Coniferales

CONIFERALES General.—The plants included in this, the largest and most im portant, division of Gymnosperms are a less homogeneous assem blage of forms than the cycads, and include approximately 46 genera with about 47o species. While the cycads are all included in a single family of two tribes, the conifers may be conveniently distributed among five families, which agree, generally, in the fol lowing characters :—They are copiously branched trees or shrubs, frequently of pyramidal form (as illustrated by the conventional "Christmas tree"—invariably a conifer). The leaves are always simple, and small compared with the size of the plant, usually linear, or short and scale-like, and generally persisting for more than one year. The plants are monoecious, e.g., Pinus, or dioe cious, e.g., Juniperus, Taxus, and the cones are never terminal on the main stem. There is no perianth. The very regular monopodial branching is, perhaps, the most striking character of the majority of the conifers, of which a good example is seen in the giant Cali fornian redwood, Sequoia (Wellingtonia) gigantea, the largest of the Gymnosperms, often seen in cultivation. Other conifers of this typical habit are many pines and firs, the monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria imbricate), the Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria ex celsa) , and the cedars and larches, several species exceeding i 5of t. in height. The yews and junipers and some other conifers grow as bushes, which in place of a main mast-like stem possess several repeatedly branched leading shoots. Dwarf forms are sometimes met with under arctic, alpine or other unfavourable conditions. Probably the smallest of these dwarf conifers is Dacrydium laxi folium, found on New Zealand moors, which may bear seed when only tin. high. Artificially dwarfed specimens of some species are commonly cultivated by the Japanese.

Leaves.

Nearly all conifers are evergreen and retain their leaves for from three to ten years; the larch (Larix), however, sheds its leaves each autumn, and those of the Chinese larch dolarix Kaernpferi), which is also deciduous, turn a bright yellow before falling. In the swamp cypress (Taxodiuyn distichum) the tree assumes a rich brown colour in the autumn, and sheds its leaves with the branchlets which bear them. Deciduous branches occur also in some other species. The leaves of conifers are usually characterized by their small size, e.g., the needle form represented by Pinus, Cedrus, Larix, etc., the linear flat or angular leaves, appressed to the branches, of Thuja, Cupressus, Libocedrus, etc.; all of which have a single median vein. The flat and comparatively broad leaves of Araucaria bricate, A. Bidwillii, and a few species of the southern genus docarpus, are traversed by eral parallel veins, as are the still larger leaves of Agathis, which may reach a length of several inches. In addition to the foliage leaves several genera also possess scale leaves of various kinds, resented by bud-scales in Pinus, Picea, etc., which frequently sist for a time at the base of a young shoot which has pushed its way through the yielding cap of protecting scales, while in some conifers the bud-scales adhere gether, and after being torn near the base are carried up by the growing axis as a thin brown cap. The cypresses, Araucarias and some other conifers, have no true bud-scales ; in some species, e.g., Araucaria Bidwillii, the rence of small foliage leaves, which have functioned as scales, at intervals on the shoots, affords a measure of seasonal growth. The occurrence of long and short shoots is a characteristic feature of pines, cedars and larches. In Pinus the needles occur in pairs, or in clusters of three or five at the apex of small and inconspicuous short shoots of limited growth (spurs). The spur is enclosed at its base by a few scale leaves, and is borne on a branch of unlimited growth in the axil of a scale leaf. In some junipers, cypresses, etc., in which small leaves appressed to the stem are normal in adult plants, examples occur in which these leaves are replaced by the slender needle-like leaves. standing out more or less at right angles to the branch, which are characteristic of the seedling stage. Such cases are often seen in cultivation, and are usually named "Retinospora," though this name does not denote a true genus, but merely the persistent juvenile forms of Tjiu ja, Juniperus, Cupressus, and other trees of the same type.A remarkable and unique leaf is found in the umbrella pine (Sciadopitys verticillata). These leaves are produced singly on whorls of spur shoots and bear traces, in the grooved surface and in the possession of two separate veins, of an origin from pairs of needle leaves. A peculiarity of these leaves is the inverse orientation of the vascular tissue ; each of the two veins has its phloem next the upper, and the xylem to wards the lower, surface of the leaf ; this unusual position of the xylem and phloem is explained by regarding the needle of Scia dopitys as composed of a pair of leaves on a short shoot, fused by their upper margins (fig. 12). The short shoots of the cedar and larch are stouter structures bearing an in definite number of leaves, and are not shed with the leaves as are the spurs of pines and Sciadopitys. In the genus Phyllocladus (New Zealand, etc.) there are no green foliage leaves, but in their place flattened branches (phylloclades) borne in the axils of small scale leaves. The cotyledons are usually two in number in conifers, but occasionally more, as in cedars and pines, reaching as many as 15 in the last named.

