Cycadales

CYCADALES General.—This division in cludes nine genera and over 8o species. It consists of plants with tuberous or columnar stems, seldom branched, often clothed with an armour of petiole bases as in the stems of ferns, and terminating in a crown of large pinnate leaves (bi-pinnate in one genus). The plants are dioecious, with the cones always compact, with numer ous sporophylls spirally arranged on an axis, except in female plants of Cycas, which bear on the main stem a loose rosette of leaf-like sporophylls each bearing from 2 to 6 or 8 ovules.

The cycads are practically confined to tropical and subtropical regions and are fairly equally divided both between northern and while Microcycas and Stangeria occur only in West Cuba and South Africa respectively.

Externally some of the larger cycads closely resemble palms, others having an equally close resemblance to tree ferns, while so closely do the smaller species approximate to ferns in appear ance (when not in cone) that Stangeria was actually first described (by Kunze in 1835) as a species of the fern Lomaria.

Cycads are characteristically very long lived and slow growing and certainly reach an age of upwards of a thousand years, probably much more.

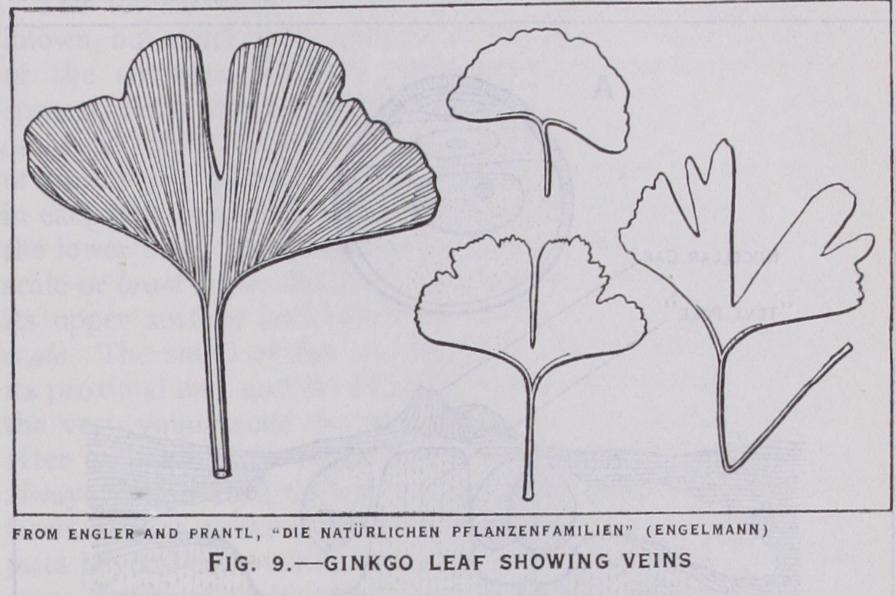

The armour of dead leaf bases found on the old stem (fig. 1) is more larly characteristic of the columnar forms, and is not found in Bowenia and genie. In the tuberous forms the stem is usually more or less subterranean, but may be very sive, like a gigantic carrot. The leaves of Cycas consist of a long rachis bearing numerous linear leaflets, each with a single midrib and no other veins. When young these leaflets are coiled up like the leaves of a fern. In most other cycads the leaves are similar except that the leaflets contain a number of parallel veins, e.g.

Dioon and Encephalartos. Stangeria has only a few leaflets on the rachis and each is traversed by a midrib from which simple or forked veins pass off at a wide angle. The leaves of Bowenia differ from those of other genera in being bi-pinnate (fig. 2) . It is only in Cycas that the young leaflets are conspicuously coiled, the remaining genera showing little or no trace of this character. In Macrozamia heteromera the narrow pinnae are dichotomously branched almost to the base (fig. 3) . In some forms, such as most of the species of Encephalartos, the margins of the leaflets are spinous. In Ceratozamia the broad petiole base is characterized by the presence of two lateral spinous processes suggestive of stipules, and comparable with the stipules of Marattiaceous ferns.

Cones.

The "male" (or microsporangiate) cones of cycads (fig. 4) are very uniform in structure, and from one to a hundred may be produced in one season. Each consists of an axis bearing crowded, spirally disposed sporophylls, which are often wedge shaped and angular, while in other cases they consist of a short, thick stalk terminating in a peltate expansion or prolonged up wards in the form of a triangular lamina (fig. 5) . The crowded sporangia (pollen-sacs) are found on the lower side of the sporo phyll and are often arranged in more or less definite groups (or "sori") . The sporangia break open when ripe by a slit radiating from the centre of the sorus. The sporangia are large, not unlike those of Angiopteris (a Marattiaceous fern) and their walls are several layers of cells in thickness. Each sporangium contains several oval spores which develop into pollen grains before they are set free. In this process each spore cuts off a small but per sistent "prothallial cell," and immediately divides again to cut off an almost equally small "generative cell," the remaining nucleus, occupying the larger part of the spore cavity, being the "tube nucleus." In this 3-celled condition the pollen is shed.The female plants bear cones which in most genera occur singly in the centre of the crown, but in Encephalartos, Bowenia and Macrozamia from two to several may be found. In some cases these female cones reach an enormous size, that of Encephalartos Gaffer being up to a yard in length and weighing as much as ioolb., while that of Macrozamia Denison may be as long, though its weight seldom exceeds 6olb. The smallest cones are those of Zamia, that of Zamia pygmaea being sometimes less than 3cm. in length. The sporophylls usually have some, often a close, resemblance to those of the male cone, and are clearly homol ogous with them.

