The Growth of the Greek States

THE GROWTH OF THE GREEK STATES The Greek world at the beginning of the 6th century B.C. pre sents a picture in many respects different from that of the Ho meric Age. The Greek race is no longer confined to the Greek peninsula. It occupies the islands of the Aegean, the western seaboard of Asia Minor, the coasts of Macedonia and Thrace, of southern Italy and Sicily. Scattered settlements are found as far apart as the mouth of the Rhone, the north of Africa, the Crimea and the eastern end of the Black Sea. The Greeks are called by a national name, Hellenes, the symbol of a fully-developed na tional self-consciousness. They are divided into three great branches, the Dorian, the Ionian, and the Aeolian, names almost, or entirely unknown to Homer. The heroic monarchy has nearly everywhere disappeared. In Greece proper, south of Thermopylae, it survives, but in a peculiar form, in the Spartan state alone. What is the significance and the explanation of contrasts so profound ? Dorian Invasion.—It is probable that the explanation is to be found, directly or indirectly, in a single cause, the Dorian inva sion. In Homer the Dorians are mentioned in one passage only (Odyssey xix. 177). They there appear as one of the races which inhabit Crete. In the historical period the whole Peloponnese, with the exception of Arcadia, Elis and Achaea, is Dorian. In northern Greece the Dorians occupy the little state of Doris, and in the Aegean they form the population of Crete, Rhodes and some smaller islands. Thus the chief centres of Minoan and Mycenaean culture have passed into Dorian hands, and the chief seats of Achaean power are included in Dorian states. Greek tradition explained the overthrow of the Achaean system by an invasion of the Peloponnese by the Dorians, a northern tribe, which had found a temporary home in Doris. The story ran that, after an unsuccessful attempt to force an entrance by the Isthmus of Corinth, they had crossed from Naupactus, at the mouth of the Corinthian Gulf, landed on the opposite shore, and made their way into the heart of the Peloponnese, where a single victory gave them possession of the Achaean states. Their con quests were divided among the invaders into three shares, for which lots were cast, and thus the three states of Argos, Sparta and Messenia were created. Much in this tradition is impossible or improbable. It is improbable that the conquest should have been either as sudden, or as complete, as the legend represents. But there are indications that the conquest was gradual, and that the displacement of the older population was incomplete. The improbability of the details affords, however, no ground for questioning the reality of the invasion. The tradition can be traced back at Sparta to the 7th century B.C. (Tyrtaeus, quoted by Strabo, p. 362), and there is abundant evidence, other than that of legend, to corroborate it. There is the Dorian name, to begin with. If it originated on the coast of Asia Minor, where it served to distinguish the settlers in Rhodes and the neighbour ing islands from the Ionians and Aeolians to the north of them, how came the great and famous states of the Peloponnese to adopt a name in use among the petty colonies planted by their kinsmen across the sea? Or, if Dorian is simply Old Pelopon nesian, how are we to account for the Doric dialect or the Dorian pride of race? There are great differences between the literary Doric, the dialect of Corinth and Argos, and the dialects of Laconia and Crete; there are affinities between the dialect of Laconia and the non-Dorian dialects of Arcadia and Elis. But all the Doric dialects are distinguished from all other Greek dialects by certain common characteristics. Perhaps the strongest sentiment in the Dorian nature is the pride of race. Indeed, it looks as if the Dorians claimed to be the sole genuine Hellenes. How can we account for an indigenous population, first imagining itself to be immi grant, and then developing a contempt for the rest of the race, equally indigenous with itself, on account of a fictitious differ ence in origin? Finally, there is the archaeological evidence. The older civilization comes to an abrupt end, on the mainland at least, at the very period to which tradition assigns the Dorian migration. Its development is greatest, and its overthrow most complete, precisely in the regions occupied by the Dorians and the other tribes, whose migrations were traditionally connected with theirs. It is hardly too much to say that the archaeologist would have been compelled to postulate an inroad into central and southern Greece of tribes from the north, at a lower level of culture, in the course of the 12th and i i th centuries B.C., if the historian had not been able to direct him to the traditions of the great migrations (metanastaseis), of which the Dorian inva sion was the chief.