Cones.

A typical "male': cone consists of a central axis bearing from less than a dozen to a very large number of sporophylls which usually follow the leaf arrangement, i.e., they are generally spirally arranged except in most of the Cupressaceae where they are opposite or whorled. The sporophyll (fig. 13) is composed of a slender stalk, terminating in a knob or scale and bearing from two to 15 pollen-sacs on its lower surface. The larger number of sporangia (6 to 15) are characteristic of Araucaria (fig. 13) and Agathis in which the sporangia are also peculiar in their large size and in being long, narrow and free. They may thus be com pared to the sporangia of the horse-tails (Equisetum). In the yew (Taxus) the stalk is attached to the centre of a large more or less circular expansion bearing four to eight pollen-sacs on its inner surface, but which are also fused with the stalk, not hanging freely like those of Araucaria. The sporangia usually open by a longitudinal, occasionally by a transverse, slit.The structure of the "female" cone differs considerably in the five families of conifers which are as follows :— In the first family—Araucariaceae—the female cone, especially when young, has often a close resemblance to the male, and may be interpreted as homologous with it. On this view it is regarded as an axis bearing a large number of sporophylls, closely packed and spirally arranged. Each sporophyll consists of a scale-like basal part and a terminal up-turned leafy part—the lamina. Em bedded in the scale with its apex facing the cone axis is a single large ovule. The nucellus is long and narrow and projects beyond the micropyle. In Araucaria (but not in Agathis) a ligule projects from the upper surface of the scale beyond the base of the ovule.

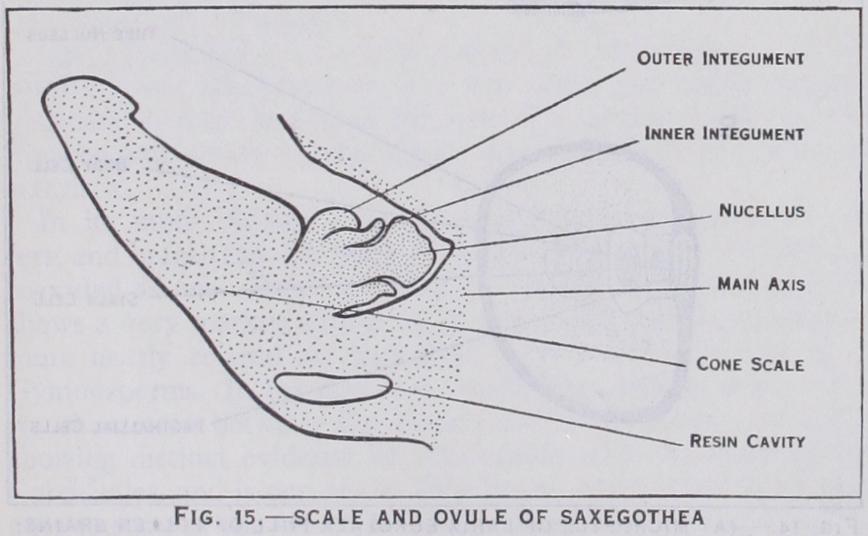

In the Podocarpaceae the cone is often much reduced, ranging from an axis with a small number of sporophylls, each bearing an inverted ovule, as in Microcachrys, Saxegothea (fig. i5), and some species of Dacrydium, to the form found in other species of Da crydium and in Podocarpus, where the number of fertile scales is reduced to two or one, small in comparison with the large inverted ovules. In the latter case, broadly speaking, the cone practically consists eventually of one or two naked ovules, though traces of the subtending scales can always be found. Phyllocladus and Pher osphaera are exceptional in having erect (not inverted) ovules. The ovules of the Podocarpaceae usually have a second, outer, integument, the epimatium, wholly or partially enclosing the inner (fig. The female cones of the third family, Pinaceae, are better known, but much more difficult to interpret. To this family most of the common northern conifers belong, such as the pines, spruces, silver firs, cedars and larches. The last-named will serve as a type. Here the cone consists of an axis bearing a large number of closely set, spirally arranged pairs of scales. Of the two scales in each pair one is immediately above the other (i.e., in its axil), the lower being bract-like and sterile and known as the carpellary scale or bract scale, the upper bearing the ovules (usually two) on its upper surface and being known therefore as the ovuliferous scale. The small ovules are fused to the surface of the scale at its proximal end, and lie with their micropyles facing the axis. In the very young cone the two sorts of scales are of similar size; after pollination the ovuliferous scale grows considerably,, and is always thicker than the subtending bract scale. The latter, in the larch, at first grows in length faster than the former and so pro jects beyond the ovuliferous scale in the older cone, but in most cases the bract scales either remain quite abortive after pollina tion, as in the pine, or grow much more slowly than the ovuliferous scales, the latter alone showing on the outside of the cone. In both cases the scales fuse together externally after pollination, forming a continuous outer covering to the cone and effectually enclosing the ovules, which remain hidden until after the seeds are ripe, often for one, two or more years.

