to deal with than the copies of statues of which the museums of Europe, and more especially those of Italy, are full. They are also more commonly unrestored. But yet there are certain disadvantages attaching to them. Decorative works, even when carried out under the supervision of a great sculptor, were but seldom ex ecuted by him. Usually they were the productions of his pupils or masons. Thus they are not on the same level of art as substan tive sculpture. And they vary in merit to an extraordinary extent, according to the capacity of the man who happened to have them in hand, and who was probably but little controlled. Every one knows how noble are the pedimental sculptures of the Parthenon. But there is no reason why they should be so vastly superior to the frieze from Phigalia ; nor why the heads from the temple at Tegea should be so fine, while those from the contemporary temple at Epidaurus should be comparatively insignificant. From the records of payments made to the sculptors who worked on the Erechtheum at Athens it appears that they were ordinary masons, some of them not even citizens, and paid at the rate of 6o drachms (about 6o francs) for each figure, whether of man or horse, which they produced. Such piece-work would not, in our days, produce a very satisfactory result.

I. Works of substantive sculpture may be divided into two classes, the statues of human beings and those of the gods. The line between the two is not, however, very easy to draw, or very definite. For in representing men the Greek sculptor had an irresistible inclination to idealize, to represent what was generic and typical rather than what was individual, and the essential rather than the accidental. And in representing deities he so fully anthropomorphized them that they became men and women, only raised above the level of everyday life and endowed with a super human stateliness. Moreover, there was a class of heroes repre sented largely in art who covered the transition from men to gods. For example, if one regards Heracles as a deity and Achilles as a man of the heroic age and of heroic mould, the line between the two will be found to be very narrow.

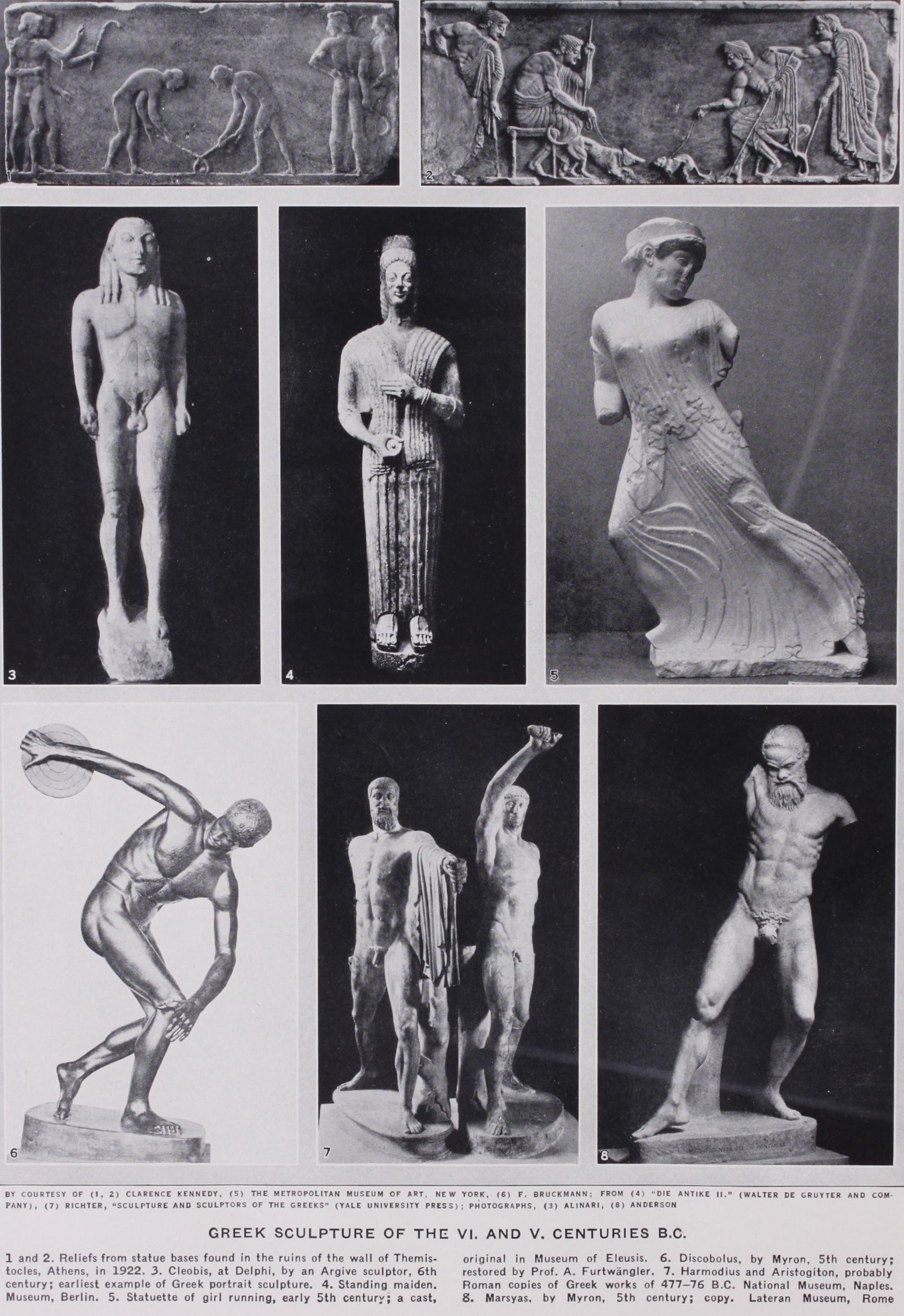

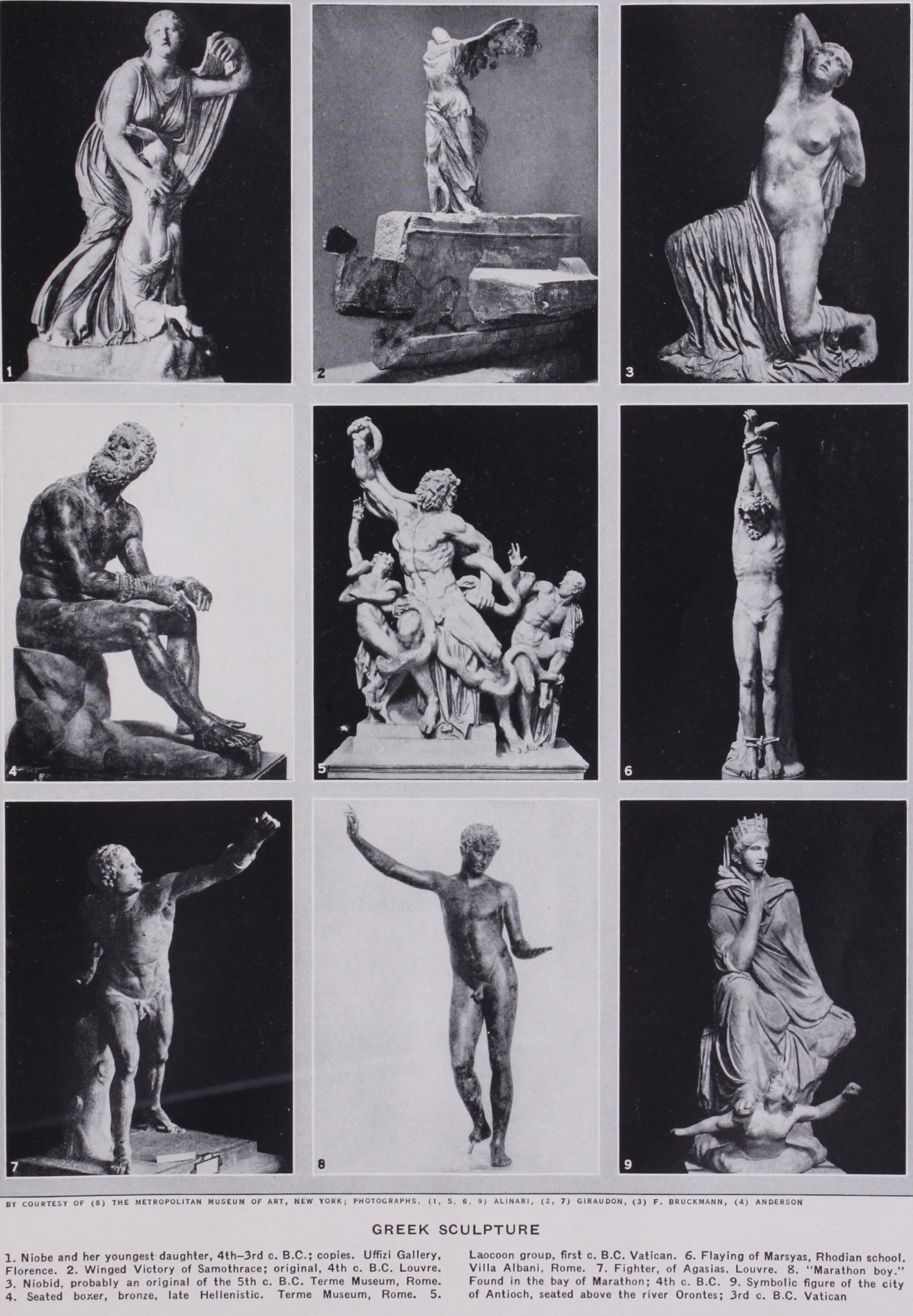

Nevertheless one may for convenience speak first of human and afterwards of divine figures. It was the custom from the 6th century onwards to honour those who had done any great achievement by setting up their statues in conspicuous positions. The earliest example we have is the portraits of the twins Cleobis and Biton from Delphi mentioned by Herodotus (Pl. II., fig. 3) . Another of the earliest examples is that of the tyrannicides, Harmodius and Aristogiton, a group, a copy of which has come down to us (Pl. II., fig. 7). Again, people who had not won any distinction were in the habit of dedicating to the deities portraits of themselves or of a priest or priestess, thus bringing themselves, as it were, constantly under the notice of a divine patron. The rows of statues before the temples at Miletus, Athens and else where came thus into being. But from the point of view of art, by far the most important class of portraits consisted of athletes who had won victories at some of the great games of Greece, at Olympia, Delphi or elsewhere. Early in the 6th century the cus tom arose of setting up portraits of athletic victors in the great sacred places. We have records of numberless such statues exe cuted by all the greatest sculptors. When Pausanias visited Greece he found them everywhere far too numerous for complete mention.

It is the custom of studying and copying the forms of the finest of the young athletes, combined with the Greek habit of complete nudity during the sports, which lies at the basis of Greek excellence in sculpture. Every sculptor had unlimited op portunities for observing young vigorous bodies in every pose and in every variety of strain. The natural sense of beauty which was an endowment of the Greek race impelled him to copy and pre serve what was excellent, and to omit what was ungainly or poor. Thus there existed, and in fact there was constantly accumulating, a vast series of types of male beauty, and the public taste was cultivated to an extreme delicacy. And of course this taste, though it took its start from athletic customs, and was mainly nurtured by them, spread to all branches of portraiture, so that elderly men, women, and at last even children, were represented in art with a mixture of ideality and fidelity to nature such as has seldom been reached by the sculpture of any other people.

The statues of the gods began with stiff and ungainly figures cut out of the trunk of a tree. In the Greece of late times there were still standing rude pillars, with the tops sometimes cut into a rough likeness to the human form. And in early decoration of vases and vessels one may find Greek deities represented with wings, carrying in their hands lions or griffins, bearing on their heads lofty crowns. But as Greek art progressed it grew out of this crude symbolism. In the language of Brunn, the Greek artists borrowed from Oriental or Mycenaean sources the letters used in their works, but with these letters they spelled out the ideas of their own nation. What the artists of Babylon and Egypt express in the character of the gods by added attribute or symbol, swift ness by wings, control of storms by the thunderbolt, traits of character by animal heads, the artists of Greece work more and more fully into the sculptural type ; modifying the human subject by the constant addition of something which is above the ordinary level of humanity, until we reach the Zeus of Pheidias or the Demeter of Cnidus. When the decay of the high ethical art of Greece sets in, the gods become more and more warped to the merely human level. They lose their dignity, but they never lose their charm.

2. The decorative sculpture of Greece consists not of single figures, but of groups; and in the arrangement of these groups the strict Greek laws of symmetry, of rhythm, and of balance, come in. We will take the three most usual forms, the pediment, the metope and the frieze, all of which belong properly to the temple, but are characteristic of all decoration, whether of tomb, trophy or other monument.

The form of the pediment is triangular; the height of the tri angle in proportion to its length being about i :8. The conditions of space are here strict and dominant; to comply with them re quires some ingenuity. To a modern sculptor the problem thus presented is almost insoluble; but it was allowable in ancient art to represent figures in a single composition as of various sizes, in correspondence not to actual physical measurement but to import ance. As the more important figures naturally occupy the midmost place in a pediment, their greater size comes in conveniently. And by placing some of the persons of the group in a standing, some in a seated, some in a reclining position, it can be so con trived that their heads are equidistant from the upper line of the pediment.

The statues in a Greek pediment, which are after quite an early period usually executed in the round, fall into three, five or seven groups, according to the size of the whole. As examples to illus trate this exposition we take the two pediments of the temple at Olympia, the most complete which have come down to us, which are represented in figs. 13 and r4.

The metopes were the long series of square spaces which ran along the outer walls of temples between the upright triglyphs and the cornice. Originally they may have been left open and served as windows; but the custom came in as early as the 7th century, first of filling them in with painted boards or slabs of stone, and next of adorning them with sculpture. The metopes of the Treas ury of Sicyon at Delphi (P1. IV., fig. 5) are as early as the first half of the 6th century. This recurrence of a long series of square fields for occupation well suited the genius and the habits of the sculptor. As subjects he took the successive exploits of some hero such as Heracles or Theseus, or the contemporary groups of a battle. His number of figures was limited to two or three, and these figures had to be worked into a group or scheme, the main features of which were determined by artistic tradition, but which could be varied in a hundred ways so as to produce a pleasing and in some degree novel result.