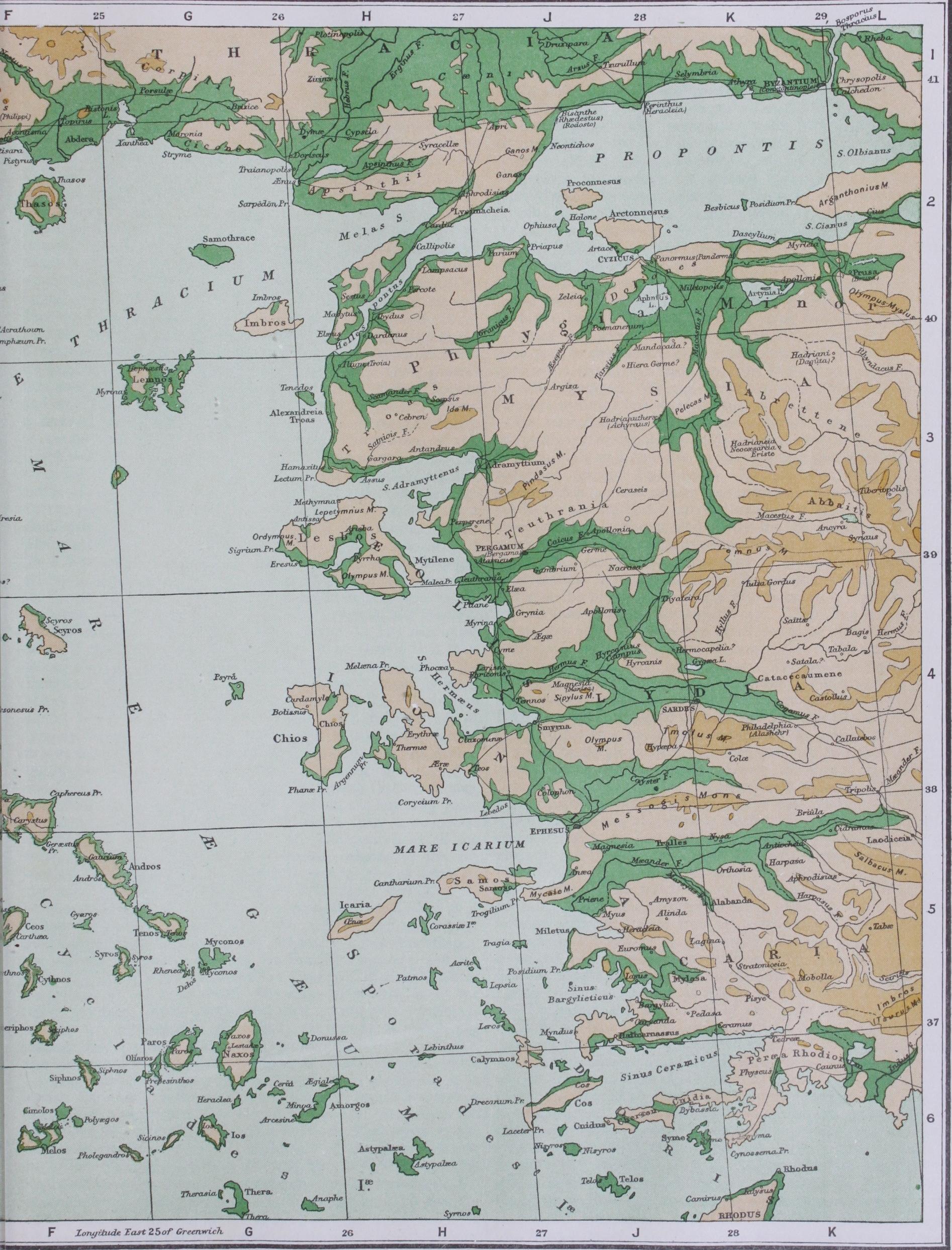

With the Dorian migration Greek tradition connected the ex pansion of the Greek race eastwards across the Aegean. In the historical period the Greek settlements on the western coast of Asia Minor fall into three clearly defined groups. To the north is the Aeolic group, consisting of the island of Lesbos and twelve towns, mostly insignificant, on the opposite mainland. To the south is the Dorian hexapolis, consisting of Cnidus and Halicar nassus on the mainland, and the islands of Rhodes and Cos. In the centre comes the Ionian dodecapolis, a group consisting of ten towns on the mainland, together with the islands of Samos and Chios. Of these Greek settlements the Ionian is incomparably the most important. The Ionians also occupy Euboea and the Cyclades. Although Cyprus (and possibly Pamphylia) had been occupied by settlers from Greece in the Mycenaean age, Greek tradition puts the colonization of Asia Minor and the islands of the Aegean after the Dorian migration. Both the Homeric and the archaeological evidence seem to point to the same conclusion. Between Rhodes on the south and the Troad on the north scarcely any Mycenaean remains have been found. Homer is ignorant of any Greeks east of Euboea. If the poems are earlier than the Dorian invasion his silence is conclusive. If the poems are some centuries later than the invasion, they at least prove that, within a few generations of that event, it was the belief of the Greeks of Asia Minor that their ancestors had crossed the seas after the close of the Heroic Age. It is probable, too, that the names Ionian and Aeolian, the former of which is found once in Homer, and the latter not at all, originated among the colonists in Asia Minor, and served to designate first the members of the Ionic and Aeolic dodecapoleis. The only Ionia known to history is in Asia Minor. It does not follow that Ionia is the original home of the Ionian race. It almost certainly follows, however, that it is the original home of the Ionian name.

Hellenes.

It is less easy to account for the name Hellenes. The Greeks were profoundly conscious of their common nation ality, and of the gulf that separated them from the res` of man kind. They themselves recognized a common race and language, and a common type of religion and culture, as the chief factors in this sentiment of nationality (see Herod. viii. 144). "Hellenes" . was the name of their common race, and "Hellas" of their com