Gnetales

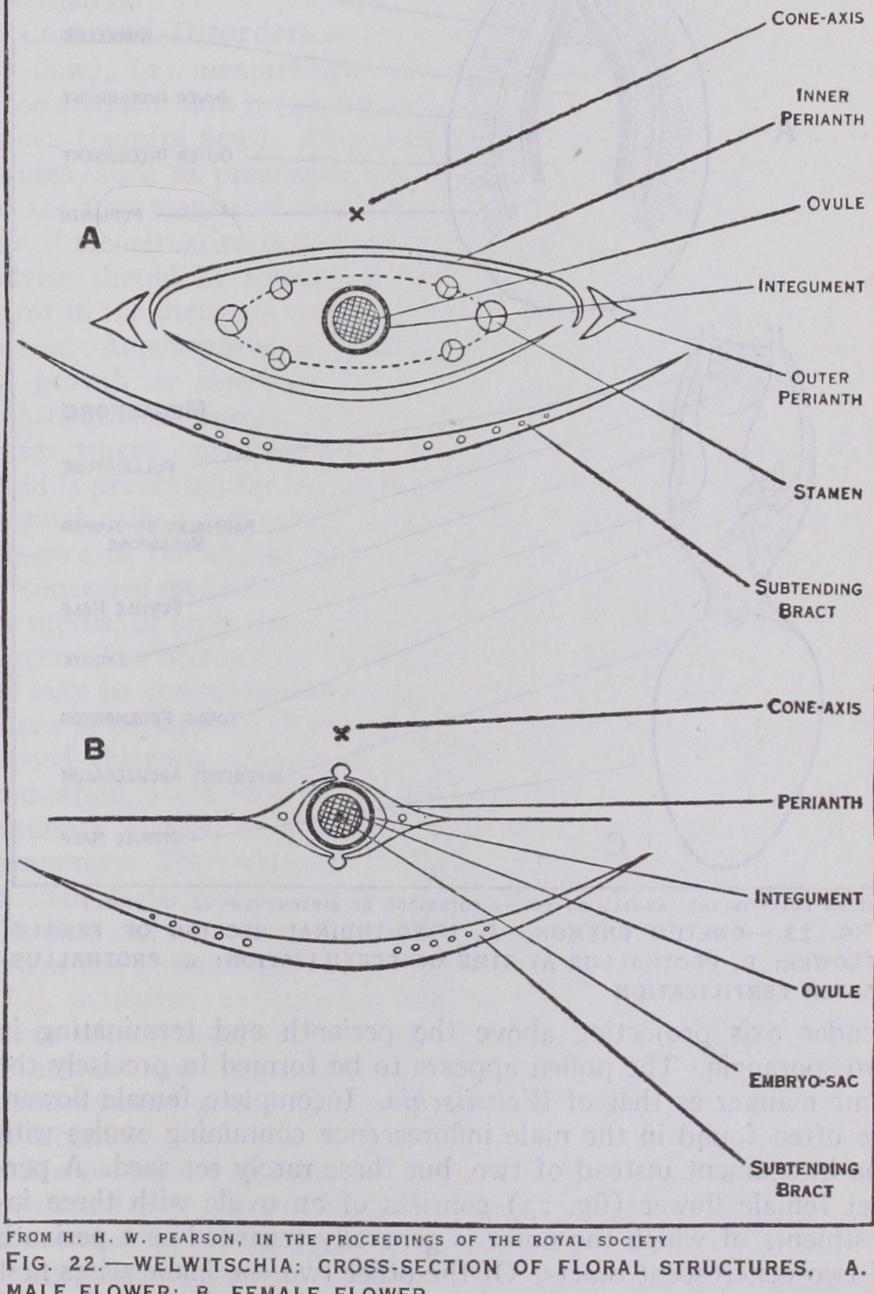

GNETALES These are perennial, normally dioecious plants with opposite simple leaves. The perianth of one or two whorls is distinctive, and sharply contrasts this division with other Gymnosperms. The cones are more complex than in other forms, consisting of an axis bearing decussate pairs of bracts or a number of superposed whorls of bracts, each whorl connate in a cup-like form. In either case the ovulate or staminate structures, which for convenience we may call "flowers," are axillary to these bracts. The flower always consists of one or two pairs of free or connate scales, the perianth, enclosing either a single ovule with a long projecting micropylar tube, or from one to six stamens. It is evident that it is the flowers of Gnetales, especially the female flowers, which are equivalent to the cones of conifers (e.g., compare the female cone of Torreya) and not the whole "cone," which might well be called a compound cone, and which is also comparable to the cat kin-like inflorescence of certain flowering plants.