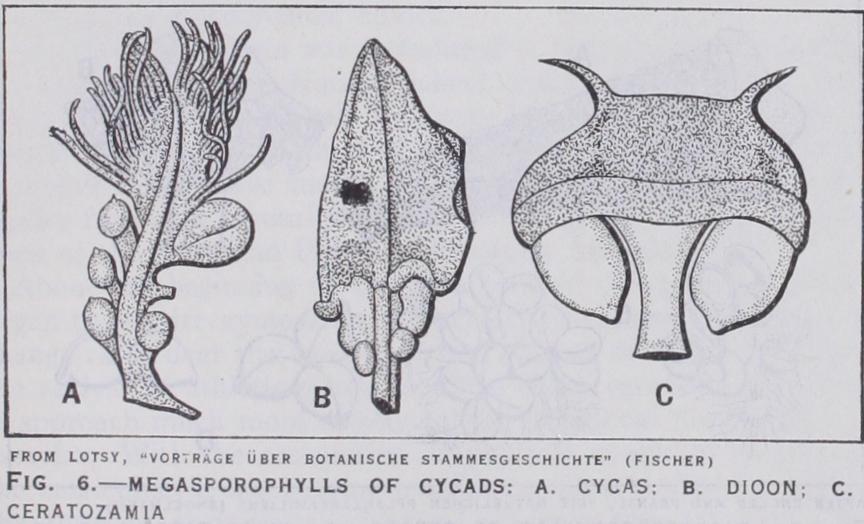

The most primitive type is evidently Cycas, in which the sporo phylls are arranged round the apex like a crown of foliage leaves and are definitely leaf-like in form. In C. revoluta and C. cir cinalis each may produce several laterally attached ovules, but in C. Normanbyana the sporophylls are shorter and the ovules are reduced to two. In all other genera the cone is a much more definite and compact structure, but the sporophylls of Dioon and Stangeria terminate in a leaf-like up-turned process, and are clearly comparable with those of Cycas. In some of the remaining genera the sporophylls are shorter with thick peltate heads, and each bears two ovules on the lower surface (fig. 6). The young ovule consists of a spherical or ovoid rather massive nucellus, sur rounded by the integument. The small round opening at the apex of the integument is known as the micropyle.

Fertilization and Development.

The pollen is carried by the wind, or very rarely, perhaps, by small beetles or other insects, to the micropyle and lodges there. Meanwhile the tip of the nucellus projects into the base of the micropyle in the form of a tiny beak, at the exact tip of which a fine hole appears, becoming somewhat wider below. This narrow but relatively deep hole, the "pollen chamber," being exactly below the centre of the micropyle, the pollen grains pass into it (or, in some cases at least, are into it by the evaporation of a drop of liquid which oozes out from the micropyle at the time of pollination, as in conifers) and the tip of the pollen chamber, as well as the micropyle, closes and hardens, thus completely enclosing the pollen grains, of which from half a dozen to a dozen are usually found here. Later these develop pollen tubes as described below.While these changes are going on, a large cell, the megaspore, makes its appearance in the central region of the nucellus, rapidly increases in size, and ultimately absorbs the greater part of the nucellus. Its nucleus divides re peatedly and cells are produced from the peripheral region in wards, which eventually fill the spore cavity with a homogeneous tissue, the prothallus. From one to ten separate superficial cells at the apex of the prothallus now increase in size. Each cuts off a small cell at the top, which divides to form the small two celled neck of the archegonium, the lower cell enlarging rapidly and becoming the egg-cell, its nucleus cutting off another small nucleus (which soon disappears) just before fertilization (fig. 7) .

In Microcycas a very large number of archegonia (up to 200 exceptionally) are produced all over the prothallus.