mon country. In Homer there is no distinct consciousness of a common nationality, and consequently no antithesis of Greek and Barbarian (see Thuc. i. 3). Nor is there a true collective name. There are indeed Hellenes (though the name occurs in one passage only, Iliad ii. 684) and there is a Hellas; but Homer's Hellas, whatever its precise signification may be, is, at any rate, not equivalent either to Greece proper or to the land of the Greeks; his Hellenes are the inhabitants of a small district to the south of Thessaly. It is possible that the diffusion of the Hellenic name • was due to the Dorian invaders. Its use can be traced back to the first half of the 7th century. • Monarchy and Oligarchy.—Not less obscure are the causes of the f all of monarchy. It cannot have been the immediate effect of the Dorian conquest, for the states founded by the Dorians were at first monarchically governed. It may, however, have been an indirect effect of it. The power of the Homeric kings is more limited than that of the rulers of Cnossus, Tiryns or Mycenae. In other words, monarchy is already in decay at the epoch of the invasion. The invasion, in its effects on wealth, commerce and civilization, is almost comparable to the irruption of the bar barians into the Roman empire. The monarch of the Minoan and Mycenaean Age has extensive revenues at his command ; the monarch of the early Dorian states is little better than a petty chief. Thus the interval, once a wide one, that separates him from the nobles, tends to disappear. The decay of monarchy was grad ual; much more gradual than is generally recognized. There were parts of the Greek world in which it still survived in the 6th century, e.g., Sparta, Cyrene, Cyprus, and possibly Argos and Tarentum. Both Herodotus and Thucydides apply the title "king' (basileus) to the rulers of Thessaly in the 5th century. The date at which monarchy gave place to a republican form of government must have differed, and differed widely, in different cases. The traditions relating to the foundation of Cyrene assume the exist ence of monarchy in Thera and in Crete in the middle of the 7th century (Herod. iv. i 5o and 154), and the reign of Amphicrates at Samos (Herod. iii. S9) can hardly be placed more than a gen eration earlier. In view of our general ignorance of the history of the 7th and 8th centuries, it is hazardous to pronounce these instances exceptional. On the other hand, the change from monarchy to oligarchy was