In their anatomy also the Gnetales show a marked resemblance to angiosperms, as, though the phloem remains typical of gymno sperms in general, true vessels, like those of the flowering plants, are associated with typical gymnospermous tracheids in the wood, and there are no resin canals.

The division includes only three genera, which are so entirely unlike in appearance as to suggest at first sight that each must be regarded as the type of a separate family. But detailed study of development and anatomy has indicated a very close similarity in the former respect between two of the genera, and at least a partial explanation of their complete dissimilarity in appearance, while emphasizing the divergence of the third. They are therefore considered here as forming two families, as follows:— I. EPHEDRACEAE. Much branched small-leaved xerophytic shrubs. Ovule with two integuments containing a prothallus with archegonia, similar to that of conifers. Ephedra.

II. GNETACEAE. Vegetative region of the plant unbranched or sparingly branched. Ovule with one or two integuments and containing a prothallus which does not form archegonia. Leaves large.

A. Tribe Welwitschioideae. Plant tuberous and chiefly underground, developing only two enormously long and straggling, parallel-veined leaves after the cotyledons. tihel witschia.

B. Tribe Gnetoideae. Plant a tree or large woody climber, with numerous net-veined leaves indistinguishable from those of ordinary dicotyledons. Gnetum.

It seems evident that Ephedra, both in general habit and in the possession of archegonia is intermediate in character between the conifers (having points of resemblance to both Cupressaceae and Taxaceae), and the Gnetaceae, while Gnetum has many points of similarity to the true flowering plants. Most botanists have hesi tated (no doubt rightly) to look upon the Gnetaceae as the direct ancestors of the flowering plants, but it is not altogether unlikely that both may have originated from the same stock, which was perhaps not very different from Gnetum. It is indeed a very surprising fact that the geological history of the Gnetales is unknown.

Ephedra

is the largest genus of Gnetales, with about 35 species, and the only one represented in Europe. It is confined to more or less arid warm-temperate and tropical regions and one species is common on sand dunes along parts of the Mediterranean coast. The finer branches are green; the surface of the long internodes is marked by fine longitudinal ribs ; and at the nodes are borne pairs of small, partially connate scale leaves, the general appear ance being similar to that of a stem of Equisetunt or a twig of Casuarina. Some of the branches bear pairs of small cones in the axils of the scale leaves. The cone scales are broad and im bricate. Each male flower (fig. 21) consists of an inconspicuous perianth, composed of two more or less concrescent bracts, en closing an axis projecting beyond the perianth and terminating in two (sometimes more, up to six or eight) sporangia. The resem blance of this structure to a stamen is obvious, but it is no less clearly homologous with the microsporophyll of conifers.The female flower is enveloped in a closely fitting perianth of two more or less connate bracts, as in the male flower. This perianth encloses a single ovule with two integuments, the inner, which is not more than two cells thick, prolonged upwards as a beak-like micropyle, the outer, which is thicker and later becomes woody, only reaching about half way up the micropylar beak. The micropyle secretes a pollination drop, as in conifers.

A prothallus is organized exactly as in conifers, the two to five archegonia being developed from separate superficial cells at the apex, and having long, multicellular, necks. About the time when they first ap pear the tip of the nucellus begins to break down, this disorganization proceeding downwards until there is (when the archegonia are mature) a broad circular pollen chamber open to the top of the prothallus, thus permitting the pollen grains to rest on the necks of the archegonia. The development of the pol len grain is closely similar to that of Larix and it is shed in the 5 nucleate condition. Division of the body cell occurs immediately after pollination and the pollen tube forces its way between the neck cells and discharges its contents into the egg within a few hours. The fusion nucleus divides three times to form eight nuclei, some of which then become organized into walled cells, very loosely connected into a proembryo. Each of these cells, after division of its nucleus, elongates and cuts off a small embryonal cell containing one of the two nuclei, the larger cell remaining, the suspensor, elongating rapidly to thrust the embryo cell deep into the prothallus tissue. The embryo cell divides to form an ovoid mass of cells of which those next to the suspensor elongate in succession giving rise to embryonal tubes which add to the length of the suspensor. The whole process is strongly reminis cent of what takes place in Actinostrobus among the conifers. This description applies more particularly to Ephedra trifurca, and it is uncertain how far the embryo development of other species agrees with it. In any case only one embryo matures.

