Comparative Physiology of Heart

HEART, COMPARATIVE PHYSIOLOGY OF. Mech anisms for the circulation of fluids through the body are found in all except the simplest forms of animals, and such mechanisms appear to be a necessity for all animals which have specialised organs for respiration, digestion or excretion. Some of the chief functions of the circulation are as follows: (r) To carry oxygen from the organs of respiration to the rest of the body; (2) To carry food materials from the organs of digestion to the rest of the body; and (3) to remove from the tissues their waste prod ucts and to carry these to the organs of excretion. The transport of oxygen is the most urgent of these functions of the circulation because all animal tissues use oxygen continuously but are unable to store significant quantities. Hence the activity of all animal tissues is dependent on the circulation delivering to them a con tinuous supply of oxygen. The importance of the oxygen carrying function of the blood is indicated by the fact that the blood of nearly all animals contains some form of pigment that can com bine with and transport to the tissues considerable quantities of oxygen. The haemoglobin of vertebrate blood is the best known of these pigments. The muscles that move the body use oxygen freely and the chief factor limiting continued muscular activity is the efficiency of the circulation; hence animals of an active habit of life require a much more efficient circulation than do animals which perform few movements. Animals do not develop complex mechanisms for which they have no need and hence the degree of development of the circulation varies to an extraordinary de gree, because the complexity of circulatory apparatus needed de pends on the mode of life of the animal and this often varies greatly in closely related animals. For example, of two Crustacea one may swim vigorously and the other may be sedentary, and in such a case the former will have a far better developed circu lation than the latter. Generalisations concerning the circulation are therefore difficult, because in a single order of animals very wide variations in the development of circulatory mechanisms may exist. In this article examples will be chosen from those species which have a relatively well developed circulation, and the species with rudimentary or vestigial circulatory mechanisms will not be considered.

Tubular Hearts.

The common earth worm provides an ex cellent example of a primitive type of circulation. Down the back runs a tube filled with blood and down this tube from the tail to the head pass regular waves of contraction moving at a rate of about half an inch a second. These waves of contraction squeeze the blood forward just as a thin rubber tube can be emptied by drawing a finger and thumb down it. Waves of contraction of this nature which pass along a struc ture are termed peristaltic waves. The blood is squeezed from the dorsal artery into arterioles, these connect with small veins and the veins empty into a ventral vein which returns the blood to the dorsal artery. Tubular hearts of this character may be regarded as the primitive type from which the more complex hearts have been developed. Hearts of this type are found in the worms and also in the ascidia. These last are a primitive group, which form a link between invertebrates and vertebrates. Moreover, the heart of the embryo vertebrate commences as a tubular structure.

The Arthropod

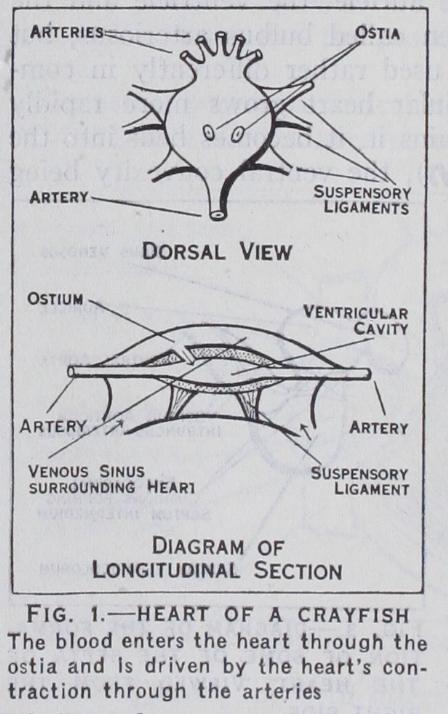

vast majority of living animals belong to the arthropod phylum which contains such classes as Crustacea, Arachnida and Insecta. This phylum may be divided into two great groups: firstly the Crustacea which breathe by gills, and secondly the spiders, scorpions and insects which are mostly land animals and which breathe partly or entirely by tracheae.In the whole class of arthropods the circulatory apparatus has certain features in common. The heart is surrounded by a venous sinus and the blood passes into the heart by means of holes or ostia provided with valves. When the heart contracts the contrac tion closes the ostia and drives the blood out through arteries. In most forms there is no proper system of capillaries and veins but the organs are surrounded by venous sinuses.