completed at Athens before the end of the 8th century, and at a still earlier date in some of the other states. The process, again, by which the change was effected was, in all probability, less uniform than is generally assumed. There are very few cases in which we have any trustworthy evidence, and the instances about which we are informed refuse to be re duced to any common type. In Greece proper our information is fullest in the case of Athens and Argos. In the former case, the king is gradually stripped of his powers by a process of devolu tion. In place of an hereditary king, ruling for life, we find three annual and elective magistrates, between whom are divided the executive, military, and religious functions of the monarch (see ARCHON) . At Argos the fall of the monarchy is preceded by an aggrandisement of the royal prerogatives. There is nothing in common between these two cases, and there is no reason to sup pose that the process elsewhere was analogous to that at Athens. Everywhere, however, oligarchy is the form of government which succeeds to monarchy. Political power is monopolized by a class of nobles, whose claim to govern is based upon birth and the pos session of land, the most valuable form of property in an early society. Sometimes power is confined to a single clan (e.g., the Bacchiadae at Corinth) ; more commonly, as at Athens, all houses that are noble are equally privileged. In every case there is found, as the adviser of the executive, a boule, or council, representa tive of the privileged class. Without such a council a Greek oligarchy is inconceivable. The relations of the executive to the council doubtless varied. At Athens the real authority was exer cised by the archonsl ; in many states the magistrates were prob ably subordinate to the council (cf. the relation of the consuls to the senate at Rome). And the way in which the oligarchies used their power varied also. The cases in which the power was abused are naturally the ones of which we hear, for an abuse of power gave rise to discontent and was the ultimate cause of revolution. We hear little or nothing of the cases in which power was exer cised wisely. Happy is the constitution which has no annals! Oligarchy held its ground for generations, or even for centuries in a large proportion of the Greek states; and a government which, like the oligarchies of Elis, Thebes or Aegina, could maintain itself for three or four centuries cannot have been merely oppressive.