With metopes, as regards shape, may be compared the reliefs of Greek tombs, which also usually occupy a space roughly square, and which also comprise but a few figures arranged in a scheme generally traditional. A figure standing, giving his hand to one seated, two men standing hand in hand, or a single figure in some vigorous pose, is sufficient to satisfy the simple and severe taste of the Greeks.

In regard to friezes, which are long reliefs containing figures ranged between parallel lines, there is more variety of custom. In temples the height of the relief from the background varies ac cording to the light in which it was to stand, whether direct or diffused. Almost all Greek friezes, however, are of great simplic ity in arrangement and perspective. Locality is at most hinted at by a few stones or trees, never actually portrayed. There is sel dom more than one line of figures, in combat or procession, their heads all equidistant from the top line of the frieze. They are often broken up into groups ; and when this is the case, figure will often balance figure on either side of a central point almost as rigidly as in a pediment. An example of this will be found in the sections of the Mausoleum frieze shown in Plate IV., figs. i and 2. Some of the friezes executed by Greek artists for semi-Greek peo ples, such as those adorning the tomb at Trysa in Lycia, have two planes, the figures in the background being at a higher level.

The rules of balance and symmetry in composition which are followed in Greek decorative art are still more clearly to be dis cerned in the paintings of vases, which must serve, in the absence of more dignified compositions, to enlighten us as to the methods of Greek painters. Great painters would not, of course; be bound by architectonic rule in the same degree as the mere workmen. But in any case the fact must never be lost sight of that Greek painting of the earlier ages was of extreme simplicity. It did not represent localities, save by some slight hint ; it had next to no perspective; the colours used were but very few even down to the days of Apelles. Most of the great pictures of which we hear consisted of but one or two figures; and when several figures were introduced they were kept apart and separately treated, though, of course, not without relation to one another. Idealism and ethical purpose must have predominated in painting as in sculpture and in the drama and in the writing of history. The laws of balance and symmetry in Greek drawing are perhaps best shown in the decora tion of vases (see POTTERY).

To begin with, there was a rise of national art, after the de struction of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations of early Greece by the irruption of tribes from the north (see ARCHAEOL OGY), and then the Roman age of Greece, after which the Greek art works in the service of the conquerors (see ROMAN ART). The period (roughly 800–?5o B.C.) is divided into four sections : (I) to the Persian Wars, 48o B.C. ; (2) the period of the early schools of art, 480-400 B.C. ; (3) that of the later great schools, 400 300 B.C.; (4) that of Hellenistic art, 300-50 B.C. In dealing with these successive periods this article is confined to sculpture and painting, which in Greece are closely connected. The arts—pot tery, gem-engraving, coin-stamping and the like—are treated under their separate headings, and the reader is also referred to the biographical accounts of the chief artists (PHEIDIAS, PRAxI The Aegean or Mycenaean civilization was for the most part destroyed by what appears to have been a gradual invasion from the north; its racial character is much in dispute, though archaeo logical evidence abundantly proves that it was the conquest of a more by a less rich and civilized race. In the graves of the period (9oo-600 B.c.) is found none of the wealthy spoil which has made celebrated the tombs of Mycenae and Vaphio (q.v.). The character of the pottery and the bronze-work which is found in these later graves reminds one of the funerary art of Hallstatt and other sites belonging to what is called the bronze age of North Europe. Its predominant characteristic is the use of geometrical forms, the lozenge, the triangle, the maeander, the circle with tan gents, in place of the elaborate spirals and plant-forms which mark Mycenaean ware. For this reason the period from the 9th to the 7th century in Greece passes by the name of "the Geometric Age." It is commonly held that in the remains of the geometric age is traced the influence of the Dorians, who, coming in as a hardy but uncultivated race, probably of purer Aryan blood than the previous inhabitants of Greece, not only brought to an end the wealth and the luxury which marked the Mycenaean age, but also replaced an art which was in character essentially southern by one which belonged rather to the north and the west. The great difficulty inherent in this view, a difficulty which has yet to be met, lies in the fact that some of the most abundant and char acteristic remains of the geometric age which we possess come, not from Peloponnesus, but from Athens and Boeotia, which were never conquered by the Dorians. For the early history of Greek work in gold and bronze we must refer to the articles BRONZE and GOLDSMITHS' AND SILVERSMITHS' WORK.

Architecture and Sculpture.

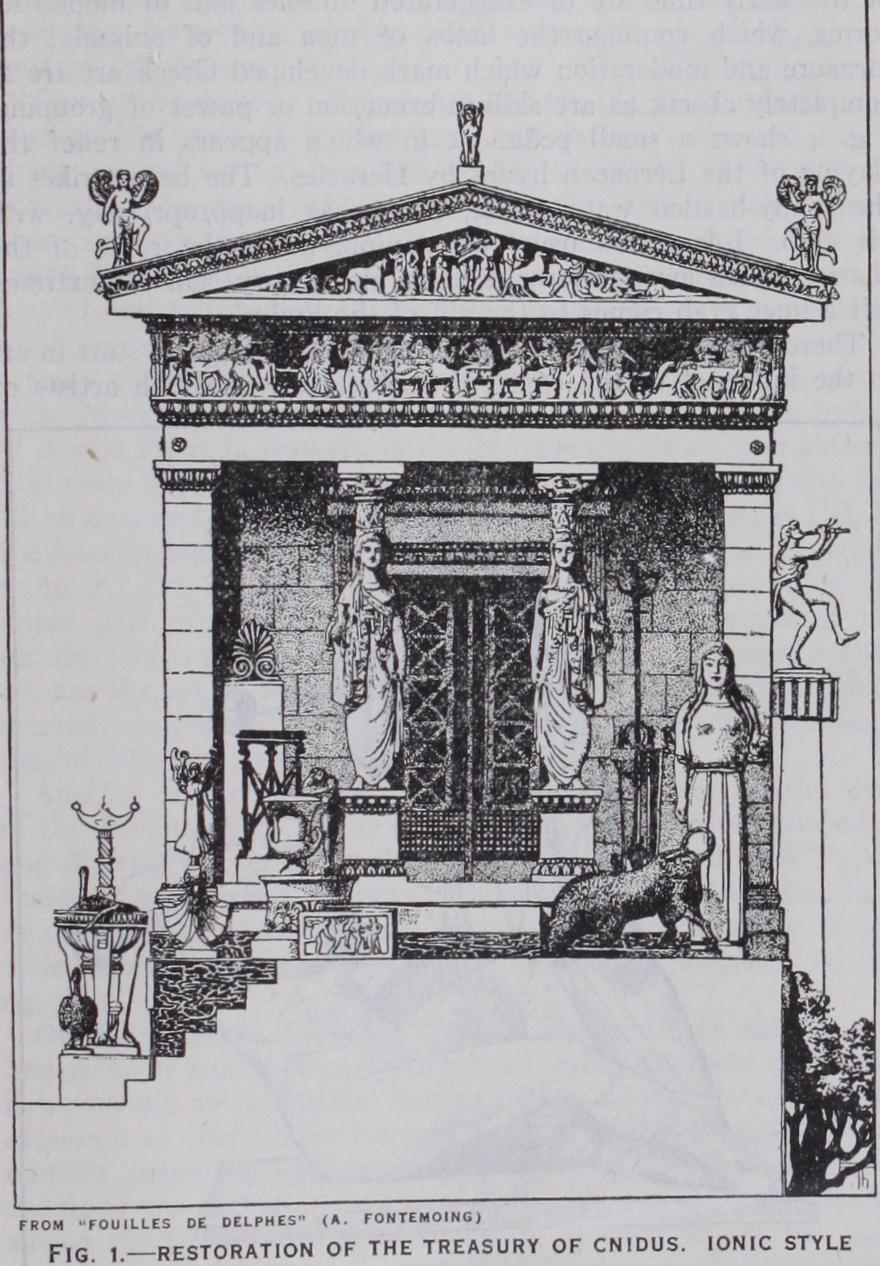

The Greek temple in its char acter and form gives the clue to the whole character of Greek art. It is the abode of the deity, who is represented by his sacred image ; and the flat surfaces of the temple offer a great field to the sculptor for the depicting of sacred legend. The process of dis covery has emphasized the line which divides Ionian from Dorian architecture and art. The Ionians were a people more susceptible than were the Dorians to oriental influences. The dress, the art, the luxury of western Asia attracted them with irresistible force. We may suspect, as Brunn has suggested, that Ionian artists worked in the great Assyrian and Persian palaces (and that the wall reliefs of those palaces were in part their handiwork. Some of the great temples of Ionia have been excavated in recent times, notably those of Apollo at Miletus, of Hera at Samos, and of Artemis at Ephesus. Very little, however, of the architecture of the 6th century temples of those sites has been recovered, though the French, who have been excavating at Delphi more or less con tinuously since 1892, have successfully restored the treasury of the people of Cnidus (fig. I), which is quite a gem of Ionic style, the entablature is supported in front not by pillars but by two maidens or Corae, and a frieze runs all round the building above. But though this building is of Ionic type, it is scarcely in the technical sense of Ionic style, since the columns have not Ionic capitals, but are carved with curious reliefs. The Ionic capital proper is developed in Asia by degrees (see ARCHITECTURE, ORDER and CAPITAL; also Perrot and Chipiez, Hist. de fart, vii. ch. 4).The Doric temple is not wholly of European origin, yet it was developed mainly in Hellas and the west. The most ancient ex ample is the Heraeum at Olympia, next to which come the frag mentary temples of Corinth and of Selinus in Sicily. With the early Doric temple we are familiar from examples which have survived in fair preservation to our own days at Agrigentum in Sicily, Paestum in Italy, and other sites.

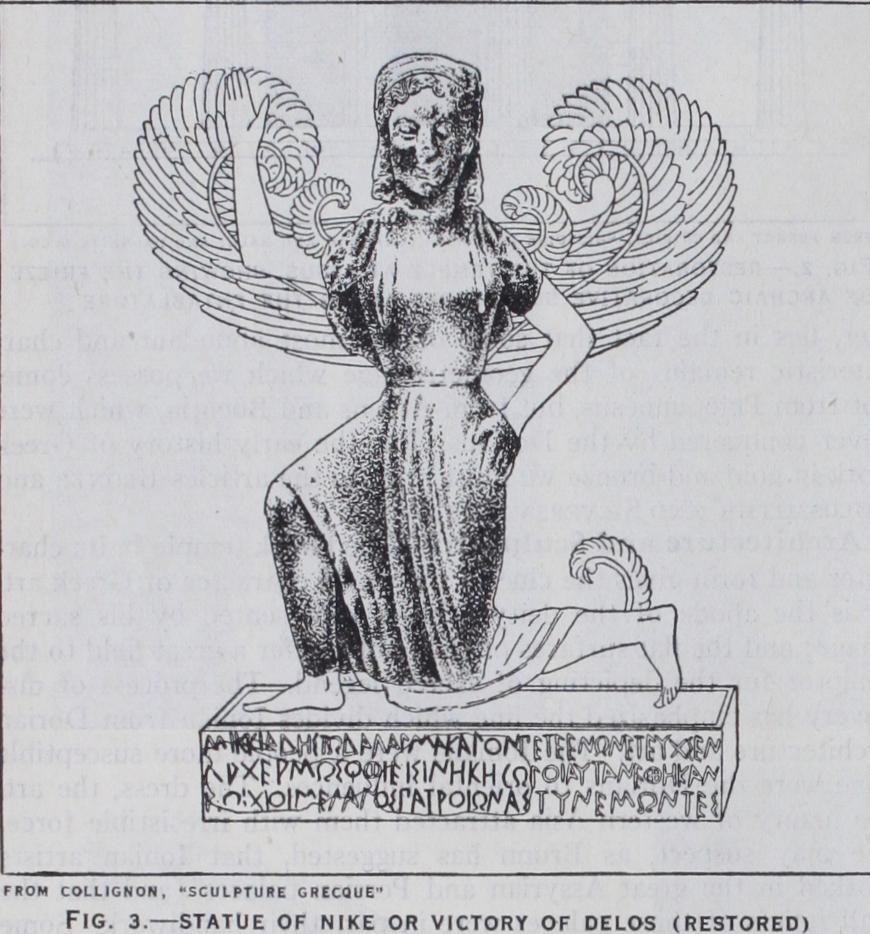

Of the decorative sculpture which adorned these early temples we have more extensive remains than we have of actual construc tion. It will be best to speak of them under their districts. On the coast of Asia Minor, the most extensive series of archaic decora tive sculptures which has come down to us is that which adorned the temple of Assus (fig. 2). These were placed in a unique posi tion on the temple, a long frieze running along the entablature, with representations of wild animals, of centaurs, of Heracles seizing Achelous, and of men feasting, scene succeeding scene without much order or method. The only figures from Miletus which can be considered as belonging to the original temple de stroyed by Darius, are the dedicated seated statues, some of which, brought away by Sir Charles Newton in the middle of the r gth century, are now preserved at the British Museum. At Ephesus J. T. Wood was more successful (1869-74) and recovered con siderable fragments of the temple of Artemis, to which, as Herod otus tells us, Croesus presented many columns. The lower part of one of these columns, bearing figures in relief of early Ionian style, has been put together at the British Museum; and remains of inscriptions recording the presentation by Croesus are still to be traced. Reliefs from a cornice of somewhat later date are also to be found at the British Museum. Among the Aegean islands, Delos has furnished us with the most important remains of early art. French excavators have there found a very early statue of a woman dedicated by one Nicandra to Artemis, a figure which may be instructively compared with another from Samos, dedicated to Hera by Cheramues. The Delian statue is in shape like a flat beam ; the Samian, which is headless, is like a round tree. The arms of the Delian figure are rigid to the sides; the Samian lady has one arm clasped to her breast. A great improvement on these inex pressive figures is marked by another figure found at Delos, and connected, though perhaps incorrectly, with a bases recording the execution of a statue by Archermus and Micciades, two sculptors who stood, in the middle of the 6th century, at the head of a sculptural school at Chios. The representation (fig. 3) is of a running or flying figure, having six wings, like the seraphim in the vision of Isaiah, and clad in long drapery. It may be a statue of Nike or Victory, who is said to have been represented in winged form by Archermus. The figure, with its neatness and precision of work, its expressive face and strong outlines, certainly marks great progress in the art of sculpture. When the early sculpture of Athens is examined, reason is found to think that the Chian school had great influence in that city in the days of Peisistratus.

