Cytoplasmic Inheritance

CYTOPLASMIC INHERITANCE Since the mother contributes most of the cytoplasm to the newly-formed zygote, it is clear that, if this played an important part in heredity, she would be more important than the father in determining the characters of the offspring. This is not in general the case, but a few characters are known in plants which are inherited only from the mother, like the family name in a matriarchal society. Thus in Mirabilis Jalapa and other plants, the seed borne by the white parts of variegated individuals gives rise to nothing but white, no matter what plant supplies the pollen. In other variegated plants, such as Pelargonium and Oenothere, the pollen exerts a certain influence, but generally less than that of the egg-cell. Since variegation is due to the presence in the cells of colourless instead of green plastids (see PLANTS : Cy tology), and the plastids lie outside the nucleus and are rarely transmitted by the pollen, this is quite intelligible.

Again in certain crosses between plant races a factor influencing sex is transmitted through the cytoplasm only (see SEx) . MENDELIAN INHERITANCE Heredity in Bryophyta (q.v.).—In the higher plants and animals the gametes are inconspicuous, and their hereditary make up can only be inferred from the zygotes which they produce. In the Bryophyta (mosses and liverworts) the haploid generation or gametophyte is the familiar plant. It produces gametes which fuse to form a sporophyte with a double set of chromosomes. This produces spores with the haploid number, from each of which a gametophyte may be formed. The common moss Funaria hygrometrica possesses true-breeding broad- and narrow-leaved races. If they are crossed the sporophyte so formed produces equal numbers of broad • and narrow-leaved offspring. If we de note the haploid gametophytes by the letters B and N we may call the hybrid sporophyte BN. The characters segregate at the reduction division, as is shown by the fact that two of the spores in each tetrad formed from a single diploid cell of a BN sporophyte give rise to B gametophytes, two to N. The diploid generation also varies. BB sporophytes have larger capsules than NN, while BN are intermediate.

Inheritance Without Dominance.

Let us apply this point of view to the higher animals and plants, where it is only in the zygote that differences can be observed. If we mate a yellow guinea-pig with a pink-eyed white, the offspring are cream (the offspring of certain albinos will also have black or chocolate pigment, but the yellow areas of the coat or hairs will always be of a creamy colour). Both yellows and whites always breed true. Now the creams, if mated to a white, give equal numbers of creams and whites; if to a yellow, equal numbers of yellows and creams. Clearly the cream parents are responsible for this hetero geneity. Calling the yellows YY and the whites WW and their gametes Y and W respectively, the product of their fusion, YW, is a cream, producing Y and W gametes in equal numbers. Mated with YY it therefore gives YY (yellow) and YW (cream) ; with WW, YIV (cream) and WW (white). When two creams are mated together the Y eggs are equally likely to be fertilized by Y or W spermatozoa, and therefore produce equal numbers of YY and YW zygotes. Similarly the W eggs give equal numbers of YW and WW. Zygotes are therefore produced in the ratio I YY : 2 YW : I WW, or i yellow : 2 creams : I white. Of course these ratios are not generally obtained unless large numbers of ani mals are counted, any more than the numbers of red and black cards in a hand taken at ran dom from a pack are in general equal. It is to be noted that the results of all these matings are the same whichever type of animal is used as father. The ob ject (for it is known to be a material object) in the gamete which determines the colour is called a gene (q.v.) or factor. A zygote possessing two like genes (as the yellow or white guinea-pig) is called a liomozygote (Gr. oµos, same, Ktryav, yoke, pair) ; one possessing two unlike genes (as the cream) is called a hetero zygote (Gr. 'r€pos, other). Two genes which can form a pair of this kind are called allelomorphs (Gr. aXX iXwv, one another, µo pcH, form) .

Dominance.

