Hawaii

HAWAII (hah-wi'i; native hah-vah'e-e), HAWAIIAN (N. SANDWICH ISLANDS, capital Honolulu (q.v.), geographi cally a chain of islands near the centre of the north Pacific ocean, 1,578 m. from E.S.E. to W.N.W., between 18° 55' and 28° 25' N. and 154° 48' and 178° 25' W. Politically, as a Territory of the United States, it consists of the islands ceded by the Republic of Hawaii to the United States in 1898 and made a Territory by Congress in 1900, and hence excludes the small coral island, Mid way, which was acquired by the United States in 1859 and has been used since 1902 as a cable station, and includes two small un inhabited coral islands not in the chain, Johnston (or Cornwallis) and Palmyra.

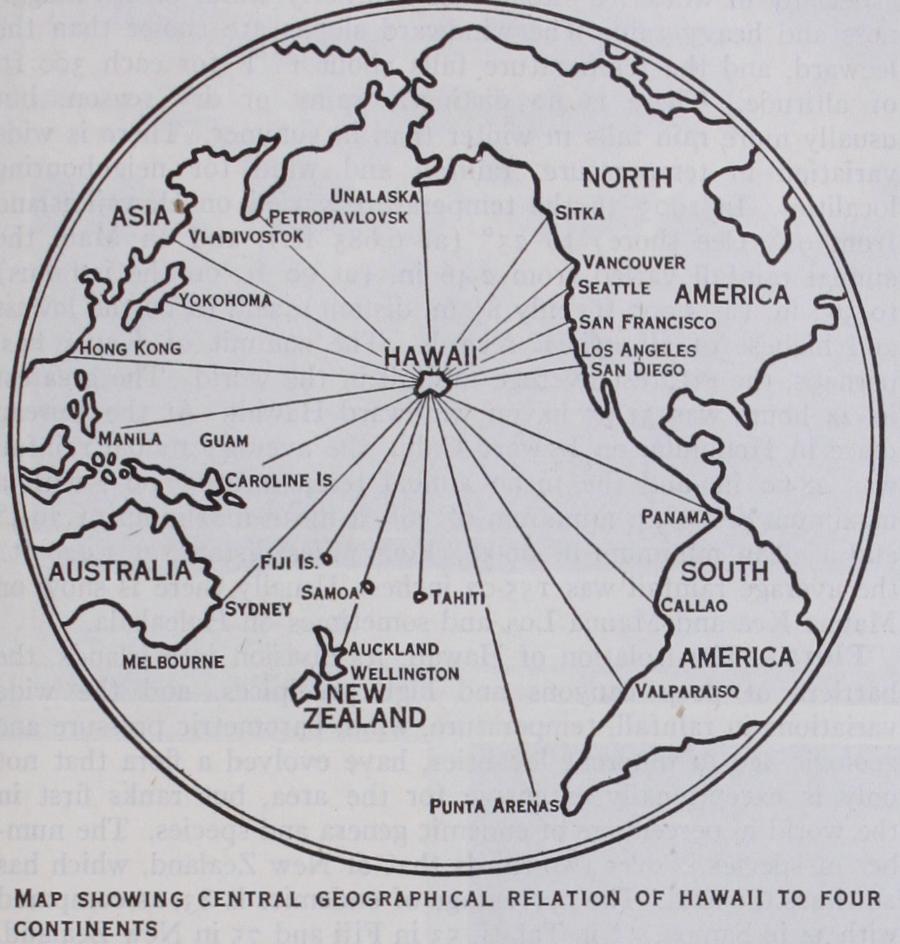

Hawaii, comprising both volcanic and coral islands built up from depths of 15,000 to 18,000 ft., is the northernmost of the central Pacific island groups. It has the largest area (6,412 sq.m.), and greatest altitude (13,825 ft.). It is also the most isolated of important land areas. The nearest important groups to the south are Samoa, 2,263, and Tahiti, 2,390 nautical miles. To the north, Unalaska in the Aleutian islands is 2,106, and to the west, Guam is 3,337 miles. The distances in nautical miles from Honolulu to principal ports of the Pacific are: San Francisco, 2,ioo; Los Angeles, 2,226; Seattle, 2,409; Sitka, 2,395; Yokohama, 3,445; Sydney, 4,424; Panama, 4,665; Manila, 4,778; Hongkong, 4,961; Valparaiso, 5,916. Cape Horn is 6,488 miles. The large, high, inhabited islands, Hawaii (4,03o sq.m.), Maui (728), Molokai (260), Lanai (141), Kahoolawe (45), Oahu (604), Kauai (555) and Niihau (72), together with their nearby small uninhabited islands, form the east-south-east fourth or about 375 m. of • the chain, extending to 2 2 ° 14' N. and i6o° 15' W. The islands of the remainder of the chain are so small that their total area is only 6 sq.m., and yet they afford a rich field for the naturalist. Those in the west half of this part of the chain are coral (mostly sand) islands; those in the other half, forming a transition link with the large inhabited islands, are lava-rock. The islands of the entire chain apparently were formed beginning at the westerly and finishing at the easterly end, where there are still active volcanoes.

Westerly Islands.

The small westerly group are remains of larger islands which have mostly eroded. The lava-rock ones rest on more or less extensive banks lying at small depths, and the coral ones are sand islands or islets on the rims of large atolls. Those of lava-rock are Nihoa or Bird (903 ft. high), Necker (276), French Frigates shoal (a rock 120 ft. high and 16 sand islets) and Gardiner (i 7o) ; the coral ones, Io-4o ft. high, are Laysan, Lisiansky, Pearl and Hermes reef (12 islets), Midway (Sand island, a cable station and Eastern island), and Ocean or Cure (Green island, and two islets). In addition there are Frost shoal, Brooks shoal, Maro reef, Dowsett reef and Gambia bank, which are just awash or do not reach the surface. None are inhab ited except for the cable station at Midway. For a time Laysan was occupied for its guano until the deposits became exhausted. Necker has stone platforms and enclosures, perhaps temples, of unknown origin; stone images and dishes found there are ir. Honolulu museum. The Hawaiians anciently visited Nihoa and Necker to obtain materials for their famous feather work as well as for fish. There is little vegetation except grasses and shrubs. The waters abound in fish and turtles, and, especially at Pearl and Hermes reef, a species of hair seal found nowhere else. These islands are most noted, however, for their bird life, and in 1909 all of them except Midway were created by the National Govern ment into the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation, to protect them from Japanese poachers who, for the feathers, killed some 300,000 birds in one season. Collectively, they form the largest and most numerous bird colony in the world. One naturalist estimated at over ten millions the number of birds, resident and migratory, in a single year at Laysan alone, an island i m. by 1 m., with a lagoon a mile long in the centre. These are of many varieties, some not found elsewhere, including frigate, man-o'-war, tropic, mutton and miller birds, the Laysan canary, finch, duck and honey-eater, terns, curlews, turnstones, stilts, plover, shovelers, boobies, tatlers, petrels and shearwaters that burrow like rabbits, rails that have only rudimentary wings and cannot fly, and, most numerous, albatrosses that indulge much in curious dances, two by two. Many are remarkably unafraid of man.

Hawaii.

