Chosis

CHOSIS).

Head-hunting is therefore associated (I) with ideas regarding the sanctity of the head as the seat of the soul, (2) with some forms of cannibalism where the body or part of the body is con sumed in order to transfer to the eater the soul matter of the viand, (3) with phallic and often fertility cults intended to imbue the soil with productivity, and may thus develop into human sac rifice, a practice which has been generally associated with agricul ture. Head-hunting, or at any rate some practice closely allied to it, is found sporadically all over the globe either actually existing or in some degenerate survival.

In Europe the actual survival of the practice is probably limited to the Balkan Peninsula, where the taking of the head affects the future life of the soul in some way that is no longer quite clear, but no doubt implied the transfer of the soul matter of the de capitated to the decapitator. Here the complete head was taken by Montenegrins at any rate as lately as 1912, the head being carried by the lock of hair worn apparently for that purpose. In the Balkan war of 1912-13, nose taking was substituted, and it was the practice to cut off the nose and upper lip with the mous tache by which it was carried instead of the whole head, just as in Kafiristan and in Assam an ear is sometimes carried off instead of the whole head. In the British Isles the practice continued ap proximately to the end of the middle ages in Ireland and the Scottish marches, and, in the case of the Irish, Strabo accused them of honouring their dead relatives by eating their corpses, while a Martinmas pig is still killed that the fields may be sprinkled with blood and so rendered fertile. In some parts of the Conti nent murderers have been known to eat part of their victims to secure themselves against ill-will on the part of the ghost. The underlying idea is, no doubt, that the consumption of the flesh leads to spiritual identity.

In Africa the principle involved has shown itself rather in the form of human sacrifice than of true head-hunting, Dahomey and Ashanti being notorious examples ; but even here the fact that the human sacrifices in Dahomey made the rain-magic more efficacious suggests the working of the same ideas, while we hear of a Matabele chief who anointed his body and fertilized his fields with human fat. So, too, the eating of an enemy's heart has been reported from Dahomey and Whydah, and the use of skulls as drinking cups from the Guinea coast. Bona fide head-hunting occurs in Nigeria, where a number of usages strongly suggest Indonesian culture. As in Indonesia, head-hunting among the Kagoro, and perhaps other tribes in Nigeria, is associated with the fertility of the crops and with marriage and with the service by the victim of the taker of his head in the next world.

