Western Asiatic Architecture Architectural Articles

WESTERN ASIATIC ARCHITECTURE; ARCHITECTURAL ARTICLES, etc.). However, for moulding their supports they chose con ventional rather than naturalistic forms, therein resembling their Aegean predeces sors; particularly Greek was the patient genius with which they perfected every ele ment, rarely deviating from the forward path to invent new forms or new solutions of old problems. This conservative adhe rence to older types led to such master pieces as the Parthenon and Erechtheum.

Primitive Period (1100-600 B.C.) .

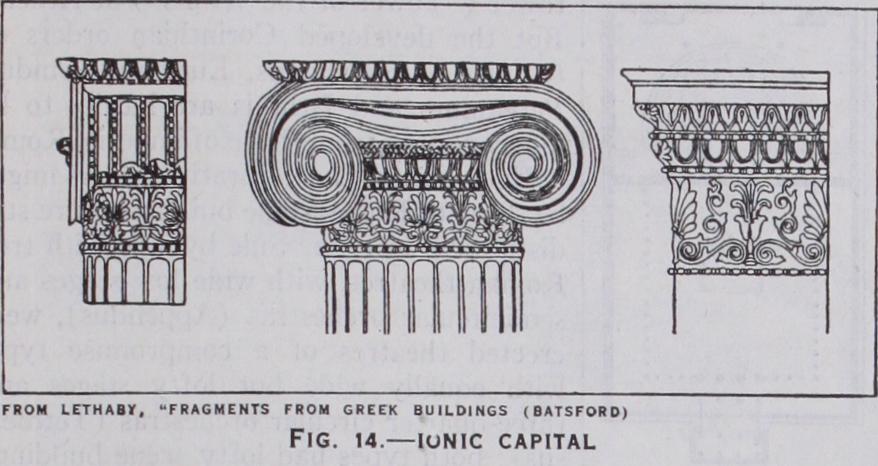

While Greek domestic architecture began with the Dorian invasion, monumental religious architecture first appeared in the 9th century. Mere open areas with altars (Aegina, Sparta, Ephesus) no longer sufficed when gods were represented in large images, requiring special temples. The houses of men furnished the patterns : from the circular nomadic hut developed the horseshoe or apsidal plan (Eretria, Gonnoi), the oblong plan with curved walls (Thermon), and eventually the normal straight-sided oblong, the axis running east-and-west, and the entrance always at one end. A porch (pronaos) might be added in front, a sanctuary (adytum) at the rear. Walls were of mud-brick resting on stone socles, their free ends (antae and door jambs) encased in wooden sheathing. Simul taneously the roof developed from the no madic thatched beehive, through the long ogival mud-brick vault, to the sloping hipped roof with wooden rafters, supported by girders resting on the side walls.In wider temples these cross girders had to be reinforced by columnsplaced in single file along the main axis (Selinus, Prinias, Locri, Sparta, Neandria, Samos) . Thus came into Greek architecture the character istic post-and-lintel system. At first mere wooden posts, these internal supports were gradually moulded on opposite sides of the Aegean sea into two different types. Proto-Doric and Proto-Ionic. The former, with its circular moulded capital and square abacus, was copied in wood from such surviving Aegean works as the Lion Gate at Mycenae. The Proto-Ionic type originated as an elongated capital, early transformed into stone ; slender unfluted shafts (sometimes with special bases) were capped by garlands of drooping leaves from which spring vertical volutes (Lesbos, Neandria, Larissa), an Egyptian motive transmitted by Phoenicians and Hittites.

In an open pronaos, a central column repeated the axial colon nade (Locri, Prinias) ; next, because central columns obscured the cult image, the axis was opened by using two internal colonnades and so two columns in-antis on the front. Thus the column first appeared on the exterior and introduced a new problem, the crea tion of an entablature. The transverse girder formed the archi trave, a single solid beam in the Doric, compounded of superposed planks (fascias) in the Ionic; upon this rested the ends of ceiling beams, heavy and widely spaced (triglyphs) in the Doric, light and closely spaced (dentils) in the Ionic.

Mutular eaves formed by overhanging raft ers characterized the Doric cornice; the Ionic was merely hollowed to shed rain water. The light wooden Ionic entablature is best known through imitations in native rock-cut tombs of Asia Minor; the Doric forms are revealed through the survival of terracottas which protected the bulky timbers, black or blue triglyphs casing the fibrous ends of ceiling beams, gaily painted terracotta metopes occupying the interstices, and facings with conventional patterns on the cornice. The ridge of the hipped roof was soon prolonged to the front, forming a gable (pediment), the rear end sometimes remaining hipped (Thermon, Sparta). The gutter (sima) which had hitherto crowned the cor nice on all four sides was only momentarily retained under the ped iment (Syracuse, Geloan treasury at Olympia) ; but the mutules, equally anachronistic symbols of rafters under a pediment, re mained even on the facade. Semicircular terracotta tiles covered the joints between the concave pan tiles, terminating at the eaves in semicircular antefixes.

While the Ionians limited themselves to the pronaos in-antis, the emergence of the column and the development of the order inspired Dorian architects to further embellishments. The pronaos might be repeated in a rear porch (opisthodomus), or the whole temple surrounded by a peristyle. From the five lines of the flank walls and the axial and flank colonnades resulted pentastyle facades (Thermon), two internal colonnades required hexastyle facades (Heraeum at Olympia) ; the flanks were long in pro portion, with 15 or 16 columns. The height of the wooden columns, II- axial spacings (Olympian Heraeum) each of 4i diameters (Argive Heraeum), seems to have been 7 diameters; the entab lature was about two-fifths of the column height.

Archaic Period (600-500 B.C.).

