Habsburg or Hapsburg

HABSBURG or HAPSBURG, the name of the family from which sprang the dukes and archdukes of Austria after 1282, kings of Hungary and Bohemia after 1526, and emperors of Austria after 1804. They were Roman emperors from 1438-1806, kings of Spain 1516-170o, and held innumerable other dignities.

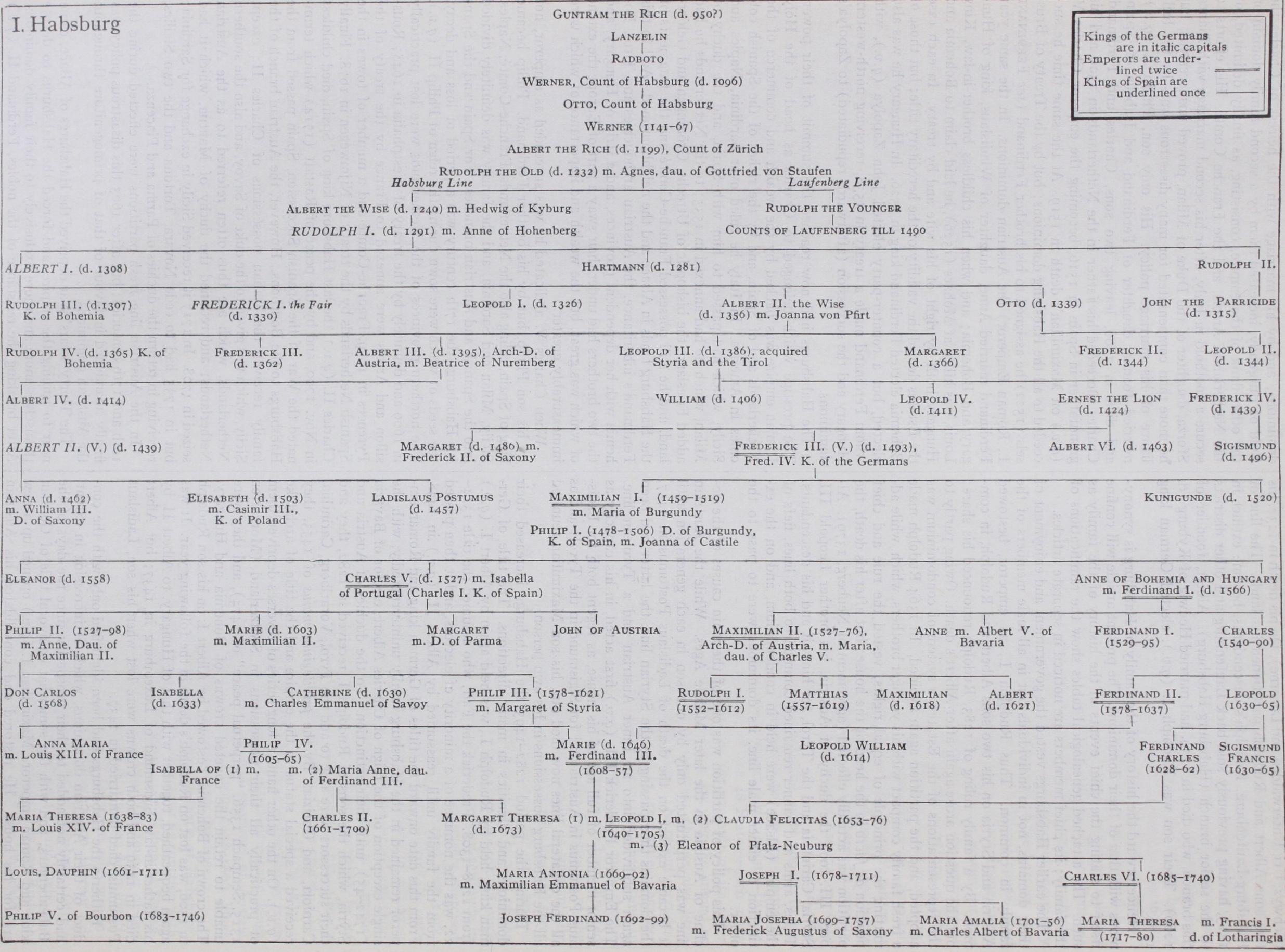

The name Habsburg was derived from the castle of Habsburg, or Habichtsburg (hawk's castle) on the Aar, near its junction with the Rhine, which was built in 1028 by Werner, bishop of Strass burg, and his brother-in-law, Count Radboto. The founder of the house was probably one Guntram the Rich, who has been identi fied with much probability with a Count Guntram who was in volved in a rebellion under Otto I. Radboto's son Werner (d. 1096) and grandson Otto were called counts of Habsburg. Otto's nephew Werner (d. 1167) was father of Albert (d. 1199), who was count of Zurich and landgrave of Upper Alsace. His son Rudolph acquired Laufenburg and the protectorate over the "Waldstatte" (Schwyz, Uri, Unterwalden and Lucerne) . On his death in 1 23 2, his two sons Albert and Rudolph partitioned his lands. The line of Habsburg-Laufenburg, Rudolph's descendants, became extinct in 1415, having previously sold back Laufenburg and other districts to the senior branch (Habsburg-Habsburg). Albert, founder of this branch, who died in 1239, had married Hedwig of Kyburg (d. 1260). Their son was Rudolph I. (q.v.), elected German king 1273.

Henceforward the history of the family of Habsburg is synony mous with that of their dominions. The present article will confine itself to stating the chief events in the history of the family as such. The attached genealogical tables show the ramifications of the family; its chief members are noticed in separate articles.

The earlier Habsburgs vested the government and enjoyment of their domains, not in individuals but in all male members of the family in common. Thus Rudolph I., as emperor, bestowed Austria and Styria on his two sons Albert and Rudolph, in com mon. By a family ruling of 1283, Rudolph renounced his share; but the question arose again after Albert's death. Owing partly to the representations of the Estates, a system of condominium was adopted, and the partition again avoided. In 1364 Rudolph made a fresh family compact with his younger brothers, which, while ad mitting the principle of equal rights, vested the rule and chief position de facto in the head of the house ; but after his death, the partition was actually effected (agreement of Neuberg, 1379). Al bert III. took the duchy of Austria, his brother Leopold III. Styria, Carinthia and the Tyrol, for himself and his descendants. Titles, arms and banner remained common to both lines, fiefs of the empire (Alsace) were held in condominium, and on the ex tinction of either male line, its dominions were to pass to the other.

This policy of partition was one of the main causes of the de cline of Austria in the later Middle Ages. While the Austrian line was perpetuated only by one son in each generation until it became extinct on the death of Ladislaus Postumus in the domains then passing to the Styrian line, the latter had been again subdivided into an Inner Austrian and a Tyrolean line. The Emperor Frederick III. (q.v.) first acted, in his capacity as senior member of full age of his house, as regent both for Ladis laus Postumus in Austria and for Sigismund in the Tyrol; and as all the collateral lines now died out, his son Maximilian reunited all the Habsburg possessions in his own person.