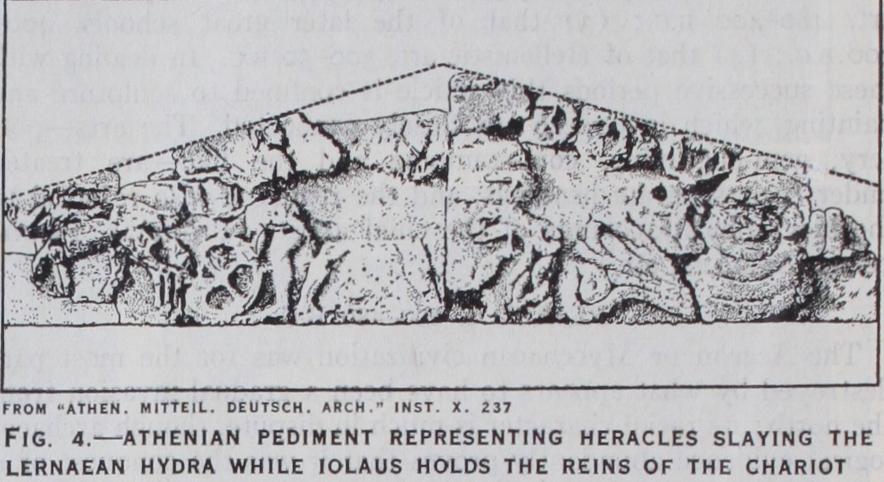

Athenian Sculpture. At Athens, in the age 650-48o, may be traced two quite distinct periods of architecture and sculpture. In the earlier of the two periods, a rough limestone was used alike for the walls and the sculptural decoration of temples ; in the later period it was superseded by marble, whether native or imported. Every visitor to the museum of the Athenian Acropolis stands astonished at the groups which decorated the pediments of Athenian temples before the age of Peisistratus—groups of large size, rudely cut in soft stone, of primitive workmanship, and painted with bright red, blue and green, in a fashion which makes no attempt to follow nature, but only to produce a vivid result. The two largest in scale of these groups seem to have belonged to the pediments of the early 6th century temple of Athena. On other smaller pediments, perhaps belonging to shrines of Heracles and Dionysus, there are conflicts of Heracles with Triton or with other monstrous foes. It is notable how fond the Athenian artists of this early time are of exaggerated muscles and of monstrous forms, which combine the limbs of men and of animals ; the measure and moderation which mark developed Greek art are as completely absent as are skill in execution or power of grouping. Fig. 4 shows a small pediment in which appears in relief the slaying of the Lernaean hydra by Heracles. The hero strikes at the many-headed water-snake, somewhat inappropriately, with his club. Iolaus, his usual companion, holds the reins of the chariot which awaits Heracles after his victory. On the extreme left a huge crab comes to the aid of the hydra.

There can be little doubt that Athens owed its great start in art to the influence of the court of Peisistratus. at which artists of all kinds were welcome. There was a gradual transformation in sculpture, in which the influence of the Chian and other progres sive schools of sculpture was visible, not only in the substitution of island marble for native stone, but in increased grace and truth to nature, in the toning down of glaring colour, and the appearance of taste in composition. A transition between the older and the newer is furnished by the well-known statue of the calf-bearer, an Athenian preparing to sacrifice a calf to the deities, which is made of marble of Hymettus, and in robust clumsiness of forms is not far removed from the limestone pediments. The sacrificer has been commonly spoken of as Hermes or Theseus, but he seems rather to be an ordinary human votary.

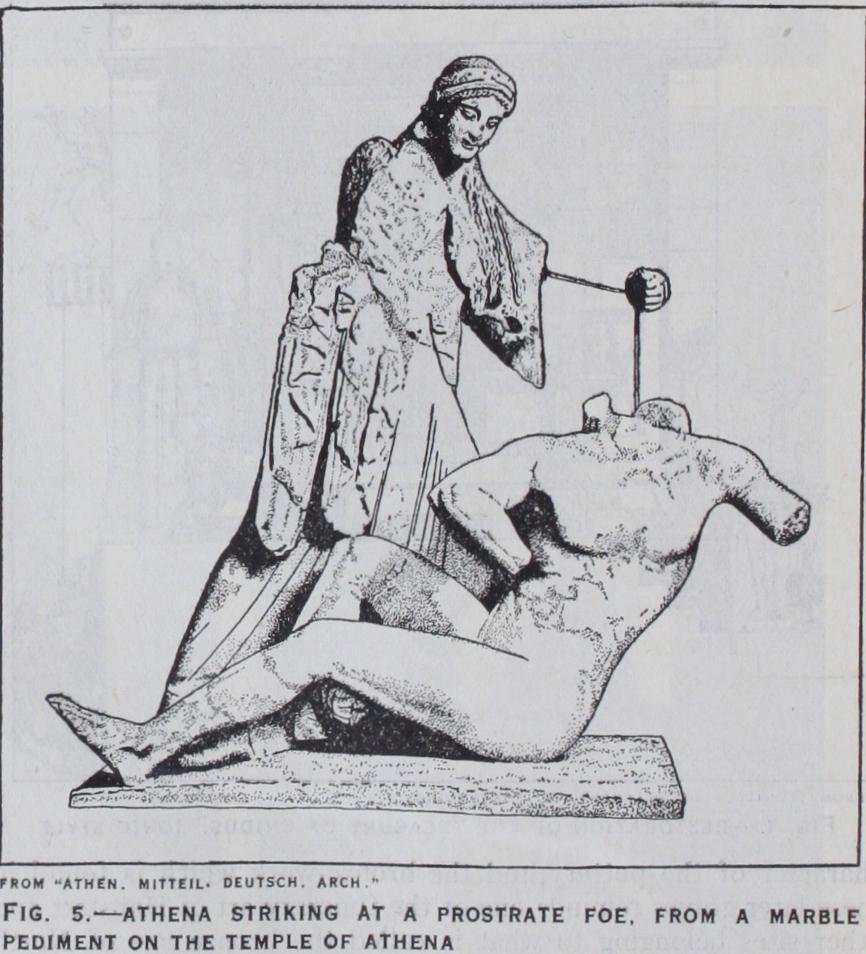

In the time of Peisistratus or his sons a peristyle of columns was added to the old temple of Athena; and this necessitated the preparation of fresh pediments. These were of marble. In one of them was represented the battle between gods and giants ; in the midst Athena her self striking at a prostrate foe (fig. 5) . In these figures no eye can fail to trace remark able progress. On about the same level of art are the charming statues dedicated to Athena, which were set up in the latter half of the 6th century on the Acropolis, whose graceful though conventional forms and delicate colouring make them one of the great attractions of the Acropolis mu seum. We show a figure (fig. 6) which is the work of the sculptor Antenor, who was also author of a celebrated group repre senting the tyrant-slayers, Harmodius and Aristogiton. To the same age belong many other votive reliefs of the Acropolis, rep resenting horsemen, scribes and other votaries of Athena.

Dorian Sculpture. From Athens we pass to the seats of Dorian art. And in doing so we find a complete change of character. In place of draped goddesses and female figures, there are nude male forms. In place of Ionian softness and ele gance, hard, rigid outlines, strong muscular development, a greater love of and faithfulness to the actual human form—the influence of the palaestra rather than of religion. To the known series of archaic male figures modern exploration has added many exam ples. More especially may be mentioned figures from the temple of Apollo Ptoos in Boeotia, probably representing the god himself. Still more noteworthy are two colossal nude figures of Cleobis and Biton remarkable both for force and for rudeness, found at Delphi, the inscriptions of which prove them to be the work of an Argive sculptor. (P1. II., fig. 3.) In the island of Crete was found the upper part of a draped figure, whether male or female is not certain, which should be an example of the early Daedalid school, whence the art of Peloponnesus was derived; it is hardly a char acteristic product of that school; rather the likeness to the dedica tion of Nicandra is striking.

Another remarkable piece of Athenian sculpture, of the time of the Persian Wars, is the group of the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogiton, set up by the people of Athens, and made by the sculptors Critius and Nesiotes. These figures were hard and rigid in outline, but showing some progress in the treatment of the nude. Copies are preserved in the museum of Naples (P1. II., fig. 7).

Olympia, Sparta, Selinus. Next in importance to Athens, as a find-spot for works of early Greek art, ranks Olympia. Olympia, however, did not suffer like Athens from sudden violence, and the explorations there have brought to light a continuous series of remains, beginning with bronze tripods of the geometric age and ending at the barbarian invasions of the 4th century A.D. Notable among the 6th century stone-sculpture of Olympia are the pedi ment of the treasury of the people of Megara, in which is repre sented a battle of gods and giants, and a huge rude head of Hera which seems to be part of the image worshipped in the Heraeum. Its flatness and want of style should be noted.

Among the temples of Greece proper the Heraeum of Olympia stands almost alone for antiquity and interest, its chief rival, be sides the temples of Athens, being the other temple of Hera at Argos. It appears to have been originally constructed of wood, for which stone was by slow degrees, part by part, substituted. In the time of Pausanias one of the pillars was still of oak, and at the present day the varying diameter of the columns and other structural irregularities bear witness to the process of constant renewal which must have taken place. The early small bronzes of Olympia form an important series, figures of deities standing or striding, warriors in their armour, athletes with exaggerated muscles, and women draped in the Ionian fashion, which did not become unpopular in Greece until after the Persian Wars.

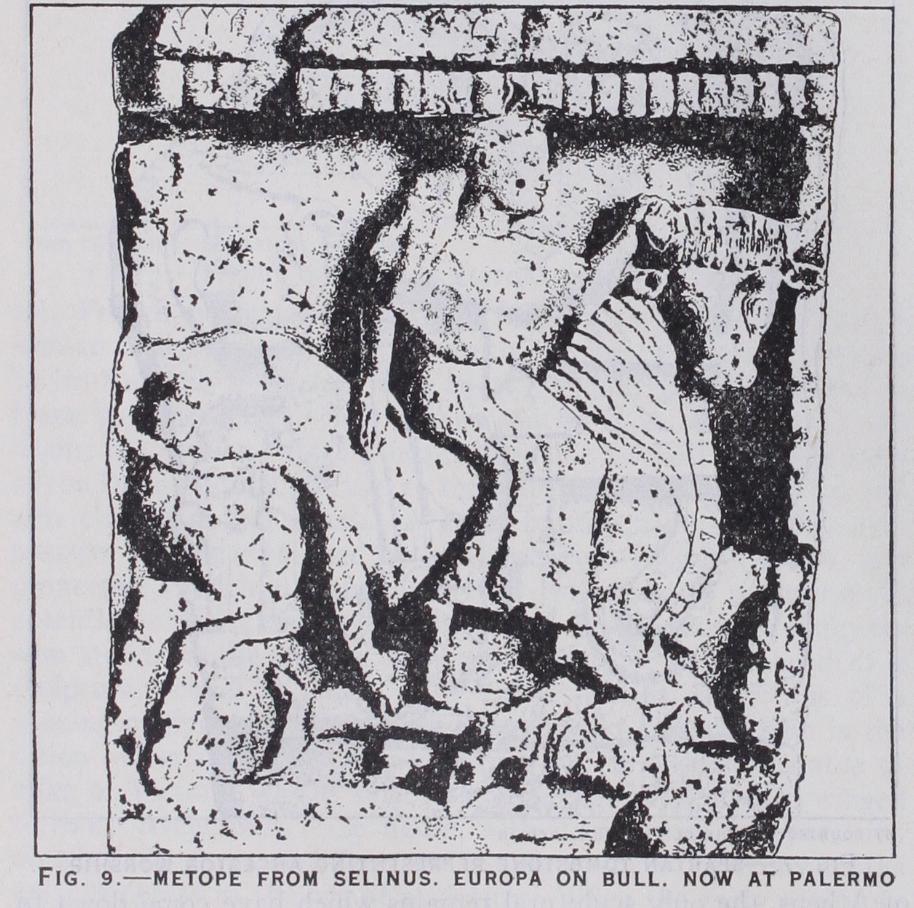

Excavations at Sparta have revealed interesting monuments belonging to the worship of ancestors, which seems in the con servative Dorian states of Greece to have been more strongly developed than elsewhere. On some of these stones, which doubt less belonged to the family cults of Sparta, are shown the ancestor seated holding a wine-cup, accompanied by his faithful horse or dog; on some we see the ancestor and ancestress seated side by side (fig. 7), ready to receive the gifts of their descendants, who appear in the corner of the relief on a much smaller scale. The male figure holds a wine-cup, in allusion to the libations of wine made at the tomb. The female figure holds her veil and the pomegranate, the recognized food of the dead. A huge serpent stands erect behind the pair. The style of these sculptures is as striking as the subject:—lean, rigid forms with severe outline, carved in a very low relief, the surface of which is not rounded but flat. The name of Selinus in Sicily, an early Megarian colony, has long been associated with some of the most curious of early sculptures, the metopes of ancient temples, representing the ex ploits of Heracles and of Perseus. Even more archaic metopes have in recent years been brought to light, one representing a seated sphinx, one the journey of Europa over the sea on the back of the amorous bull, a pair of dolphins swimming beside her. In simplicity and rudeness of work these reliefs remind us of the limestone pediments of Athens (fig. 4), but they are of another and a severer style; the Ionian laxity is wanting.