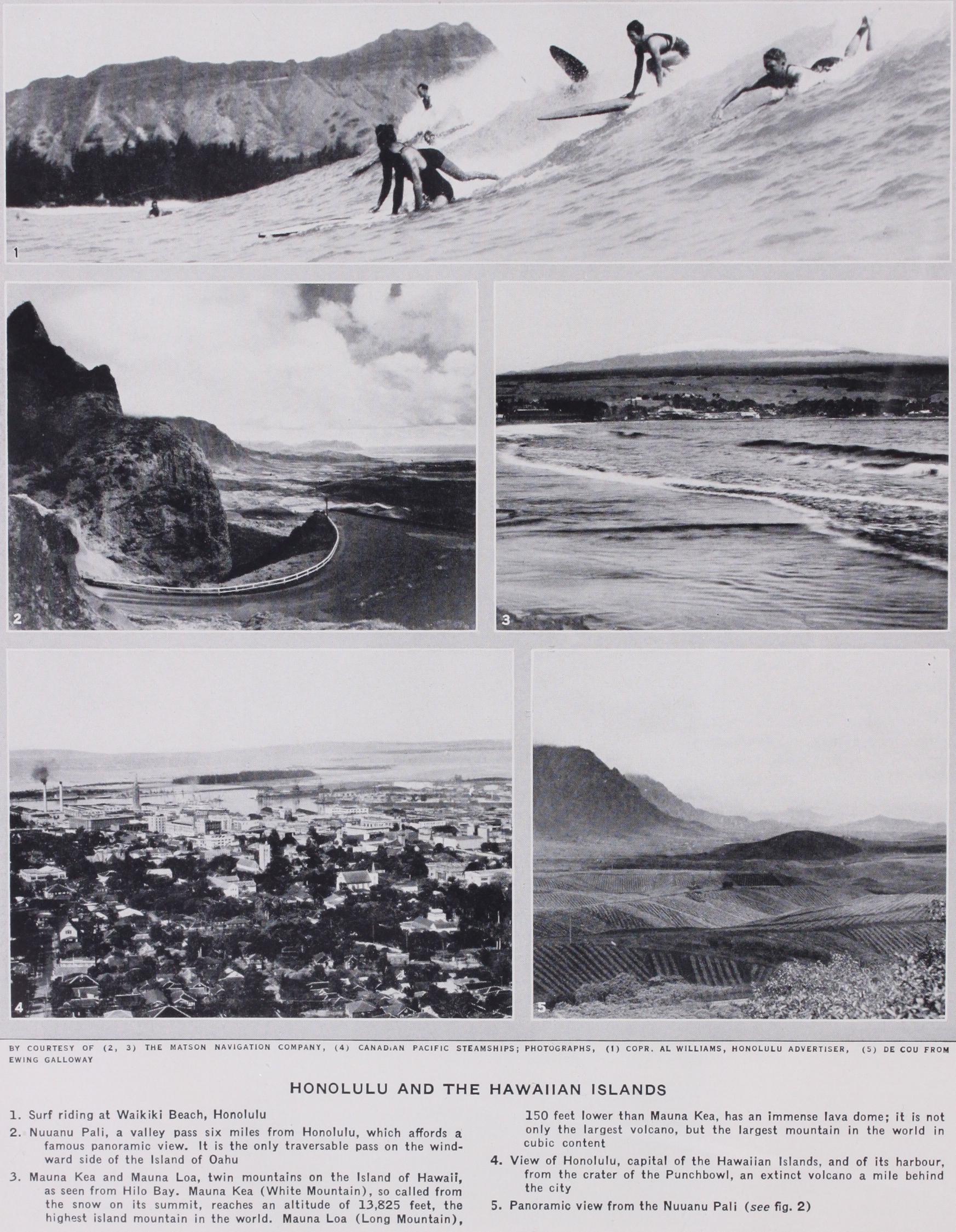

The island of Hawaii, which contains two-thirds of the area of the group, is roughly triangular in shape, with sides of 9o, 75 and 6o m. ; it consists of five volcanic mountains about 20 m. apart, connected by saddles 3,000-7,00o ft. high, formed by overlapping lava flows. Being the newest island, and still in the making by volcanic action, little of its 297 m. of coast is bordered with coral reefs, and there has been little erosion except along the 6o m. of the north-east coast from the principal harbour, Hilo, to the north end of the island, the windward side of the older moun tains, where copious rains and ocean waves and currents have created valleys and cliffs increasing northward in depth and height and culminating in the Waipio and Waimano valleys, several thousand feet deep, receding from coastal cliffs 1, 50o ft. high. Throughout the rest of the island there is not a stream except at times of unusual rain—partly because of the porosity of the rocks and soils, and, on the leeward side, partly because of insufficiency of rain.The Kohala mountain or range (5,505 ft.), the oldest, its wind ward side deeply eroded, its top a water sponge, its leeward side dry, with the higher slopes covered with cinder cones, forms the north angle of the island. Next, south-easterly, is Mauna Kea ("White Mountain," so-called from the snow on its summit) . There are glacial markings on its upper windward slopes. At 13,000 ft. there is a small lake, which often freezes over, and nearby are extensive quarries of fine-grained, compact greyish stone, of which the Hawaiians of old made their best adzes and other implements. The crater has disappeared, blown up in an explosive eruption, or covered by reddish cinder cones, which in great numbers dot the summit and upper slopes. This is not only the highest mountain of the group but the highest island mountain in the world (13,784 feet). In a real sense it is also the highest of all mountains in the world, for, although many others are higher above sea-level, this starts from a great plain 18,00o ft. below sea-level and is built up from that as a single mountain, rising within a distance of 5o m., to a height of nearly 32,00o feet.

South-westerly from Mauna Kea is Hualalai (8,269 ft.), whose summit, like that of Mauna Kea, has no great crater and is cov ered with cinder cones, but, unlike Mauna Kea, has many small pit craters. Its only flow in historic times was in 1801. Further south is Mauna Loa, "Long Mountain," twin of and Ioo ft. lower than Mauna Kea. Except for the cinder cones of the latter it would be higher. It is an immense lava dome, not only the largest volcano, but the largest mountain in the world in cubic content ; it discharges more lava than any other volcano. On the summit is an elongated pit crater, Mokuaweoweo (3.7 sq.m.), with vertical walls soo to 600 ft. high, from which radiate black and brown lava flows of bygone ages. While at times, especially preceding eruptions, the summit crater is exceedingly active, no flow has originated there in historic 'times. All historic flows, ex cept submarine, have burst from the sides at elevations of 7,000 to 13,00o ft., usually on two lines running north-east and south west respectively from the summit. The principal flows of the last century were in (33 m. long, i m. wide in places), 1868, 1877 (submarine), ; 1907-16-19-26, and 1935-36, when the flow was bombed to divert its course.

