Hastings

HASTINGS, a municipal, county and parliamentary borough and watering-place of Sussex, England, one of the Cinque Ports, 62 m. S.E. by S. from London, on the S.R. Pop. Rock shelters on Castle hill and numerous flint implements which have been discovered at Hastings suggest an extensive early popu lation, and there are earthworks and a promontory camp probably of early Iron Age or Roman-British date. Hastings was not a Roman settlement, but it was a place of some note in the Anglo Saxon period. In 795 land at Hastings (Haestingaceaster, Haes tingas, Haestingaport) was included in a grant, which may pos sibly be a forgery, of a South Saxon chieftain to the abbey 1of St. Denis in France; and a royal mint was established at the town by Aethelstan. The battle of Hastings (q.v.) in 1o66 was fought near the present Battle Abbey, about 6 m. inland. After the Con quest William I. made the earthworks of the existing castle. By 1o86 Hastings was a borough and had given its name to the rape of Sussex in which it lay. The town at that time had a harbour and a market. Whether Hastings was one of the towns afterwards known as the Cinque Ports at the time when they received their first charter from Edward the Confessor is uncertain, but in the reign of William I. it was among them. These combined towns, of which Hastings was the head, had special liberties and separate jurisdiction under a warden. The only charter peculiar to Hastings was granted in 1589 by Elizabeth, and incorporated the borough under the name of "mayor, jurats and commonalty," instead of the former title of "bailiff, jurats and commonalty." Hastings returned two members to parliament probably from 1322, and certainly from 1366, until 1885, when the number was reduced to one.

It is situated at the mouth of two narrow valleys, and, being sheltered by hills on the north and east, has an especially mild climate. A parade fronts the English Channel, and connects the town on the west with St. Leonard's, the residential quarter which is included within the borough. Both Hastings and St. Leonard's have fine piers ; there is a covered parade known as the Marina, and the Alexandra Park of 75 ac. was opened in 1891. There are also numerous public gardens. The sandy beach is extensive, and affords excellent bathing. On the brink of the West Cliff stand a square and a circular tower and fragments of the castle, erected soon after the time of William the Conqueror; together with the ruins, excavated in 1824, of the castle chapel, a transi tional Norman structure 1 1 o ft. long, with a nave, chancel and aisles. Besides the chapel there was formerly a college, both being under the control of a dean and secular canons. The deanery was held by Thomas a Becket, and one of the canonries by Wil liam of Wykeham. Titus Oates, whose father was rector of the parish, was baptized in 1619 in the Church of All Saints. The prosperity of the town depends almost wholly on its reputation as a watering-place, but there is a small fishing industry. The fish market is beneath the castle cliff. The parliamentary borough re turns one member. The county borough was created in 1888.

Battle of Hastings.