The new-rich western colonies transformed the peripteral temple into limestone ; the Ionian East soon followed with the greater splendour of marble. But the motherland of Hellas remained conservative; during eight centuries the columns of the Olympian Heraeum were gradually replaced in stone ; as late as 513 B.C. marble was limited to one ostentatious temple facade (Delphi). Limestone, however, was coated with fine marble stucco; sandstone was often used in the West for carved members ; terracotta cornice revetments were gradually eliminated and the terracotta gutters and even roof tiles replaced in more important temples by marble.A few primitive types of plans survived, either apsidal (Delphi, Athens, Corinth, Olympia) or with axial colonnades (Olympia, Delos, Paestum, Metapontum) . The sim ple diastyle in-antis plan long prevailed in Hellas; at Athens a double temple had porches at both ends. But the most fa voured temple plan was the hexastyle per ipteral, sometimes (in Sicily) with the facade doubled for greater magnificence.

The opisthodomus (rear porch) was cus tomary in Hellas, the closed adytum (se cret chamber) in the West ; the interior might have two rows of columns (in Hellas) or none at all (in Sicily). The East outdid the West by doubling the colonnade on all sides, giving the octastyle dipteral plan (Ephesus, Samos, Mag nesia), imitated also at Athens (Olympeium) ; at Corcyra and Selinus ("GT") the inner lines of columns were omitted, becom ing pseudodipteral; at Acragas (Olympeium), while retain ing the same vast total dimensions as at Selinus, the number of columns was reduced and the scale thereby so enlarged that the intervals were filled with walls, becoming pseudoperip teral. The employment of colossal dimensions, with stylobates measuring up to 18o X 365 ft., column diameters up to 14 f t. (Acragas), column spacings up to 284 ft. (Ephesus), afforded the tyrants of this period opportunities for lavish display.

The geographical cleavage between the styles continued. The western temples at Syracuse, Selinus, Acragas, Paestum, Pompeii, Tarentum, Metapontum and Corcyra, and those in Hellas at Athens, Rhamnus, Delphi, Eretria, Aegina and Corinth, all were Doric. In the East, Naucratis, Ephesus, Samos, Naxos, Paros, Chios, Miletus and Magnesia furnish important landmarks of the archaic Ionic development. The Doric temple invaded the East, at Assos, suffering the intrusion of the Ionic frieze; reciprocally the Ionic temple penetrated the West, at Locri and Hipponium.