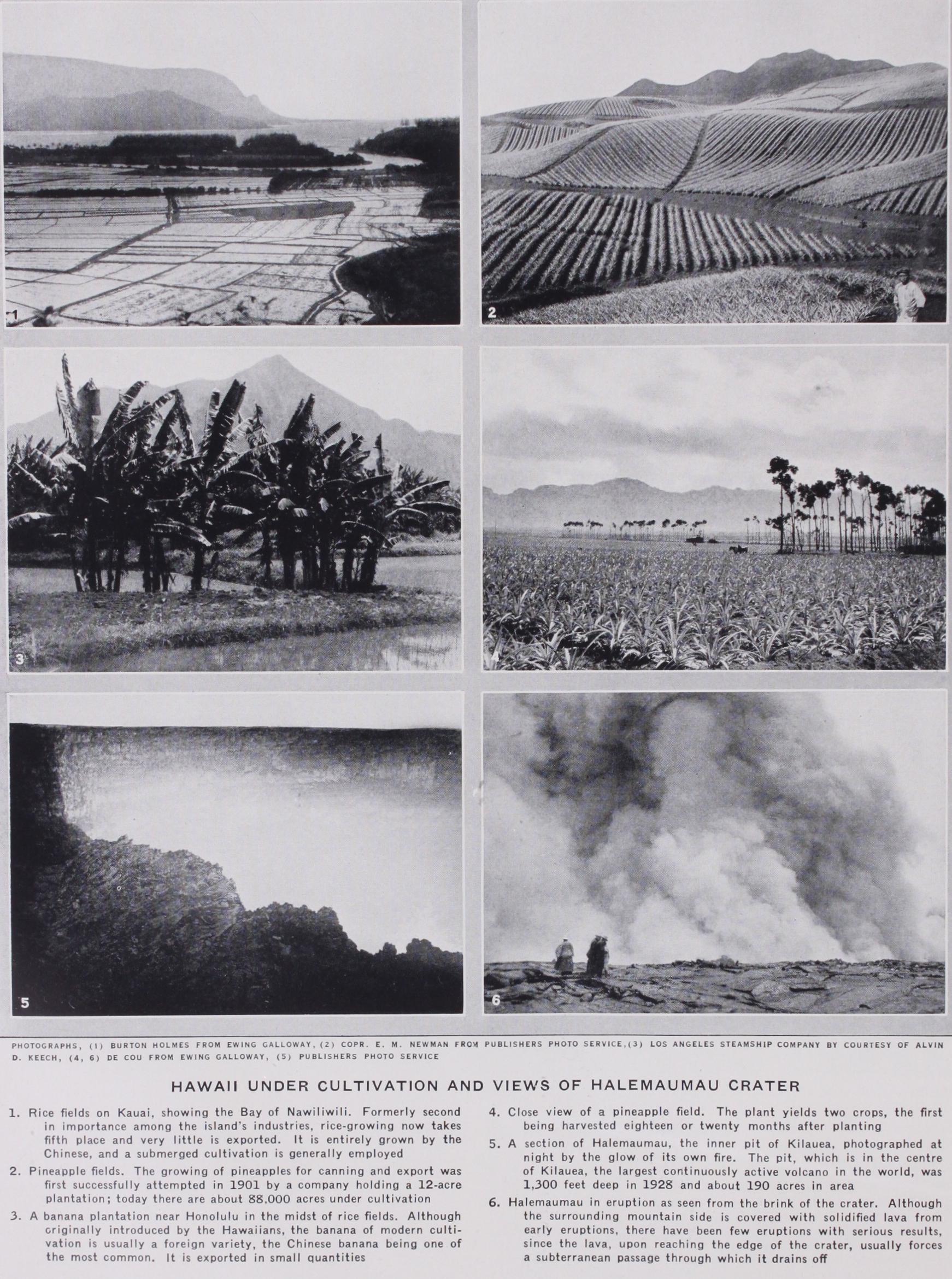

Lastly and easternmost, is Kilauea, with the largest and most spectacular of all active craters, an oval pit 4.14 sq.m. in area, with walls now soo ft. high—i,000 ft. a century ago. It is hardly a distinct mountain, for, although an independent volcano and older than Mauna Loa, it is merely a hole in the side of the latter at an elevation of 4,090 ft.; it is reached by motor in an hour, over 3o m. of concrete road through tropical forests from Hilo. Except for occasional flows over the floor of the main pit, visible activity has, for several decades, been confined to an oval inner pit, Halemaumau, 3,00o by 3,50o ft., and 1,3oo ft. deep in 1936. Operating in cycles, the lava rises until it overflows and breaks through some subterranean passage and drains out, only to begin the cycle again. During the i9th century and the early years of the 2oth the only flows of size outside the crater, and some distance from it, were those of 1823-40-68 and 1920-21, but small quantities of lava have erupted nearer in 1832-68, 1922 and 1923. Just before the last drop-out, in 1924, the lake of boiling molten lava covered about 5o ac., and when the lava fills the present enlarged caldera it will cover about 190 acres.

Only two explosive eruptions have occurred in historic times, those of Kilauea in 1790 and 1924, the earlier of which destroyed a division of a Hawaiian army. Earthquakes have been numerous and tidal waves occasional on the east coast of Hawaii island, but have done little damage, except in 1868, when, at the time of the lava flow of that year, a landslide i by 3 m., the so-called "mud flow," killed 31 persons; a tidal wave swept away several small villages, killing 46 persons, many houses were levelled, great cracks opened and the coast subsided some feet. All historic flows of Mauna Loa and Kilauea have been in regions of few or no habitations. That of 1826 covered the small village of Hoo puloa without loss of life. The lavas are of two kinds, pahoehoe, of smooth but wrinkled, shiny surface, and aa, exceedingly broken and jagged. Since 1911 a volcanic observatory has been main tained at Kilauea, and in 1916 the National Government created the Hawaii National park consisting of the Kilauea and Mauna Loa sections (245 sq.m. together) on Hawaii, and the Haleakala section (26 sq.m.) on Maui, to which was added in 1927 a strip (72 sq.m) connecting the first two sections. In the Kilauea sec tion, visited by 6o,000 persons annually, besides the active vol cano. there is much of interest, such as numerous other pit craters, sulphur banks, pumice beds, lava tubes, tree molds, lava trees, lava spatters in trees, stalactites, Pele's hair (Pele being the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes), tropical forests and birds and sulphur-steam baths.

Maui, Molokai, Lanai, Kahoolawe and Molokini

(the last uninhabited), probably once a single island, are now separated by channels only.6 to Io m. wide and 25o to 600 ft. deep. They are separated from Hawaii by a channel 26 m. wide and 6,192 ft. deep, and from Oahu by one 23 m. wide and 2,244 ft. deep.

Maui,

shaped like the head and bust of a woman, consists of two mountains (East and West Maui) connected by a low isthmus 6 m. wide. One of these mountains, Haleakala ("House of the Sun," 10,032 ft.), has on its summit the largest of all extinct craters, 20 m. around and 2,72o ft. deep; on whose floor of 19 sq.m. are 16 reddish cinder cones 400 to goo ft. high. The view from the summit is the grandest in the Territory. The windward side, a succession of gorges, rich in waterfalls and verdure, sup plies the water for the irrigation of the arid isthmus. It is tra versed by a wonderfully scenic drive. The other mountain, whose highest peak is Puu Kukui (5,788 ft.), being much older, is marked by deep radiating canyons such as the Iao or Wailuku valley (4,000 ft. deep), which is of marvellous beauty.

Molokai

likewise consists of two mountains, Mauna Loa (1,382 ft.) at the west end and Kamakou (4,958 ft.) at the east end, connected by a saddle 400 ft. high, both cut off by erosion on the windward side, so that the island is narrow and of fairly even width, 40 by 7 miles. The windward side, one of the most scenic coasts of the group, is a precipice, 50o to 4,000 ft. high, sheer from the ocean, the highest part of which is deeply in dented by magnificent valleys, and on a low peninsula, projecting from the base of which, near its centre, is the famous leper settle ment.

Lanai

(3,48o ft.) and Kahoolawe (1,472 ft.) are single moun tains, with cliffs on their southerly coasts exposed to the ocean, their northerly coasts being protected by Maui and Molokai. Cattle, sheep and goats have destroyed their forests except on the summit of Lanai. Recently, a pineapple company has acquired Lanai, constructed a harbour on the south coast and a model city in the centre of an extensive interior plateau, which it is reducing to cultivation. Molokini is a small crescent-shaped, barren, rocky island, 160 ft. high, the ruin of a volcano, between East Maui and Kahoolawe.

Oahu

was once two immense volcanoes ; erosion has made of it two parallel mountain ranges, one, Koolau (Konahuanui, 3,105 ft.) twice as long as the other and older, Waianae (Kaala, 4,030 ft.), connected by a saddle 800-1,200 ft. high, is roughly square in shape except for the extension of the Koolau range at the east, which is the longest in the group; both ranges are among the most rugged. Their outer sides are precipices with marginal lower country, 0-7 m. wide, at their bases, and are most scenic with lofty, fluted faces and broken sky-lines. There are many small, recent tufa, ash and lava cone craters, mostly coastal, especially in and about Honolulu. There are also elevated coral formations and evidences of earlier and greater subsidences. This island, though third in size and fifth in height, is important agriculturally. It contains the capital and trade centre on the lee coast of the east end and the land-locked Pearl harbour (ro sq.m.) at the crotch of the ranges (see HONOLULU) . The pictur esque sites of this island are easily accessible ; the most noted panoramic view being that of the windward side, which bursts suddenly on one upon arrival at the Pali (precipice), the only tra versable pass (1,20o ft.), 6 m. up a beautiful valley back of Honolulu.