Delphi. The French excavations at Delphi add a new and im portant chapter to the history of 6th century art. Of the archaic temple of Apollo, built as Herodotus tells us by the Alcmaeonidae of Athens, the only sculptural remains which have come down to us are some fragments of the pedimental figures. Of the treasuries which contained the offerings of the pious at Delphi, the most archaic of which there are remains is that belonging to the people of Sicyon. To it appertains a set of exceedingly primitive metopes. One depicts Idas and the Dioscuri driving off cattle (Pl. IV., fig. 5) ; another, the ship Argo; another, Europa on the bull, others merely animals, a ram or a boar. The treasury of the people of Cnidus (or perhaps Siphnos) is in style some half a century later (see fig. I). To it belongs a long frieze representing a variety of curious subjects : a battle, perhaps between Greeks and Trojans, with gods and goddesses looking on; a gigantomachy in which the figures of Poseidon, Athena, Hera, Apollo, Artemis and Cybele can be made out, with their opponents, who are armed like Greek hoplites ; Athena and Heracles in a chariot; the carrying off of the daughters of Leucippus by Castor and Pollux; Hephaestus with his fire. The treasury of the Athenians, erected at the time of the Persian Wars, was adorned with metopes of singularly clear-cut and beautiful style, but very fragmentary, representing the deeds of Heracles and Theseus.

The most interesting and important of all Greek archaic sculp tures are the pediments of the temple at Aegina (q.v.) . These groups of nude athletes fighting over the corpses of their com rades are preserved at Munich, and are familiar to artists and students. But the very fruitful excavations of Prof. Furtwangler put them in quite a new light. Furtwangler (Aegina: Heiligtum der Aphaia) entirely rearranged these pediments, in a way which removed the extreme simplicity and rigour of the composition, and introduced far greater variety of attitudes and motive. We repeat here these new arrangements (fig. 8), the reasons for which must be sought in Furtwangler's great publication. The individual figures are not much altered, as the restorations of Thorwaldsen, even when incorrect, have now a prescriptive right of which it is not easy to deprive them. Beside the pediments of Aegina must be set the remains of the pediments of the temple of Apollo at Eretria in Euboea, the chief group of which (P1. I., fig. 4), Theseus carrying off an Amazon, is one of the most finely ex ecuted works of early Greek art.

The most marvellous phenomenon in the whole history of art is the rapid progress made by Greece in painting and sculpture during the 5th century B.C. As in literature the 5th century takes us from the rude peasant plays of Thespis to the drama of Soph ocles and Euripides; as in philosophy it takes us from Pythagoras to Socrates ; so in sculpture it covers the space from the primitive works made for the Peisistratidae to some of the most perfect productions of the chisel.

In architecture the 5th century is ennobled by the Theseum, the Parthenon and the Erechtheum, the temples of Zeus at Olympia, of Apollo at Phigalia, and many other central shrines, as well as by the Hall of the Mystae at Eleusis and the Propylaea of the Acropolis. Some of the most important of the Greek tem ples of Italy and Sicily, such as those of Segesta and Selinus, date from the same age. It is, however, only of their sculptural decorations, carried out by the greatest masters in Greece, that we need here treat in any detail.

Painting.

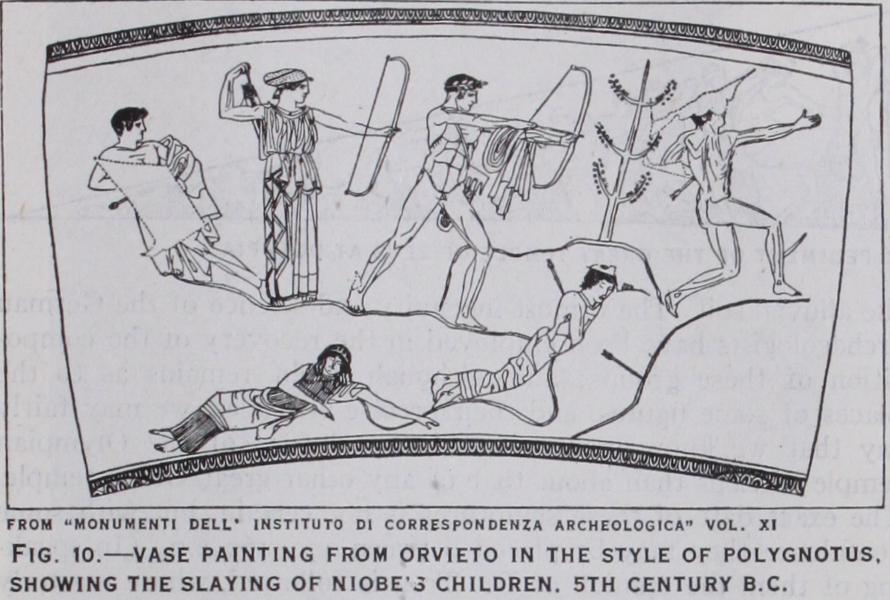

It is the rule in the history of art that innovations and technical progress are shown earlier in the case of painting than in that of sculpture, a fact easily explained by the greater ease and rapidity of the brush compared with the chisel. That this was the order of development in Greek art cannot be doubted. But our means for judging of the painting of the 5th century are very slight. The noble paintings of such masters as Polygnotus, Micon and Panaenus, which once adorned the walls of the great porticos of Athens and Delphi, have disappeared. There remain only the designs drawn rather than painted on the beautiful vases of the age, which in some degree help us to realize, not the colour ing or the charm of contemporary paintings, but the principles of their composition and the accuracy of their drawing.

Polygnotus of Thasos was regarded by his compatriots as a great ethical painter. His colouring and composition were alike very simple, his figures quiet and statuesque, his drawing careful and precise. He won his fame largely by incorporating in his works the best current ideas as to mythology, religion and morals. In particular his painting of Hades with its rewards and punish ments, which was on the walls of the building of the people of Cnidus at Delphi, might be considered as a great religious work, parallel to the paintings of the Campo Santo at Pisa or to the painted windows of such churches as that at Fairford. But he also introduced improvements in perspective and greater freedom in grouping.

It is fortunate for us that the Greek traveller Pausanias has left very careful and detailed descriptions of some of the most important of the frescoes of Polygnotus, notably of the Taking of Troy and the Visit to Hades, which were at Delphi. A com parison of these descriptions with vase paintings of the middle of the 5th century has enabled us to discern with great probability the principles of Polygnotan drawing and perspective. Prof. Robert has even ventured to restore the paintings on the evidence of vases. There is represented one of the scenes depicted on a vase found at Orvieto (fig. io), which is certainly Polygnotan in character. It represents the slaying of the children of Niobe by Apollo and Artemis. Here may be observed a remarkable perspec tive. The different heights of the rocky background are repre sented by lines traversing the picture on which the figures stand; but the more distant figures are no smaller than the nearer. The forests of Mount Sipylus are represented by a single conventional tree. The figures are beautifully drawn, and full of charm; but there is a want of energy in the action.

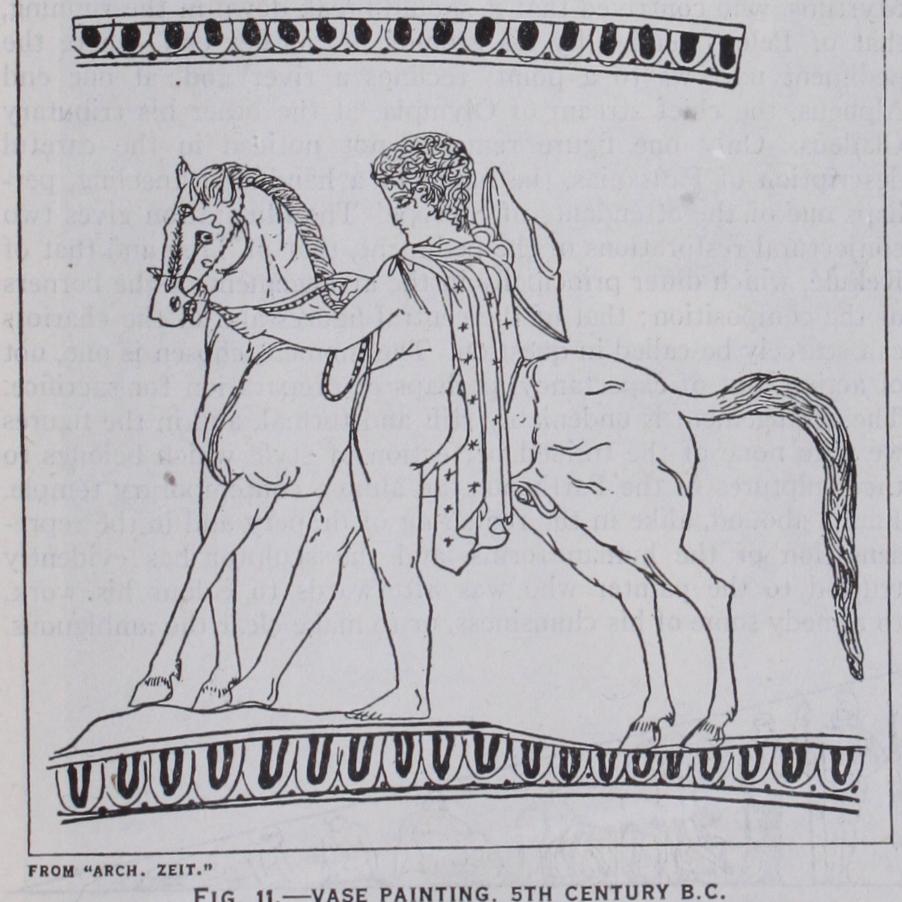

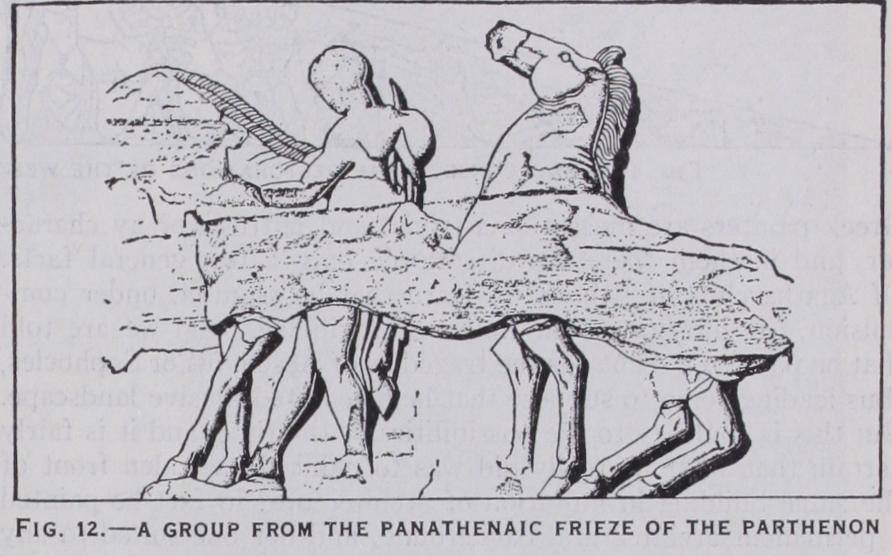

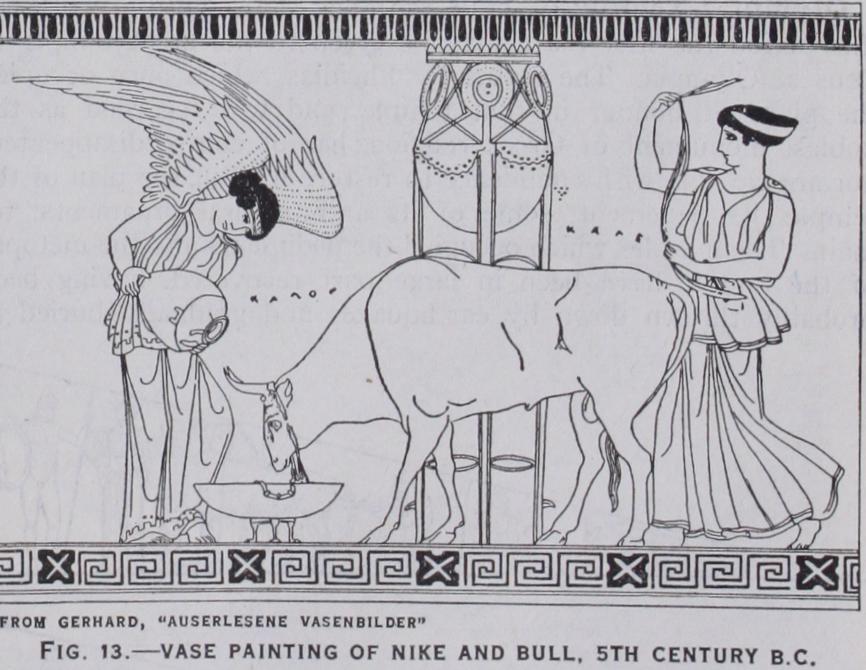

There can be little doubt that the school of Polygnotus exer cised great influence on contemporary sculpture. Panaenus, brother of Pheidias, worked with Polygnotus, and many of the groupings found in the sculptures of the Parthenon remind us of those usual with the Thasian master. At this simple and early stage of art there was no essential difference between fresco-paint ing and coloured relief, light and shade and aerial perspective being unknown. Two vase-paintings are shown, one (fig. I I), a group of man and horse which closely resembles figures in the Panathe naic frieze of the Parthenon (fig. 12) ; the other (fig. 13), repre senting Victory pouring water for a sacrificial ox to drink, which reminds us of the balustrade of the shrine of Wingless Victory at Athens.