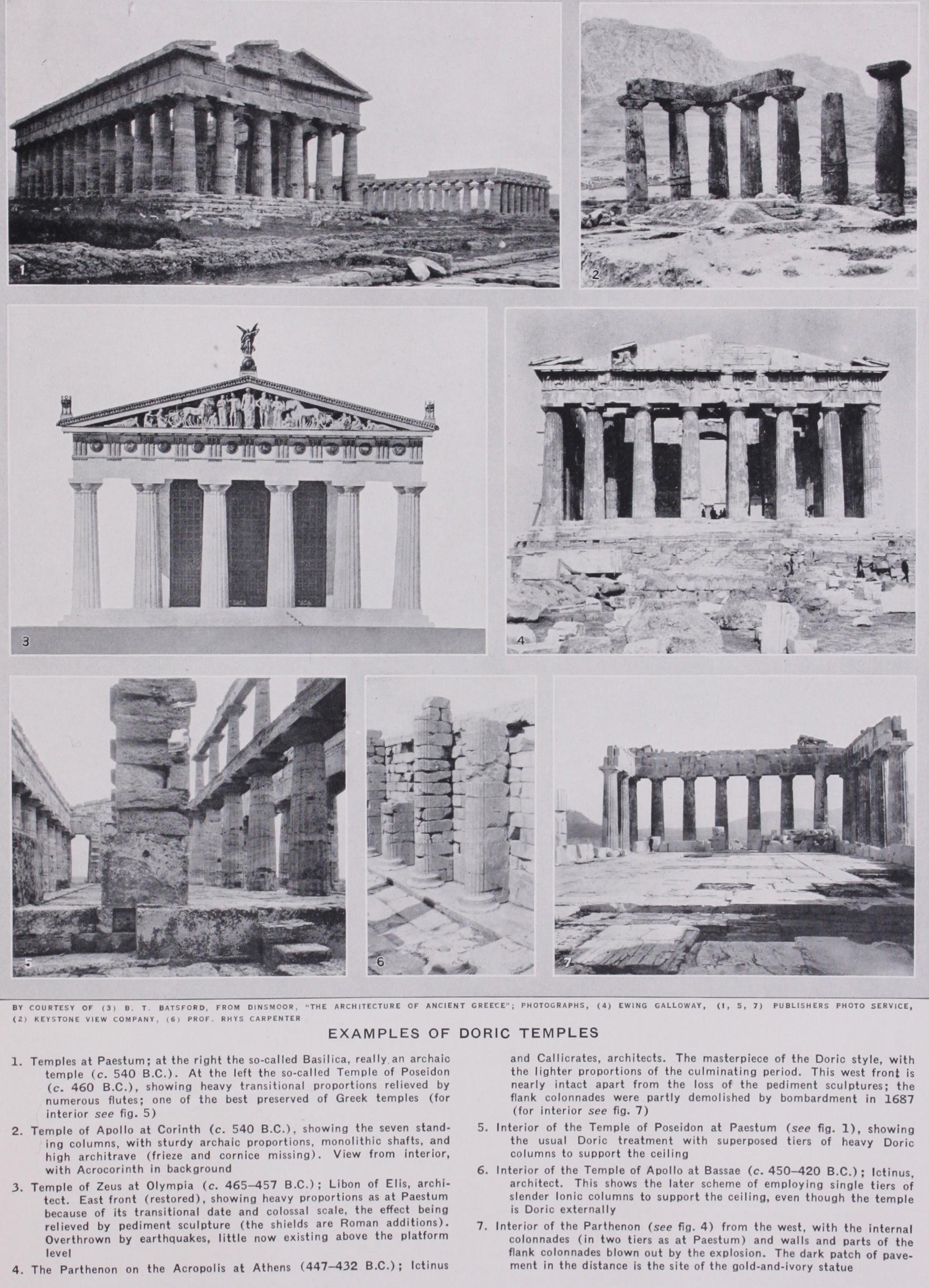

In the Doric order the sudden change of material, and timidity as to the strength of stone, caused violent changes. Not only were column shafts often constructed as monoliths, but propor tions became heavier, with column heights ranging from 64 to 4 diameters as they increased in size, and with intervals as close as diameter, so that the spreading capitals were nearly contiguous. With growing confidence, larger columns were eventually raised to 5 or even 5$ diameters, with intervals up to i diameters; only for constructive reasons were the colossal columns at Acragas limited to 43 diameters, the intervals at Selinus and Acragas to I/ and diameters. Spacings and diameters were often enlarged on the facades in Hellas; uniform diameters but different spacings characterize the western peristyles. Bulky architraves, and other members in proportion, made the height of the entablature more than half of the column, this proportion being reduced gradually to two-fifths or three-eighths.

The heavy shafts were. relieved by tapering and by flutes, 16 to 5o in number, 20 being the final preference. The hollow necking and astragal inherited from Aegean prototypes 3radually appeared, until three or four incisions alone distinguished necking from shaft. The abacus spreading to 23 times the upper column diameter (forming slabs up to 13 ft. square), making the echinus curve almost horizontal, contracted and the echinus stiffened. Triglyphs at first appeared only above columns, leaving horizontal oblong metopes between; interpolated triglyphs next reduced the metopes to vertical oblongs, which gradually approached ness, the half mutules above the narrow metopes then becoming of full width. Relief sculpture succeeded painting in the metopes and pediments, changing in the latter to free statues; human and animal forms replaced the semicircular xcroteria, and the antefixes changed from semicircles to prismatic forms, surmounted by palmettes. Such vagaries as flutes ending in petals, the echinus carved with rosettes or lotus, the architrave carved as a frieze or crowned by heavy Ionic mouldings, the frieze omitted, triglyphs lated to columns, pentaglyphs substituted for triglyphs—these show that the style was yet in a formative and uncanonized stage. The Ionic column, carrying a lighter entablature and longer habituated to stone, was more slender from the very beginning (about 8 diameters), with greater intervals (11 to 23 diameters) ; particularly noteworthy were the enormous intervals of the facades. Bases became more complex, a torus horizontally fluted above and a disc fluted or with two deep scotias below. The shaft had narrow flutes with sharp arrises, 18 to 48 according to size, the flutes later deepening with separating fillets, 24 in number.

The capitals show pendent leaves transformed into egg-and-dart, at first deeply undercut ; volutes changing direction to the hori zontal and becoming connected; "canals" at first convex, then con cave, with "eyes" appearing late in the development ; the abacus long and narrow. Exceptional were sculptured lower drums and rosetted volutes at Ephesus, flowered neckings at Naucratis, Samos and Locri. Though the entablature was friezeless, broad bands of relief sculpture were inserted wherever possible, as on the sima at sus. But in Hellas a new type of Ionic entablature was created to vie with Doric proportions ; the fascias of the architrave were suppressed, the dentils omitted and a high frieze inserted between architrave and cornice (Ionic treasuries at Delphi).

Both orders were awkward at the corners of peristyles. In the Doric, the difficulty lay in reconciling triglyph and column spacings, while bringing a triglyph out to the corner of the entablature; in the West it was met by widening the angle triglyph or the adjacent metope, in Hellas by con tracting the end columnar interval; finally, metope expansion was combined with col umn contraction. In the Ionic, the bracket capital seemed incapable of turning the corner, until at Ephesus was devised an awkward L-shaped capital with an angle volute.

Other forms displaying the versatility of the archaic designers were the hybrid Doric-Ionic capitals of Amyclae, the basket capitals of Delphi, and the use of human figures as supports, both male (Atlantes of Acragas) and female (Caryatids of Delphi). Other types of buildings yielded new opportunities,—simple temple-like treasuries (Olympia, Delphi), the square hypostyle hall (Telesterion) at Eleusis, the archaic circular tholos at Delphi, the apsidal senate-house at Olympia, altars as at Miletus and Delphi, the throne at Amyclae, porticoes such as the Athenian Stoa at Delphi, the primitive orchestra circle at Athens, and elaborate fountains built by the tyrants (Athens, Megara, Corinth, Samos). And in some of these minor works, as in votive columns and grave monuments, migratory architects mingled the styles.

Transitional Period (500-450 B.C.) .

The grammar of forms and the types of buildings having been largely determined, the next step was that of refinement. The problem was all the more concentrated because the political subjection of the East now re stricted architectural initiative to the Doric style of Hellas and the West, which, furthermore, received fresh impetus from the victories over Persia and Car thage. And in particular at Athens the discovery of copious marble quarries contributed to the refinement of design.Freedom was now abandoned in favour of strict canonization, resulting almost in monotony.