Welwitschia.—W. mirabilis is the only species of this remark able genus and is found in two isolated and restricted areas of the coastal desert region of Damaraland in South-west Africa. It is by far the most remarkable member of the Gnetales not only in its habit but also both in the form of its flowers and the details of its development. Knowledge of these details is largely due to investigations carried out by H. H. W. Pearson. An adult plant has somewhat the form of a gigantic radish two to four feet in diameter, projecting less than a foot above the ground, and terminating in a long tap-root below. The two strap-shaped leaves trail along the ground to a length of i oft. or more, and become split into a number of narrow thong-like strips. They re tain the power of growth at the base throughout the life of the plant which probably exceeds i oo years. The characteristics of the plant accord well with the interesting suggestion that it may represent an "adult seedling." Numerous circular pits occur on the concentric ridges of the depressed and wrinkled crown, mark ing the positions of former inflorescences, new ridges subsequently appearing outside the old ones. The inflorescences have the form of dichasially branched stalks bearing the cones, from one to 20 in the female plant and up to 5o in the male. The female cone is about an inch long and scarlet in colour, the male smaller and more slender. Each consists of an axis bearing a large number of alternating pairs of overlapping bracts, in the axils of which are the flowers. The staminate flower (fig. 22) is enclosed by a perianth of two opposite pairs of bracts, surrounding a ring of six stamens united below but free above and each terminating in a trilocular anther. In the centre of the flower is an abortive ovule the integument of which projects upwards as a spirally twisted tube with a expansion at its apex. In the development of the pollen grain, a single prothallial nucleus is cut off, which disappears again about the time of pollination. There are only two further divisions resulting in a tube nucleus and two male nuclei, the formation of a stalk cell which occurs without exception in all conifers, as well as in Ephedra, being omitted. There is evidence that pollination is effected by insect agency. The ovulate flower consists of an erect ovule with two investments of which the outer is winged and represents the perianth, formed of a pair of completely connate bracts, the inner being the integument which has the usual long tubular micropyle (fig. 22). No pollen chamber is formed, but numerous pollen tubes grow downwards in the nucellar cap. The megaspore begins to develop as usual, becoming filled with protoplasm containing over i,000 nuclei before walls appear. The latter divide the whole sac into multinucleate compartments, those in the micropylar end containing fewer and larger nuclei, any of which may function as eggs. The remainder contain about a dozen nuclei each, all of which fuse together in the compartment, thus forming a tissue of uninucleate cells which then grows considerably and may be termed the endosperm. The micropylar multinucleate cells put out long tubes which grow upwards into the nucellar cap, and into which the egg nuclei pass. These ascending prothallial tubes meet, and fuse with the descending pollen tubes and at the point of fusion, fertilization occurs. The fertilized egg forms a wall and elongates into a tube from which an embryo tip cell is cut off, the remainder of the tube being the suspensor which carries the em bryo deep into the endosperm. The further development is similar to that in Ephedra, including the formation of embryonal tubes from the young embryo.