It is not possible to explain here the various views which have been held as to the nature of the ovuliferous scale (the bract scale is clearly homologous with a subtending leaf) but that which has been most generally accepted was due, in the first place, to Alexander Braun in 1842. He explained the ovuliferous scale as representing the two leaves of a spur shoot, fused (as in the double needle of Sciadopitys), by their posterior (adaxial) margins. The usual two ovules would thus be borne one on each leaf (sporo phyll), as in the preceding families. This explanation also takes account of the inverted vascular supply of the ovuliferous scale, again paralleled in the leaf of Sciadopitys (fig. I2). In abnormal cones the ovuliferous scale is sometimes replaced by a dwarf shoot bearing two leaves, which lends further support to Braun's hypothesis.

In the next family, Cupressaceae, the more typical genera appear to have only one kind of scale, while others, belonging to the tribe Taxodioideae, often have a ligule-like structure on the upper surface of the scale (e.g., Cunninghamia). The ovules are borne close to the base of the scale, and are usually erect, less commonly inverted. The number borne on one scale is very vari able, but from three to seven is usual. Anatomical examination of the scale, however, always indicates the presence of two sets of vascular strands of which the upper is inverted; of which the most obvious explanation is that the cone scale represents the bract and ovuliferous scales of the Piriaceae partially or wholly fused together. There are certain difficulties in this apparently simple explanation, but nevertheless it is a generally accepted view.

In the last family, Taxaceae, the female cone is an even more reduced structure than in the Podocarpaceae, consisting usually of a very short axis bearing few or many scale leaves at its base and apparently terminating in a single erect ovule. In reality the apparently terminal ovule may be in the axil of one of the upper most scales. The whole structure is so reduced that it is difficult, and perhaps unprofitable, to explain it in terms of the other four families, but at least it gives little indication of the complexity characteristic of Pinaceae and Cupressaceae. Unlike cycads, Ginkgo and the majority of other conifers the ovule has two in teguments, the outer more or less fleshy, as in the red "aril" of the yew seed.