Hexastyle peripteral Doric tem ples became universal: in Hellas at Sunium, Athens (the unfinished Older Parthenon), Aegina, Del phi and Olympia ; in the West at Syracuse, Himera, Gela, Cau lonia, Acragas, Croton and Paestum (with simple in-antis plans at Acragas and Camarina) . Work was continued on the never finished colossi at Selinus and Acragas, with distinct changes of details. A reaction toward heavier proportions is every where noticeable; the column height ranged between 5s and 43 diameters, the intervals between i 4 and i diameter with smaller or larger columns ; the entablature remained about two fifths of the column height. In the West, columns were of uni form diameters and (except at Paestum) uniformly spaced on front and flank, apart from the contracted end intervals ; but in Hellas some emphasis of the front, either with heavier columns or with wider spacing, was still prevalent ; or the corner columns alone might be enlarged. The West adopted the opisthodomus of Hellas, sometimes in addition to the adytum ; but cella colon nades appeared in the West only at Paestum, apart from the huge octastyle at Selinus. Such internal colonnades were two (at Selinus three) storeys in height, separated by architraves and carrying only ceiling and roof ; the few known galleries (Aegina, Olympia) were later insertions; and the stone staircases (Selinus, Acragas, Paestum) ascended merely to storerooms above the ceilings.

In this period the Ionic temple first appeared in Hellas (Sun ium), with the peristyle strangely confined to one front and one flank, and with the typical main land form of entablature without fascias or dentils.

Among other types of build ings, additional treasuries at Olympia, the reconstructed ob long Telesterion at Eleusis and the similar Cnidian Lesche (club house) at Delphi, the Old Propy lon of the Athenian Acropolis, great porticoes such as the Royal and Painted Stoas at Athens, the reformed Athenian theatre with wooden scene buildings, and the imitation of the oriental gridiron city plan at Miletus, all paved the way for the masterpieces of the following period.

The Culmination at Athens (450-400 B.C.).

The middle period of the evolution centred at Athens, which signed peace with Persia in 448 B.C., and now in the absence of military require ments was free to use the wealth of the Athenian confederacy in rebuilding the temples ruined by the Persians. Under the personal initiative of Pericles, and in the hands of architects like Ictinus, Callicrates and Mnesicles, and the sculptors Phidias and Callima chus, Greek architecture reached its zenith.The Doric style of Hellas naturally retained the leading place, and was employed not only in hexastyle temples at Bassae, Rham nus, Sunium and Athens ("Theseum"), but also in the octastyle Parthenon on the Acropolis; besides these erected by Athenian architects, we find hexastyles near Argos (Heraeum), at Acragas (temple of Concord), Segesta and Delos (the last prostyle). Most of these structures were comparatively small, owing their effect rather to perfection of design and execution, and, in the case of those in Attica, to the beauty of marble. Columns were now more slender, 6 to 51 diameters high, with intervals of i 3 to I 4 diameters, as columns were smaller or larger ; the entabla ture was reduced to one-third of the column height. Only Bassae retained the older sys tem with heavier columns on the main facade and reduced spacing on both flanks ; else where uniformity prevailed, ex cept at the corners. Cella colonnades were omitted except in the work of Ictinus and at the Argive Heraeum ; Ictinus obtained a new effect by returning the colonnade across the back, at Bas sae separating adytum from cella (the lateral columns being engaged to the flank walls) , in the Parthenon forming an ambula tory around the statue. The false gallery with two storeys of Doric columns appeared for the last time in the Parthenon and Argive Heraeum ; a single Ionic order was preferred at Bassae (with three Corinthian capitals across the rear) and in the rear chamber of the Parthenon. The coalescence of the styles was marked by the inclusion of other Ionic elements, mouldings and continuous friezes (Parthenon, Theseum, Sunium) . Sculptured reliefs in friezes and metopes, pediments filled with statues and crowned by great floral acroteria, these and the fine mouldings and the marble ceilings enhanced by colour and gilding, broad masses of colour on triglyphs and in shadowed cornice soffits further relieved the simplicity of Doric forms.