Gnetum

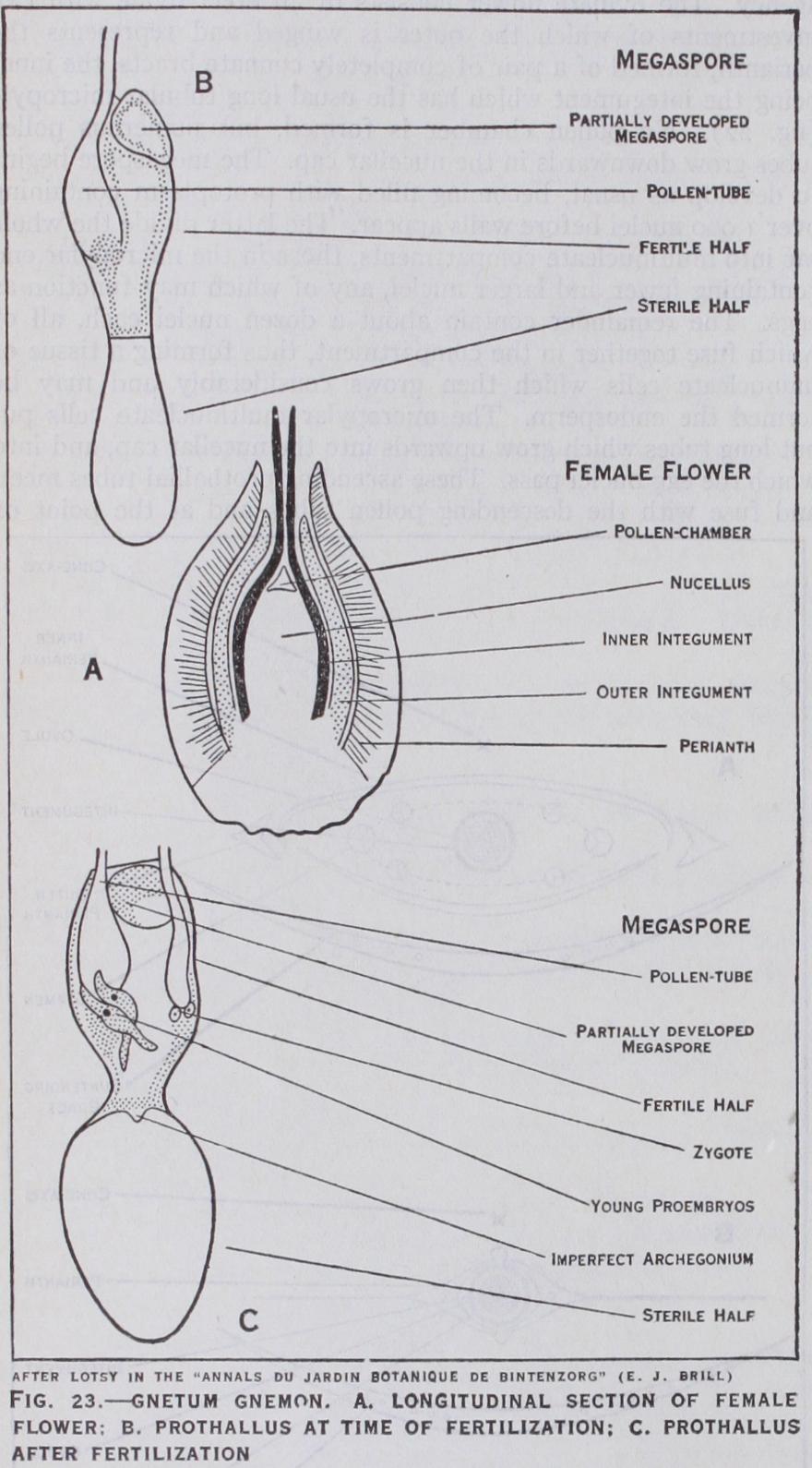

is represented by about 3o species, mostly climbers, found both in tropical America and in tropical regions of the Old World. The oval leaves are two or three inches long and are borne in pairs at the swollen nodes. The cones are long and cylindrical and bear whorls of flowers at each node, accompanied by numer ous sterile hairs, in the axils of cup-like concrescent bracts. In a male inflorescence very numerous flowers may be found, up to about 3,00o in one species, while in a female spike the number of flowers probably does not reach ioo. The staminate flower consists of a perianth of two concrescent bracts enclosing a slender axis projecting above the perianth and terminating in two sporangia. The pollen appears to be formed in precisely the same manner as that of W elwitschia. Incomplete female flowers are often found in the male inflorescence containing ovules with one integument instead of two, but these rarely set seed. A per fect female flower (fig. 23) consists of an ovule with three in vestments of which the outer is generally regarded as a perianth of two concrescent bracts. Of the other two the inner arises first and develops the long slender micropylar tube characteristic of all Gnetales and is followed by a much shorter outer covering, the outer integument. Several megaspores may begin to develop in a young ovule, but only one attains full size. In all species the embryo-sac, as in Welwitschia, becomes filled with numerous free nuclei, and in some species, probably in the large majority, fertilization occurs at this stage, the contents of pollen tubes being discharged into the embryo-sac, any of the nuclei near the micropylar end apparently functioning as eggs. The lower half of the sac then becomes partitioned (as in Welwitschia) into multi nucleate "cells," the nuclei of each cell subsequently fusing so that an endosperm of uninucleate cells results, into which the developing embryos penetrate. Each zygote of G. Gnemon is stated to elongate and form a long tortuous multinucleate suspensor, from the lower end of which a small, also multinucleate, embryo cell is cut off. Walls are said to appear in this "cell" and so reduce it to a tissue of uninucleate cells. This account certainly does not apply to all species and requires confirmation.