Fertilization and

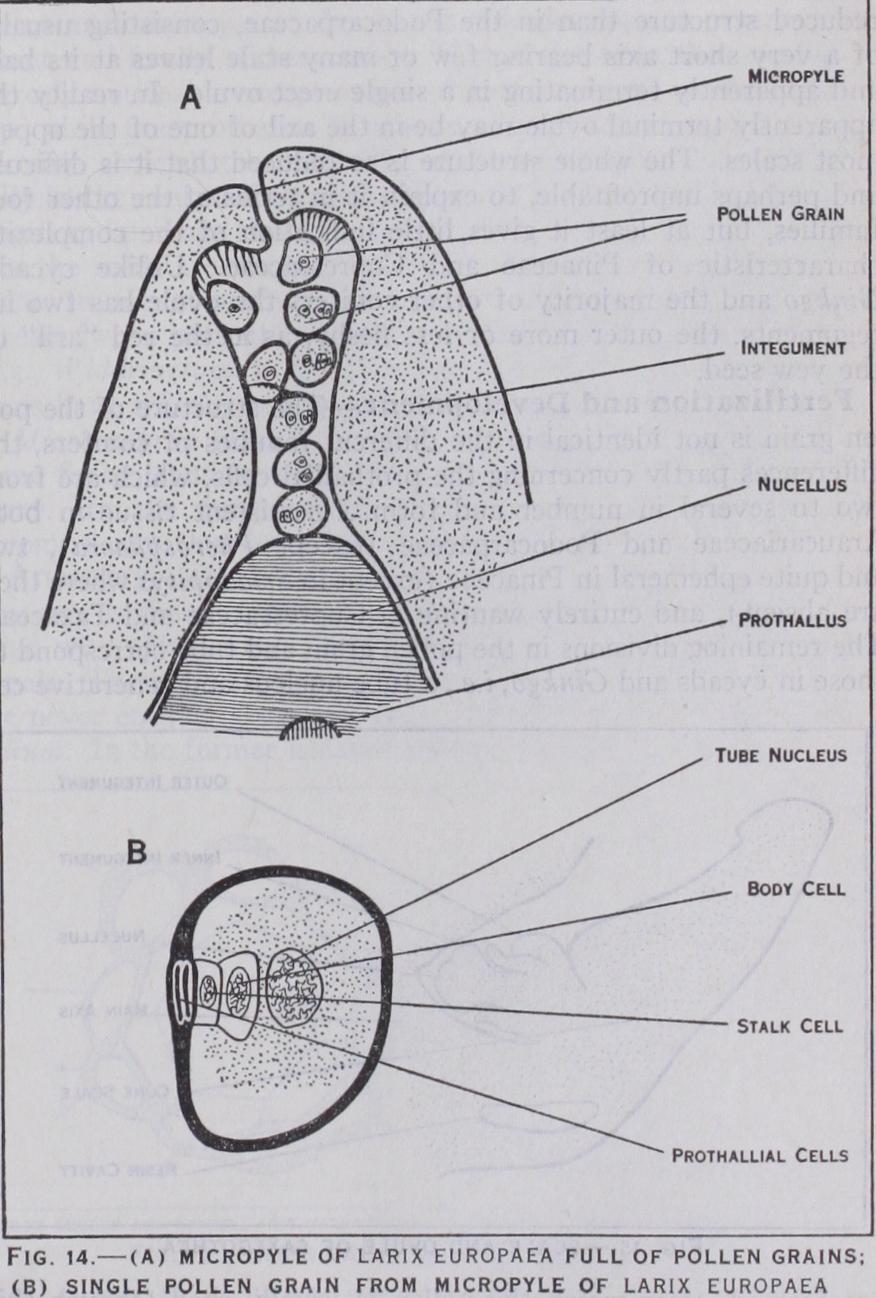

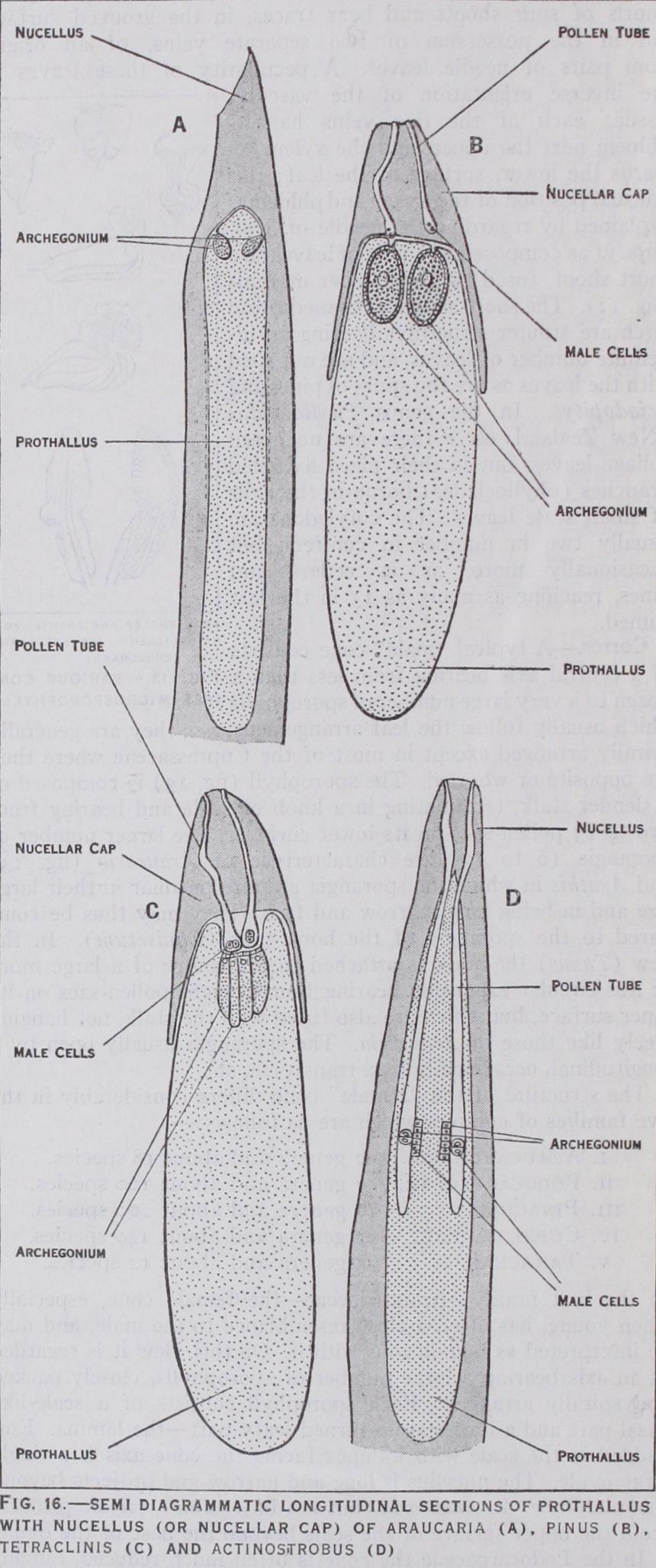

structure of the pol len grain is not identical in the different families of conifers, the differences partly concerning the prothallial cells, which are from two to several in number and form a persistent tissue in both Araucariaceae and Podocarpaceae (except Pherosphaera), two and quite ephemeral in Pinaceae (except in Sciadopitys where they are absent), and entirely wanting in Cupressaceae and Taxaceae. The remaining divisions in the pollen grain and tube correspond to those in cycads and Ginkgo, i.e., a tube nucleus and generative cell are formed, after which the pollen is usually shed (though this may happen before these cells are differentiated as in Widdring tonia or after the division of the generative cell to form stalk and body cells as in Larix and most Pinaceae [fig. 14] ). The pol len is carried by the wind to the neighbourhood of the ovule. In Araucariaceae it germinates on the scales of the female cone, the tube eventually growing into the nucellus; in Saxegothea (Podo carpaceae) it germinates on the stigma-like apex of the nucellus (fig. i 5), and in most other conifers it is caught in the pollination drop which is extruded from the open micropyle of the young ovule and on evaporation of which the pollen is drawn down to the apex of the nucellus. The pollen tube at once begins to grow into the nucellus, but downwards, towards the prothallus, not lat erally as in cycads, and into the tube pass, not only the tube nucleus but also, in all cases, the stalk nucleus and body cell. No well organized pollen chamber is formed in the nucellus of coni fers, but sometimes a few cells at its upper end break down and so produce a saucer-shaped depression (fig. 16). The body cell divides to form two non-motile male cells, which in Cupressaceae are exactly equal and both functional, but in the other families are usually unequal, and only the larger functional.