Kauai,

separated from Oahu by a channel 63 m. wide and '1,232 ft. deep, is roughly circular in form, about 25 m. across, and con sists mainly of one mountain (Waialeale, 5,25o ft.), with marginal low lands except on the north-west. It is the oldest, most disintegrated, and most verdant of the larger islands, abounding in rivers and waterfalls. Its chief scenic attractions are the Grand canyon of the Waimea (3,00o ft. deep) in the south-west, com parable in colours and forms to the Grand canyon of the Colorado; the spacious Hanalei valley in the north ; and the Napali coast of precipices, 4,000 ft. high, on the north-west. This, with its canyons, fluted ridges, pinnacles, caves and waterfalls, is a most remarkable scenic region, though difficult of access.

Niihau,

separated from Kauai by a channel r5 m. wide and ft. deep, is a small island, 17 by 6 m., of which the east central third is a tableland 1,30o ft. high, with cliffs on the ocean side, and the remainder lowland of coral origin. The entire island is a sheep ranch privately owned. Lehua and Kaula, uninhabited, are crescent-shaped remains of tufa cones, respectively z m. N. and 23 m. S.W. of Niihau. Both are rookeries.

Climate.

The chief determinants are the prevailing north east trade winds from over cool ocean currents and the remarkably heights and contours of the land areas. The result is a climate cooler than elsewhere in the same latitude, equable temperatures abundant sunshine and absence of tropical storms. Mauna Loq and Haleakala form such barriers to the trade winds that thei leeward slopes have regular land and sea breezes. At times especially in winter, a "kona," or southerly wind, brings muggi ness and heavy rain. The windward slopes are cooler than the leeward, and the temperature falls about r° F for each 300 ft of altitude. There is no distinctly rainy or dry season, but usually more rain falls in winter than in summer. There is wid( variation in temperature, rainfall and wind for neighbouring localities. In 1905-36 the temperature varied on Hawaii island from 98° (lee shore) to 25° (at 6,685 ft.), and on Maui thf annual rainfall varied from 2.46 in. (at 90 ft. on the isthmus) to 562 in. (at 5,000 ft. only 81 m. distant), said to be the lowest and highest of all official records. The summit of Kauai has perhaps, the greatest average rainfall in the world. The greatest in 24 hours was 31.95 in. on windward Hawaii. At the Buren office in Honolulu, on leeward Oahu, the average annual rainfall was 28.6o in. and the mean annual temperature 74.6°, with a maximum of 88°, a minimum of 56°, a mean maximum of and a mean minimum of 69.5°. Four miles distant, at 1,028 ft. the average rainfall was 155.02 inches. Usually there is snow on Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa and sometimes on Haleakala.

Flora.

The isolation of Hawaii, its division into islands, the barriers of deep canyons and high precipices, and the wide variations in rainfall, temperature, wind, barometric pressure and geologic age of different localities, have evolved a flora that not only is exceptionally extensive for the area, but ranks first in the world in percentage of endemic genera and species. The num ber of species is over two-thirds that of New Zealand, which has 16 times the area. The percentage of endemics is 83, as compared with 34 in Samoa, 35 in Tahiti, 53 in Fiji and 75 in New Zealand. There are about goo species of flowering plants (over 30o being trees), 140 ferns (from the moss-like Trichomanes parvulunr, the size of a finger nail, to the stately tree-fern, Cibotiurn menziesii, 35 ft. high) , and also many hundred mosses, lichens, fungi and algae. The species are most numerous and best defined on the older islands; some are extremely localized. One endemic violet is confined to an area of a few square yards. In a 56 ac. oasis of rich soil surrounded by lava flows in the National park, there are 4o species of trees, several unique; one, when discovered, consisted of only a single specimen. From this a new genus was named, Hibiscadelphus, of which two other species have since been discovered, one of them a single specimen on Maui. Some species of trees vary from r ft. to 4o ft. and others from 3o to roo in height according to altitude. Several species of violets have woody stems 6 ft. high. Most developed are the Lobelioidae, of which there are over r oo species; these range from dwarf forms to palm-like giants 4o ft. high. This tribe is more developed only in South America. There are some 6o species of composites, a score of which are arborescent, such as the silversword (Argyro xiphium sandwicense). Hawaii, however, is poor in native palms, of which there is only one genus with ten species, and in orchids, of which there are only three insignificant species. There are but few trailing forest vines, though the luxuriant and brilliant-flow ered ieie (Freycinetia arnotti) and the glossy, fragrant maile (Alyxia olivae f ormis) , favourite for leis (wreaths) , are common. The forests are tropical and only a few trees shed their leaves seasonally. • Six botanical regions or zones are commonly treated more or less separately: strand, lowland, lower forest, middle forest, moun tain bog and upper forest, with subdivisions of dry and wet, windward and leeward, etc., each having in large measure its distinct flora, but with considerable overlapping. Above r ',coo ft. there is practically no vegetation.Hundreds of species have been introduced into the islands since their discovery by Europeans and about 25 were introduced anciently by the Hawaiians. Among the ancient introductions are the coco-nut, breadfruit; ohia ai or mountain apple (.Iambosa malaccensis) ; taro (Colocassia antiquorum, roots used for making a paste, poi, the principal food of the Hawaiians) ; sweet-potato; yam ; banana ; pia or arrowroot (Tacca pinnati fida) ; sugar cane; gourd ; awa and ti (Piper methysticum and Cordyline terminalis), roots used for making drinks, and leaves of ti, for wrappers, plates, etc. ; olona (Touchardia lati f olia, yielding exceedingly strong and durable fibre for fish nets, etc.) ; wauke (Brous sonetia pa pyri f era) , fibre used for making kapa or paper cloth; kukui or candle-nut (Aleurites moluccana), useful for candles, oil, dyes, paint, gum, food and medicine; snilo (Thespesia popul nea) and kou (Cordia subcordata), now almost extinct, and kamani (Callophyllum inophyllum), all three yielding beautiful wood valued for making calabashes and other dishes ; and hau (Paritionn tiliaceum), useful for making outriggers and rope and training over arbours for shade, noni (Morinda citrifolia), useful for dyes and perhaps ginger. Among the more common later in troductions are the avocado or alligator pear, mango, pineapple, orange and other citrons fruits, papaya, guava, coffee, grape, fig, poha or cape gooseberry, litchi, mulberry, tamarind, date, passion fruits, eugenias, cherimoya, custard apple and the Queensland nut.

Fauna.

Isolation and wide variations in local conditions have had much the same effect, though in lesser degree, on the fauna as on the flora, resulting in a high percentage of endemics and extreme localization. There is only one certainly indigenous land mammal, a small bat. Dogs, hogs, and perhaps rats and mice, were introduced anciently by the Hawaiians, and many domestic mammals have been brought in since Cook's discovery; some very early, as goats and English pigs by Cook in 1778; cattle and sheep by Vancouver in 1793, and horses by Cleveland in 1803. Spotted deer (Cervus axis) were introduced in 1867 and the mongoose in 1883, to destroy rats.There were about 125 species of birds, resident and migrant, of which, perhaps, a score are now extinct. On the inhabited islands the native birds are disappointingly few, as their habitats are mostly in the forests and on the heights. A striking example of bird evolution is found in the song-bird family (Drepanididae) with 6o species, all peculiar to Hawaii. Most prized for feather work were the yellow feathers of the now-extinct mamo (Dre panis pacifica) and nearly-extinct oo (Moho nobilis) ; the vermil ion, of the iiwi (Vestiaria coccinea) ; and the crimson, of the apapani (Himatione sanguinea). Very common are the brown elepaio (Chasiempis sandwicensis) ; the green-and-yellow amakihi (Chlorodrepanis spp.) ; and the ou (Psittirostra psittacea), the best Hawaiian songster. A wild goose, nene (Bernicia sandwicen sis), confines itself to dry areas. The birds most commonly seen on the lower and more open areas are exotics. Chickens were anciently introduced by the natives, and the later introductions include, besides various domestic fowls, the skylark, Chinese thrush, mynah, turtle dove, pigeon, linnet, blue-cheeked parrot, rice bird, English sparrow, pheasant, quail and California partridge.