Usually the course of events is slightly obscured by the phenomenon of dominance. If we mate pure-breeding black and blue rabbits, the young are all black, but if these hybrid blacks are mated to blues they give equal numbers of blacks and blues. If we call the pure-bred blacks 11, the blues ii (1 symbolizes a gene intensifying blue to black, i its absence) the hybrid blacks are li, giving ecival numbers of 1 and i gametes.Mated with blues (i gametes) they therefore give li (black) and ii (blue) in equal numbers; mated with one another, 3 blacks to one blue ; with homozygous blacks, blacks only. It is usual, fol lowing G. Mendel, to denote the generation produced by crossing two different individuals or races by F,, their offspring when self fertilized or mated inter se by It will be seen that all possible blacks fall into two classes, homozygotes (II) and heterozygotes (li), which can be distinguished by mating them with a blue. When a gene is as effective in one dose as in two, it is said to be dominant ; its allelomorph is said to be recessive. Sometimes these two terms are applied to the characters produced by the genes. Thus black is said to be dominant over blue. In the case of chemical characters such as coat and flower colour, dominance is usually complete. Where form or size is affected the heterozygote is often more or less intermediate, though usually nearer to one parent. But here too dominance may be complete.

A

class of organisms whose members cannot be distinguished from one another by observation is called a phenotype (Gr. 4aivoµac, I appear, Tinos, type) ; a class which can be distin guished from another by breeding tests is called a genotype (Gr. •yivos, race). Thus in the above example, all the black rabbits form one phenotype, but include two genotypes, II and li.Mendelian inheritance (see also MENDELISM) has so far been observed in men, other mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, insects, crustaceans, molluscs, algae, mosses, ferns, monocotyledons and dicotyledons. It is thus probably characteristic of all sexually reproducing organisms. For example, in the pea tallness is dominant over dwarfness, coloured flowers over white flowers, and so on. A recessive character breeds true, a dominant does not necessarily do so. This is important in breeding.

Inheritance of Several Genes.

When two different pairs of allelomorphs are involved in a cross, inheritance is usually inde pendent. For example, shortness of hair is dominant over length in rabbits, and is due to a gene which we may call S. If we mate a homozygous short-haired black (IISS) rabbit with a long haired (so-called "Angora") blue, which, being recessive, must be homozygous (iiss), the offspring are doubly heterozygous short haired blacks (IiSs). Half their gametes carry 1 and half i, and the same is true regarding S and s. As the genes 1 and S show no tendency to stay together, the four possible classes of gametes IS, Is, iS and is are formed in equal numbers. So if the IiSs rabbits are mated with double recessive (iiss) the offspring consist of equal numbers of IiSs (short-haired black) Liss (long-haired black) iiSs (short-haired blue) and iiss (long-haired blue) (fig. 2). If IiSs are mated together the ratios obtained in are 3 black to z blue and 3 short to I long, or, combining the two, 9 short black : 3 short blue : 3 long black : i long blue. The genetical be haviour of double heterozygotes is precisely the same whether they are made from the mating IISSXiiss as above, from IlssXiiSS (long-haired black X short-haired blue) or in any other way, e.g., from the mating IissXiiSs, which will give one IiSs in four. Just the same is true where three or more pairs of allelo morphs are concerned. Thus if a rose-combed black feathered fowl with four toes is mated with a normal-combed buff with five toes, the offspring are rose-combed black with five toes, these characters being dominant, and in the offspring all the eight pos sible recombinations will appear. The processes of inheritance and segregation appear relatively simple as soon as attention is focussed as far as possible on the gametes rather than on the zygotes, even though it is only in rare cases such as the Bryophyta that the gametes can be distinguished on inspection.

Sex-linked Inheritance.