In the young ovule a single functional megaspore develops, usually the lowest of a row of three or four, formed from a mother-cell as in cycads and practically all other seed plants. Ex ceptionally, as in Taxus, Callitris and Pherosphaera, two or more megaspores may begin to develop. The formation of the prothallus takes place almost exactly as in cycads, but it is smaller, usually much smaller, in the conifers, as are also the archegonia. The latter are few, and formed (as in cycads) from separate superficial cells at the apex in Podocarpaceae (except Pherosphaera and Microcachrys), Pinaceae and Taxaceae (fig. 16) ; rather more numerous and more scattered, and more or less lateral, in Phero sphaera and in Araucariaceae (fig. 16), and in a single apical complex of 6 to 24 (all in contact with other archegonia of the group) in Microcachrys and in most Cupressaceae (fig. 16). In the remaining Cupressaceae, including Sequoia and the tribe Calli troideae, the archegonia are very small and numerous, usually deep-seated, and arranged in from one to several groups (in con tact with each other in any one group) placed laterally along the prothallus, and never at, or very close to, the apex, which is usually pointed (fig. 16). The number of such archegonia may be up to about 6o in Sequoia or as many as ioo in Widdringtonia. A curious feature of these forms is that the size of the egg nucleus is about the same as that of the male nucleus at the time of ferti lization, and in Actinostrobus (fig. 16) even the whole arche gonium may be no larger than the male cell, so that we have here what practically amounts to a case of isogamy, of which no other example can be found in any plant of higher organization than the Algae and Fungi. It should be noted that in all conifers, in marked contrast with the preceding divisions, the male cells possess no cilia, and are carried by the growth of the pollen tube either into the archegonium itself or to a point very close to it. It is usual to describe the male cells as non-motile, but it is not clear that this is always strictly accurate as they may pass from the tube into the archegonium without being actually carried into it, which seems to imply some limited power of independent movement, possibly of an amoeboid nature. In the Araucariaceae, as in Sequoia and the Callitroideae, male and female nuclei are equal in size at the time of fertilization. In most other conifers the male nucleus is distinctly smaller than the female, while in the family Pinaceae it is only about one-hundredth of the volume of the female nucleus.