Most writers on Greek painting have supposed that after the middle of the 5th century the technique of painting rapidly im proved. This may well have been the case ; but there is little means of testing the question. Such improvements would soon raise such a barrier between fresco-painting and vase-painting which by its very nature must be simple and architectonic—that vases can no longer be used with confidence as evidence for con temporary painting. The stories told us by Pliny of the lives of Greek painters are mostly of a trivial and untrustworthy charac ter, and in them there are discernible only a few general facts. Of Agatharchus of Athens we learn that he painted, under com pulsion, the interior of the house of Alcibiades, and we are told that he painted a scene for the tragedies of Aeschylus or Sophocles, thus leading some to suppose that he attempted illusive landscape. But this is contrary to the possibilities of the time, and it is fairly certain that what he really did was to paint the wooden front of the stage building in imitation of architecture ; in fact he painted a permanent architectural background, and not one suited to any particular play. Of other painters who flourished at the end of the century, such as Zeuxis and Aristides, it will be best to speak under the next period.

It is now generally held, in consequence of evidence furnished by tombs, that the 5th century saw the end of the making of vases on a great scale at Athens for export to Italy and Sicily. And, in fact, few things in the history of art are more remarkable than the rapidity with which vase-painting at Athens reached its highest point and passed it on the downward road. At the begin ning of the century black-figured ware was scarcely out of fashion, and the masters of the severe red-figured style, Pamphaeus, Epic tetus and their contemporaries, were in vogue. The schools of Euphronius, Hiero and Duris belong to the age of the Persian wars. With the middle of the century the works of these makers are succeeded by unsigned vases of most beautiful design, some of them showing the influence of Polygnotus. In the later years of the century, when the empire of Athens was approaching its fall, drawing becomes laxer and more careless, and in the treatment of drapery we frequently note the over-elaboration of folds, the want of simplicity, which begin to mark contemporary sculpture.

Olympia : Temple of Zeus.

Among the sculptural works of this period the first place may be given to the great temple of Zeus at Olympia. The statue by Pheidias, which once occupied the place of honour in that temple, and was regarded as the noblest monument of Greek religion, has of course disappeared, nor are we able with confidence to restore it. But the plan of the temple, its pavement, some of its architectural ornaments, re main. The marbles which occupied the pediments and the metopes of the temple have been in large part recovered, having been probably thrown down by earthquakes and gradually buried in the alluvial soil. The utmost ingenuity and science of the German archaeologists have been employed in the recovery of the compo sition of these groups; and, although doubt remains as to the places of some figures, and their precise attitudes, we may fairly say that we know more about the sculpture of the Olympian temple of Zeus than about that of any other great Greek temple. The exact date of these sculptures is not certain, but with some confidence they may be placed between 470-46o B.C. (In speak ing of them the opinion of Dr. Treu is followed, whose masterly work in vol. iii. of the great German publication on Olympia is a model of patience and of science.) In the eastern pediment (fig. , as Pausanias tells us, were represented the preparations for the chariot-race between Oenomaus and Pelops, the result of which was to determine whether Pelops should find death or a bride and a kingdom. In the midst, invisible to the contending heroes, stood Zeus the supreme arbiter. On one side of him stood Oenomaus with his wife Sterope, on the other Pelops and Hippodameia, the daughter of Oenomaus, whose position at once indicates that she is on the side of the newcomer, whatever her parents may feel. Next on either side are the four-horse chariots of the two com petitors, that of Oenomaus in the charge of his perfidious groom Myrtilus, who contrived that it should break down in the running, that of Pelops tended by his grooms. At either end, where the pediment narrows to a point, reclines a river god, at one end Alpheus, the chief stream of Olympia, at the other his tributary Cladeus. Only one figure remains, not noticed in the careful description of Pausanias, the figure of a handmaid kneeling, per haps one of the attendants of Sterope. The illustration gives two conjectural restorations of the pediment, that of Treu and that of Kekule, which differ principally in the arrangement of the corners of the composition ; that of the central figures and of the chariots can scarcely be called in question. The moment chosen is one, not of action, but of expectancy, perhaps of preparation for sacrifice. The arrangement is undeniably stiff and formal, and in the figures we note none of the trained perfection of style which belongs to the sculptures of the Parthenon, an almost contemporary temple. Faults abound, alike in the rendering of drapery and in the repre sentation of the human forms, and the sculptor has evidently trusted to the painter who was afterwards to colour his work, to remedy some of his clumsiness, or to make clear the ambiguous.

Nevertheless there is in the whole a dignity, a sobriety and a sim plicity, which reconcile us to the knowledge that this pediment was certainly regarded in antiquity as a noble work, fit to adorn even the palace of Zeus. In the western pediment (fig. 14), the subject is the riot of the Centaurs when they attended the wed ding of Peirithous in Thessaly, and, attempting to carry off the bride and her comrades, were slain by Peirithous and Theseus. In the midst of the pediment, invisible like Zeus in the eastern pediment, stands Apollo, while on either side of him Theseus and Peirithous attack the Centaurs with weapons hastily snatched. Our illustration gives two possible arrangements. The monsters are in various attitudes of attempted violence, of combat and defeat; with each grapples one of the Lapith hero?s in the en deavour to rob them of their prey. In the corners of the pediment recline female figures, perhaps attendant slaves, though the farthest pair may best be identified as local Thessalian nymphs, looking on with the calmness of divine superiority, yet not wholly unconcerned in what is going forward. Though the composition of the two pediments differs notably, the one bearing the impress of a parade-like repose, the other of an overstrained activity, the style and execution are the same in both, and the shortcomings must be attributed to the inferior skill of a local school of sculp tors compared with those of Athens or of Aegina. It even appears likely that the designs also belong to a local school. Pausanias, it is true, says that the pediments were the work of Alcamenes, the pupil of Pheidias, and of Paeonius, a sculptor of Thrace, respec tively ; but it is almost certain that he was misled by the local guides, who would naturally be anxious to connect the sculptures of their great temple with well-known names.

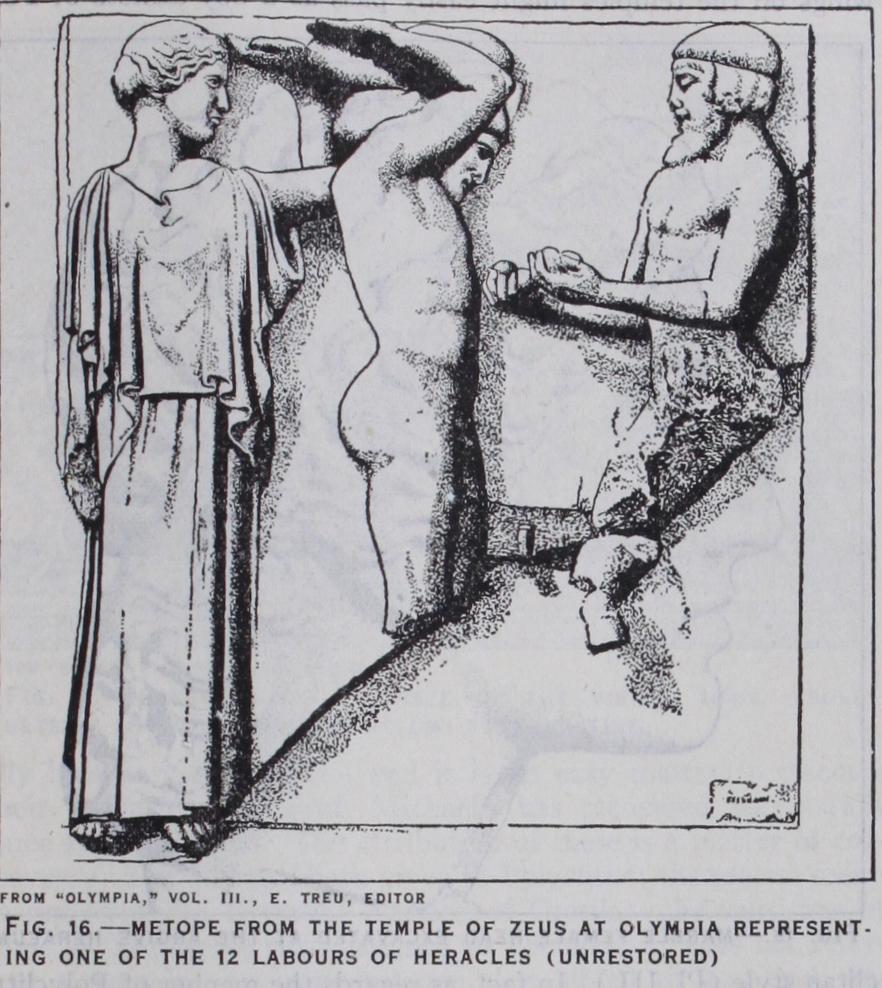

The metopes of the temple are in the same style of art as the pediments, but the defects of awkwardness and want of mastery are less conspicuous, because the narrow limits of the metope exclude any elaborate grouping. The subjects are provided by the i 2 labours of Heracles; the figures introduced in each metope are but two or at most three; and the action is simplified as much as possible. The example shown (fig. 16), represents Heracles holding up the sky on a cushion, with the friendly aid of a Hes perid nymph, while Atlas, whom he has relieved of his usual burden, approaches bringing the apples which it was the task of Heracles to procure.

Another of the fruits of the excavations of Olympia is the Floating Victory by Paeonius, unfortunately faceless (fig. 17), which was set up in all probability in memory of the victory of the Athenians and their Messenian allies at Sphacteria in 425 B.c. The inscription states that it was dedicated by the Messenians and people of Naupactus from the spoils of their enemies, but the name of the enemy is not mentioned in the inscription. The statue of Paeonius, which comes floating down through the air with drapery borne backward, is of a bold and innovating type, and its influence may be traced in many works of the next age.

Delphic Charioteer.

Among the discoveries at Delphi none is so striking and valuable to us as the life-size statue in bronze of a charioteer holding in his hand the reins. Homolle maintained this to be part of a chariot-group set up by Polyzalus, brother of Gelo and Hiero of Syracuse, in honour of a victory won in the chariot-race at the Pythian games at Delphi (fig. 18). The char ioteer is evidently a high-born youth, and is clad in the long chiton which was necessary to protect a driver of a chariot from the rush of air. The date would be about 48o-47o B.C. Bronze groups representing victorious chariots with their drivers were among the noblest and most costly dedications of antiquity; the present figure is our only satisfactory representative of them. In style the figure is very notable, tall and slight beyond all con temporary examples. The contrast between the conventional de corousness of face and drapery and the lifelike accuracy of hands and feet is very striking, and indicates the clashing of various tendencies in art at the time when the great style was formed in Greece.

Myron.

The three great masters of the 5th century, Myron, Pheidias and Polyclitus are all in some degree known to us from their works. Of Myron we have copies of two works, the Marsyas with Athena (Pl. II., fig. 8), and the Discobolus. The Marsyas (a copy in the Lateran Museum) represents the Satyr so named in the grasp of conflicting emotions, eager to pick up the flutes which Athena has thrown down, but at the same time dreading her dis pleasure if he does so. More recently the Athena also has been identified. The Discobolus has usually been judged from the examples in the Vatican and the British Museum, in which the anatomy is modernized and the head wrongly put on. There are now photographs of the very perior replica in the Lancelotti gallery at Rome, the pose of which is much nearer to the original. The illustration represents a toration made at Munich, by bining the Lancelotti head with the Vatican body (P1. II., fig. 6) .

Pheidias.

Of the works of Pheidias we have unfortunately no certain copy, excepting the small replicas at Athens of his Athena Parthenos. The larger of these was found in t 88o : it is very clumsy, and the wretched device by which a pillar is introduced to support the Victory in the hand of Athena can scarcely be sup posed to have belonged to the great original. Tempting theories have been published by Furt wangler (Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture) and other archaeologists, which identify copies of the Athena Lemnia of Pheidias, his Pantarces, his Aphrodite Urania and other statues; but doubt hangs over all these attributions.A more pertinent and more promising question is, how far one may take the decorative sculpture of the Parthenon, since Lord Elgin's time the pride of the British Museum, as the actual work of Pheidias, or as done from his designs. Here again we have no conclusive evidence; but it appears from the testimony of in scriptions that the pediments at all events were not executed until after Pheidias's death.