The gill breathing forms have fairly powerful hearts and fig. i shows the heart of the crayfish. The king-crab Limulus is note worthy because it has a better developed circulatory system than any other arthropod. This form is a survival of a primitive type of arthropod and is intermediate between Crustacea and spiders. It possesses a closed circulatory system of arteries, capillaries and veins, and an exceptionally powerful heart. On the other hand, some of the smaller Crustacea have only very rudimentary circula tory mechanisms, without any true heart. The hearts of Crustacea are superior to those of other arthropods but are distinctly in ferior to those of the molluscs; for example, it is fair to compare a crab and an octopus of similar size for both are cold-blooded, sea-living, gill-breathing animals of about equal activity, but the heart of the crab is a far simpler and weaker form of pump than is the heart of the octopus.

The tracheated arthropods include the spiders, scorpions and insects and all of these have extremely simple and inefficient hearts. The typical heart is a tubular structure running along the dorsum and is divided into segments by valves. Waves of con traction pass from behind forward driving the blood either for ward or out through lateral arteries. The reason for the im perfect development of the heart in these forms is that they are not dependent on the circulation for their supply of oxygen, but breathe through minute branching tubes or tracheae which carry air from the surface of the body direct to the cells. This is a very efficient and economical respiratory mechanism for animals up to a certain size, as is indicated by the success of the class Insecta which contains more than half of the known species of ani mals, but in which the vast majority of species are less than one gram in weight.

Molluscan Hearts.

The molluscan circulation is arranged as follows: The blood returning from the body is collected in auri cles and these contract and squeeze the blood into the ventricle which expels it into arteries. This arrangement forms a striking contrast to the arthropod heart in which the ventricle is suspended in a venous sinus. The contractile auricle ensures the proper filling of the ventricle, and represents an important advance in the effi ciency of the heart as a pump. The vertebrate heart is of course constructed on the same principle.In the highest molluscs, name ly, the cephalopods (e.g., octo pus) the circulatory mechanism is complex, for in addition to the chief heart accessory hearts are provided to pump the blood through the gills. This arrange ment is shown in fig. 2. The dif ference between the efficiency of the arthropod and molluscan hearts is indicated by the fact that in the lobster, which is a particularly active crustacean, the arterial pressure is only i 2cm. of water, whereas in the octopus the arterial pressure may rise as high as i i Scm. of water.

The Development of the Vertebrate Heart.

A comparison of the circulation in the different classes of vertebrates reveals a series of arrangements of increasing complexity and efficiency. The vertebrates are descended from sea living forms and the hearts of the fishes may be compared as regards efficiency and complexity with the hearts of the higher molluscs. The change from water to land involved the substitution of lungs for gills, and this necessitated a considerable increase in circulatory efficiency. The heart of a frog, for example, is larger, more complex and much more efficient than the heart of a fish of the same size. The acquirement by vertebrates of the power to maintain a constant body temperature considerably above the temperature of their surroundings was a further change that involved even greater demands on the circulation, because the rate of oxygen consump tion is far higher in warm blooded than in cold blooded animals, and in fact the circulatory mechanisms of the birds and mammals are far more powerful and efficient than those of any invertebrates or cold blooded vertebrates.

Fish's Heart.

The heart of an elasmobranch such as the dog-fish is a good example of a primitive vertebrate heart. It con sists of four divisions, the sinus venosus, the auricle, the ventricle and the bulbus arteriosus. Each of these chambers is divided by valves from its neighbours and the heart functions by a wave of contraction which passes down from the sinus to the bulbus arte riosus, and drives the blood be fore it from one chamber to an other. This wave of contraction passes at a rate of about 4in. a second. When one chamber con tracts, a certain interval is necessary to allow the blood to pass into and distend the next chamber and this time is provided by the wave of contraction being delayed for a fraction of a second be tween each of the chambers. The muscles forming all the cham bers have the power to contract rhythmically without any stimulus being applied, but the natural rhythm of the sinus muscle is the highest and hence the sinus acts as a pacemaker to the rest of the heart. On the whole the hearts of the different classes of fishes do not differ in any important respect. The lampreys are the most primitive group of vertebrates and their hearts are slightly more primitive than the dog-fish heart, but the general arrangement and properties are the same. In the teleosts there is no true bulbus ar teriosus, but otherwise there is no important difference from the elasmobranch heart. The dipnoi of lung fishes, however, show an important variation. This order is only represented by a few scat tered species, but these show the first primitive attempt of a water living vertebrate to acquire the power of air breathing. They pos sess lungs, and the veins from the lungs open into a portion of the auricle, which is separated from the rest by an incomplete septum. The oxygenated blood coming from the lungs is thus separated in the heart from the reduced blood that comes from the rest of the body.