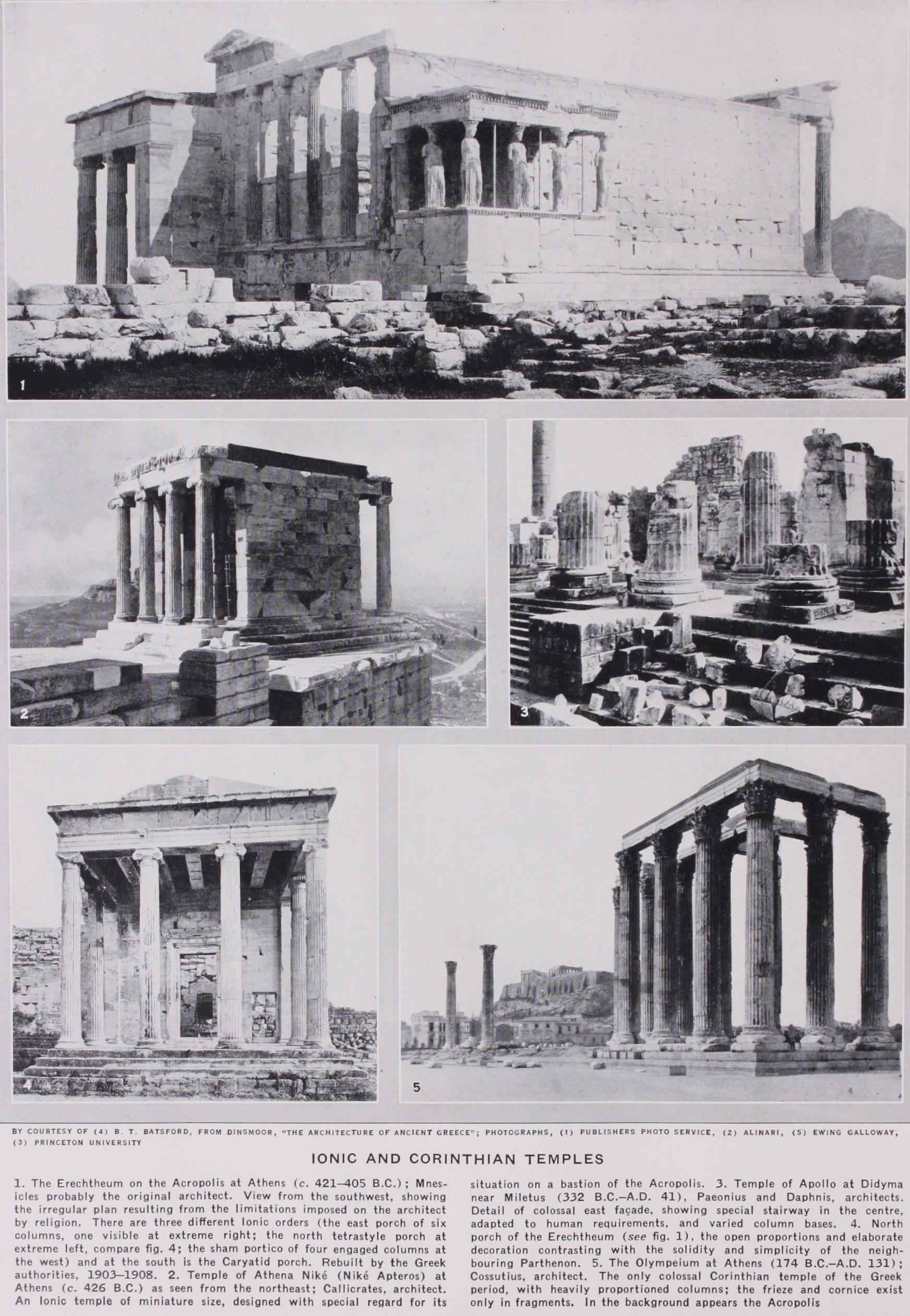

The Ionic style was also employed independently in three non peripteral temples at Athens (on the river Ilissus, the Nike temple and Erechtheum on the Acropolis)'; its foothold in Hellas was now assured. The amphiprostyle tetrastyle plan was preferred, though in the Erechtheum the rising ground at the east so elevated the stylobate that six columns were required in the width ; and the tetrastyle portico originally planned for the west end was revolved to the north flank to respect the sacred olive-tree, bal anced by the miniature Caryatid portico on the south, and replaced on the west by a sham portico of engaged columns, producing an irregular T-shaped plan. Columns tended toward slenderness but with great variety of proportion, from 7 7 to ro diameters, with intervals from 2 to 3 diameters, as columns were smaller or larger; the Doric rule was reversed to emphasize Ionic light ness. Bases, after an experimental flaring type at Bassae, assumed the Attic profile with one scotia between two tori. Capitals, apart from the experimental form at Bassae with angular volutes con nected by an arched cushion without an abacus, remained elongated brackets ; those of the Erechtheum were specially en riched by intermediate fillets in the volutes, inlaid gilded stems ending in palmettes, an extra torus moulding with coloured glass beads, and a flowered necking. The architrave, plain at first, soon resumed its fascias ; but the frieze had come to stay and in consequence the dentils were omitted, except in the Caryatid Portico which reproduces the Asiatic form ; and with these higher proportions the entablature was one-fourth or two-ninths of the column height. Rampant antefixes above the sima of the Erech theum, and its elaborately carved mouldings, exceptional in the 5th century, foreshadow the elaboration of the following period.

Another symptom of change was the creation of a third style, the Corinthian, first appearing inside the temple at Bassae. Like the Ionic capitals in the same colonnade, the Corinthian capitals represent an attempt to invent a form symmetrical on all sides, the basket capitals of Delphi being further elaborated with acanthus leaves, scrolls and palmettes.