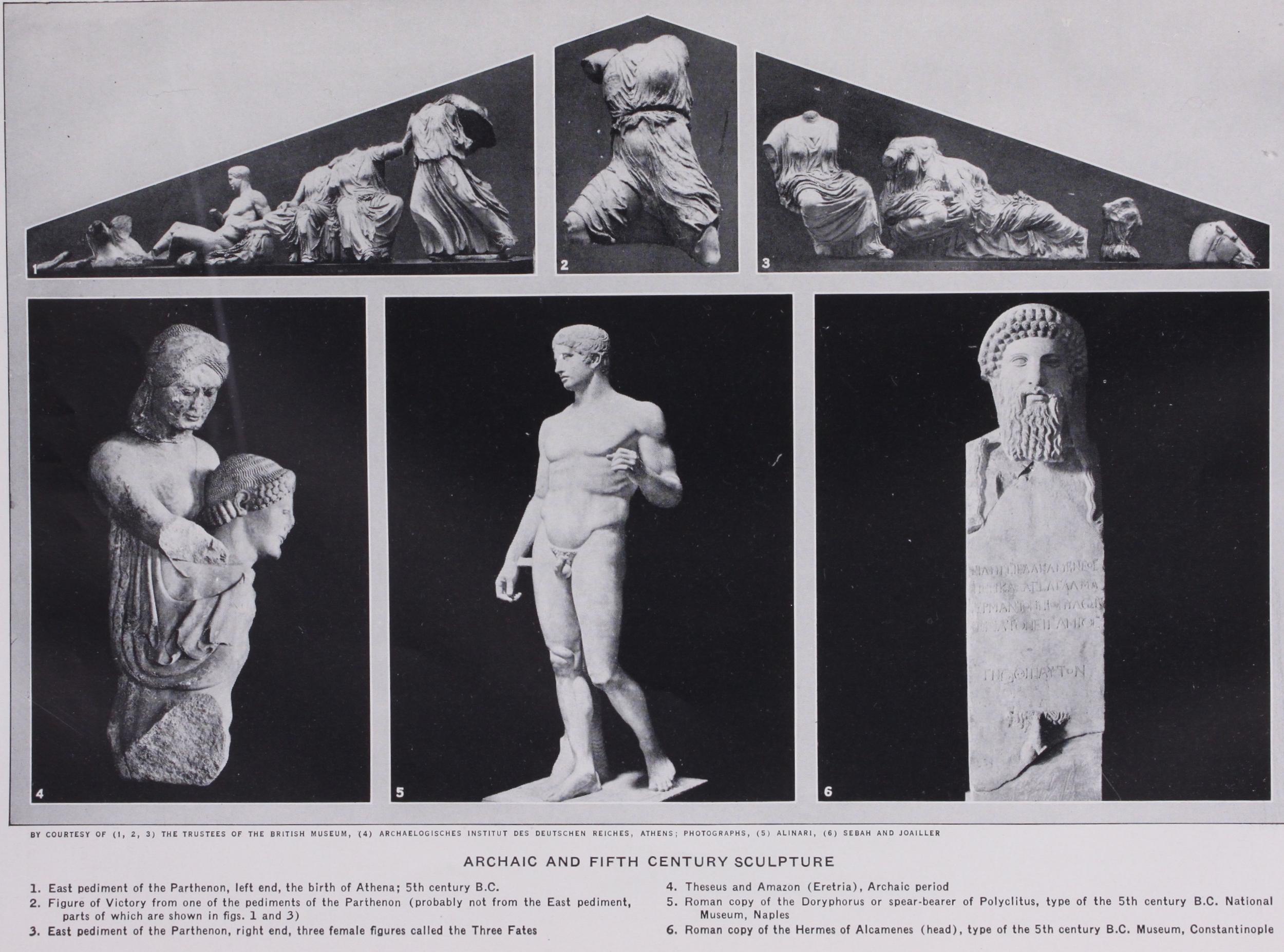

Of course, the pediments and frieze of the Parthenon (q.v.), whose work soever they may be, stand at the head of all Greek decorative sculpture. Whether we regard the grace of the com position, the exquisite finish of the statues in the round, or the de lightful atmosphere of poetry and religion which surrounds these sculptures, they rank among the masterpieces of the world. The Greeks esteemed them far below the statue which the temple was made to shelter ; but to us, who have lost the great figure in ivory and gold, the carvings of the casket which once contained it are a perpetual source of instruction and delight. The whole is repro duced by photography in A. S. Murray's Sculptures of the Parthenon.

An abundant literature has sprung up in regard to these sculp tures, but it will suffice here to mention the discussions in Furt wangler's Masterpieces, and the very ingenious attempts of Sauer to determine by a careful exam ination of the bases and back grounds of the pediments as they now stand how the figures must have been arranged in them. The two ends of the eastern pedi ment (P1. I., figs. 1, 2, 3) , are the only fairly well-preserved part of the pediments.

Among the pupils of Pheidias who may naturally be supposed to have worked on the sculptures of the Parthenon, the most no table were Alcamenes and Agora critus. Some fragments remain of the great statue of Nemesis at Rhamnus by Agoracritus, and an interesting light has been thrown on Alcamenes by the dis covery at Pergamum of a pro fessed copy of his Hermes set up at the entrance to the Acropolis at Athens (Pl. I., fig. 6). This, however, is conventional and archaistic in style, and we can scarcely regard it as typical of the master. Another noted con temporary who was celebrated mainly for his portraits was Cresilas, a Cretan. Several copies of his portrait of Pericles exist, and testify to the lofty and idealizing style of portraiture in this great age.

There have been found also admirable sculpture belonging to the other important temples of the Acropolis, the Erechtheum and the temple of Nike. The temple of Nike is the earlier, being pos sibly a memorial of the Spartan defeat at Sphacteria. The Erech theum belongs to the end of our period, and embodies the delicacy and finish of the conservative school of sculpture at Athens just as the Parthenon illustrates the ideas of the more progressive school. The reconstruction of the Erechtheum has been a task which has long occupied the attention of archaeologists (see the paper by Stevens in the American Journal of Archaeology, 1906). The illustration (Pl. IV., fig. 9), shows one of the maidens, called both Corae and Caryatides, who support the entablature of the south porch of the Erechtheum, in her proper setting. This use of the female figure in place of a pillar is based on old Ionian precedent (see fig. I), and is not altogether happy; but the idea is carried out with remarkable skill, the perfect repose and solid strength of the maiden being emphasized.

Polyclitus.

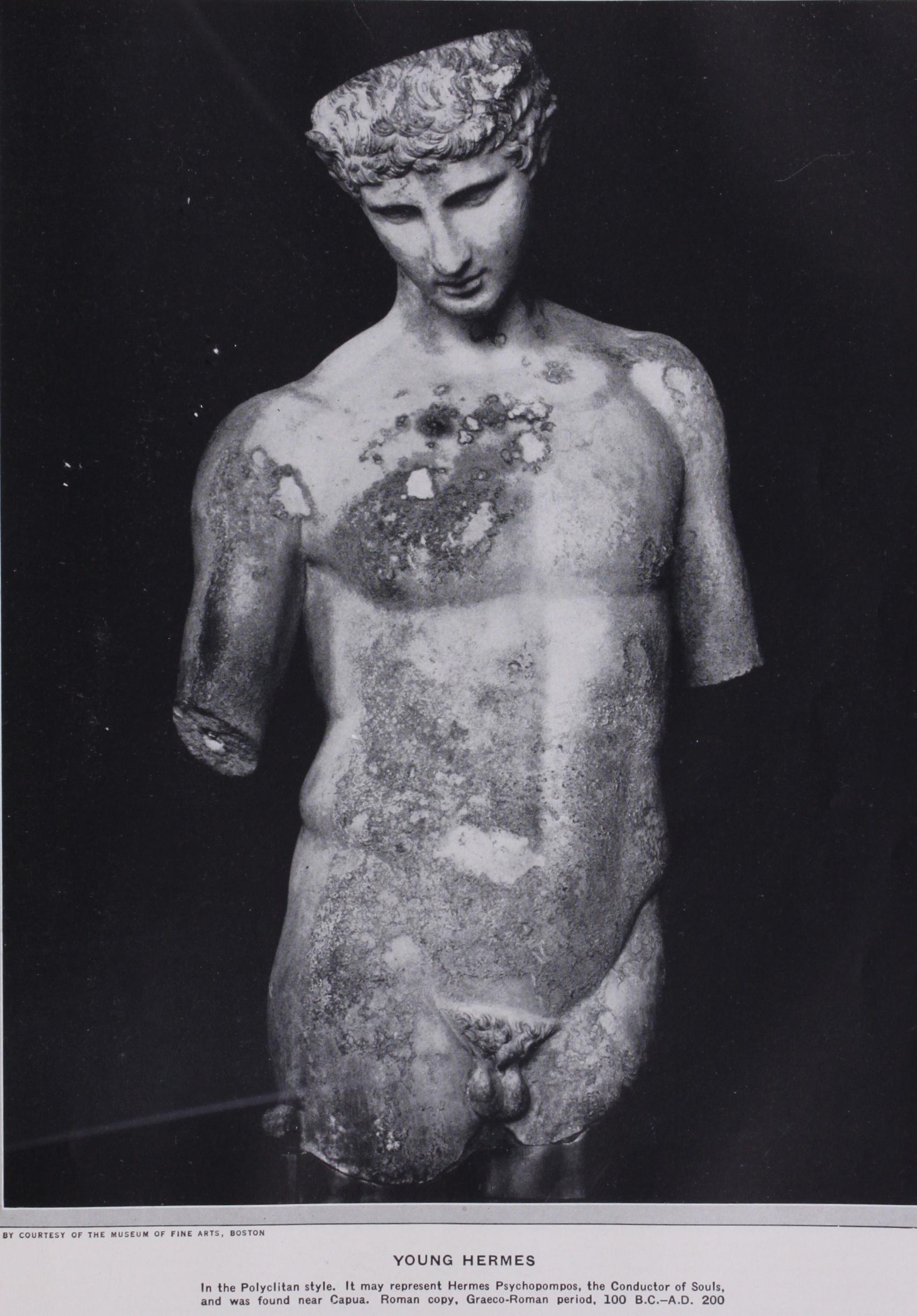

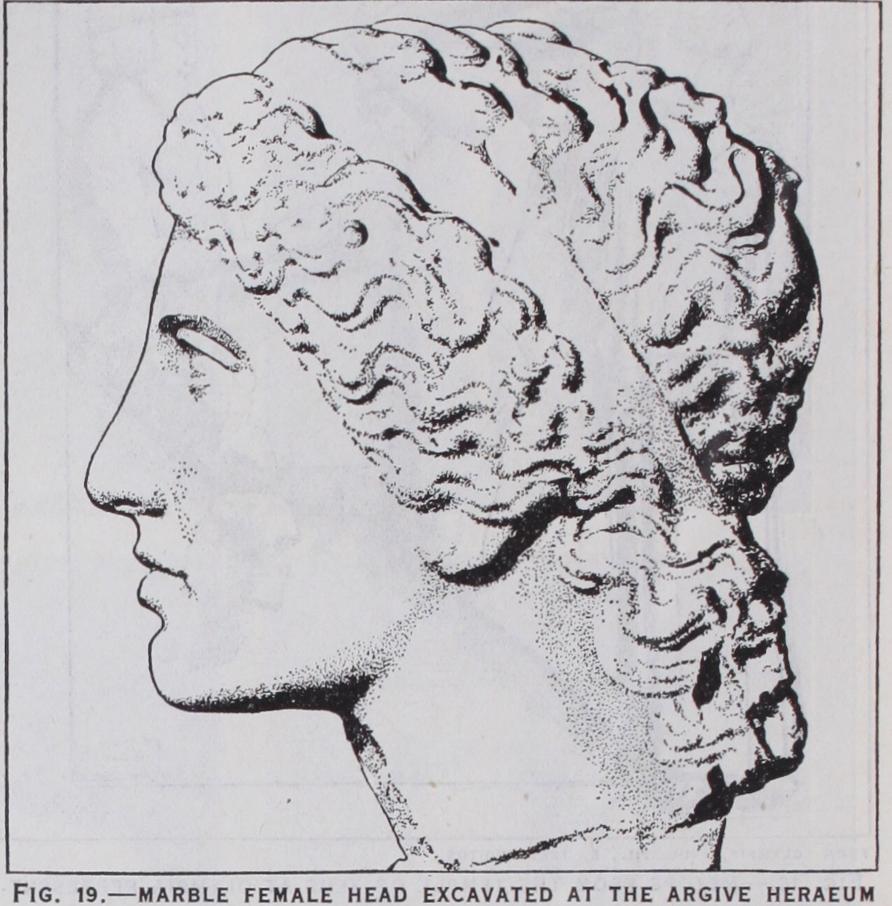

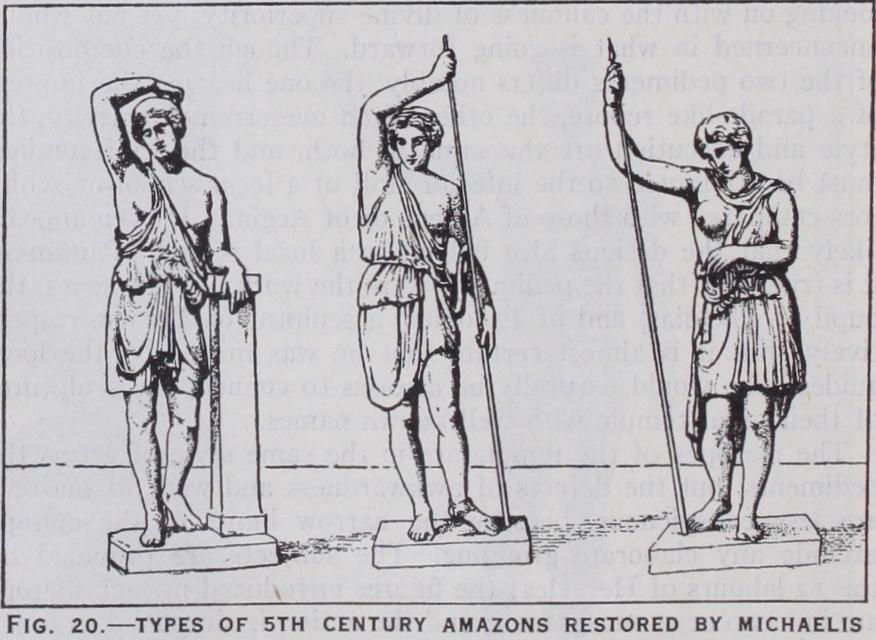

Beside Pheidias of Athens must be placed the greatest of early Argive sculptors, Polyclitus. His two typical athletes, the Doryphorus or spear-bearer (P1. I., fig. 5), and the Diadumenus, have long been identified, and though the copies are not first-rate, they recover the principles of the master's art. Among the bases discovered at Olympia, whence the statues had been removed, are three oz four which bear the name of Poly clitus, and the definite evidence furnished by these bases as to the position of the feet of the statues which they once bore has en abled archaeologists, especially Furtwangler, to identify copies of those statues among known works. Copies of Polyclitan works have also been discovered, and at Delos was found a copy of the Diadumenus, which is of much finer work than the statue in the British Museum from Vaison. The Boston Museum of fine arts has a very beautiful statue of a young Hermes, who but for the wings on the temples might easily pass as a boy athlete of Poly clitan style (Pl. III.). In fact, as regards the manner of Polyclitus besides Roman copies of the Doryphorus and Diadumenus, there is quite a gallery of athletes, boys and men, who all claim relation ship, nearer or more remote, to the school of the great Argive master, and in the Ashmolean museum is a very beautiful bronze head of the Polyclitan school (Pl. IV., fig. 6) . It might have been hoped that the excavations, made under the leadership of Prof. Waldstein (Walston) at the Argive Heraeum, would have brought enlightenment to us as to the style of Polyclitus. Just as the sculptures of the Parthenon are the best monument of Pheidias, so it might seem likely that the sculptural decoration of the great temple which contained the Hera of Polyclitus would show us at large how his school worked in marble, but unfor tunately the fragments of sculpture from the Heraeum are few. The most remarkable is a female head, which may perhaps come from a pediment (fig. 19). But archaeologists are not in agree ment whether it is Polyclitan in style or whether it rather resem bles in style Attic works. Other heads and some highly-finished fragments of bodies come apparently from the metopes of the same temple. (See also ARCOS.) Another work of Polyclitus was his Amazon, made it is said in competition with his great contemporaries, Pheidias, Cresilas and Phradmon, all of whose Amazons were preserved in the great temple of Artemis at Ephesus. In the museums are many statues of Amazons representing 5th century originals. These have usu ally been largely restored, and it is no easy matter to discover their original type. Prof. Michaelis has recovered successfully three types (fig. 2o). The attribution of these is a matter of con troversy. The first has been given to Polyclitus; the second seems to represent the Wounded Amazon of Cresilas; the third has by some archaeologists been assigned to Pheidias. It does not repre sent a wounded Amazon, but one alert, about to leap upon her horse with the help of a spear as a leaping pole.