Amphibian

frog is a good example of this group and its heart shows special arrangements necessitated by air breathing. A special auricle has developed on the left and in this the aerated blood from the lungs is collected. The ventricle is not divided, but a complex system of valves in the bulbus arterio sus ensures that a large propor tion of the aerated blood from the lungs shall pass to the head whilst a large proportion of the oxygen-poor venous blood from the rest of the body shall pass to the pulmonary arteries. Fig.3-C shows the manner in which the frog's heart is developed by the convolution and differentia tion of a simple tubular struc ture. The mechanism of the frog's heart is one of the simplest examples of a double circulation, that is to say, of an arrange ment by which the blood is alternately passed through the lungs to be oxygenated and then through the body to provide oxygen to the tissues. The actual mechanism for the separation of exhausted and oxygenated blood appears to be very imperfect in the case of the amphibian heart, and this may be one reason why the amphibia are a relatively unimportant group of animals.

Reptilian Hearts.

The process of division of the circulation into two distinct circuits is carried to completion in the reptiles.In all reptiles there are two distinct auricles; in most genera the ventricle is only partly divided, but in the crocodiles the ventricle is divided into two separate chambers and thus the pulmonary or lung circulation is completely separated from the systemic or body circulation.

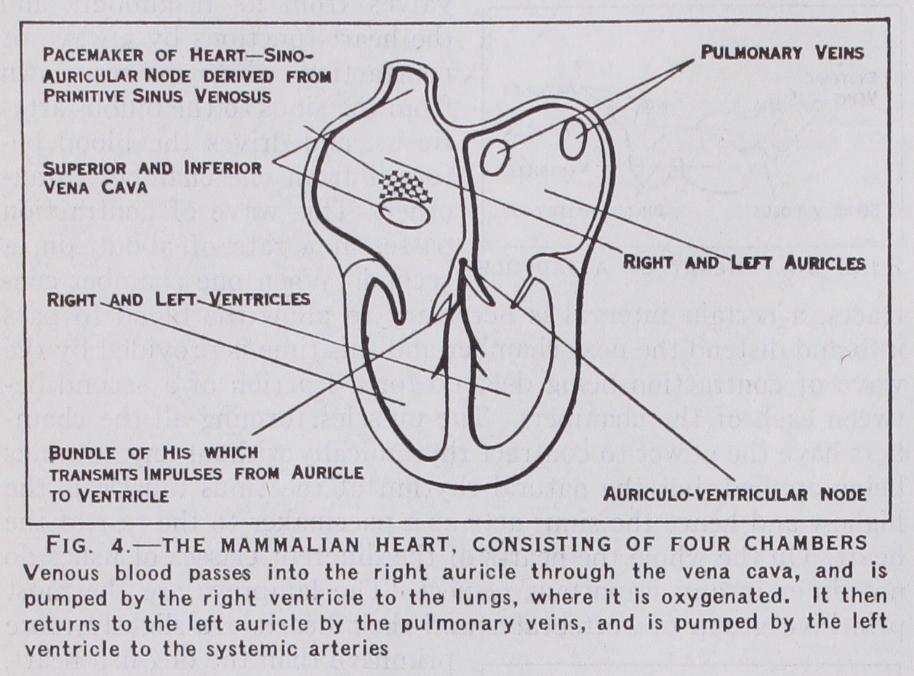

Birds and Mammals.

The hearts of the birds and mammals are more complex and far more powerful pumps than are those of the cold blooded vertebrates. The heart consists of four cham hers, two auricles and two ventricles. The right auricle which receives the blood from the body represents the sinus venosus and the right portion of the auricle of the fish. The sinus venosus is reduced to a small but very important piece of tissue around the superior vena cava, an area known as the pace-maker of the heart (cf. fig. 4). The left auricle, which receives the blood from the lungs, represents the left half of the fish's auricle. The two ventricles have been derived by division of the single ventricle seen in the fish, whilst the bulbus arteriosus of the fish has disap peared. In this type of heart the venous blood returning from the body is collected in the right auricle and passes to the right ventri cle which pumps it through the lungs. The lung veins return the blood to the left auricle and the left ventricle pumps the blood to the body tissues.

Conduction System.