During the period 1282-1493 the Habsburgs increased their dominions and dignities in many directions. The title of Ger man king, held by Rudolph I., was held again by Albert I. (q.v.) from 1298-1308. Frederick the Fair, who assumed the title 2 2, was the nominee of a minority of electors, and it then passed from the family until reassumed by Albert II. (q.v.) in 1438. From this date onward the titles of German king and Roman em peror remained in the Habsburg family uninterruptedly, with the single exception of the reign of Charles Albert, elector of Bavaria , until their extinction. To the duchies of Austria and Styria, which the sons of Rudolph I. received in 1282, they and their successors were able to add the Tyrol, Vorarlberg, Carinthia, Carniola, and Gorizia. By the privilegium maius of 1453, they received a special status in the empire and the title of archduke (q.v.) . On the other hand, a long series of reverses deprived them of practically all their possessions in Switzerland (Morgarten 1315, Sempach 1356, "perpetual peace" of 1474), and they were unable to retain the coveted crowns of Bohemia and Hungary. The crown of Bohemia, bestowed by Albert I. on his son Rudolph in 1306, was lost on Rudolph's death in the following year. It was again bequeathed, together with that of Hungary, to Albert II. by his father-in-law Sigismund of Luxemburg in 1437; but Albert died in 1439 and both crowns were lost when his son, Ladislaus Postumus, died unmarried in Hitherto the Habsburgs had been identified only with the con duct of their Austrian dominions, which, if increasing in extent, had certainly not added to their prosperity since the days of the Babenbergers,; and with the somewhat equivocal title of German king and Roman emperor. Maximilian I. (q.v.) opened up a new era for his house. He restored and consolidated his Austrian dominions ; and by his marriage with the heiress of Charles the Bold of Burgundy, increased them by a second family domain on the other flank of the empire, consisting, as finally delimited, of the Netherlands, Artois, and the Franche Comte. His efforts to secure a foothold in Italy, after his second marriage with Bianca Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan, proved unsuccessful; but he more than compensated for many disastrous wars by the bril liance of his marriage policy. His only son, Philip I. (q.v.), married Joanna, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, and died in 1506, leaving two sons, Charles and Ferdinand. Charles succeeded his father in the Netherlands in 1 so6 and his grandfather in Spain in 1516, becoming the emperor Charles V. (q.v.) on Maximilian's death in 1519. At the same time he suc ceeded to all the Habsburg dominions; but by the Treaty of Brus sels (1522) he assigned to his brother Ferdinand (see FERDINAND I., Roman Emperor) the Austrian dominions. In the same year Ferdinand married Anne, daughter of Wladislaus, king of Hun gary and Bohemia ; and when his childless brother-in-law, King Louis, was killed at Mohacs (1526), he laid claim to Bohemia and Hungary both by right of his wife and by treaty. In each case the Estates denied the validity of the hereditary title; but those of Bohemia elected Ferdinand king in 1526. In Hungary he was also elected, but a counter-party elected John Zapolya (q.v.), with whom Ferdinand made a treaty in 1538, receiving north-western Hungary and the succession (afterwards repudiated) to Zapolya's dominions.