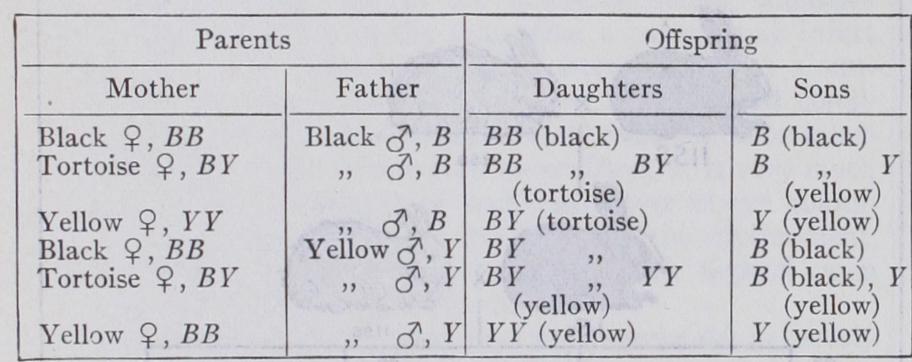

With regard to the genes so far considered the results of reciprocal crosses are exactly the same both in appearance and genetical behaviour. It makes no differ ence whether the gene determining short hair is brought in from the father or the mother, whether that for flower colour is con tributed by the pollen or the ovules, and so on. This is not always the case. An extreme example of the opposite condition is furnished by such Hymenoptera as bees and many wasps, in which fertilized eggs become females, and unfertilized males, which are generally haploid. Thus a dominant gene N in the wasp Habrobracon determines the presence of normal as opposed to defective wings. A normal male is of the composition N, and all his daughters by whatever female are Nn or NN, i.e., normal. (He cannot of course beget sons.) An abnormal male (n) begets all normal daughters with a NN female, half and half with a Nn, and all abnormal with a nn. The sons depend on the composition of their mothers only. NN mothers produce only N males, Nn produce N and n, while nn produce n only. The same principle holds for the bee.Now in an animal where the female is the homogametic sex, of composition XX (see SEx) it is clear that she transmits an X chromosome to all her children; whilst the XY or Xo male trans mits it only to his daughters. Thus if any genes follow this chromosome in their distribution to the gametes, characters de termined by them should be inherited like those of the Hymen optera. This is the case with a number of characters. For ex ample a black male cat may be represented as B, a yellow as Y, a black female as BB, a yellow as YY, whilst the heterozygous female BY is a black and yellow or tortoiseshell cat. Tortoise shell males are rare and generally sterile. (The tabby pattern, or piebaldness, may be superimposed on the above colours, but this does not affect the inheritance.) We have 6 possible matings :— These expectations are fulfilled. The difference between the reciprocal crosses of black and yellow is striking. The same holds when dominance is complete, as in human colourblindness, which is completely recessive.

Similarly where the male is homogametic, as in birds, reciprocal crosses give different results. Thus in the fowl, the Light Sussex breed carry a dominant gene S inhibiting yellow pigment, which is absent in the Rhode Island Red. If we cross a Light Sussex cock (SS) with a Rhode Island hen (s) all the chickens are pro duced from S spermatozoa and are therefore nearly white. The cockerels are Ss, and if crossed with red hens give equal numbers of white and red chickens of both sexes; the pullets (S) behave genetically like Light Sussex hens. If however a Rhode Island cock (ss) is crossed with a Light Sussex hen (S) the pullets, which have not received an X chromosome with an S factor from their mother, are s, i.e., red, the cockerels, Ss, i.e., white (fig. 3). The sexes can thus be distinguished at hatching, a fact of economic importance.

Genes inherited in this way are said to be sex-linked. Sex linkage has been found in men, cats, fowls, pigeons, fish, flies, moths, grasshoppers and in a few dioecious plants. Except per haps in fish, genes are very rarely found in the Y chromosome. Nevertheless such genes are known in man and in Drosophila.

Multiple Allelomorphism.

While genes are generally only found to be allelomorphic in pairs (e.g., those causing dense and dilute colour, or short and long hair in rabbits) this is not always the case. Thus in the rabbit four genes C, Cch, Ch and c are known, which in the homozygous condition, and in the presence of the other genes found in the wild-coloured grey rabbit, deter mine the following colours :— CC wild colour, CChCch "Chinchilla" (black hairs with white tips), "Himalayan" (white with black nose, ears and feet), cc white. Only one of these genes can get into a gamete, only two into a zygote. They are dominant over one another in the order given. Thus any rabbit containing C is fully coloured, and Cchc are chinchilla (rather lighter than the homozygote), C''c is "Himalayan." Hence if we mate CC (wild colour) and cc (white) the offspring are wild coloured, and mated inter se give only wild coloured and white. No Him alayans or chinchillas can appear unless the genes Cch or Ch have been introduced.

Similarly in Primula sinensis the size of the "eye" in the flower is mainly determined by three allelomorphic genes, Ea, E and e. EaEa, EaE, and Eae give the small "Queen Alexandra" eye, EE and Ee the normal eye, and ee the large "Primrose Queen" eye. So a plant bearing the small eye when self-fertilized may give either normal or large eyes in one quarter of its offspring, but cannot give both. As many as eleven multiple allelomorphs belonging to the same series (determining eye colour in Drosophila melano gaster) have been found.