The hearts of warm blooded animals have to work at a far greater pace than the hearts of cold blooded animals; e.g., the frog's heart beats about 20 times a minute, whilst the mouse's heart beats from 500-1,00o times a minute. These high speeds obviously necessitate a very careful timing of the contractions of the different portions of the heart. This is achieved by the specialisation of certain tissues which conduct the impulses from chamber to chamber. These are shown in fig. 4. The remnant of the sinus venosus situated in the right auricle around the great veins is the pace-maker of the mammalian heart, and from here the impulse spreads all over the two auricles at a rate of about 4oin. a second, which is so times the rate of the conduction in the frog's heart. The auricles are of course firmly attached to the ventricles, but there is only one small bridge of tissue that is capable of carrying the wave of excitation from the auricles to the ventricle. This bridge is called the Bundle of His and consists of specialised muscle fibres called Purkinje fibres. The exact arrangement of the Bundle of His in birds is not well known, but in mammals it is a well defined bundle that first splits into two divisions which pass to the two ventricles and then branches out into a network of fibres covering the interior of the ventricles. At the commencement of the Purkinje system is a mass of small muscle cells called the auriculo-ventricular node and here the wave of excitation is checked for a fraction of a second (in man for about one-twentieth of a second), and then the contrac tion wave is carried rapidly down the Purkinje system so that it reaches all portions of the ventricle at almost the same instant.This is an arrangement which allows sufficient time for the blood to move from auricle to ventricle when the auricle contracts and at the same time ensures that the whole ventricle shall contract simultaneously. The high efficiency of the mammalian heart prob ably depends very largely on this peculiar timing mechanism. The remarkable adaptability of the heart as a pump is illustrated by the fact that all mammalian hearts are built on the same type, but the heart of a small mouse weighs about 0.15 grams whereas the hearts of the largest whales weigh about 200 kilos. Moreover there are huge variations in speed for the heart of the mouse can beat 1,000 times a minute whilst the heart of the horse beats only 3o times a minute. These examples show over what an extraordi nary range of size and speed the mammalian heart is capable of functioning efficiently.

The Capacity of the Vertebrate Heart for Work.

An out standing feature of the heart as a machine is its capacity to per form continuous work, for it beats continuously during the life of the body. In the case of the human heart, this contracts i oo,000 times a day and the left ventricle daily expels some 10,000 litres of blood working against a resistance of 1 20mm. of mercury. Another remarkable feature is the reserve power of the heart. The work that the heart does during bodily rest is only a fraction of the work it can do. The power of the body to perform long continued muscular exercise is limited by the amount of oxygen per minute that can be supplied to the muscles, and this again depends on the quantity of blood that the heart can expel per min ute. The heart of a human athlete during violent exercise can expel three times as much blood per minute as it expels during bodily rest, but to perform this work the heart itself requires about one quarter of the blood it expels, for the heart's oxygen consumption during such violent exercise is nearly equal to the oxygen usage of the whole body when at rest. Athletic animals capable of feats of endurance such as the dog, the horse, the hare or man are characterized by having large hearts with great reserve powers. On the other hand animals which never need to perform continuous exertion have relatively small hearts with low reserve powers. The rabbit and hare form a striking contrast. The rab bit's heart weighs 2.7 parts per 1,000 parts of body weight, whilst the hare's heart weighs 7.5 parts per 1,000. Corresponding to this difference in weight the rabbit's pulse rate at rest is 205 which is about two-thirds of the maximum rate at which it can work, whereas the hare's pulse rate at rest is only 64 which is less than one quarter of its maximum rate.Since the maximum output of the heart is greatly in excess of its normal output, it obviously requires some controlling mechanism to adjust its work to the bodily needs. This adjustment is partly effected by variations in the venous filling of the heart, for the heart muscle is so adjusted that the more complete the filling the more powerful the contraction. In addition the heart is controlled by two nerves, the vagus nerve which reduces the heart's fre quency, and the sympathetic nerve which augments the frequency and the force of the beat. Augmentor and depressor nerves of this type are present in most invertebrate hearts and in all verte brate hearts, but their activity is most marked in the case of athletic animals. For example cutting the vagus nerves increases the frequency of the hare's heart from 64 to 264 beats per minute, whereas cutting the vagus nerves in the rabbit only increases the frequency from 205 to 321 beats per minute.

Although the mammalian heart is a very efficient pump, yet there is a limit to the amount of work that can be done per minute by a given weight of muscle. The actual limiting fact is probably the maximum amount of blood, and consequently the maximum amount of oxygen, that can be supplied to the heart muscle per minute by the arteries of the heart (the coronary arteries). The oxygen required per unit weight by warm blooded animals varies inversely as the cube root of their body weight, and hence small animals require much more oxygen per unit weight than do large animals. For example the ox needs about 3.5cc. of oxygen per minute per kilo. of body weight, whilst the mouse needs 17 times this quantity.

It is a striking fact that a very large number of species of birds and mammals weigh between 10 and 3o grams but very few weigh less than i o grams. A probable reason for this fact is that the oxygen requirements per unit weight in the case of animals of 10 grams is so great that the heart has to do work at a rate that approaches the maximum possible capacity of heart muscle. See A. J. Clark, Comparative Physiology of the Heart (1927), also