The only native land reptiles are seven species of small skinks and geckos, commonly called lizards. There are no snakes, and the frogs and toads are introductions. Although there are several thousand species of indigenous insects, mostly endemic, they are not troublesome or destructive. The noxious forms are mostly introductions, such as the sugar-cane leaf-hopper and borer, rice borer, Mediterranean fruit fly, melon fly, Japanese beetle, horn fly, cutworms, army worms, termites, fleas and mosquitoes. Per haps no animal group has contributed more light on the subject of evolution than the 500 species of land and fresh-water shells of Hawaii, especially the beautiful tree shells (Achatinellidae). The exceptionally rich marine animal life includes more than 65o species of fish, many of which are fantastic in shape and colour. Among introduced fishes are trout, carp, black bass, catfish, goldfish and top minnows.

Industries.

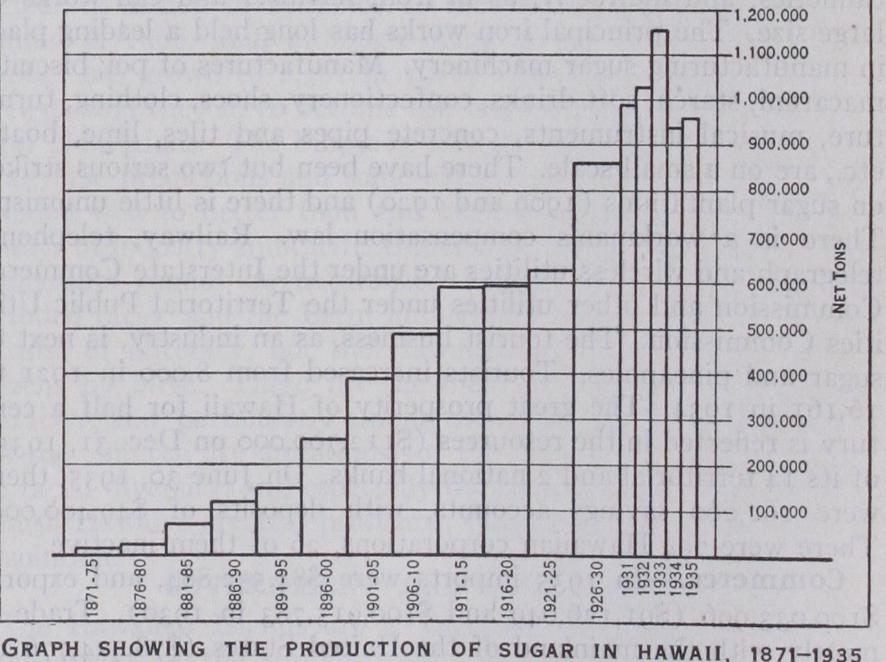

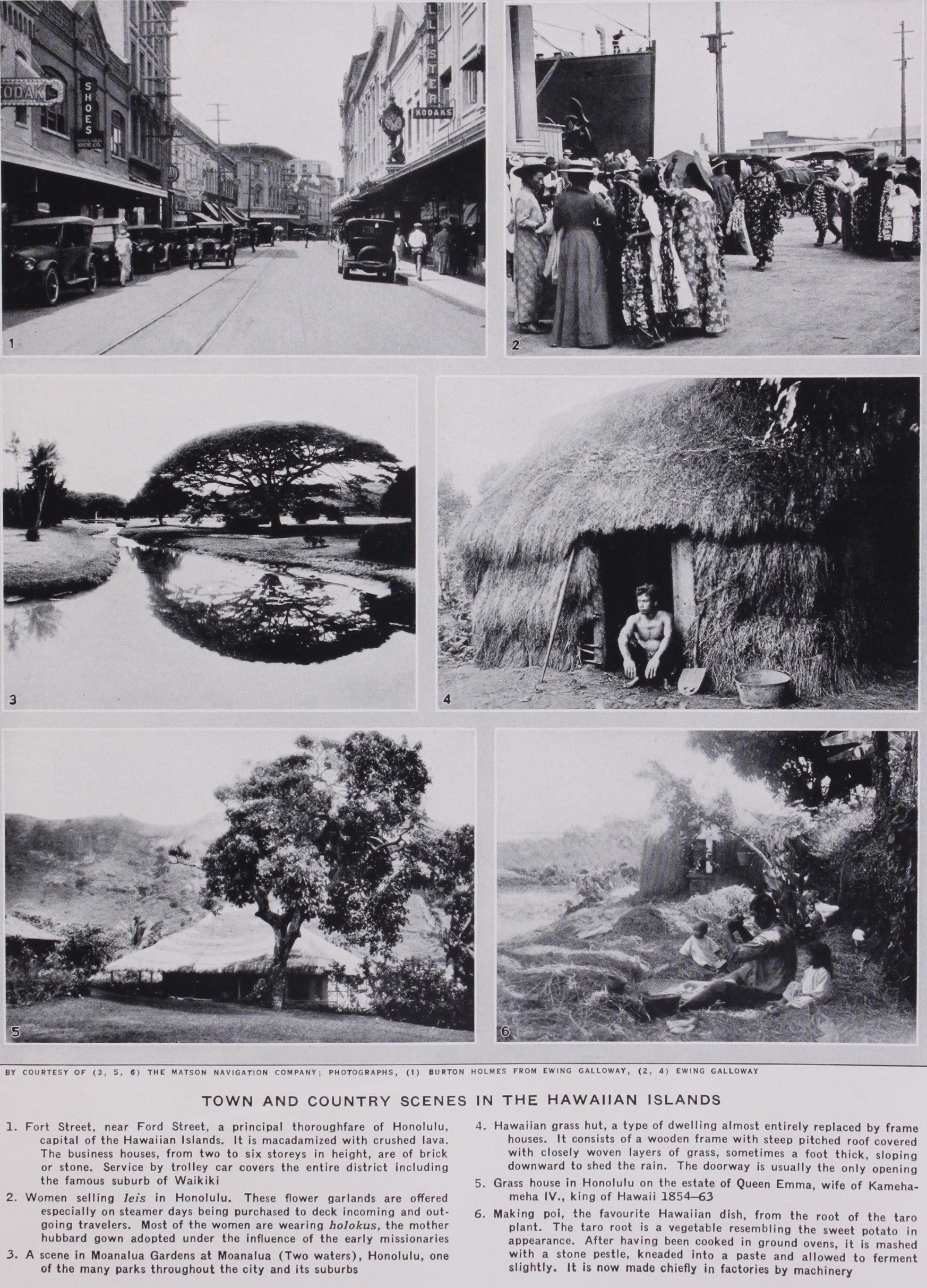

Sandalwood was Hawaii's first important com mercial product. The industry (1800-40) originated through fur traders, and was at its height during 1810-25. The wood was shipped to China, and the king and chiefs found the business so lucrative that they compelled most of the available population to get the wood from the forests, so that it was soon exhausted. But before that whaling (182o-8o) began. The vessels usually called twice a year for rest, repairs, supplies, storage or tranship ment of oil and whalebone and engagement of Hawaiians as sea men. The average annual calls during 1840-60, when the in dustry was at its height, averaged about 400. Whaling was also local. The discovery of petroleum (1859) and the destruction of whaling vessels in the Civil War and by the northern ice pack in 1871 lessened its importance. Hawaiians were excellent sea men; in 1846 about a fifth (3,000) of the young men of 15-30 were so engaged.The chief product of the islands has long been sugar. Small quantities were produced from 1802 to 1835, when the indus try really began, and yet the output had increased to only 13,036 short tons by 1876, when there was great impetus from the reciprocity treaty with the United States. It increased to 229,414 tons by 1898, the year of annexation, 517,090 in 1910 and 962,000 in 1935. For 25 years acreage and number of em ployees have remained fairly constant, but better methods have greatly increased the outpi't. The sugar and pineapple industries, especially have profited from scientific methods as applied through the sugar planters', pineapple planters' and U.S.A. experiment stations, University of Hawaii and Territorial Bureau of Agri culture and Forestry. The yield per acre averages 74 tons of sugar on irrigated and 5 tons on unirrigated land, with a maximum of 18 tons. The cane, however, requires from 14 to 3o months to grow and only a little over half the area (126,00o ac.), is harvested each year. Two or three crops at different stages grow at the same time. About half the area is irrigated—by conduits from mountain streams and pumping from artesian and surface wells. The irrigation system of one plantation cost nearly $6,000, 000. Before a field is harvested it is set on fire to burn off the leaves. Conveyance to the mills is by railway, flumes and over head trolley. The centrifugal drying process for sugar was in vented in Hawaii in 1851. All but one plantation ships sugar raw, mostly to their co-operative refinery in California. Corporations own the mills and raise most of the cane. Of the 45,000 or so unskilled employees about work by contract and are pro vided with living quarters, gardens, medical attendance and other advantages without cost.