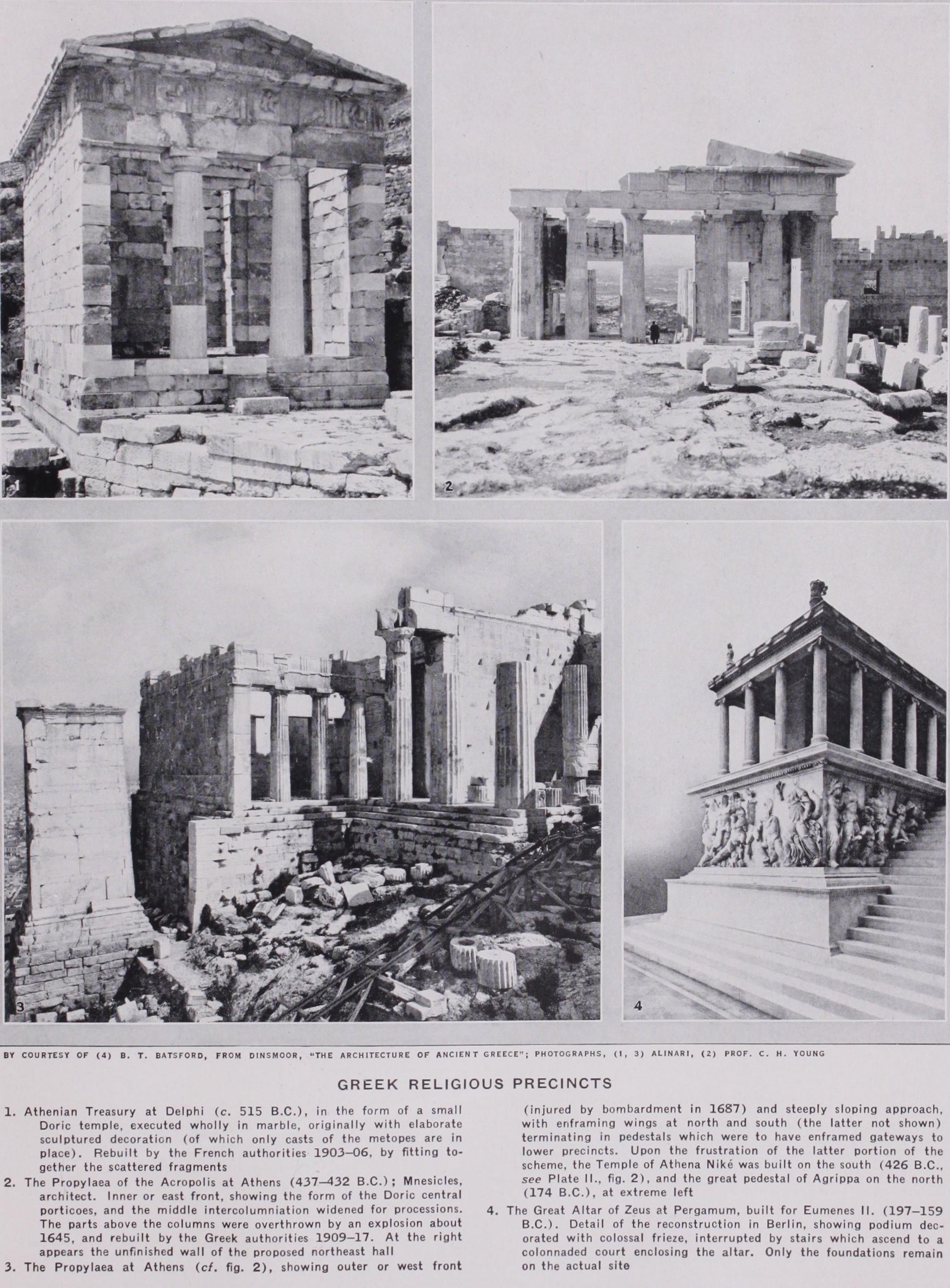

Among buildings other than temples, the Propylaea at Athens take first rank in brilliance of conception. A cruciform plan 224 ft. in length (about equal to the Parthenon) would have formed a frontispiece across the west end of the Acropolis, with wings pro jecting westward to enframe the ascent ; by war and priestly con servatism the design was curtailed until it resembled a lopsided T, only 154 ft. in length. The central building, with its Doric hexastyles and pediments dom inating the low hipped roofed north and south arms and west wings (without columns except on the return faces of the wings), formed the entrance, the central intercolumniation widened 6 ft. to allow the passage of festal processions, and the five doorways graded in width like the intercolumniations, with heights varying in proportion ; the west ceiling was supported by six Ionic columns in immediate juxtaposition with the Doric. Hardly less notable were the redesigned Telesterion at Eleusis, a great square with four rows of five columns within (planned with an outer pseudodipteral colonnade), and the Odeum at Athens with internal columns arranged in nine rows of nine ; both had clerestory lanterns above the roofs. Corresponding advances in city planning were the importation of the gridiron system to Hellas (Peiraeeus) and the West (Thurii), and the in vention of the fan system at Rhodes.

In these buildings, beauty of proportion was enhanced by "optical refinements," almost a speciality of the culmination. The curve of the platform, rising a to 4i in. in a circular arc with a radius as great as 3-1 miles, gave vitality and corrected any sagging illusion in the colonnade. The entasis or swelling outline of the column shaft, preventing any sensation of concavity, attained its maximum (4 to a in.) at half of the height, though in earlier and later periods it was much more pronounced. The inward inclination of the column axes (from $ to 3s in.) gave a pyramidal illusion of greater stability, the axes of the flank colonnades of the Parthenon meeting more than a mile above the pavement ; walls, antae and other supposedly vertical surfaces might show similar inclinations. And the manner in which the various mem bers were adjusted to each other, preserving these delicate rela tions and yet keeping the joints invisible, represents a triumph of calculation and stonecutting.

Fourth Century (400-300 B.C.) .

The displacement of the political centre from Athens successively to Sparta, Thebes, Mace donia and Asia Minor was accompanied by unmistakable evidence of a decline from aesthetic perfection. The service of the gods began to be subordinated to that of men, and from the temple attention was diverted to a great variety of structures correspond ing to the varied requirements of a more complex civilization. Even in religious architecture the striving for diversity and in novation is manifest in the increase of excessive ornament.In Hellas the Doric style was still preferred for temples, but, incapable of further perfection, was now modifi:d. Hexastyle plans (Delphi, Epidaurus, Tegea, Nemea, Stratos, Delos, Ptoon and Olympia) were often shortened by omitting the opistho domus; temples at Delphi and Epidaurus were hexastyle prostyle. Columns were more slender (5i to 6i diameters) and entabla tures correspondingly lower (one-quarter of the column height), the reduction occurring in architrave and cornice while the frieze remained high to preserve the squareness of metopes. The enrichment of the sima by carved rinceaux and rampant antefixes was counterbalanced by the loss of such deli cacies as the hyperbolic echinus profile.

Following the example of Bassae, Cor inthian internal columns were employed at Tegea, Stratos and Nemea, Ionic at Epidaurus; an inner row of Ionic columns lined a Doric facade at Delphi.

More important was the Ionic sance in Asia Minor. Not only hexastyle plans as at Priene, but colossal octastyles again became the fashion, at Ephesus peating the archaic plan, at Sardis omitting the inner flank colonnades and becoming semipseudodipteral. Even the decastyle plan with i 20 external columns appeared at Miletus, with the cella unroofed (hypaethral). Column proportions tinued to be slender (84 to 9a diameters high), though because of the enormous dimensions the intervals were contracted (14. to I* diameters) ; some facades (Sardis, Ephesus) show however mous central spacings. Such abnormal embellishments as tured pedestals, bases, drums and capitals were confined to the larger temples. The entablature always lacks the frieze (except at Miletus where the work was protracted into Roman times), and hence is only one-sixth or one-seventh of the column height. Only in Hellas (tholos at Olympia) or in non-religious and hence less conservative Asiatic structures, executed with collaborators from Hellas (Mausoleum at Halicarnassus), did the frieze penetrate the entablature, now always in combination with dentils, giving the more satisfactory proportion of one-quarter of the column height.