Lycia.

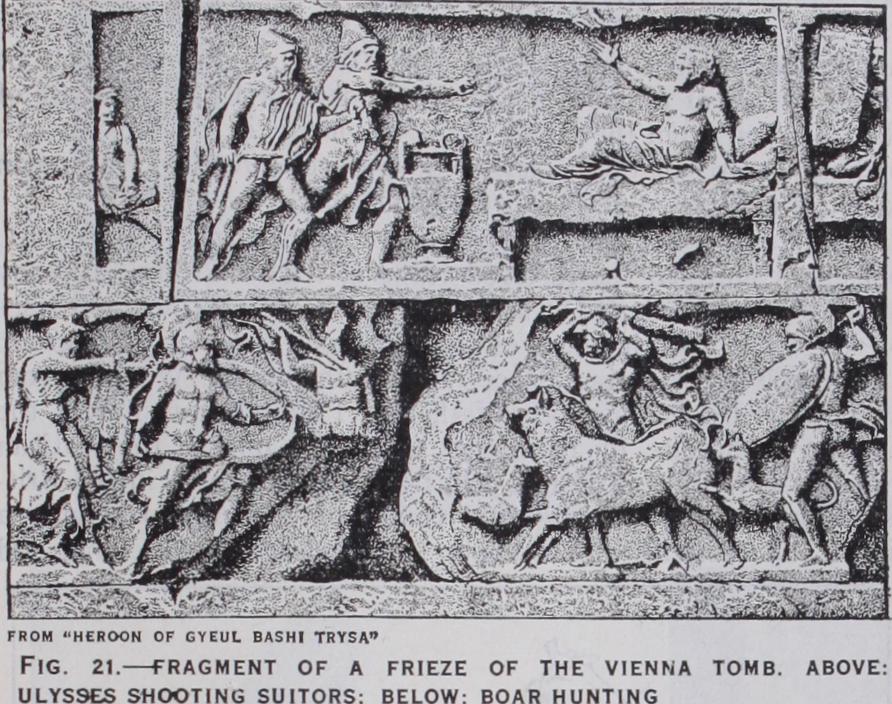

It is impossible to devote little more than a passing mention to the sculpture of other temples and shrines of the later 5th century, which nevertheless deserve careful study. The frieze from the temple of Apollo at Phigalia, representing Centaur and Amazon battles, is familiar to visitors of the British Museum, where, however, its proximity to the remains of tire Parthenon lays stress upon the faults of grouping and execution which this frieze presents. It seems to be the work of local Arcadian artists. More pleasing is the sculpture of the Ionic tomb called the Nereid monument, brought by Sir Charles Fellows from Lycia. Here we have not only a series of bands of relief which ran round the tomb, but also detached female figures, whence the name which it bears is derived, though these women with their fluttering drapery may be not nymphs of the sea, but personifications of sea-breezes.Lycian sculpture is well represented by the friezes, now in the Vienna Museum, which adorned a heroon near Gyeul Bashi and date from not much later than the middle of the 5th century. In the midst of the enclosure was a tomb, and the walls of the en closure itself were adorned within and without with a great series of reliefs, mostly of mythologic purport. Many subjects which but rarely occur in early Greek art, the siege of Troy, the ad venture of the Seven against Thebes, the carrying off of the daughters of Leucippus, Ulysses shooting down the Suitors, are here represented in detail. Prof. Benndorf, who has published these sculptures in an admirable volume, is disposed to see in them the influence of the Thasian painter Polygnotus. Anyone can see their kinship to painting, and their subjects recur in some of the great frescoes painted by Polygnotus, Micon and others for the Athenians. Like other Lycian sculptures, they contain non Hellenic elements ; in fact Lycia forms a link of the chain which extends from the wall-reliefs of Assyria to works like the columns of Trajan and of Antoninus,but is not embodied in the more purely idealistic works of the highest Greek art. A small part of the frieze of the Vienna tomb/is shown in fig. 2 r ; in this fragment are two scenes, one directly above the other ; in the upper Ulysses, accompanied by his son Telemachus, is in the act of shooting the suitors, who are reclining at table in the midst of a feast; a cup bearer, possibly Melanthius, is escaping by a door behind Ulysses; and in the lower is the central group of a frieze representing the hunting of the Calydonian boar, the boar being shown—as is usual in the best period of Greek art—as an ordinary animal and no monster.

Portraits.

Archaeologists formerly paid little attention to an interesting branch of Greek art, that of sculptured portraits, but the known portraits of the 5th century now include Pericles, Herodotus, Thucydides, Anacreon, Sophocles, Euripides, Socrates and others. As might be expected in a time when style in sculpture was so strongly pronounced, these portraits, as we may see from later copies, are notably ideal. They represent the great men whom they portray not in the spirit of realism. Details are neg lected, expression is not elaborated ; the sculptor tries to repre sent what is permanent in his subject rather than what is tempo rary. Hence these portraits do not seem to belong to a particular time of life; they only represent a man in the perfection of physi cal force and mental energy. And the race or type is clearly shown through individual traits. In some cases it is still disputed whether statues of this age represent deities or mortals, so notable are the repose and dignity which even human figures acquire under the hands of 5th century masters. The Pericles after Cresilas in the British Museum and the athlete-portraits of Polyclitus, are good The high ideal level attained by Greek art at the end of the 5th century is maintained in the 4th. There cannot be any ques tion of decay in it save at Athens, where undoubtedly the loss of religion and the decrease of national prosperity acted prejudi cially. But in Peloponnesus the time was one of expansion ; sev eral new and important cities, such as Messene, Megalopolis and Mantinea, arose under the protection of Epaminondas. And in Asia the Greek cities were still prosperous and artistic, as were the cities of Italy and Sicily which kept their independence. On the whole there is during this age some diminution of the freshness and simplicity of art ; it works less in the service of the gods and more in that of private patrons; it becomes less ethical and more sentimental and emotional. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that technique both in painting and sculpture advanced with rapid strides; artists had a greater mastery of their materials, and ventured on a wider range of subject.In the 4th century no new temples of importance rose at Athens; the Acropolis had taken its final form ; but at Messene, Tegea, Epidaurus and elsewhere, very admirable buildings arose. The remains of the temple at Tegea are of wonderful beauty and finish; as are those of the theatre and the so-called Tholus of Epidaurus. In Asia Minor vast temples of the Ionic order arose, especially at Miletus and Ephesus. The colossal pillars of Miletus astonish the visitors to the Louvre ; while the sculptured columns of Ephesus in the British Museum (Pl. IV., fig. 8), show a high level of artistic skill. The Mausoleum erected about 35o B.C. at Halicarnassus in memory of Mausolus, king of Caria, and adorned with sculpture by the most noted artists of the day, was reck oned one of the wonders of the world. It has been in part restored in the British Museum, where also are models of various con jectural restorations. A small part of the sculptural decoration representing a battle between Greeks and Amazons is shown (Pl. IV., figs. t and 2), wherein the energy of the action and the careful balance of figure against figure are remarkable. We pos sess also the fine portraits of Mausolus himself and his wife Artemisia, which stood in or on the building, as well as part of a gigantic chariot with four horses which surmounted it.

Another architectural work of the 4th century, in its way a gem, is the structure set up at Athens by Lysicrates, in memory of a choragic victory. This still survives, though the reliefs with which it is adorned have suffered severely from the weather.

The 4th century is the brilliant period of ancient painting. It opens with the painters of the Asiatic school, Zeuxis and Parr hasius and Protogenes, with their contemporaries Nicias and Apollodorus of Athens, Timanthes of Sicyon or Cythnus, and Euphranor of Corinth. It witnesses the rise of a great school at Sicyon, under Eupompus and Pamphilus, which was noted for its scientific character and the fineness of its drawing, and which cul minated in Apelles, the painter of Alexander the Great, and prob ably the greatest master of the art in antiquity. To each of these painters a separate article is given, fixing their place in the history of the art. Of their paintings, unfortunately, but a very inade quate notion can be formed. Vase-paintings, which in the 5th cen fury give us some notion at least of contemporary drawing, are less careful in the 4th century. Now and then are found on them figures admirably designed, or successfully foreshortened ; but these are rare occurrences. The art of the vase decorator has ceased to follow the methods and improvements of contempo rary fresco painters, and is pursued as a mere branch of commerce.

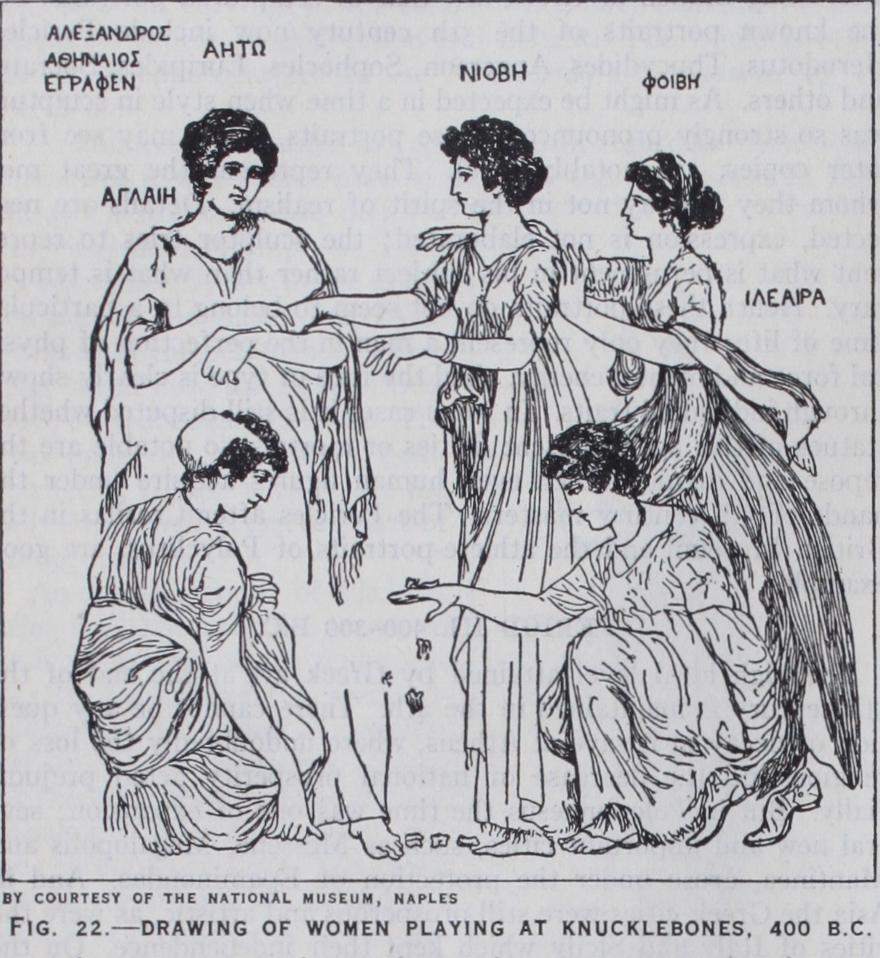

But very few actual paintings of the age survive, and even these fragmentary remains have with time lost the freshness of their colouring; nor are they in any case the work of a noteworthy hand. Our illustration (fig. 22), represents the remains of a drawing on marble, showing a group of women playing knucklebones. It was found at Herculaneum. Though signed by one Alexander of Athens, who was probably a worker of the Roman age, Prof. Robert is right in maintaining that Alexander only copied a design of the age of Zeuxis and Parrhasius. In fact the drawing and grouping is so closely like that of reliefs of about 400 B.C. that the drawing is of great historic value, though there is no colouring. Several other drawings of the same class have been found at Herculaneum, and on the walls of the Transtiberine Villa at Rome (now in the Terme museum).