In conifers the neck of the archegonium is always composed of more cells than the two characteristic of cycads, but the actual number varies widely, from about four in one tier to about a dozen or more in several tiers. Speaking generally it is less con spicuous in the Cupressaceae than in the other families.

The early development of the embryo varies a good deal in the different families. In Araucaria and Agathis 32 or more free nuclei are formed in the protoplasm of the archegonium. These nuclei then arrange themselves into a central group (of two tiers) and a peripheral enveloping layer, after which walls are laid down between them. The structure thus formed is the proembryo and completely fills the archegonium. The central group alone forms the embryo, the basal cells of the peripheral layer functioning as a protective cap while the cells nearest the neck elongate to form a suspensor.

The case of the Pinaceae is best known. Here only four free nuclei are formed which pass to the base of the archegonium and there divide to form a basal layer of four cells and an upper tier of four nuclei. The latter repeat the process, resulting in two layers of cells and one of four nuclei above. Lastly the cells of the lowest tier divide once more giving three tiers of four cells each with one above of four nuclei. This is the structure of the proembryo and it occupies approximately the basal one-third or one-quarter of the archegonium. The tier of nuclei has no obvious function, the next tier may serve to prevent the suspensor cells growing back into the archegonial cavity, the lowest tier but one elongates enormously, forming the suspensor, while the basal tier forms the true embryo. The latter eventually becomes differ entiated into a hypocotyl terminating in a radicle at the sus pensor end and a whorl of, usually, several cotyledons at the other end, surrounding a central plumule. It sometimes happens that the four suspensor cells become separated from one another, along with the corresponding embryo cells, the latter then forming four separate embryos instead of one, though in any case not more than one embryo in a prothallus normally reaches maturity.

In the Podocarpaceae and in the more typical Cupressaceae (excluding Sequoia and the Callitroideae) proembryo development is similar to that in Pinaceae except that eight free nuclei are formed before cell formation and that the tiers are much less regu lar both in number and arrangement, the basal often consisting of only a single cell ; and the embryo has usually only two coty ledons. In both cases the proembryo only occupies the basal part of the archegonium. The family Taxaceae only differs from the two preceding in the fact that the proembryo fills the arche gonium, with the exception that the genus Ceplialotaxus develops a protective cap like that of Araucarians.

In Sequoia and the Callitroideae cell formation takes place earlier than in any other forms (in Sequoia at the first division) and the proembryo fills the archegonium. The embryo develops from a single cell which may be that at the base of the arche gonium (Sequoia) or may be cut off, at the end facing the base of the prothallus, from any of the lower cells of the proembryo (Actinostrobus). In either case the larger cell adjacent to the embryo cell becomes the suspensor.