The Habsburgs had now reached the summit of their power. The prestige which belonged to i,rles as head of the Holy Roman empire was backed by the wealth and commerce of the Netherlands and of Spain, and by the riches of the Spanish col onies in America. In Italy he ruled over Sardinia, Naples and Sicily, which had passed to him with Spain, and the duchy of Milan, which he had annexed in ; to the Netherlands he had added Friesland, the bishopric of Utrecht, Groningen and Gelder land, and he still possessed Franche-Comte and the fragments of the Habsburg lands in Alsace and the neighbourhood. Add to this Ferdinand's inheritance, the Austrian archduchies and Tirol, Bo hemia with her dependent provinces, and a strip of Hungary, and the two brothers had under their sway a part of Europe the extent of which was great, but the wealth and importance of which were immeasurably greater.

When Charles V. abdicated he was succeeded as emperor, not by his son Philip, but by his brother Ferdinand. Philip became king of Spain, ruling also the Netherlands, Franche-Comte, Naples, Sicily, Milan and Sardinia, and the family was definitely divided into the Spanish and Austrian branches. For Spain and the Span ish Habsburgs the 17th century was a period of loss and decay, the seeds of which were sown during the reign of Philip II. (q.v.). The northern provinces of the Netherlands were lost practically in 1609 and definitely by the treaty of Westphalia in 1648; Rous sillon and Artois were annexed to France by the treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659, Franche-Comte and a number of towns in the Spanish Netherlands by the treaty of Nijmwegen in 1678. Finally Charles II. (q.v.), the last Habsburg king of Spain, died childless in Nov. 1700, and by the peace of Rastatt (1714) which termi nated the War of the Spanish Succession, Spain passed from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons. However, the Austrian branch of the family received the Italian possessions of Charles II., except Sicily, which was given to the duke of Savoy, and also the southern Netherlands, which are thus often referred to as the Austrian Netherlands; and retained the duchy of Mantua, which it had seized in 1 708. In 1717 it received Sicily in exchange for Sardinia; but in 1735 had to cede Novara, Tortona and the two Sicilies, receiving in return the duchies of Parma and Piacenza.

In the Austrian line fresh partitions were effected during the 16th and 17th centuries; but after 1665 this disastrous policy was finally abandoned in favour of that of primogeniture throughout the Austrian dominions.

The Thirty Years' War deprived the Habsburgs of Alsace, came near to ruining the empire, and forced the Habsburgs to devote themselves more and more exclusively to their family dominions. After breaking the resistance of the nobles, Ferdinand II. (q.v.) declared the thrones of Bohemia (1627) and Moravia (1628) hereditary in his dynasty. Half a century later the Turks were driven back out of Hungary. The Diet of Pressburg (1687) recognized the male line of the Habsburgs in primogeniture as hereditary kings of Hungary; the Peace of Karlovitz (1699) gave them de facto possession of most of Hungary, including Transyl vania, which had already accepted their rule. The Banat was added in 1718.