Trade.

The period of the transition from monarchy to oli garchy is the period in which commerce begins, to develop and trade routes to be organized. Greece had been the centre of an active trade in the Minoan and Mycenaean epochs. The products of Crete and of the Peloponnese had found their way to Egypt and Asia Minor. The overthrow of the older civilization put an end to commerce. The seas became insecure and intercourse with the East was interrupted. Our earliest glimpses of the Aegean after the period of the migrations disclose the raids of the pirate and the activity of the Phoenician trader. With the 8th century trade begins to revive, and the Phoenician retires before his Greek competitor. For some time to come, however, no clear distinction is drawn between the trader and the pirate. The pioneers of Greek trade in the West are the pirates of Cumae (Thuc. vi. 4). The rapid development of Greek commerce in the 7th and 6th cen turies must have been assisted by the great discovery of the early part of the former century, the invention of coined money.IIf the account of early Athenian constitutional history given in the Athenaion Politeia were accepted, it would follow that the archons were inferior in authority to the Eupatrid Boule, the Areopagus.

To the Lydians, rather than the Greeks, belongs the credit of the discovery ; but it was the genius of the latter race that divined the importance of the invention and spread its use. The coinage of the Ionian towns goes back to the reign of Gyges (c. 675 B.c.). And in Ionia commercial development is earliest and greatest. In the most distant regions the Ionian is first in the field. Egypt and the Black Sea are both opened up to Greek trade by Miletus, the Adriatic and the Western Mediterranean by Phocaea and Samos. Of the twelve states engaged in the Egyptian trade in the 6th century all, with the exception of Aegina, are from the eastern side of the Aegean (Herod. ii. 178). On the western side the chief centres of trade during these centuries were the islands of Euboea and Aegina and the town of Corinth. The Aeginetan are the earliest coins of Greece proper (c. 65o B.c.); and the two rival scales of weights and measures, in use amongst the Greeks of every age, are the Aeginetan and the Euboic. Commerce natur ally gave rise to commercial leagues, and commercial relations tended to bring about political alliances. Foreign policy even at this early epoch seems to have been largely determined by con siderations of commerce. Two leagues, the members of which were connected by political as well as commercial ties, can be rec ognized. At the head of each stood one of the two rival powers in the island of Euboea, Chalcis and Eretria. Their primary ob ject was doubtless protection from the pirate and the foreigner. Competing routes were organized at an early date under their influence, and their trading connections can be traced from the heart of Asia Minor to the north of Italy. Miletus, Sybaris and Etruria were members of the Eretrian league ; Samos, Corinth, Rhegium, Zancle (commanding the Straits of Messina), and Cumae, on the Bay of Naples, of the Chalcidian. The wool of the Phrygian uplands, woven in the looms of Miletus, reached the Etruscan markets by way of Sybaris; through Cumae, Rome and the rest of Latium obtained the elements of Greek culture. Greek trade, however, was confined to the Mediterranean area. The Phoenician and the Carthaginian navigators penetrated to Britain; they discovered the passage round the Cape two thousand years before Vasco da Gama's time. The Greek sailor dared not adven ture himself outside the Black Sea, the Adriatic and the Mediter ranean. Greek trade, too, was essentially maritime. Ports visited by Greek vessels were often the starting-points of trade routes into the interior; the traffic along those routes was left in the hands of the natives (see, e.g., Herod. iv. 24). Geography is the in vention of the Greeks. The first maps were made by them (in the 6th century) ; and it was the discoveries and surveys of their sailors that made map-making possible.

Colonization.

The period of colonization, in its narrower sense, extends from the middle of the 8th to the middle of the 6th century. Greek colonization is, however, merely a continua tion of the process which at an earlier epoch had led to the settle ment, first of Cyprus, and then of the islands and coasts of the Aegean. From the earlier settlements the colonization of the historical period is distinguished by three characteristics. The later colony acknowledges a definite metropolis ("mother-city") ; it is planted by a definite oecist (oikistes) ; it has a definite date assigned to its foundation'. It would be a mistake to regard Greek colonization as commercial in origin, in the sense that the colonies were in all cases established as trading-posts. This was the case with the Phoenician and Carthaginian settlements, most of which remained mere