The pineapple industry, a growth of this century, is second only to sugar in importance. The export of all companies has increased from 1,893 cases in 1903, to 9,000,000 (225,000,00o cans) in 1934. The area cultivated is about 88,000 acres. This industry, unlike sugar, had to create its market.

The live stock, coffee and rice industries have successively occupied second place. There are numerous ranches and dairies, many with thoroughbred stock—cattle, sheep, horses, hogs and poultry. The coffee industry, one of the oldest, is taking on new life. The coffee is of superior quality, known as "Kona" from the district on western Hawaii where most of it is raised. Rice is a waning industry. The banana industry is steady, though not large. Other industries which are still small or have had their day, but some of which have possibilities, are silk, cotton. tobacco_ rubber, vanilla, sisal, potato, wheat, flour, macadamia nut, etc. While Hawaii exports and imports a larger percentage of what it produces and consumes than most countries, there is neverthe less much subsistence farming, and several industries, such as live stock, fish, fruit and vegetable, figure largely in local trade. Little lumber is produced. Practically the only mineral products are building stone, lime and salt. Much has been done since 1850, and especially since 1895, to promote homesteading of public lands, not altogether successfully; but since 192o a new policy has been pursued, with greater success, under which permanent improvements are made in advance by the Government, settlers are selected with reference to their qualifications, long-time loans at low rates are made and instruction is given by specialists. Although Hawaii is essentially an agricultural country, the principal industries are such as require much manufacturing directly, as in sugar, pineapple, rice, coffee and fish mills and canneries, and indirectly, as in iron, fertilizer and can works of large size. The principal iron works has long held a leading place in manufacturing sugar machinery. Manufactures of poi, biscuits, macaroni, starch, soft drinks, confectionery, shoes, clothing, furni ture, musical instruments, concrete pipes and tiles, lime, boats, etc., are on a small scale. There have been but two serious strikes on sugar plantations (1909 and 1920) and there is little unionism. There is a workman's compensation law. Railway, telephone, telegraph and wireless utilities are under the Interstate Commerce Commission and other utilities under the Territorial Public Util ities Commission. The tourist business, as an industry, is next to sugar and pineapples. Tourists increased from 8.000 in 1921 to 16,161 in 1934. The great prosperity of Hawaii for half a cen tury is reflected in the resources ($112,700,000 on Dec. 31, of its 14 territorial and 2 national banks. On June 30, 1935, there were 162,00o savings accounts, with deposits of $49,400,000. There were 794 Hawaiian corporations, 26 of them inactive.

Commerce.

In imports were $84,552,884, and exports ($91,126,049 and $100,915,783 in 1930). Trade is mostly with the mainland of the United States ($78,924,776 of imports and $98,695,969 of exports in 1935), while $5,628,108 of imports and $1,338,027 of exports were with foreign countries. The exports comprised sugar, $58,680,000; fruits and nuts, mostly canned pineapples, $28,445,000; coffee, $614,000; pineapple juice, $5,647,000; molasses, $697,000; and hides, tallow, and wool, canned fish, bananas, rice, honey, etc. Imports from the mainland of the United States comprise a wide range of articles, while those from foreign countries are largely food stuffs from Japan, China, New Zealand and Australia, fertilizers from Chile and Germany, and jute bags from India.

Communications.

At Honolulu, besides model concrete wharves and sheds, there are dry-docks, electric freight-handling apparatus, automatic coal-handling plants, and oil tanks connect ing with the wharves by pipe lines. From 191 o to 1933 trans oceanic steamers, exclusive of naval vessels, army transports and coal-bunker vessels, increased from 5 7 o to 1,156, sailing vessels decreased from 257 to 7, the combined tonnage increased from approximately $4,300,00o to $9,962,00o in value, and passengers from about 90,00o to about 300,000, including through passengers. Twelve steamers engage exclusively in interisland traffic. There are many airports. In October 1936 a regular weekly air service by giant "Clipper Ships" with San Francisco and Manila was in augurated. In 1934 there were 223 m. of railroad, and 3,095 m. of concrete and macadam road on the islands. The larger islands have telephone systems. Honolulu has an electric street railway. Hawaii was the first country to establish wireless for commercial purposes. Besides a cable there are 4 powerful wireless plants.

Population and Immigration.