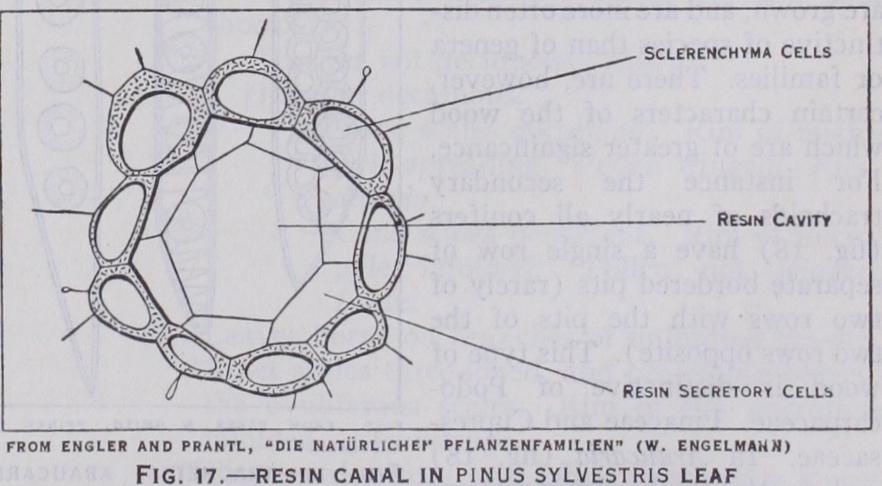

In spite of these marked differences in the early embryo devel opment there is a considerable uniformity in the structure of the seed in conifers. In most cases the testa ripens dry and woody, as the outer fleshy layer of the cycads only develops to a very small extent and finally withers away. Within the testa the nucellus is scarcely noticeable except as the withered remains of the nucellar cap, while the prothallus is always packed full of starch and so becomes somewhat brittle. The embryo normally lies symmetri cally in the centre of the prothallus and is about two-thirds of its length and perhaps about one-tenth of its volume. In several coni fers the seeds are winged, but while the wing is formed, in Pin aceae, from part of the tissue of the ovuliferous scale, in Cupres saceae (when present) it is part of the integument of the ovule (e.g., Widdringtonia). In Taxaceae and some Podocarpaceae the seeds have a fleshy covering, not always of the same nature, and in Microcachrys (Podocarpaceae) the cone scales themselves be come fleshy, thus forming a "fruit" something like a small rasp berry. In the juniper also (Cupressaceae) the fertile scales become fleshy, thus forming a berry-like "fruit." Anatomy.—One of the most striking features of conifer anatomy is the occurrence of long cylindrical intercellular spaces lined with thin-walled, resin-secreting cells and known as resin canals. These are frequently present in all parts of the plant and are never entirely absent except in Taxus and in Dacrydium laxi folium. In the former isolated resin-secreting cells occur here and there in the tissues, but in the latter even these appear to be lack ing. The resin canals are most frequently found in the cortex and have a characteristic structure, the epithelial cells which secrete the resin being in turn surrounded, as a rule, by a ring of much more conspicuous thick walled protecting cells (fig. i 7). In many genera resin canals are also found in the wood, as in Pinus, while sometimes they are restricted to the cone axis, as in Sequoia. They are nearly always present in the leaves, often below the vas cular bundle. Although resin canals are a characteristic feature of the conifers they are by no means peculiar to them, being equally distinctive of some tropical families of flowering plants (e.g., Anacardiaceae) and occasional plants outside those families such as sunflower and ivy.

The phloem always includes sieve tubes without associated com panion cells (though phloem-parenchyma cells with albuminous contents are present, and with pitted areas chiefly on their lateral walls). In the Pinaceae the phloem consists solely of sieve tubes and phloem parenchyma, but in most other forms concentric cylinders of bast fibres occur in regular alternation with the func tional phloem.

Coniferous wood is homogeneous in structure, consisting almost entirely of tracheids with circular (rarely polygonal) bordered pits on the radial walls. Xylem parenchyma is never abundant, but traces of it are present in many genera. In Pinus there is no wood parenchyma except in association with the numerous resin canals scattered through the wood. The medullary rays consist of a single layer of cells except in certain Pinaceae (where some of them are f usif orm in section, enclosing a single horizontal resin canal) and have usually a complex structure. The margins, both upper and lower, of that part of the ray which lies in the xylem, are often composed of horizontally elongated tracheids with irregularly folded walls and bordered pits, while the central rows of cells are parenchymatous and thin-walled, but usually pitted. In the phloem the marginal ray tracheids are replaced by irregularly lobed albuminous cells.

Root.

The roots of many conifers possess a narrow band of primary tracheids with a group of slender protoxylem elements along either margin (diarch). In other cases the primary xylem is triarch or tetrarch (Sequoia) or even polyarch. An old root ap proximates closely to a stem in structure, but the annual rings are often less clearly marked and the tracheids larger and thinner walled. The primary tissues are, of course, differently arranged, but are apt to become obliterated with age.

Stem.