Praxiteles.—Until about 188o the knowledge of the great Greek sculptors of the 4th century was derived mostly from the statements of ancient writers and from Roman copies, or what were supposed to be copies, of their works, but there is now at least one undoubted original work of Praxiteles as well as sculp tures executed under the immediate direction of, if not from the hand of, other great sculptors of that age—Scopas, Timotheus and others. Among all the discoveries made at Olympia in 1877 none has become so familiar to the artistic world as that of the Hermes of Praxiteles, a first-rate Greek original by one of the greatest of sculptors. Before its discovery almost all the statues in our museums were either late copies of Greek works of art, or else the mere decorative sculpture of temples and tombs, but the Hermes can be submitted to the strictest examination, and it can be seen in every line and touch that there is the work of a great artist. This is more than can be said of any of the literary remains of antiquity—poem, play or oration. Hermes is represented by the sculptor (Pl. VI., fig. 3), in the act of carrying the young child Dionysus to the nymphs who were charged with his rearing. On the journey he pauses and amuses himself by hold ing out to the child-god a bunch of grapes, and watching his eagerness to grasp them. To the modern eye the child is not a success; only the latest art of Greece is at home in dealing with children. But the Hermes, strong without excessive muscular development, and graceful without leanness, is a model of physi cal formation, and his face expresses the perfection of health, natural endowment and sweet nature. The statue can scarcely be called a work of religious art in the modern or Christian sense of the word but from the Greek point of view it is religious, as em bodying the result of the harmonious development of all human faculties and life in accordance with nature.

The Hermes not only added to our knowledge of Praxiteles, but also confirmed the received views in regard to him. Already many works in galleries of sculpture had been identified as copies of statues of his school. Noteworthy among these are, the group at Munich representing Peace nursing the infant Wealth, from an original by Cephisodotus, father of Praxiteles; copies of the Cnidian Aphrodite of Praxiteles, especially one in the Vatican which is here illustrated (Pl. VI., fig. 6), and a torso in the Brit ish Museum (Pl. VI., fig. 5) ; copies of the Apollo slaying a lizard (Sauroctonus), of a Satyr (in the Capitol museum), and others. These works, which are noted for their softness and charm, make understandable the saying of ancient critics that Praxiteles and Scopas were noted for the pathos of their works, as Pheidias and Polyclitus for the ethical quality of those they produced. But the pathos of Praxiteles is of a soft and dreamy character; there is no action, or next to none; and the emotions which he rouses are sentimental rather than passionate. Scopas was of another mood. The discovery Qf the Hermes naturally set archaeologists searching in the museums of Europe for other works, which may from their likeness to it in various respects be set down as Praxitelean in character. In the case- of many of the great sculptors of Greece—Strongylion, Silanion, Calamis and others—it is of little use to search for copies of their works, since there is little trustworthy evidence on which to base our en quiries; but in the case of Praxiteles one really stands on a safe level.

Naturally it is impossible in these pages to give any sketch of the results, some almost certain, some very doubtful, of the re searches of archaeologists in quest of Praxitelean works. But we may mention a few works which have been claimed by good judges as coming from the master himself. Professor Brunn claimed as work of Praxiteles a torso of a satyr in the Louvre, in scheme identical with the well-known satyr of the Capitol. Professor Furtwangler puts in the same category a delicately beautiful head of Aphrodite at Petworth. And his translator, Mrs. Strong, regards the Aberdeen head of a young man in the British Museum as the actual work of Praxiteles. Certainly this last head does not suffer when placed beside the Olympian head of Hermes.

At Mantinea (q.v.) there was found a basis whereon stood a group of Latona and her two children, Apollo and Artemis, made supposedly by Praxiteles. This base bears reliefs representing the musical contest of Apollo and Marsyas, with the Muses as spec tators, reliefs very pleasing in style, and quite in the manner of Attic artists of the 4th century. But of course they cannot be ascribed to the hand of the master himself ; great sculptors did not themselves execute the reliefs which adorned temples and other monuments, hut reserved them for their pupils. Yet the graceful figures of the Muses of Mantinea suggest how much was due to Praxiteles in determining the tone and character of Athenian art in relief in the 4th century. Exactly the same style which marks them belongs also to a mass of sepulchral monuments at Athens, and such works as the Sidonian sarcophagus of the Mourning Women, to be presently mentioned.

Scopas.—Excavation on the site of the temple of Athena Alea at Tegea (q.v.) in 1883 and later resulted in the recovery of works of the school of Scopas. Pausanias tells that Scopas was the architect of the temple, and so important in the case of a Greek temple is the sculptural decoration, that it can scarcely be doubted that the sculpture also of the temple at Tegea was under the supervision of Scopas, especially as he was more noted as a sculp tor than as an architect. In the pediments of tin. temple were represented two scenes from mythology, the hunting of the Caly donian boar and the combat between Achilles and Telephus. To one or other of these scenes belong several heads of local marble discovered on the spot, which are very striking because of their extraordinary life and animation. Unfortunately they are so much injured that they can scarcely be made intelligible except by the help of restoration; one is therefore illustrated, the helmeted head, as restored by a German sculptor (Pl. IV., fig. 3 ; 4) ; its strong bony frame and its depth from front to back are not less note worthy than the parted lips and deeply set and strongly shaded eye ; the latter features impart to the head a vividness of expres sion such as has been found in no previous work of Greek art, but which sets the key to the developments of art which take place in the Hellenistic age. A draped torso of Atalanta from the same pediment has been fitted to one of these heads. Hitherto Scopas was known, setting aside literary records, only as one of the sculptors who had worked at the Mausoleum. Ancient critics and travellers, however, bear ample testimony to his fame, and the wide range of his activity, which extended to northern Greece, Peloponnese and Asia Minor. His Maenads and his Tritons and other beings of the sea were much copied in antiquity. But per haps he reached his highest level in statues such as that of Apollo as leader of the Muses, clad in long drapery ; a head of Apollo found in the Mausoleum, now in the British Museum, is almost certainly a work of Scopas.

Timotheus, Bryaxis, Leochares.—In the interesting precinct of Aesculapius at Epidaurus have been found specimens of the style of an Athenian contemporary of Scopas, who worked with him on the Mausoleum. An inscription which records the sums spent on the temple of the Physician-god, tells that the models for the sculptures of the pediments, and one set of acroteria or roof adornments, were the work of Timotheus. Of the pedimental fig ures and the acroteria considerable fragments have been recov ered, and it may be assumed with confidence that at all events the models for these were by Timotheus. It is strange that the unsat isfactory arrangement whereby a noted sculptor makes models and some local workman the figures enlarged from those models, should have been tolerated by so artistic a people as the Greeks. The subjects of the pediments appear to have been the common ones of battles between Greek and Amazon and between Lapith and Centaur. There are fragments of some of the Amazon figures, one of which striking downwards at the enemy, is here shown (fig. 27). Their attitudes are vigorous and alert ; but the work shows little delicacy of detail. Figures of Nereids riding on horses, which were found on the same site, may very probably be roof orna ments (acroteria) of the temple. There are also several figures of Victory, which probably were acroteria on some smaller temple, perhaps that of Artemis. A base found at Athens, sculptured with figures of horsemen in relief, bears the name of Bryaxis, and was probably made by a pupil of his. Probable conjecture assigns to Leochares the originals copied in the Ganymede of the Vatican, borne aloft by an eagle (P1. IV., fig. 7), and the noble statue of Alexander the Great at Munich (see LEOCHARES). Thus it may fairly be said that students are now acquainted with the work of all the great sculptors who worked on the Mausoleum—Scopas, Bryaxis, Leochares and Timotheus; and are in a far more advan tageous position than were the archaeologists of i 88o for deter mining the artistic problems connected with that noblest of ancient tombs.

The School of Argos and Sicyon.—This was contemporary with the Athenian school of Praxiteles; and of it Lysippus was the most distinguished member. Lysippus continued the academic traditions of Polyclitus, but he was far bolder in his choice of subjects and more innovating in style. Gods, heroes and mortals alike found in him a sculptor who knew how to combine fine ideality with a vigorous actuality. He was at the height of his fame during Alexander's life, and the grandiose ambition of the great Macedonian found him ample employment, especially in the frequent representation of himself and his marshals.

There have been discovered none of the actual works of Lysip pus ; but the best evidence for his style will be found in the statue of Agias, an athlete (P1. VI., fig. I), found at Delphi, and shown by an inscription to be a marble copy of a bronze original by Lysippus. The Apoxyomenus of the Vatican (man scraping himself with a strigil) (P1. VI., fig. 2) has hitherto been regarded as a copy from Lysippus; but of this there is no evidence, and the style of that statue belongs rather to the 3rd century than the 4th. The Agias, on the other hand, is in style contemporary with the works of 4th century sculptors.

Of the elaborate groups of combatants with which Lysippus enriched such centres as Olympia and Delphi, or of the huge bronze statues which he erected in temples and shrines, no ade quate notion can be formed. The recent excavations at Cyrene have produced a figure of Alexander of which the head is of re markable style, and probably Lysippic in type (Pl. VI., fig. 8) ; a pupil of Lysippus, Eutychides, made a very original and charm ing statue of the city of Antioch, seated above the river Orontes. The type was widely copied in later sculpture (Pl. VII., fig. 9).

Many noted extant statues may be attributed with probability to the latter part of the 4th or the earlier part of the 3rd century. The celebrated group at Florence representing Niobe and her chil dren falling before the arrows of Apollo and Artemis is certainly a work of the pathetic school, and may be by a pupil of Praxiteles. Niobe, in an agony of grief, which is in the marble tempered and idealized, tries to protect her youngest daughter from destruction (Pl. VII., fig. I). Whether the group can have originally been fitted into the gable of a temple is a matter of dispute.

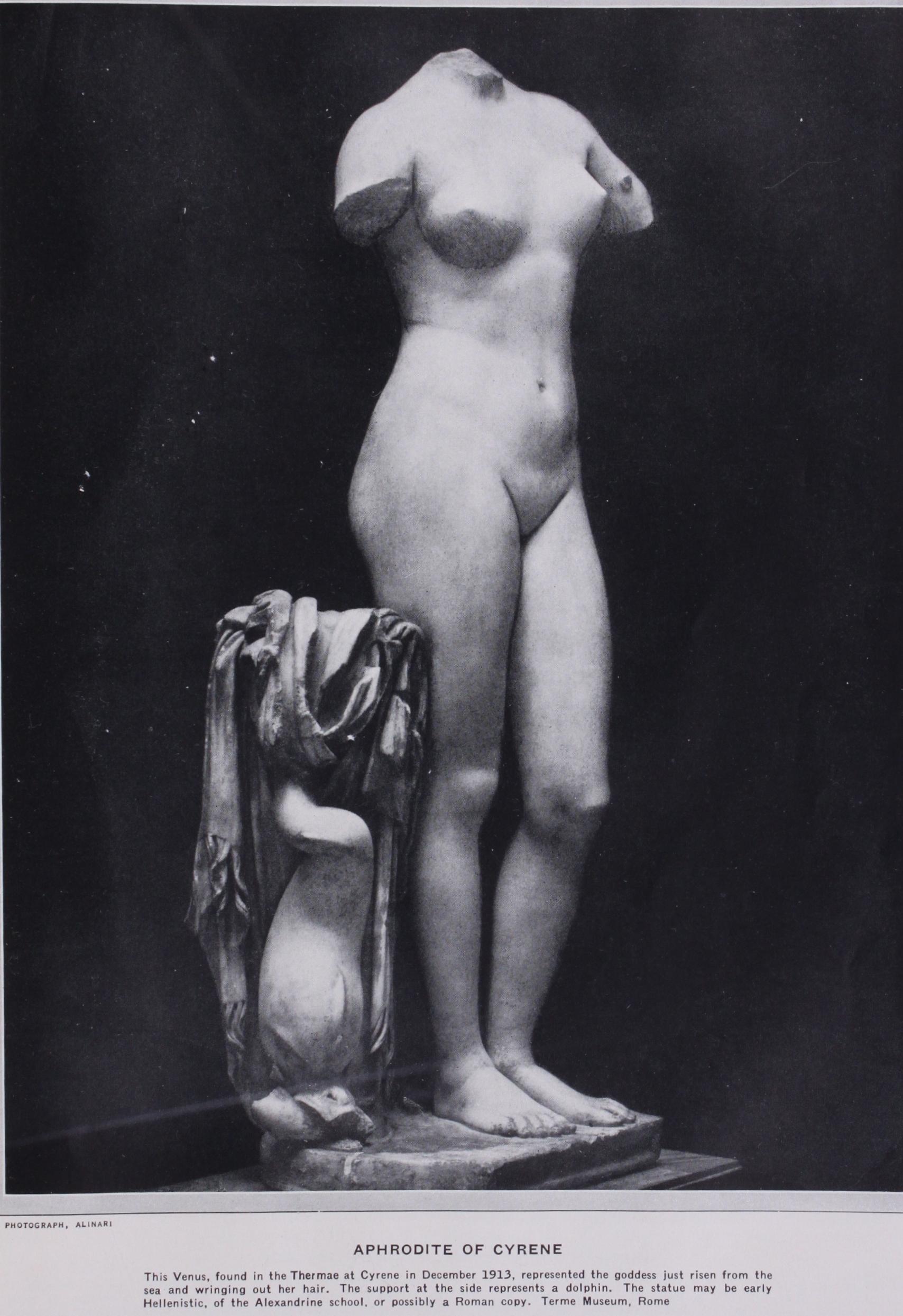

Two great works preserved in the Louvre are so noted that it is but necessary to mention them, the Aphrodite of Melos (Pl. VI., fig. 4), in which archaeologists are now disposed to see the in fluence of Scopas, and the Victory of Samothrace (Pl. VII., fig. a), an original set up by Demetrius Poliorcetes after a naval victory won at Salamis in Cyprus in 3o6 B.C. over the fleet of Ptol emy, king of Egypt.

Nor can two works be passed over without notice so celebrated as the Apollo of the Belvedere in the Vatican (Pl. VI., fig. 7), and the Artemis of Versailles. The Apollo is now by most archaeolo gists regarded as probably a copy of a work of Leochares, to whose Ganymede it bears a superficial resemblance. The Artemis is re garded as possibly due to some artist of the same age. But it is by no means clear that either of these figures can be removed from among the statues of the Hellenistic age. The old theory of Preller, which saw in them copies from a trophy set up to com memorate the repulse of the Gauls at Delphi in 278 B.C., has not lost its plausibility.

Sarcophagi of Sidon.