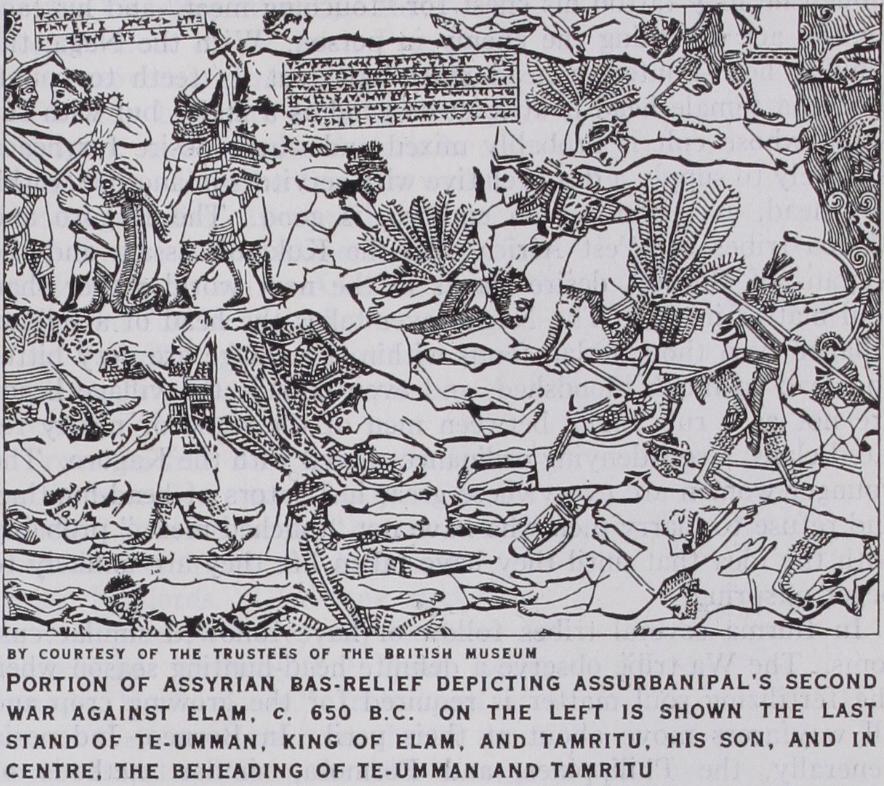

In Asia Herodotus mentions head-hunters, and on a bas-relief from Nineveh in the British Museum is represented a battle in the 7th century B.C. between Assurbanipal and the king of Elam, in which the Assyrians are depicted as cutting and carrying off the heads of the slain. In Kafiristan on the north-west frontier of India head-hunting was practised until a recent date, wheat being showered by the women upon men returning with heads from a successful raid. In the north-east of India, Assam is famous for head-hunting. All the hill tribes living south of the Brahmaputra —Garos, Khasis, Nagas and Kukis—were head-hunters in the past, and many of the Naga tribes still practise the decaying cult.

Head-hunting in Assam is normally carried on by parties of raiders who depend on surprise tactics almost entirely. The heads, and sometimes also the hands and feet or even the whole limbs, are cut off and carried home to the village, where the head is usually placed on a stone or pile of stones kept for that purpose. The practice of cutting off the limbs has possibly a different origin, as there are tribes north of the Brahmaputra who do not take heads, but do cut off the feet and hands of slain enemies, pre sumably with a view to incapacitate the ghost. The skull is sub sequently variously treated. After its virtue has passed into the stone on which it is laid it is either buried face downwards, as by the Angami tribe, hung up in trees, as by Semas and Lhotas, or suspended in the chief's house, or the bachelors' hall. In the latter case some tribes decorate it with a pair of buffalo horns, probably as a fertility symbol, and with long tassels of a broad bladed grass which rustle pleasantly when the skull is swung by a dancer at a feast. In the case of several participants in a raid who are all in at the death, the head is often divided on a fixed system, certain definite portions going to the first, second and third spears, etc. The insignia and, where tattooing is practised, the tattoo patterns worn by the successful warrior have specific reference to success in head-hunting. Thus the Angami warrior wears one hornbill feather for each success--"touching-meat" as it is called, while the Konyak warrior has his neck tattooed only if he has actually performed the act of decapitation in person, though he may tattoo his chest for "touching meat" and his face for the act of killing the enemy in person. With the Naga, the genuine head-hunter, a head must have cut its teeth to count, though a female head is at least as good as a male ; but with the Kuki, whose cult is probably mixed and whose desire for heads is merely to supply a dead relative with servitors in another world, any head, even that of an embryo, is good. The Kagoro and Moroa tribes of West Africa, like the Kuki of Assam and the Kayans of Borneo, desire slaves in the next world rather than soul matter in this. The Naga never takes the head of a fellow villager even though clan feuds within the village are very bitter and lead to much bloodshed, and even outside the village heads are not as a rule taken between men of the same or nearly re lated clans, a self-denying ordinance shared with the Kagoro. The younger women are everywhere great instigators of head-hunting, and refuse to marry men who have not "touched meat," probably with the idea that until they have taken life they are unlikely to beget offspring.

In Burma several tribes follow or have followed similar cus toms. The Wa tribe observe a definite head-hunting season when the fertilizing soul matter is required for the growing crop and all wayfarers move about at their peril. In Borneo, Indonesia generally, the Philippines, and Formosa, similar methods of head-hunting obtain, and the hill tribes of Malaya and Indo-China probably are or have been head-hunters at some period. The Ibans of Borneo are particularly enthusiastic in this respect. The prac tice was reported of the Philippines by Martin de Rada in and has barely disappeared among the Igorot and Tagalog of Luzon, while in Formosa it prevailed among the hill tribes. Else where in Indonesia it extended through Ceram where the Alfurs were, or are, head-hunters, to New Guinea, where the Motu, like the Lhota Naga of Assam, wears a hornbill's head as the insignia of his achievement ; here and there, as in the Battak country and in Timorlaut, it seems to be replaced by cannibalism.