factories; and some of the Greek colonies (e.g., many of those planted by Miletus on the shores of the Black Sea) bore this character. The typical Greek colony, however, was neither in origin nor in development a mere trading-post. It was, or it became, a polis, a city-state, in which was reproduced the life of the parent state. Nor was Greek colonization, like the emigration from Europe to America and Australia in the igth century, simply the result of over-population. The causes were as various as those which can be traced in the history of modern colonization. Those which were established for the purposes of trade may be compared to the factories of the Portuguese and 'The dates before the middle of the 7th century are in most cases artificial, e.g., those given by Thucydides (book vi.) for the earlier Sicilian settlements. See J. P. Mahaffy, Journal of Hellenic Studies, ii. 564 ff.Dutch in Africa and the Far East. Others were the result of political discontent, in some form or shape ; these may be com pared to the Puritan settlements in New England. Others again were due to ambition or the mere love of adventure (see Herod. v. 42, et seq., the career of Dorieus). But however various the causes, two conditions must always be presupposed—an expan sion of commerce and a growth of population. Within the narrow limits of the city-state there was a constant tendency for popula tion to become redundant until, as in the later centuries of Greek life, its growth was artificially restricted. Alike from the Roman colonies, and from those founded by the European nations in the course of the last few centuries, the Greek colonies are distin guished by a fundamental contrast. It is significant that the contrast is a political one. The Roman colony was in a position of entire subordination to the Roman state, of which it formed a part. The modern colony was, in varying degrees, in political sub jection to the home government. The Greek colony was com pletely independent from the first. The ties that united a colony to its metropolis were those of sentiment and interest ; the political tie did not exist. There were exceptions. The colonies established by imperial Athens closely resembled the colonies of imperial Rome. The cleruchy (q.v.) formed part of the Athenian state, the cleruchs kept their status as citizens of Athens and acted as a military garrison. And if the political tie, in the proper sense, was wanting, political relations sprang out of commercial or senti mental ones. Thus Corinth interfered twice to save her colony Syracuse from destruction, and Megara brought about the revolt of Byzantium, her colony, from Athens. Sometimes it is not easy to distinguish political relations from a political tie (e.g., the rela tions of Corinth, both in the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, to Ambracia and the neighbouring group of colonies). When we compare the development of the Greek and the modern colonies we shall find that the development of the former was even more rapid than that of the latter. The differences of race, of colour and of climate, with which the chief problems of modern colonization are connected, played no part in the history of the Greek settle ments. The races amongst whom the Greeks planted themselves were in some cases on a similar level of culture. Where the na tives were still backward or barbarous, they came of a stock either closely related to the Greek, or at least separated from it by no great physical differences. Amalgamation with the native races was easy, and it involved neither physical nor intellectual degeneracy as its consequence. Of the races with which the Greeks came in contact the Thracian was far from the highest in the scale of culture; yet two of the greatest names in the Great Age of Athens are those of men who had Thracian blood in their veins, Cimon and the historian Thucydides. In the absence of any distinction of colour. no insuperable barrier existed between the Greek and the hellenized native. The demos of the colonial cities was largely recruited from the native population', nor was there anything in the Greek world analogous to the "poor whites" or the "black belt." Of hardly less importance were the climatic conditions. In this respect the Mediterranean area is unique. There is no other region of the world of equal extent in which these conditions are at once so uniform and so favourable. No where had the Greek settler to encounter a climate which was either unsuited to his labour or subversive of his vigour. That in spite of these advantages so little, comparatively speaking, was effected in the work of hellenization before the epoch of Alexan der and the Diadochi, was the effect of a single counteracting cause. The Greek colonist, like the Greek trader, clung to the shore. He penetrated no farther inland than the sea-breeze. Hence it was only in islands, such as Sicily or Cyprus, that the process of hellenization was complete.