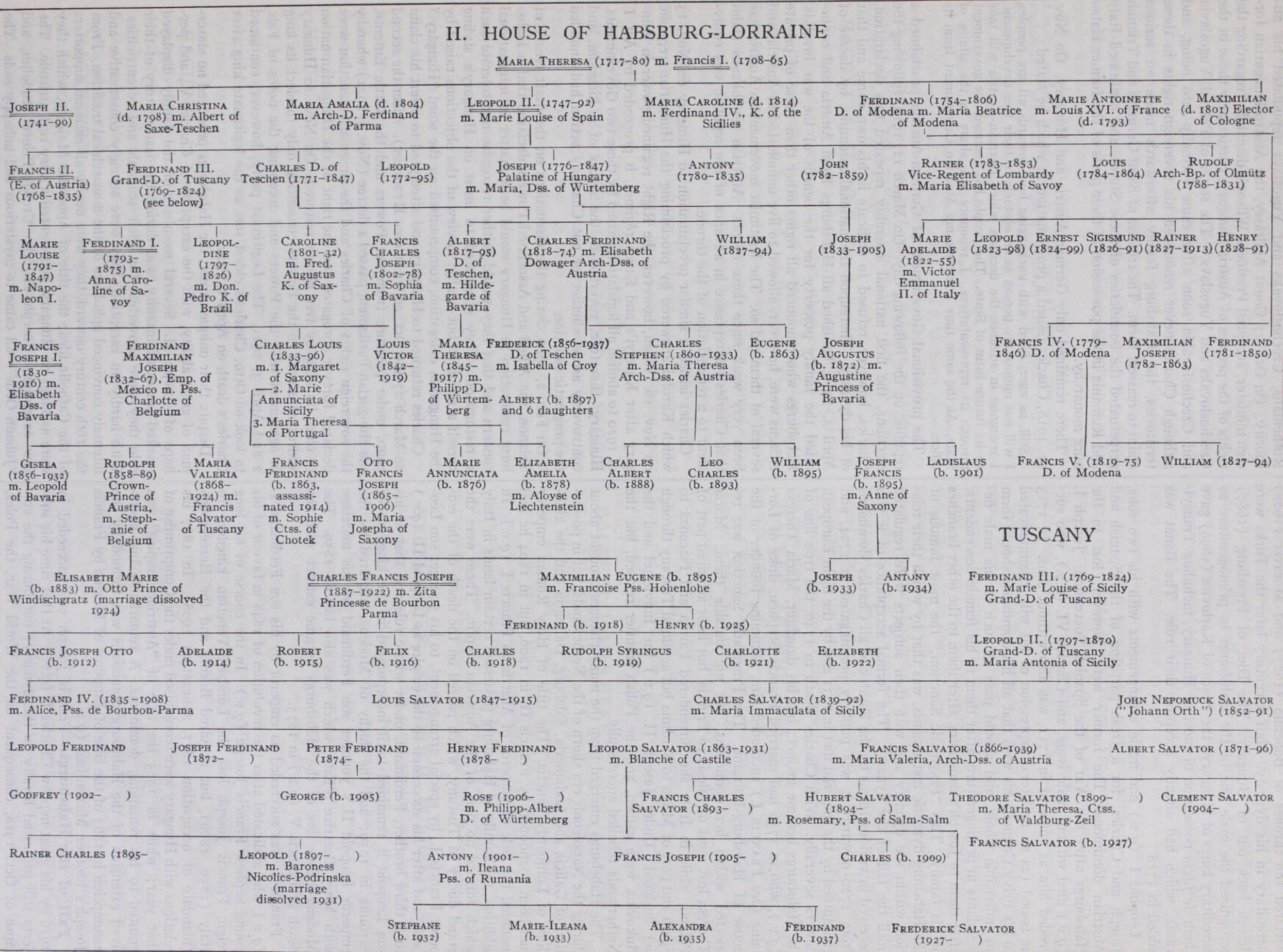

Leopold I. (q.v.) had made arrangements with his two sons, Joseph and Charles, for a fresh partition of the Spanish and Austrian dominions. The former were, however, lost to the Habsburgs after the War of the Spanish Succession. Joseph I. (q.v.) died without male issue, and Charles VI. (q.v.), who suc ceeded him as emperor in 1711, was also without sons. In 1713 he issued (as an unilateral expression of his will, communicated to his Privy Council) his wish that all his dominions should form an indivisible whole, and should pass as such to his male de scendants in primogeniture, after them to his female descendants, after them to Joseph's daughters, after them to the other branches of his family. This "Pragmatic Sanction," the most famous of the Habsburg dynastic instruments, was that by which their rela tion within the dynasty and with their subjects were regulated until the fall of the dynasty. The formal acceptance of it was received in various forms by the Estates of all Charles' dominions from 17 20 onward; it was publicly promulgated in 1724, and guaranteed by the imperial diet in 1731 and by the main European powers severally. With Charles' death in 1740, the true line of the Habsburgs became extinct ; but his daughter, Maria Theresa (q.v.), who in 1736 had married Francis Stephen, duke of Lor raine (see FRANCIS I.) succeeded him, becoming founder of the house of Habsburg-Lorraine. The Pragmatic Sanction was re spected within her dominions, but not outside them. Maria Theresa lost most of Silesia to Prussia, but later acquired part of Poland, while in Italy she surrendered Parma and Piacenza to Spain and part of Milan to Sardinia but acquired Tuscany through her husband. Under Joseph II. (q.v.) the Innviertel and the Bukovina were gained, and the Polish frontier revised, but the Netherlands rebelled successfully.

The Habsburgs emerged from the many changes brought about during the Napoleonic era shorn of the Netherlands, but in posses sion of Galicia and Lodomeria, Salzburg, Dalmatia and the king dom of Lombardy-Venetia. The title of Holy Roman emperor had been abandoned by Francis II. in 1806, but in 1804 he had assumed the title of emperor of Austria as Francis I. (q.v.). In addition, the family of Habsburg possessed certain lands in Italy which formed no part of the Austrian empire. These were the grand duchy of Tuscany, which passed on the death of the em peror Francis I., by special arrangement, to his younger son Leo pold, and after his succession to the empire as Leopold II. (q.v.) to a third brother, Ferdinand, under whose rule and that of his son Leopold it remained until incorporated in the kingdom of Sardinia in 1859; and the duchy of Modena, acquired by the emperor Leopold II.'s younger son Ferdinand by his marriage with Mary Beatrice d'Este, which was also lost in 1859. The Modena-d'Este line of the Habsburgs became extinct with the death of Francis V. (q.v.) in 1875.