In New Guinea the Tugeris use a bamboo knife for the act of decapitation, perhaps because iron would adversely affect the soul within. Throughout Oceania head-hunting prevailed till compara tively recently and possibly still occurs in the Solomon Islands. In the Solomon Islands the actual expedition to obtain a head formed the climax in a series of ceremonial acts extending over a num ber of years, and the suppression of head-hunting, on which de pended an important part of the social life, has been a serious factor in the decay of society and the decrease of population which has followed under British administration. (See AN THROPOLOGY.) Throughout Oceania head-hunting is closely asso ciated with cannibalism and the latter institution has tended to obscure the former, but in many islands the importance at tached to the head is unmistakable. In parts of Micronesia the head of the slain enemy was paraded about with dancing which served as an excuse for raising a fee for the chief to defray public expenditure, after which the head would be lent to another for the same purpose. In Melanesia the head is often mummified and preserved, and sometimes, as in New Britain, seems to be worn as a mask in order that the wearer may acquire the soul of the dead man. Even in Australia this underlying principle seems active as it is reported that the Australian believes that the spirit of a slain enemy enters the slayer. In New Zealand the heads of the foe were dried and preserved so that the tattoo marks and often the actual features were recognizable; this practice led to a develop ment of head-hunting when tattooed heads became desirable curios and the demand of Europe for Maori trophies caused "pickled heads" to become a regular article of trade and export.

In North America the general practice was to take the scalp rather than the head, the idea probably being that the soul is lo cated in the hair, an idea present in the Biblical story of Samson, common in Malaya and Indonesia, where Nagas and Borneans use the hair of their dead enemies for ornaments, as did the North American Indians; in Oceania where the Marquesans use the hair of the victims of their cannibal rites for making arm rings and necklets of magic virtue; and frequent in South America, where the heads are often preserved, as by the Jibaros, by removing the skull and packing the skin with hot sand, thus shrinking it to the size of the head of a small monkey while preserving the fea tures intact as a vivid portrait in caricature. Here, again, head hunting is probably associated with cannibalism in a ceremonial form, and the heads of certain animals are also treated similarly (see LYCANTHROPY).

Head-hunting, therefore, is world-wide. It is associated with tribes still living in the stone ages, and may even go back to palaeolithic times; as in the Azilian deposits at Ofnet in Bavaria heads were found carefully decapitated and buried separately from the bodies, indicating beliefs in the special sanctity or importance of the head.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A. J. N. Tremearne, Tailed Head-hunters of Bibliography.-A. J. N. Tremearne, Tailed Head-hunters of Nigeria; T. C. Hodson, "Head-hunting among the Hill Tribes of Assam" (Folklore, xx.) ; A. C. Haddon, Head-hunters: Black, White and Brown (London, 19o1) ; D. Cator, Everyday Life among the Head-hunters (London, 005) ; C. Hose and W. McDougall, Pagan Tribes of Borneo (1912) ; Freiherr von Heine-Geldern, "Kopfjagd and Menschenopfer in Assam and Birma" (Anthropolische Gesellschaft, 1917) ; W. H. R. Rivers, Depopulation of Melanesia (Cambridge, 1922) ; J. H. Hutton, "Divided and Decorated Heads as Trophies" (Man, XXII., viii.), "Significance of Head-hunting in Assam"; F. W. K. de Graff, The Head-hunters of the Amazon (London, 1923) ; Karston, "Blood Revenge, war and victory feasts of the Jibaro Indians of Eastern Ecuador" (Bull. 79, Bureau of American Ethnology, 1923) ; E. Durham, "Head-hunting in the Balkans" (Man, Feb. 1923) ; Thomson, "Shrunken Human Heads" (Discovery, July 1924) .

(J. H. H.)