Ginkgoales

GINKGOALES Ginkgo biloba, the maidenhair tree, is the solitary survivor of this ancient stock. As already mentioned it is almost extinct. but a few presumably wild trees have been recorded by travellers in parts of China. It is commonly cultivated in gardens of the far east, and is often also grown in North America and Europe and elsewhere. The trees are dioecious and may reach a height of 3o metres; they are freely branched and of pyramidal shape, with a smooth grey bark. The leaves (fig. 9) have a long slender petiole terminating in a fan-shaped lamina which may be entire or two lobed or subdivided into several narrow segments. The veining is very characteristic and like that of many ferns, e.g., Adiantum; the lowest vein in each half of the lamina follows a course parallel to the edge, and gives off numer ous branches, which usually fork as they spread in a palmate man ner towards the leaf margin. The foliage leaves occur either scat tered on long shoots of unlimited growth or crowded at the apex of short shoots (spurs), some of which may subsequently elongate into long shoots.

The "cones," which are very unlike those of cycads and much reduced in comparison, are borne, usually several together, on spur shoots, in the axils of scale leaves. The "male" cone con sists of a stalked central axis bearing a number of loosely dis posed sporophylls. Each of these is formed of a slender stalk terminating in a small knob, from the inner side of which two (rarely three or four) ovoid sporangia hang obliquely (fig. To).

Each sporangium opens by a longitudinal slit, as in cycads (fig.

i o) . The first cell cut off by the microspore is a small and ephemeral prothallial cell. Subsequently all the same cells are produced as in cycads (fig. I z ), and in the same order, but besides the extra prothallial cell there are some minor differences in the later development, e.g., the pollen tube is freely branched, the tube nucleus eventually passes •back into the grain, which it does not do in cycads, and the two sperms are somewhat smaller than those of cycads, though their shape and structure are precisely the same.

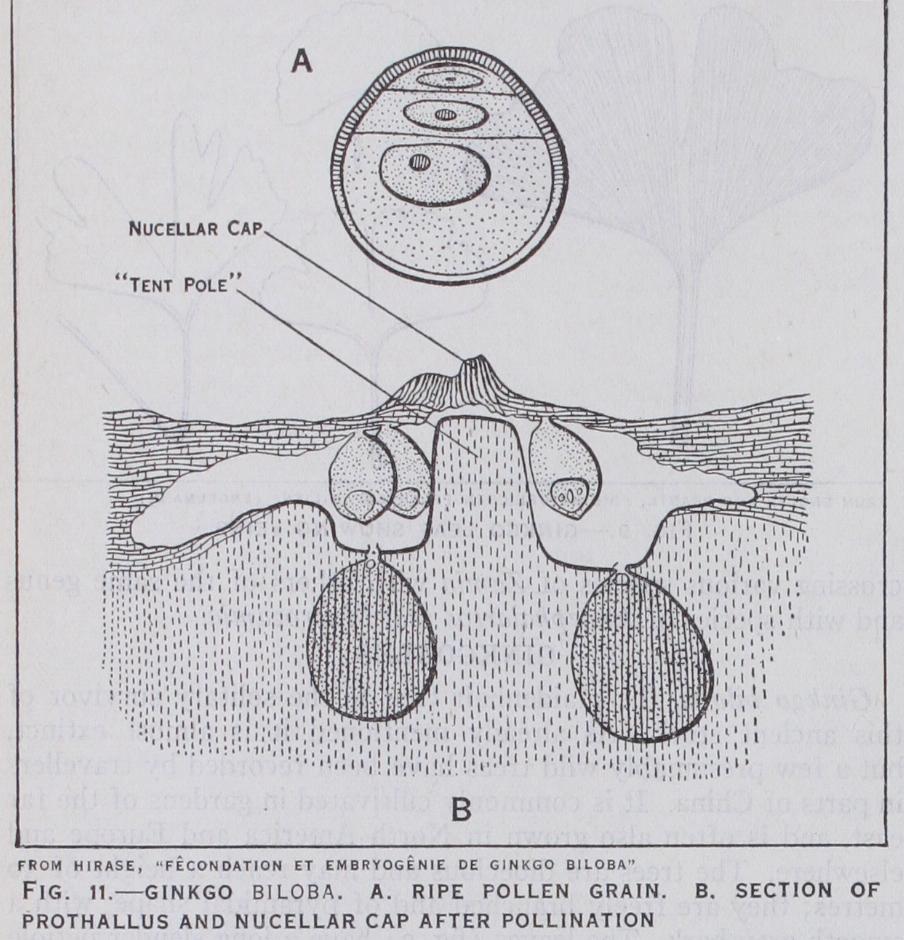

The "female cone" has the form of a long naked peduncle, bear ing a single ovule on either side of the apex (fig. so), the base of each being enclosed by a small saucer-shaped structure, the collar, which probably represents a sporophyll. The young ovule is very similar to that of cycads, a large pollen chamber occupying the apex of the nucellus. The early development of the prothallus takes place as in cycads, but eventually a short thick vertical col umn grows up from the centre and supports the remains of the nucellar cap, which develops much in the same manner as in cycads (fig. i i ). There are usually only two archegonia. The sperms were first observed in 1898 by a Japanese botanist, S. Hirase. The proembryo is similar to that of cycads, and the gen eral organization of the embryo and its relation to the seed are al most identical except that no suspensor is formed. The ripe seed is brownish yellow in colour, about the size of a small plum, and with the same layers in the testa as in cycads. The middle woody layer has usually two (sometimes three) longitudinal ridges. The seed falls soon after (rarely before) fertilization and before the embryo is fully developed.

The anatomical structure of Ginkgo is very similar to that of conifers, and the presence of a few large and much elongated secretory sacs in the pith of the stem is a specific character, while the two leaf traces passing direct into the petiole are also char acteristic.

In its more obvious characters Ginkgo agrees with the coni fers, and before the discovery of the motile sperms it was generally regarded as one. But in most of its more recondite characters it shows a very marked similarity to the cycads and may perhaps be more nearly related to them than to any other division of the Gymnosperms. In any case it is clearly intermediate in the sum of its characters between the cycads and the conifers, as well as showing distinct evidence of relationship with the fossil division Cordaitales, and is one of the links in the chain of evidence which goes to support the view that all the Gymnosperms had a common origin and a Filicinean ancestry.