Linkage.

In some cases two genes which are not allelomor phic do not separate independently. Thus in Primula sinensis a gene G renders the stigma green, whilst in gg plants it is red; SS and Ss plants have a short "thrum" style and long stamens, ss a long pin style and short stamens. On crossing GGSS (green thrum) with ggss (red pin) the offspring are GgSs (green thrum). If now the pollen of such plant is used on a ggss, the f our classes of offspring do not appear in equal numbers, but in the ratios 6o GSgs : 4o Gsgs : 4o gSgs : 6o gsgs There is thus an excess of GS and Gs pollen grains, i.e., genes which have entered the zygote in the same gamete tend to leave it in the same gamete. This phenomenon is called coupling. If the doubly heterozygous plants are made up from the cross green pin (GGss) X red thrum (ggSS) the pollen of the offspring used on a double recessive gives 40 GSgs : 6o Gsgs : 6o gSgs : 4o gsgs This is called repulsion, and the two phenomena together called linkage. The two types of GgSs plant may be denominated GS and . If we fertilize them with gs pollen from a double gs gS recessive (red pin) the numbers obtained are: 67 GSgs : 33 Gsgs : 33 gSgs : 67 gsgs and 33 GSgs : 67 Gsgs : 67 gSgs : 33 gsgs Linkage is thus (in this case) slightly stronger in the formation of ovules than of pollen. In a general way if two genes A and B are linked, then when a double heterozygote is formed from ab gametes AB and ab then the gametic series formed are (1—p) AB : pAb : paB : (r —p)ab eggs or ovules, and (r—q) AB: qAb: qaB: (1—q)ab spermatozoa or pollen grains, where p and q are numbers less than 1, which when expressed as percentages are called cross-over values, for reasons which will appear later. If the double heterozygote is formed from • aB gametes Ab and aB the corresponding gametic series are : pAB : (r--p)Ab : (i—p)aB : pab eggs or ovules qAB : (r —q) Ab : (r —q) aB : qab spermatozoids or pollen grains.Now if a zygote is self-fertilized or mated with a similar aB zygote, the offspring are produced in the following proportions : 2+pq AABB, AaBB, AABb and AaBb (i.e., double dominants) AAbb and Aabb i—pq aaBB and aaBb pq aabbOr classing them simply by their appearance : (2+pq)AB : (i—pq)Ab : (i—pq)aB : pqab This is the zygotic series characteristic of repulsion in F2. An AB zygote producing a gametic series of the coupling type, gives ab [2+(I—p) (I—q)]AB :[I—(i—p) : : (I For example, whereas in the absence of linkage the phenotypes AB, aB, Ab, ab would be in the ratios 9:3 : 3 : I ; with linkage values of .25 the numbers would be 33 :15 :r5 :1 for repulsion in F,, :7 :7 :9 for coupling. With strong linkage, p = q = •0 i Would give 20,001 AB : 9,999 Ab : 9,999 aB : i ab in the case of repulsion, 29,805 AB : 199 Ab : 199 aB : 9805 ab. It is clear that in the case of strong repulsion it is exceedingly difficult to obtain a double recessive, and in that of strong coupling fairly difficult to separate the two genes.

In the fly Drosophila melanogaster, and other insect species, in certain fish, and in the fowl and pigeon, the only organisms so far investigated in this respect, all the sex-linked genes are them selves linked. Thus in the fowl, besides the yellow inhibiting gene S (causing silver as opposed to gold plumage) the gene B causing barring of the feathers with white, as in the Plymouth Rock, is sex-linked. If a hen carrying both these genes is mated with a gold unbarred cock of composition bs, all the pullets, which re bs ceive an X chromosome from the father only, are of course bs (gold unbarred), all the cockerels BS (heterozygous silver barred), bs so linkage is complete. If these cockerels are mated with bs hens, the chickens begotten in their first year of breeding are roughly in the proportions : 3 BS (barred silver) : -- (barred gold) : I bS (unbarred bs bs bsver) : 3bbs (unbarred gold) i.e., p = .25. In the later years the linkage is less. In the female of Drosophila melanogaster more than a hundred sex-linked genes show mutual linkage.