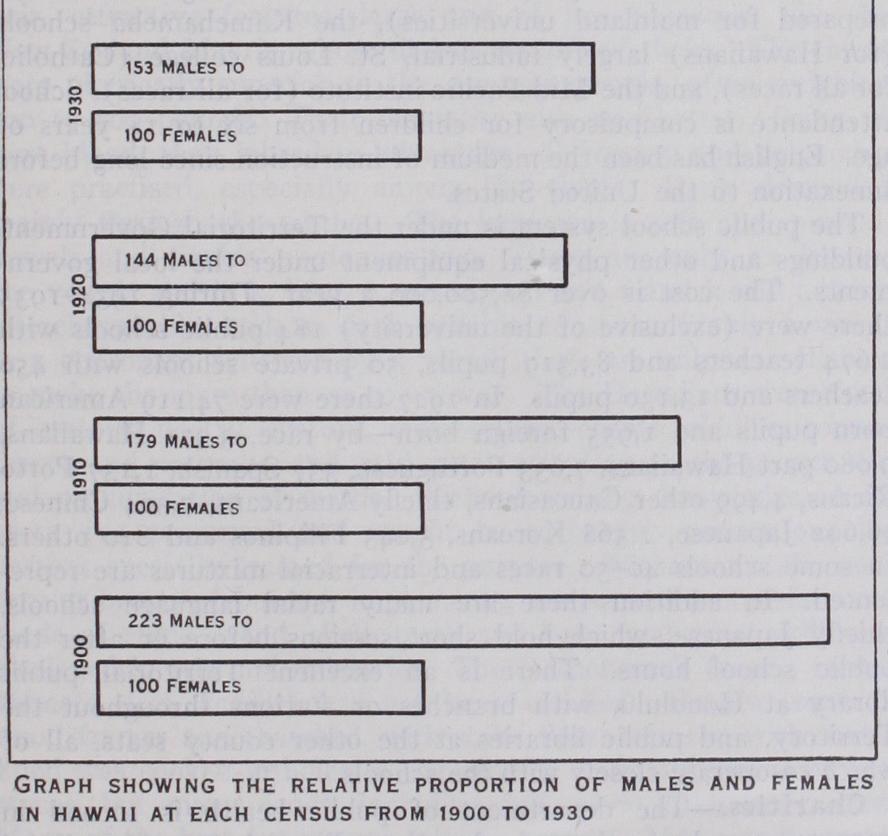

Since the discovery (1778), the population has changed from extreme homogeneity to extreme heterogeneity, due to decrease of Hawaiians during the first cen tury and immigration of others during the last half century. The discoverer estimated the Hawaiians at 400,00o but probably they did not exceed 300,000. Their decrease, due to many causes, has been rapid, but latterly at a diminishing rate. They now seem destined to disappear more through intermarriage with other races than through excess of deaths. The part-Hawaiians are increasing more rapidly than the pure Hawaiians are decreasing. The birth-rate of the former and death-rate of the latter are the greatest among all the races. In 1823 the missionaries estimated the Hawaiians at 142,050. The first census (1832) showed a total population of 130,313, including the few foreigners. That of 1872 showed low ebb in the total, 56,897 (51,531 Hawaiians and part-Hawaiians) . That of 1878, just after the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States began to stimulate immigration, showed 57,985, divided 47,508 and 10,477. That of 19oo, when Hawaii became a Territory, showed 1 S4,001, divided 37,656 (low ebb of Hawaiians and part-Hawaiians) and The U.S. census of 192o showed 255,912, divided 41,75o and 214,162. The 193o census found a total population of 368,336, or an increase of 43.9% in the course of a decade. The racial components were as follows : Hawaiian, 2 2,636 ; Caucasian Hawaiian, 15,632; Asiatic-Hawaiian, 12,592; American and north ern European, 44,895; Portuguese, 27,588; Spanish, 1,219; Porto Rican, 6,671; Filipino, 63,052; Chinese, 27,179; Japanese, 631; Korean, 6,461 others, 780. These include many crosses. The only cities with over io,000 populations were Honolulu with 13 7,582, an increase of 65.1 % and Hilo with 19,468, an increase of 86.6%. Immigration of large numbers of Chinese, Japanese and Korean adult males formerly produced highly abnormal ratios of aliens to citizens, males to females, singles to married and adults to children, but latterly, due to cessation of such immigration, deaths and departures, marriage, immigration of wives and births within the Territory, there has been a rapid tendency toward normality, retarded somewhat by similar immigration of Fili pinos.In 1927, 217,618 (65.27%) were U.S.A. citizens and 115,802 were not (including Filipino immigrants who were neither citizens nor aliens but owed allegiance to the United States). Native-born constituted 41 • i % in 1900, 51.1 % in 1910, (including the newly-arrived Filipinos) in 192o, and 81.4% in 1930. Males fell from 69.1% in 190o to 64. 1 % in 1910, and to 59 • I % in 19 20, in cluding Filipinos, but rose again to 60.5 % in 1930. Increase of population except of Americans and Filipinos, is now mainly through births. Departures of most others exceed arrivals. In 1932 the birth-rate was 28.19 and the death-rate 9.76 per i,000. The birth-rate was highest among Asiatic-Hawaiians, followed by Caucasian-Hawaiians and the Japanese, and lowest among Ameri cans and Northern Europeans. The death rate was highest among Hawaiians followed by Caucasian-Hawaiians, Filipinos, Asiatic Hawaiians, Koreans, Japanese, Spanish, and lowest among Ameri cans and northern Europeans. Illiteracy in 193o was 15.1 %, as compared with 18.9% in 1920. Percentage of illiteracy by races was: Filipino, 38.5; Puerto Rican, 3 2 .o ; Korean, 17.6; Spanish, 16.4; Chinese, 15.7; Japanese, 12.7; Portuguese, 9.7 ; Hawaiian, 3.4 ; Asiatic-Hawaiian, 0.9 ; Caucasian-Hawaiian, o.6 ; other Cau casian, 0•3. There is a strong tendency toward racial intermarriage. It is difficult to classify by races because of the mingling.

Experiments in Immigration.

On the "cognate race" plan, Polynesians from the South Sea islands were introduced in 1859, 1865, 1868-71, 18i4 and 1878-85, 2,454 in all, but they were disappointments, both as labourers and prospective citizens, and most of them were returned to their homes. On the "desirable citizen" plan, Caucasians other than Latins were introduced, as Americans in 187o and 1898, Norwegians in 1881, Germans in 1882-85 and 1897, Galicians in 1898, Russians in 19°9-14 and Poles in 1914, about 4,45o in all, but most of them soon outgrew the status of unskilled labourers or left the islands.

Attention was then directed chiefly to the Latins, particularly the Portuguese. Consequent upon the pressing demand for labour occasioned by the Reciprocity Treaty and after investigation of the relative merits of immigrants from many countries, I o, 798 Portuguese were brought from Madeira and the Azores in 1878-90 and 337 in 1899. They proved to be industrious, thrifty and law abiding. They brought their families and most of them remained and multiplied. In 1906-13, 5,196 more were introduced, many from Portugal. Simultaneously 7,695 Spanish were brought from Malaga, but most of these have left, and, although many Portu guese also have left, those in the Territory had increased to 28,417 by 1927. In 1898, 255 Italians were introduced and in 19oo–oi about 5,00o Porto Ricans. Most of the latter remained and, contrary to first indications, the majority have developed well and increased to 6,572. About ioo negroes and their families (190 i) and about 50o Hindus (I 9o8r I I) were introduced, most of whom soon left. Aside from the Portuguese,—the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and Filipinos have constituted the bulk of the labour immigrants. The Chinese came first (1,632 in 185 2-67) ; then, opposition having developed, 148 Japanese were introduced in 1868, but, the Japanese Government objecting, no more were brought in and the Chinese continued to come (2,819 in 1868-7 7 ) when, in 1878, the immigration of Portuguese began, but not to the exclusion of the Chinese, who continued to come unassisted in large numbers (20,791 in 1878-85). The Chinese became so numerous that restrictive measures were applied in 1883 and attention was again turned to Japan. Chinese immigration almost ceased, the total for 1886-99 having been only 6,129, of whom 5,241 came in 189 , just before the Federal Chinese exclusion laws were extended to Hawaii upon annexation. Japanese came in large numbers, at first assisted and then unassisted, 65,034 during of whom 19,908 came the last year, fearing that such immigration also might be inhibited. Many went from Hawaii to the mainland, the arrivals having been 96,092 and the departures, to the mainland and Japan, 92,221 during I 9oo–I 5, but after the "Gentlemen's Agreement" of 1907 between the United States and Japan the arrivals were largely women, which resulted in rapid increase through births. Opposition on the mainland led to Japanese exclusion in 1924. The Chinese immigrant population resident in the islands decreased from 25,762 in 190o to 21,674 in I 910, but the total of both immigrant and Hawaiian-born Chinese increased, through excess of births over deaths and de partures, to 23, 507 in 191 o and 27,179 in 1930. The Japanese increased from 61,115 in 190o to 79,675 in 1910, 109,274 in 1920 and 139,631 in 1930. Koreans to the number of 7,859 came in 1903-05, but there were only 4,533 in 1910 and 4,95o in 1920; since then they have increased through births to 6,461 in 1930.

Finally, largely because of the enactment of Federal laws pro hibiting assisted immigration from foreign countries, the sugar companies turned to Filipinos as the only available source, be ginning in 1906, and, although many go to the mainland, the number has grown to 2,361 in 1910, 2I,o31 in 192o and 63,052 in 1930, and they have become the largest racial element on the sugar plantations. The Filipinos, like the Porto Ricans, contrary to adverse predictions and some early disappointments, have re sponded well to better food and health conditions and training in ways of industry and thrift. Under the Federal laws the oriental immigrants cannot be naturalized because they belong to the excluded races, and the Latin immigrants usually cannot qualify because of illiteracy, but the Hawaiian-born children of all are citizens by birth. These for the most part display ability and character, and, particularly among the orientals, both the parents and the children are ambitious for the latter's education. While the racial diversity, and especially the large number of Japanese, furnish Hawaii's greatest problems, they appear to be in process of solution.

The Hawaiian Islands are a Territory, an integral part, not a possession, of the United States, governed under an Organic Act, effective from June 14, 1900. The Federal officers are a delegate to Congress, elected for two years, who may introduce bills and debate but not vote, two judges of a Federal district court and a U.S.A. attorney and marshal, appointed for six years by the president with the consent of the Federal Senate, and vari ous officials of the Treasury, Post-office, Agriculture, Commerce and Interior departments. The Territorial legislature, which meets biennially, consists of a senate of 15 members elected, seven or eight at each biennial election, for four years, and a house of representatives of 3o members elected for two years. The presi dent, with the consent of the Federal Senate, appoints for four years the the secretary, who acts as governor in the absence or disability of the latter, the chief justice and two asso ciate justices of the supreme court and the eight judges of the five circuit courts. The governor, with the consent of the Terri torial senate, appoints for four years, and with like consent may remove, the attorney-general, treasurer, auditor, commissioner of public lands, superintendent of public works, superintendent of public instruction, surveyor, high sheriff, and, for various terms, all members of boards and commissions, among which are those of health, harbours, public instruction, public utilities, agriculture and forestry, fish and game, farm loan, pension, uni versity regents, registration of voters and inspectors of election.