During the development of the prothallus the pollen chamber has enlarged both downwards and outwards, and eventually forms a fairly large chamber open below to the archegonia, which them selves lie at the bottom of a shallow depression in the apex of the prothallus, th; "archegonial chamber." Each pollen grain at once begins to put out a tube which grows laterally into the nucellus just below its outer surface. The apical part of the nucellus is almost the only part remaining by this time, and is known as the "nucellar cap." Close inspection of the outer surface of the nucellar cap reveals several dark lines radiating from the beak outwards for about 2mm. and these mark the positions of the pollen tubes. The "tube nucleus" of the pollen grain passes into, and remains in, the pollen tube, while the pollen grain hangs sus pended by its tube in the pollen chamber (fig. 7) . The "generative cell" divides to form another small sterile cell, the "stalk cell" and a much larger cell the "body cell," which continues to enlarge (as does that part of the tube to which the grain is attached) and finally divides once more into two equal hemispherical cells, in each of which a single very large and actively motile spermatozoid is produced (fig. 8). (In Micro cycas 8 to io body cells and 16 to 20 sperms are formed in each pol len tube.) In the course of the last division two small bodies known as "blepharoplasts" make their appearance just outside the nucleus, and after division is complete one of them remains in each spermatozoid where it gradually gives rise to a spiral band which passes round and round the outside of each sperm while from the outside of the band innumerable fine hair-like cilia are produced which, by their active movements, enable the sperms to swim about, first in the two cells within which they are formed, then in the part of the pollen tube adjacent to the grain after the cell walls break down, and finally in the film of moisture covering the archegonial cham ber, after the bursting of the pollen tube. At last one penetrates the neck cells of an archegonium and so finds its way into the egg cell, where the sperm nucleus slips from its ciliated sheath of protoplasm and swiftly passes down to fuse with the large egg nucleus.

It is noteworthy that cycad sperms are the largest known in either plants or animals, and the only ones big enough to be defi nitely seen under ordinary lighting conditions, and while still liv ing, with the naked eye, the largest of them reaching a diameter of more than a quarter of a millimetre. It is no less remarkable that sperms had been observed repeatedly in every other great group of both plants and animals (excepting Ginkgo) many years before they were ever seen in cycads, although the discovery of motile sperms in Gymnosperms had been predicted nearly 5o years earlier by the great German botanist Hofmeister. They were actually seen for the first time in Cycas in 1896 by a Japanese botanist, S. Ikeno, and shortly afterwards in Zamia by H. J. Web ber, and since that time they have been carefully studied in most of the other genera.

Following fertilization, the fusion nucleus divides repeatedly till from 25o to about i,000 nuclei are scattered through the protoplasm of the archegonium. These nuclei tend to be more closely aggregated at the base, and cell walls first appear in this region, thus forming a tissue at the base of each fertilized arche gonium. An ephemeral tissue may also form throughout the archegonium, as happens in most genera, subsequently breaking down to form cavity, or the centre of the archegonium may become a large vacuole at an earlier stage, as in Cycas. In either case the structure thus formed constitutes the proembryo. A compact group of cells at the extreme base forms the actual embryo, and the cells immediately above these elongate very much and eventually form a very long coiled and tangled suspensor which carries the embryo deep into the prothallus where it grows to about three-quarters of the length of the latter and absorbs about one-quarter of its tissue.

The mature embryo consists of an axis (the hypocotyl) termi nated, at the end next to the suspensor, by a rudimentary root (the radicle) enclosed in a hard covering, the coleorhiza, and bearing a t the other end a pair of large seed leaves or cotyledons, often fused together at their tips, and enclosing between them a minute terminal bud, the plumule. The integument of the ovule has now become the testa of the seed and is differentiated into three layers, an outer, thick, fleshy and brightly coloured one, in the inner part of which several vascular strands run up from the base, a thin hard woody layer, and a very thin inner fleshy layer containing a second set of vascular strands.

Anatomy.

The anatomy of the cycads presents many fea tures of interest. Only a brief reference to one or two of the most striking of these is possible here. The wood is rather soft and laxly arranged and occupies a relatively small part of the thickness of the stem, though the vascular cylinder very slowly increases in thickness in the same manner as in woody Dicotyledons. Some times, as in Cycas, there is a double ring of vascular strands. In connection with the leaves two strands often branch off from the central cylinder on the opposite side to a leaf, pass spirally round in the cortex in opposed directions and pass into the petiole of that leaf, where they break up into a larger number of strands. This arrangement of leaf trace strands is peculiar to cycads, and the strands themselves are often known as girdles. For further ana tomical details reference may be made to The Living Cycads by C. J. Chamberlain.

Classification.

Something has already been said about the characteristic features of certain genera. It will, however, be con venient to conclude with a key to all the genera, and the usual classification of the Cycadales, as follows:— Division CYCADALES. Only family Cycadaceae.Tribe A. Female plant with separate leaf-like sporophylls on the main stem. Leaflet with a midrib only. Cycadeae. Cycas. Tribe B. Sporophylls always in compact cones. Zamieae.

Sub-tribe I. Leaflet with midrib and lateral veins. Stangerieae.

Stangeria.

Sub-tribe II. Leaflet with several parallel veins. Euzamieae.

a. Leaves bi-pinnate. Bowenia.

b. Leaves simply pinnate.

(i.) Megasporophylls (Carpels) with a terminal leafy part. *Ovules on a cushion-like placenta. Dioon.

**Ovules sessile. Encephalartos.

(ii.) Megasporophylls peltate.

*Sporophyll terminating in two horns. Ceratuzamia. **Sporophyll with a spinous projection in the centre. Leaflets usually forked. Macrozamia.

***Megasporophyll flat outside.

tMicrosporophyll not peltate. Microcycas. ff'Microsporophyll peltate like the carpel (fig. 4). Zamia.

Recently some very interesting hybrids have been obtained by crossing various species of Zamia with others of the same genus and with species of Encephalartos and Macrozamia.