In one or two species the lower half of the sac forms a firm endosperm tissue before fertilization, as first observed by J. P. Lotsy in 1899. The accuracy of this observation was questioned by J. M. Coulter in 1908, but it is probable that his preparations did not include the critical stages necessary for confirming or refuting Lotsy's statements, as the latter have since been shown by H. H. W. Pearson to be correct. Coulter described a remarkable devel opment of nutritive tissue, which he named pavement tissue, below the embryo-sac (which is also seen in one or two conifers), and concluded that this had been mistaken by Lotsy for tissue inside the embryo-sac.

The later development of the embryo is similar to that of Welwitschia, and in both genera a rod-like outgrowth is formed from the hypocotyl at its junction with the radicle, which serves as a feeder and draws nourishment from the endosperm during the germination of the seed.

The climbing species of Gnetum are characterized by the production of several concentric cylinders of wood and bast from as many successively formed cambium cylinders produced in the pericycle, as in Cycas.

the books listed below under the chief groups the reader will find the titles of hundreds of detailed papers on the Gymnosperms. None of these are quoted separately with the excep tion of a very few of special importance or historic interest or with an exceptionally full bibliography. General: E. Strasburger, Die Conif eren and Gnetaceen (Jena, 1872) ; Die Angiospermen and die Gymno spermen (Jena, 1879) ; A. B. Rendle, The Classification of flowering plants, vol. i. (Cambridge, 1904) ; J. P. Lotsy, Vortrdge caber Bota nische Stammesgeschichte, band 2 and 3 (Jena, 1909 and 191 i) ; J. M. Coulter and C. J. Chamberlain, Morphology of Gymnosperms (New York, 1925, but only reprinting the 1917 edition with bibliography to that date) ; P. Pilger, "Die Gymnospermen," in Engler's Pflanzfamilien (1926). Cycadales: S. Ikeno, "Das Spermatozoid von Cycas revo luta," Botanical Magazine, Tokyo, vol. x. (1896) ; H. J. Webber, "Spermatogenesis and Fecundation of Zamia," U.S. Department of Agriculture Bulletin 2 (Washington, 1901) ; C. J. Chamberlain, The Living Cycads (University of Chicago Press, 1919) ; and a number of papers in the Botanical Gazette and elsewhere, where a bibliography can be found. Ginkgoales: S. Hirase, " ttudes sur la fecondation, etc., de Ginkgo biloba," Journal of the College of Science, Imperial Univer sity of Japan, Tokyo, vol. xii. (1893) ; A. C. Seward and J. Gowan, "The Maidenhair Tree." Ann. Bot. (19oo) ; H. L. Lyon, "The Em bryogeny of Ginkgo," Minnesota Botanical Studies, vol. iii. (Igo4). Coniferales: W. Dallimore and Bruce Jackson, A Handbook of Conif erae, including Ginkgoaceae (London, 1923) ; A. C. Seward and S. O. Ford, "The Araucarieae, recent and extinct," Phil. Trans. R. Soc., (1906), with full bibliography ; W. T. Saxton, "The Classification of Conifers," New Phytologist, vol. xii. (1913), with bibliography ; A. A. Lawson, "The life history of Pherosphaera," and "The life history of Microcachrys," both in Proc. Linn, Soc. of New South Wales (1923). Gnetales: L. Hooker, "Welwitschia mirabilis." Trans. Linn. Soc. (London, 1864) ; F. O. Bower, "Germination, etc. of Welwitschia," Quart. Journ. of Micr. Sci. (1881) ; "Germination and Embryology of Gnetum." ibid.: (i 882) ; J. P. Lotsy, "Contributions to the life history of Gnetum." Annales du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, vol. xvi. (1899) ; W. J. G. Land, "Ephedra trifurca," Botanical Gazette (1904 and 1907) ; H. H. W. Pearson, "Some Observations on Welwitschia." and "Further observations on Welwitschia." Phil. Trans. R. Soc. (1906 and . (W. T. SA.)