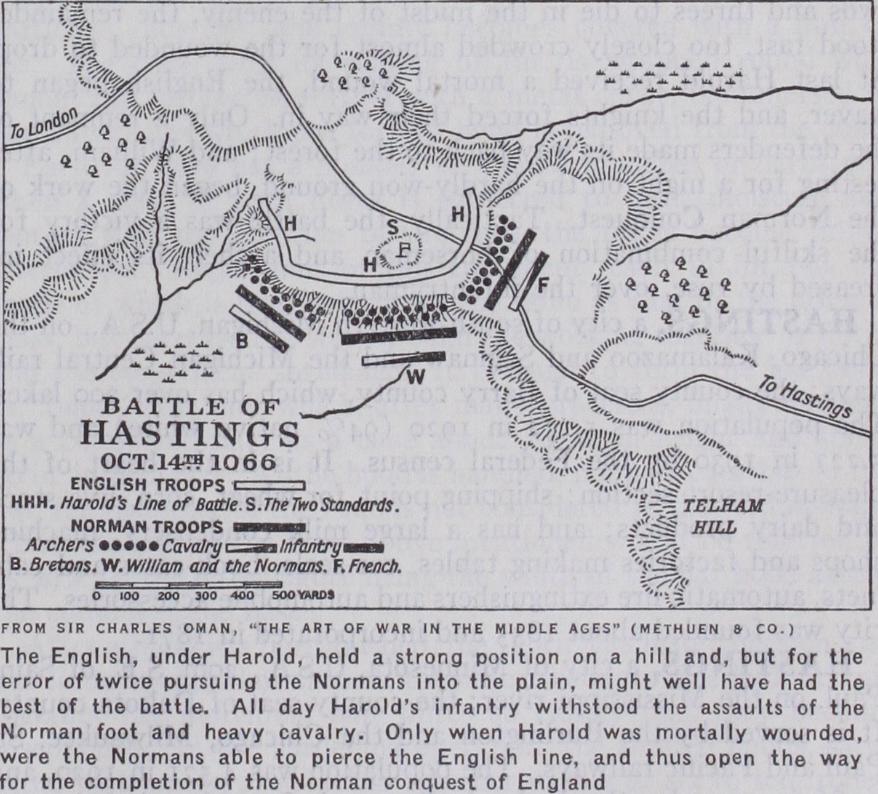

On Sept. 28, 1o66, William of Nor mandy, bent on asserting by arms his right to the English crown, landed at Pevensey. King Harold, who had destroyed the invad ers of northern England at the battle of Stamford Bridge in York shire, on hearing the news hurried southward, gathering what forces he could on the way. He took up his position, athwart the road from Hastings to London, on a hill' some 6m. inland from Hastings, with his back to the great forest of Anderida (the Weald) and in front of him a long glacis-like slope, at the bottom of which began the opposing slope of Telham Hill. The English army was composed almost entirely of infantry. The shire levies, for the most part destitute of body armour and with miscellane 'Freeman called this hill Senlac and introduced the fashion of describing the battle as "the battle of Senlac." J. H. Round, however, proved conclusively that this name, being French (Senlecque), could not have been in use at the time of the Conquest, that the battle field had in fact no name, pointing out that in William of Malmesbury and in Domesday Book the battle is called "of Hastings" (Bellum Hastingense) , while only one writer, Ordericus Vitalis, describes it 200 years after the event as Bellum Senlacium. See Round, Feudal England, p. 333 et seq. (1895) .

ous and even improvised weapons, were arranged on either flank of Harold's guards (huscarles), picked men armed principally with the Danish axe and shield.

Before this position Duke William appeared on the morning of Oct. 14. His host, composed not only of his Norman vassals but of barons, knights and adventurers from all quarters, was ar ranged in a centre and two wings, each corps having its archers and arblasters in the front line, the rest of the infantry in the sec ond, and the heavy armoured cavalry in the third. Neither the arrows nor the charge of the second line of foot-men, who, unlike the English, wore defensive mail, made any impression on the English standing in a serried mass behind their interlocked shields.' Then the heavy cavalry came on, led by the duke and his brother Odo, and encouraged by the example of the minstrel Tail lefer, who rode forward, tossing and catching his sword, into the midst of the English line before he was pulled down and killed. All along the front the cavalry came to close quarters with the defenders, but the long powerful Danish axes were as formid able as the halbert and the bill proved to be in battles of later centuries, and they lopped off the arms of the assailants and cut down their horses. The fire of the attack died out and the left wing (Bretons) fled in rout. But as the fyrd levies broke out of the line and pursued the Bretons down the hill in a wild, formless mob, William's cavalry swung round and destroyed them, and this suggested to the duke to repeat deliberately what the Bretons had done from fear. Another advance, followed by a feigned re treat, drew down a second large body of the English from the crest, and these in turn, once in the open, were ridden over and slaughtered by the men-at-arms. Lastly, these two disasters hav ing weakened the defenders both materially and morally, William subjected the huscarles, who had stood fast when the fyrd broke its ranks, to a constant rain of arrows, varied from time to time by cavalry charges. These magnificent soldiers endured the trial for many hours, from noon till close on nightfall; but at last, when the Norman archers raised their bows so as to pitch the ar rows at a steep angle of descent in the midst of the huscarles, the strain became too great. While some rushed forward alone or in twos and threes to die in the midst of the enemy, the remainder stood fast, too closely crowded almost for the wounded to drop. At last Harold received a mortal wound, the English began to waver, and the knights forced their way in. Only a remnant of the defenders made its way back to the forest; and William, after resting for a night on the hardly-won ground, began the work of the Norman Conquest. Tactically, the battle was a victory for the skilful combination of horseman and archer, its effect in creased by ruse, over the infantryman.