The primary vascular bundles in a young conifer stem are collateral, and, like those of a Dicotyledon, they are arranged in a circle round a central pith and enclosed by a common endo dermis. Secondary thickening begins at an early stage and con tinues throughout the life of the plant with seasonal variations and interruptions resulting in the normal appearance of clearly defined annual rings, as in most woody Dicotyledons. The dif ferences of structure met with in conifer stems are sometimes affected by the conditions (in cluding climate) under which they are grown, and are more often dis tinctive of species than of genera or families. There are, however, certain characters of the wood which are of greater significance.For instance the secondary tracheids of nearly all conifers (fig. 18) have a single row of separate bordered pits (rarely of two rows with the pits of the two rows opposite). This type of wood is distinctive of Podo carpaceae. Pinaceae and Cupres saceae. In Araucaria (fig. 18 ) and Agathis the bordered pits are in one, two or three rows on the radial walls and, being in contact, are polygonal in shape, and the pits of adjacent rows are alter nate and not opposite. In Taxus (fig. 18) the normal type of bor dered pit occurs, but in addition conspicuous spiral thickening bands are met with. It is doubtless these which give to the wood of the yew its well-known strength and elasticity, recognized by the mediaeval English when they used it for their bows, which were the most efficient weapons of that period.

Leaf.

The cotyledons have each a single vascular strand ex cept in Podocarpus, which has two, and in Araucarians where there are four or more. In the latter there are also several resin canals, one or two of which are also found in Pinus, though absent in most other forms. The adult leaves (fig. 20) have a single median vein except in Agathis, several species of Araucaria (fig. 20 C) and a few of Podocarpus, which have several parallel veins. In some pines (e.g., Pineus and Abies [fig. 20]) this vein includes two vascular bundles, but in others, and in all Cupressaceae (fig. 20) and Taxa ceae and in all podocarps, except the few species of Podocarpus al ready mentioned, there is only a single vascular strand. In all cases the leaf trace leaves the central cylinder as a single strand, unlike Ginkgo and the cycads, but in Araucaria, etc., this strand splits into several in its passage through the cortex. In most gen era one or more resin canals are found in the leaf, and another equally distinctive feature is the presence, generally on the flanks of the vascular strand, of a few isodiametric tracheids known as "transfusion tracheids." Sometimes there are also horizontally elongated transfusion tracheids extending towards the leaf margin. A noteworthy feature is the common occurrence of hypodermal fibres, but their presence and extent is partly dependent on the light conditions under which their development takes place; e.g., a pine needle grown in continuous light lacks the usual hypodermal fibres, as well as differing in some other details. In Pinus and Cedrus the homogeneous mesophyll is characterized by the in folding of the cell walls. In many leaves, such as those of Abies (fig. 20) and Larix there is both palisade and spongy par enchyma. In Araucaria imbricate (fig. 20) a palisade layer occurs in both upper and lower parts of the mesophyll, and resin canals are found between the veins, while in the multi-nerved species of Podocarpus (section Nageia) a canal occurs below each vein. This position (below the vein) is that usual for the single resin canal of many forms (fig. 2o), while in Larix, Abies, etc., two canals run through the leaf parallel to the margins (fig. 20). Each stoma is normally sunk at the base of a pit (fig. 19), and the stomata are frequently arranged in rows, their position being marked by two or more bands of wax on the surface of the living leaf.

Geographical Distribution.

Most conifers grow in forests, either alone or mixed with angiospermous trees, forming one of the characteristic features of the vegetation in temperate and alpine regions. Since a large proportion of the cold temperate lands lies in the northern hemisphere it is easy to understand why the chief home of the Coniferales is in the north, where certain species occasionally extend into the arctic circle and beyond the tree limit, e.g., Juniperus none. The tree limit in northern Europe is chiefly marked by conifers (Picea, Larix, Abies, etc.), and many are abundant in North America, such as Juniperus virginiana, Taxodium and several pines on the eastern side; Pseudotsuga, Sequoia, other pines, etc., on the west ; while Picea, Larix, Abies, Tsuga, Taxus and Pinus strobus are characteristic forms throughout. In the Mediterranean region occur Pinus mari tima, P. piney and other species, cedars and cypresses. In Japan and China are a number of small endemic genera such as Cryp tomeria, Cunninghamia, Sciadopitys, Cephalotaxus and Pseudo larix. In the Himalayas are Cedrus, Taxus and endemic species of Abies, Pinus, etc. Apart from high altitudes few conifers are found in the tropics, but various endemic types are met with in the south, of which Podocarpus is most widely distributed, while IViddringtonia is peculiar to South Africa and a considerable num ber of characteristic genera are found in Australasia, such as Callitris, Agathis, Dacrydium, Microcachrys, Athrotaxis and Araucania, most of which are endemic. The last named, however, occurs in South America as well, where Fitzroya and Saxegothea are also met with, chiefly in the Andes.