The Tyrants.

To the 7th century belongs another movement of high importance in its bearing upon the economic, religious and literary development of Greece, as well as upon its constitutional history. This movement is the rise of the "tyrannis." In the political writers of a later age the word possesses a clear-cut connotation. From other forms of monarchy it is distinguished 'At Syracuse the demos makes common cause with the Sicel serf population against the nobles (Herod. vii. 155) by a twofold differentiation. The turannos is an unconstitutional ruler, and his authority is exercised over unwilling subjects. In the 7th and 6th centuries the line was not drawn so distinctly between the tyrant and the legitimate monarch. Even Herodotus uses the words "tyrant" and "king" interchangeably (e.g., the princes of Cyprus are called "kings" in v. r i o and "tyrants" in v. 1o9), so that it is sometimes difficult to decide whether a legitimate monarch or a tyrant is meant (e.g., Aristophilides of Tarentum, iii. 136, or Telys of Sybaris, v. 44). But the distinction between the tyrant and the king of the Heroic Age is a valid one. It is not true that his rule was always exercised over unwilling subjects; it is true that his position was always unconstitutional. The Homeric king is a legitimate monarch ; his authority is in vested with the sanctions of religion and immemorial custom. The tyrant is an illegitimate ruler; his authority is not recognized, either by customary usage or by express enactment. But the word "tyrant" was originally a neutral term ; it did not necessarily imply a misuse of power. The origin of the tyrannis is obscure. The word turannos has been thought, with some reason, to be Lydian. Probably both the name and the thing originated in the Greek colonies of Asia Minor, though the earliest tyrants of whom we hear in Asia Minor (at Ephesus and Miletus) are a genera tion later than the earliest in Greece itself, where, both at Sicyon and at Corinth, tyranny appears to date back to the second quarter of the 7th century. It is not unusual to regard tyranny as a universal stage in the constitutional development of the Greek states and as a stage that occurs everywhere at one and the same period. In reality, tyranny is confined to certain regions, and is not a phenomenon peculiar to any one age or century. In Greece proper, before the 4th century B.C., it is confined to a small group of states round the Corinthian and Saronic Gulfs. The greater part of the Peloponnese was exempt from it, and there is no good evidence for its existence north of the Isthmus, except at Megara and Athens. It plays no part in the history of the Greek cities in Chalcidice and Thrace. It was rare in the Cyclades. The regions in which it finds a congenial soil are two, Asia Minor and Sicily. Thus it is incorrect to say that most Greek states passed through this stage, or to assume that they passed through it at the same time. There is no "Age of the Tyrants." Tyranny began in the Peloponnese a hundred years before it appears in Sicily, and disappeared in the Peloponnese almost before it began in Sicily. In the latter the great age of tyranny comes at the beginning of the 5th century; in the former it is at the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 6th. At Athens the history of tyranny begins after it has ended both at Sicyon and Corinth. There is, indeed, a period in which tyranny is non existent in the Greek states ; roughly speaking, the last sixty years of the 5th century. But with this exception, there is no period in which the tyrant is not to be found. The greatest of all the tyrannies, that of Dionysius at Syracuse, belongs to the 4th century. Nor must it be assumed that tyranny always comes at the same stage in the history of a constitution; that it is al ways a stage between oligarchy and democracy. At Corinth it is followed by oligarchy, that lasts, with a brief interruption, for two hundred and fifty years. At Athens it is not immediately preceded by oligarchy. Between the Eupatrid oligarchy and the rule of Peisistratus there comes the timocracy of Solon. These exceptions do not stand alone. The cause of tyranny is, in one sense, uniform. In the earlier centuries, at any rate, tyranny is always the expression of discontent ; the tyrant is always the champion of a cause. But it would be a mistake to suppose that the discontent is necessarily political, or that the cause which he champions is always a constitutional one. At Sicyon it is racial. Cleisthenes is the champion of the older population against their Dorian oppressors (see Herod. v. 67, 68). At Athens the discontent is economic rather than political; I isistratus is the champion of the Diacrii, the inhabitants of the poorest region of Attica. The party strifes in the early history of Miletus, which doubtless gave the tyrant his opportunity, are concerned with the claims of rival industrial classes. In Sicily the tyrant is the ally of the rich and the foe of the demos, and the cause which he champions, both in the 5th century and the 4th, is a national one, that of the Greek against the Carthaginian. We may suspect that in Greece itself the tyrannies of the 7th century are the expression of an anti-Dorian reaction. It can hardly be an accident that the states in which the tyrannis is found at this epoch, Corinth, Megara, Sicyon, Epidaurus, are all of them states in which a Dorian upper class ruled over a subject population. In Asia Minor the tyrannis assumes a peculiar character after the Persian conquest. The tyrant rules as the deputy of the Persian satrap. Thus in the East the tyrant is the enemy of the national cause; in the West, in Sicily, he is its champion.

Tyranny has analogies in Roman history, in the power of Caesar, or of the Caesars ; in the despotisms of mediaeval Italy; or even in the Napoleonic empire. Between the tyrant and the Italian despot there is indeed a real analogy; but between the Roman principate and the Greek tyrannis there are two essential differences. In the first place, the principate was expressed in constitutional forms, or veiled under constitutional fictions; the tyrant stood altogether outside the constitution. And, secondly, at Rome both Julius and Augustus owed their position to the power of the sword. The power of the sword, it is true, plays a large part in the history of the later tyrants (e.g., Dionysius of Syracuse) ; the earlier ones, however, had no mercenary armies at their command. We can hardly compare the bodyguard of Peisistratus to the legions of the first or the second Caesar.