Francis I. was succeeded as emperor by his son Ferdinand I. (q.v.), who abdicated after the revolution of 1848 in favour of his young nephew Francis Joseph (q.v.). In the course of his long reign, Francis Joseph lost the Lombard-Venetian kingdom to Italy (1859, 1866), but acquired Bosnia and the Hercegovina (mandate of occupation 1877, annexation 1908). In 1867 his relations with Hungary were reorganised under the Compromise of that year; while in 1915 the title of "Austrian empire" was granted to his remaining dominions. A remarkable but short lived extension of the Habsburg dominions was formed by the assumption in 1863 of the title of Emperor of Mexico by Francis Joseph's brother Maximilian (q.v.).

Fall of the Habsburgs.

Francis Joseph was succeeded in 1916 by his great-nephew Charles I. (q.v.). At that time his sub jects still protested loyalty to the dynasty; but during the col lapse of Oct. 1918, consequent on the World War, the Poles, Ruthenians, Czechoslovaks and Yugoslays repudiated his au thority. On Oct. 27 Count Andrassy, the Austro-Hungarian for eign minister, accepted President Wilson's demands "regarding the rights of the peoples of Austria-Hungary, particularly those of the Czechoslovaks and Yugoslays." The states of Poland, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia soon after came formally into being, and although Charles never renounced his sovereign rights in these territories, the Habsburg family afterwards made no serious claim to reassert them. The treaties of Saint Germain and Trianon perpetuated the boundaries of these States, and confirmed Italy and Rumania in the possession of their parts of the former Habs burg monarchy.There remained only German-Austria and Hungary. On Nov. I 1, 1918, Charles issued a proclamation in which he stated : Still, as ever, filled with unchanging love towards all my peoples, I will not oppose my person as an obstacle to their free development. I recognise in advance the decision which German-Austria will take on its future form of State. The people has assumed the government through its representatives. I renounce any share in the affairs of State. At the same time I remove my Austrian Government from its office.