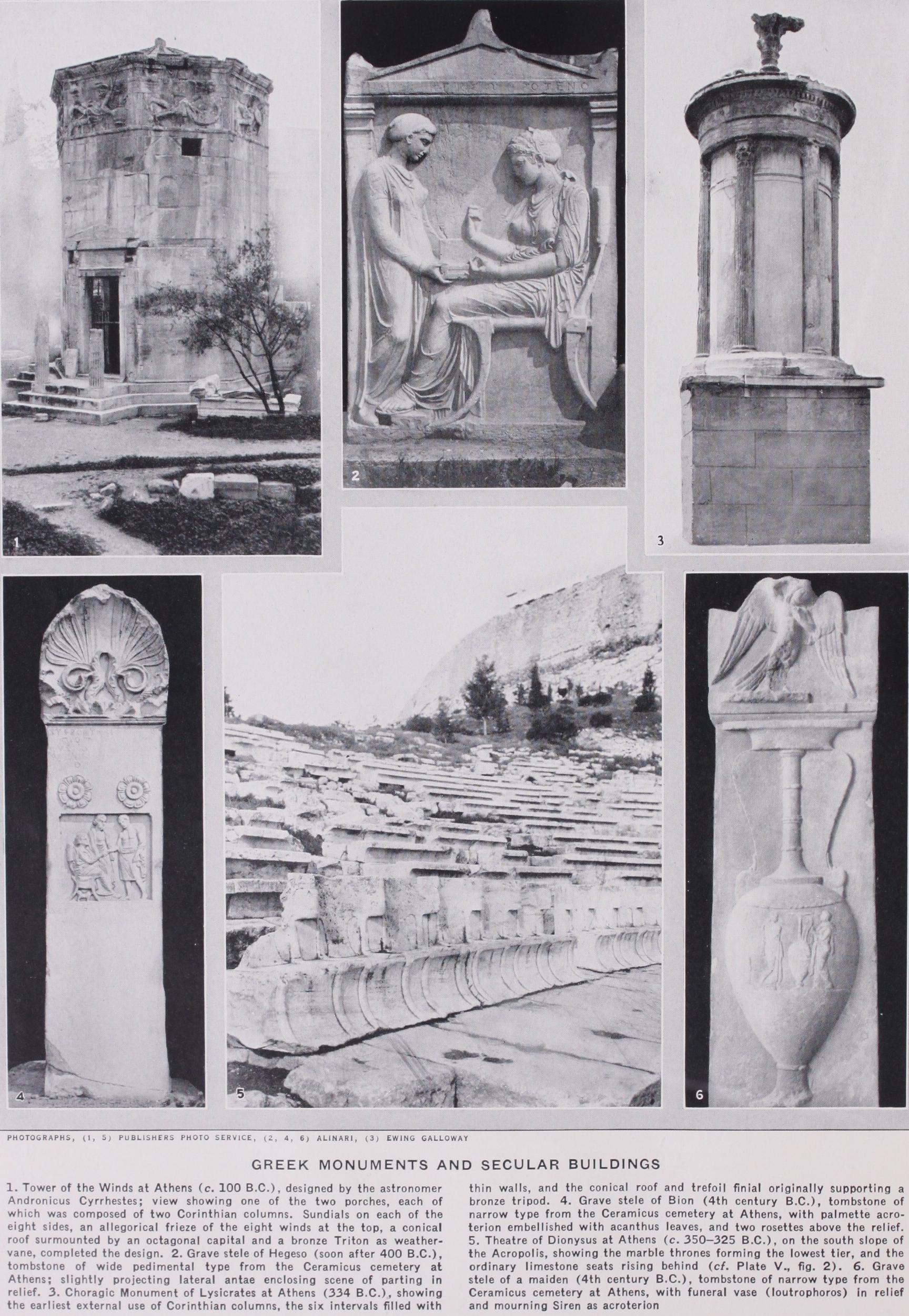

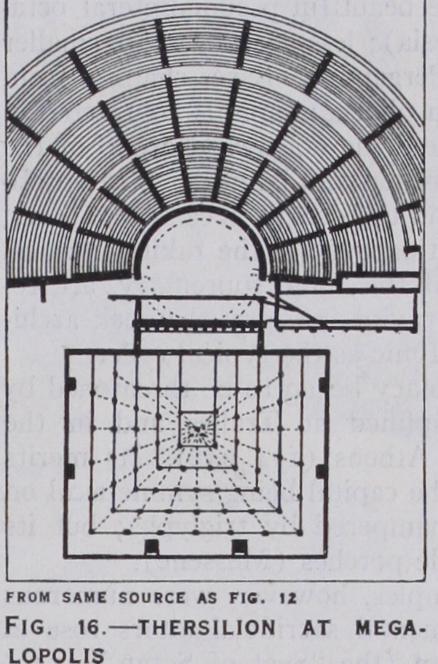

Important buildings other than temples were erected in both styles. In the Doric a peristyle at Thoricus, treasuries at Delphi, choragic monuments at Athens, tholoi at Delphi and Epidaurus, the huge dodecastyle facade of the Telesterion at Eleusis and the analogous assembly-hall (Ther silion) at Megalopolis, porticoes up to 55o ft. in length as at Cor inth, the Arsenal of 43o ft. at the Piraeus, the Lion tomb at Cnidus (another Doric intrusion in the East), all testify to the vitality of the style. The tholos was re produced in the Ionic style at Olympia ; monumental Ionic tombs in Asia Minor, the Nereid monument at Xanthus (a temple raised on a lofty pedestal) and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (with a pyramid in turn elevated above a peristyle of 36 columns, attaining a height of 136 ft.), have remained unsurpassed in their field.