The view taken of the tyrannis in Greek literature is almost uniformly unfavourable. In this respect there is no difference between Plato and Aristotle, or between Herodotus and the later historians (except Thucydides). His policy is represented as purely selfish, and his rule as oppressive. Herodotus is influenced partly by the traditions current among the oligarchs, who had been the chief sufferers, and partly by the odious associations which had gathered round tyranny in Asia Minor. The philoso phers write under their impressions of the later tyrannis, and their account is largely a priori. We seldom find any attempt, either in the philosophers or the historians, to do justice to the real services rendered by the tyrants. Their first service was constitutional. They helped to break down the power of the old aristocratic houses, and thus to create the social and political conditions indispensable to democracy. The tyrannis involved the sacrifice of liberty in the cause of equality. When tyranny falls, it is never succeeded by the aristocracies which it has overthrown. It is frequently succeeded by an oligarchy, in which the claim to exclusive power is based upon wealth, or the possession of land. It would be unfair to treat this service as one that was rendered unconsciously and unwillingly. Where the tyrant asserted the claims of an oppressed class, he consciously aimed at the destruc tion of privilege and the effacement of class distinctions. Hence it is unjust to treat his power as resting upon mere force. A gov ernment which can last eighty or a hundred years, as was the case with the tyrannies at Corinth and Sicyon, must have a moral force behind it. It must rest upon the consent of its subjects. The second service which the tyrants rendered to Greece was political. Their policy tended to break down the barriers which isolated each petty state from its neighbours. In their history we can trace a system of widespread alliances, which are often cemented by matrimonial connections. The Cypselid tyrants of Corinth appear to have been allied with the royal families of Egypt, Lydia and Phrygia, as well as with the tyrants of Miletus and Epidaurus, and with some of the great Athenian families. In Sicily we find a league of the northern tyrants opposed to a league of the southern; and in each case there is a corresponding matrimonial alliance. Anaxilaus of Rhegium is the son-in-law and ally of Terillus of Himera ; Gelon of Syracuse stands in the same relation to Theron of Agrigentum. Royal marriages have played a great part in the politics of Europe. In the comparison of Greek and modern history it has been too often forgotten how great a difference it makes, and how great a disadvantage it involves, to a republic that it has neither sons nor daughters to give in marriage. In commerce and colonization the tyrants con tinued the work of the oligarchies to which they succeeded. Greek trade owed its expansion to the intelligent efforts of the oligarchs who ruled at Miletus and Corinth, in Samos, Aegina and Euboea; but in Miletus, Corinth, Sicyon and Athens, there was a further development, and a still more rapid growth, under the tyrants. In the same way, the foundation of the colonies was in most cases due to the policy of the oligarchical governments. They can claim credit for the colonies of Chalcis and Eretria, of Megara, Phocaea and Samos, as well as for the great Achaean settlements in south ern Italy. The Cypselids at Corinth, and Thrasybulus at Miletus, are instances of tyrants who colonized on a great scale.

Religion under the Tyrants.

In their religious policy the tyrants went far to democratize Greek religion. The functions of monarchy had been largely religious; but, while the king was necessarily a priest, he was not the only priest in the community. There were special priesthoods, hereditary in particular families, even in the monarchial period; and upon the fall of the monarchy, while the priestly functions of the kings passed to republican magistrates, the priesthoods which were in the exclusive possession of the great families tended to become the important ones. Thus, before the rise of tyranny, Greek religion is aristocratic. The cults recognized by the state are the sacra of noble clans. The re ligious prerogatives of the nobles helped to confirm their political ones, and, as long as religion retained its aristocratic character, it was impossible for democracy to take root. The policy of the tyrants aimed at fostering popular cults which had no associations with the old families, and at establishing new festivals. The cult of the wine-god, Dionysus, was thus fostered at Sicyon by Cleis thenes, and at Corinth by the Cypselids ; while at Athens a new festival of this deity, which so completely overshadowed the older festival that it became known as the Great Dionysia, probably owed its institution to Peisistratus. Another festival, the Pan athenaea, which had been instituted only a few years before his rise to power, became under his rule, and thanks to his policy, the chief national festival of the Athenian state. Everywhere we find the tyrants the patrons of literature. Pindar and Bacchylides, Aeschylus and Simonides found a welcome at the court of Hieron. Polycrates was the patron of Anacreon, Periander of Arion. To Peisistratus has been attributed the first critical edition of the text of Homer, a work as important in the literary history of Greece as was the issue of the Authorized Version of the Bible in English history. To judge fairly of tyranny and of its contribu tions to the development of Greece, we must remember the states in whose history the period of greatest power coincides with the rule of a tyrant, such as Corinth and Sicyon, Syracuse in the 5th, and again in the 4th century ; and probably Samos and Miletus. In the case of Athens the splendour of the Great Age blinds us to the greatness of the results achieved by the policy of the Peisistratids.