The provisional Government of German-Austria proclaimed a republic on the following day. On March 12, 1919, following the elections, the first national assembly repeated this declaration. Charles, however, refused to abdicate in his own name and that of his dynasty. Thereupon the national assembly, by decree of April 2, 1919, banished all Habsburgs from Austria and confis cated the family property for the benefit of the war invalids. Habsburgs who renounced all rights other than those of private citizens were, however, allowed to live unmolested in Austria, and several of them did so. The legitimist movement in Austria has been very weak since these events. Austrian republicans claim that Charles's acceptance in advance of the republic was equiv alent to a renunciation of the throne.

Charles issued a similar proclamation to Hungary on Nov. 13 which Karolyi answered by proclaiming the Hungarian republic on Nov. 16. When, however, the Right regained power in Hun gary after Karolyi's and Kun's regimes, it proceeded by Act I. of 1920 to abolish all legislation passed by these two Governments. Hungary, therefore, reverted to the status of a kingdom, and controversy arose whether or not Charles's action had annulled the pragmatic sanction.

On Feb. 2, 192o, during the discussions on the draft treaty of Trianon, the Allied and Associated Powers declared that a Habs burg restoration in Hungary would be a matter of international concern and that they would neither recognise nor tolerate such a restoration. They attempted to insist on Hungary's styling herself a republic, but finally, in view of the objections raised by the Hungarian delegation, compromised on the word "Hungary." Charles returned to Hungary and attempted to assert his claim on March 27 and Oct. 20, 1921 (see HUNGARY). After the second coup, under pressure from the Powers and the Little Entente. the Hungarian Parliament passed a decree (Nov. 3, 1921) whereby the sovereign rights of Charles and the pragmatic sanction were declared forever abrogated and the right of the Hungarian nation to elect its king by free choice restored. On Nov. 1 o Hungary addressed a note to the Powers consenting only to elect its king in agreement with the Powers and accepting the notes of Feb. 2 and April 3, 1921. The Legitimist party, however, continued to look on Otto, Charles's eldest son, as the legitimate king after Charles's death on April 1, 1922.

Despite their unique career, the Habsburgs produced no states man of great ability, with the exception of Charles V., and per haps of Joseph II. Several members of the family displayed marked traces of insanity, and during the last century of their rule they were proverbial for their scandals and eccentricities. With hardly an exception, they were strongly conservative and intensely convinced upholders of the monarchical tradition. From the 16th century onward, they were nearly all extreme supporters of the Catholic idea; the title of Apostolic Majesty, which they wore as kings of Hungary, represented a very real attitude. The few exceptions—Joseph II., the Crown Prince Rudolph, and "Johann Orth"—all came to mysterious and unhappy ends. The family tradition was exceedingly strict among them to the last, as was well exemplified when the Archduke Francis Ferdinand (q.v.) contracted his morganatic marriage. They owed their posi tion chiefly to outward circumstance and to a series of marriages so adroit and successful as to give rise to the proverb "Bella gerant alii, tu, felix Austria, nube" (Let others wage war, do you, happy Austria, marry) . As a family they succeeded in amass ing great wealth, the fortunes accumulated by the Modena and d'Este branch and their heirs being particularly brilliant. After the fall of their dynasty they lost all valuables and estates owned in virtue of their rank. The income of the senior branch of the family was left very small.

For the origin and early history of the Habsburgs see G. de Roo, Annales rerum ab Austriacis Habsburgicae gentis principibus a Rudolpho I. usque ad Carolum V. gestarum (Innsbruck, 1592, fol.) ; M. Herrgott, Genealogia diplomatica augustae gentis Habsburgicae (Vienna, 1737-1738) ; E. M. Furst von Lichnowsky, Geschichte des Hauses Habsburg (Vienna, 1836-1844) ; A. Schulte, Geschichte der Habsburger in den ersten drei Jahrhunderten (Innsbruck, 1887) ; T. von Liebenau, Die Anfange des Hauses Habsburg (Vienna, 1883) ; W. Merz, Die Habsburg (Aarau, 1896) ; W. Gisi, Der Ursprung der Hauser Zahringen and Habsburg (1888) ; and F. Weihrich, Stammtafel zur Geschichte des Hauses Habsburg (Vienna, 1893) . For the history of the Habsburg monarchy see Langl, Die Habsburg and die denk wiirdigen Statten ihrer Umgebung (Vienna, 1895) ; and E. A. Freeman, Historical Geography of Europe (1881). (C. A. M.)