The Corinthian capital was developed as a secondary feature inside temples at Tegea, Nemea, Stratos and Miletus, inside tholoi at Delphi, Epidaurus and Olympia; but not until 334 B.C. was the style used independently and externally in a choragic mon ument at Athens, with an entablature devised by combining Attic frieze with Asiatic dentils.

A few non-columnar designs require special mention. The Attic tomb stele with its ever-deepening frame of miniature antae and entablature, or with an elaborate floral acroterion, became extinct as the century ended. But the theatre, now provided with a stone auditorium encircling more than half of the orchestra (Athens, Epidaurus, Eretria), its one-storeyed scene building (also in stone) containing several great openings and flanked by pro jecting pavilions (parascenia, at Athens exceptional in being colonnaded), was yet in its infancy. The stadium, either round ended or rectangular, repeated the theatre form. The market place (agora) became, if not strictly rectangular, at least more formal; and the newly founded or rebuilt cities of the period followed the gridiron plan (Priene and Cnidus).

Hellenistic Period (300-100 B.C.).—The even balance tween East and West which had characterized the ing century was overthrown by the transference of the cal centres to the oriental doms of Alexander's successors, resulting in the domination of the oriental elements in Greek architecture. The Doric style, now on the downward path, appeared chiefly in small temples, either in-antis (Selinus, Acragas, Taormina, Ilium) or prostyle (Pergamum, Lycosura, Samothrace, Gortyna, Oropos) ; belated peripteral hexastyles occur at Acragas, Pergamum and Lebadea —the last symbolic, the abandoned scheme of an eastern arch (I 74 B.c.). A proposal to erect a Doric temple at Teos was actually countermanded in favour of the Ionic style; tects frankly wrote that "sacred buildings ought not to be structed of the Doric order" because of the difficulty of spacing triglyphs and columns. The few who adhered to the style sought new methods of appeal: engaged columns, lighter proportions with slender columns (up to 7 or 7a diameters) and thin entablatures requiring the interpolation of extra triglyphs; columns with Ionic fluting or even bases; the echinus, abacus and taenia moulded. Wall surfaces were modelled, with emphasized joints and belt courses. The cella might even have an internal apse (Lebadea, Samothrace), or projecting aisles at the sides (Lusoi).

The Ionic style, now the successor rather than rival of the Doric, is best exemplified in three beautiful pseudodipteral octa styles (Messa, Smintheum, Magnesia) ; less successful are smaller examples at Teos, Magnesia and Pergamum. Bases changed from the Asiatic to the Attic form, with plinths; capitals contracted in length ; the rising echinus eliminated the downward droop of the cushion, and rinceaux filled the cushion and baluster. The entab lature included the Attic frieze, and the dentils became small and meaningless, being used as decoration even in the raking cornice. These forms, and this moment of the Ionic supremacy, are re flected in the volume wherein Vitruvius interpreted Greek archi tecture to the Romans, using the Ionic as the typical order.

Now, however, the Ionic supremacy began to be threatened by the Corinthian style, best exemplified at Tralles and in the dipteral octastyle Olympieum at Athens (1 74 B.e.). Its merits were most obvious in peristyles, the capital being symmetrical on all sides and the entablature unhampered by triglyphs; but its popularity extended even to distyle porches (Messene) .

Even more important than temples, however, were numerous other types of buildings. Monumental sacrificial altars rose at Syracuse (74X653 ft.), Pergamum (the "Seat of Satan," II2X I2o ft.), Priene, and Magnesia. Doric porticoes surrounding the temples (Ephesus, Priene, Magnesia) ; vast stoas built by Hel lenistic kings for the cities of Asia (Pergamum, Assos, Priene) and Hellas (Delos, Delphi, Athens, Megalopolis, Olympia), or, with slight modifications, used as market-halls (Aegae, Alinda, Assos) and libraries (Pergamum) ; monumental propylaea (Samo thrace, Delos, Lindos, Epidaurus, Olympia and Selinus), the tholos at Samothrace, the hypostyle hall at Delos and gymnasia (Epi daurus, Priene) ; all repeated earlier forms with slight variation. The long "Hall of the Bulls" at Delos surmounted at one end by a tower, the soaring lighthouse of 40o ft. at Alexandria, and small senate-houses with semicircular or rectangular auditoria imitated from the theatre (Miletus, Priene), were innovations. The theatre itself received a colonnaded stone proscenium before the scene building, of which the great openings were elevated to an upper storey (Oropos, Epidaurus, Priene, Ephesus). Commemorative monuments were more lofty, high pedestals (Delphi, Athens) or pair of columns supporting entablatures (Delphi), forerunners of the Roman triumphal arch. Private houses changed from the megaron type to the peristyle court (Priene, Delos), and in their likeness were designed great hotels with central courts (Epidaurus, Olympia). The market-place became a formally enclosed rectangle (Magnesia) rather than a picturesque group of colon nades and public buildings. The roads outside the city gates were lined with an ever increasing variety of sepulchral monu ments, including the Mausoleum type (Acragas, Mylasa) and tumuli with vaulted chambers (Pergamum).

The conquest of the Orient had brought Greece into contact with the arch and vault, now freely used in supporting great masses over openings, as in city gates, retaining walls, corridors, staircases and sepulchral chambers. Sloping or intersecting barrel vaults were not uncom mon. The post-and-lintel system was by no means supplanted, but the vaulting system of the Orient was being perfected, ready for the Romans to assimilate with their Etruscan traditions (see