Hawaii, having previously been an independent sovereignty, is the most highly organized Territory created by Congress and the only one to which has been given the administration and revenue of its public lands. The chief justice appoints for two years one or more district magistrates for each of the 27 district courts. Certain designated circuit judges serve also as judges of the land court (Torrens), the court of domestic relations and the juvenile courts. Equity and law are kept distinct but with sim plified procedures. Appeals may be taken from the Federal dis trict court and, when a Federal question or a value in excess of $5,000 is involved, from the Territorial supreme court to the Federal circuit court of appeals of the ninth circuit. Local governments were first created in 1905. These are (1936) the city and county of Honolulu, comprising the island of Oahu and all small islands not included in any other county and hence extending 1,350 m. W. and I,Ioo m. S. of Honolulu, the city and county seat ; county of Hawaii, comprising the island of that name, county seat at Hilo ; county of Maui, comprising the islands of Maui, Molokai (except the leper settlement), Lanai and Kahoolawe, county seat at Wailuku; county of Kauai, com prising the islands of Kauai and Niihau, county seat at Lihue; county of Kalawao, comprising the leper settlement. Each in cludes also the small islands within 3 m. of the shores of the larger ones. Each, except Kalawao, which is only an inchoate county under the board of health, has a board of supervisors, sheriff, clerk, auditor, attorney and treasurer elected for two years. Honolulu has also a mayor. Territorial and local officers and the Federal judges, attorney and marshal must, in general, be citizens of the United States and have resided in the Territory one to three years next preceding election or appointment.

The qualifications of voters are citizenship, residence of a year in the Territory and three months in the district, age of 21 years, ability to speak, read and write the English or Hawaiian language, and registration, which is permanent except that if one fails to vote at any election his name is struck out and he must reregister in order to vote. Absent seamen may vote, but those in the army or navy may not. Except Kauai supervisors and the Kalawao sheriff, all Territorial and local elective officers are elected at large or from multi-member districts. Direct primaries have been in operation since 1913 and woman suffrage since 1920. The political parties are the Republican and Democratic, the former preponderating. Citizenship by birth and naturalization are governed by the Federal Constitution and laws. During the gen eral election of 1930 the registered voters numbered 52,149, as follows: Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian, 19,858; Caucasian, 19,225 (11,114 Anglo-Saxon and 8,1i I Latin, mostly Portuguese) ; Ori ental, 11,419 (7,057 Japanese, 4,402 Chinese). Over 85% of those who registered voted.

Finance.

On June 3o, 1935, the Territory had a cash balance of $1,413,938. The bonded indebtedness of the Territory on June 3o, 1936 was: of the Territory, $33,141,000 (14. to 41%); [the bonded indebtedness is limited by act of Congress to Io% of the assessed value of real and personal property in 1936)] ; of the county of Hawaii, $937,000; of Mavi county, and of the city and county of Honolulu, $3,415,948 ( to 5%), and $1,446,726 of improvement. District bonds (5 and 6%), payable solely by the property, benefited. All such debts have been incurred since 1910 for public improvements, for which also much current revenue has been expended. For the year ended June 3o, 1936, the revenue was $15,986,797; of which was derived from special taxes, $2,764,566 from the general prop erty tax, $2,636,759 from business excises, $1,191,846 from inter est, etc., $593,896 from rents and leases, and $3,656,219 from all others. Expenditures in 1936 were $12,533,768, the chief item be ing education, $5,685,619. The assessed value of property was as compared with $150,268,467 in 1910. The Terri tory has also paid in taxes to the Federal government of the United States an average of about $6,5oo,000 a year during the last decade—ranking each year above eleven to fifteen States. In 1925 the legislature provided for a Territorial budget system, a pension system for Territorial employees, and a uniform account ing system for the Territorial and local governments.

Education.

A dozen years after the arrival of the first mis sionaries in 1820 there were 90o schools with 53,00o pupils (4o% of the population, mostly adults) ; a dozen years later about 8o% were literate. In 1824 the regent and chiefs prescribed schools and compulsory attendance. In 1831 and 1834 there were founded two higher institutions for training teachers and religious assist ants, which were also largely manual and industrial training schools, said to be the first of the kind established in what is now the United States. It was his knowledge of these industrial schools that led a missionary's son, Gen. Samuel C. Armstrong, to establish Hampton institute in Virginia. His father was min ister of public instruction 1847-60. In the '3os and '4os pupils came from Spanish California, Kamchatka and other Pacific islands to attend an English-taught school opened in Honolulu in 1833.The educational system includes all grades from kindergarten to university, as well as a normal school and schools for the physically defective, feeble-minded and juvenile delinquents and evening classes. Much attention is given to agricultural, trade and industrial vocational work (including part-time schools), home economics and medical, dental and nutritional needs. The university (about i,000 students) maintains an aquarium and marine biological laboratory, conducts extension work and renders important service in industrial experimental and research work. Prominent among private schools are Oahu college (I,000 stu dents) founded in 1841 (where most of the Anglo-Saxons are prepared for mainland universities), the Kamehameha schools (for Hawaiians) largely industrial, St. Louis college (Catholic, for all races), and the Mid-Pacific institute (for all races). School attendance is compulsory for children from six to 14 years of age. English has been the medium of instruction since long before annexation to the United States.

The public school system is under the Territorial Government, buildings and other physical equipment under the local govern ments. The cost is over $8,500,000 a year. During 1934-1935 there were (exclusive of the university) 184 public schools with 2,674 teachers and 83,319 pupils, 50 private schools with 450 teachers and 13,130 pupils. In 1927 there were 74,119 American born pupils and 1,955 foreign born—by race, 3,971 Hawaiians, 9,08o part-Hawaiians, 7,633 Portuguese, 337 Spanish, 1,137 Porto Ricans, 4,499 other Caucasians, chiefly Americans, 7,304 Chinese, 36,692 Japanese, 1,568 Koreans, 3,043 Filipinos and 810 others. In some schools 4o-5o races and interracial mixtures are repre sented. In addition there are many racial language schools. chiefly Japanese, which hold short sessions before or after the public school hours. There is an excellent Territorial public library at Honolulu, with branches or stations throughout the Territory, and public libraries at the other county seats, all of which co-operate closely with the schools.

Charities.

The department of public health is second in importance only to that of education. Physicians are employed or subsidized for the benefit of all, however indigent or remote from population centres. The principal institution is the Molokai leper settlement, with its auxiliary hospital in Honolulu. Formerly emphasis was laid on isolation, but since 1909 it has been placed on treatment, and the number of lepers has greatly decreased. At one time there were over 1,200 lepers in these institutions and many at large; in 1936 there were 527 confined and few at large. There are many charitable and welfare institutions throughout the islands.

History Before Discovery.

Polynesia was probably the Iast habitable area to be occupied by man. The Polynesians, although of similar features, language, customs, religion and tra ditions, are not a pure race. They are supposed to be mainly of Aryan origin, with infusions of other bloods, and to have come from Asia by way of the Malay peninsula and Java, and thence from island to island by various routes in their migra tions eastward, northward and southward, and to have reached Hawaii, probably from Samoa, about A.D. 500. The next five centuries were for the Hawaiians a period of seclusion and peace. Then, in the 11th to 13th centuries, a time of activity through out Polynesia, intercourse was resumed with Tahiti, Samoa and other islands over 2,000 M. to the south by huge sailing canoes. During this period many chiefs, who intermarried with Hawaiian reigning families, and priests came to Hawaii, both classes be came powerful and the severity of tabus and frequency of human sacrifices increased. Then followed another long period of isola tion, the last centuries of which were full of wars and rebellions —the result of pressure of population, rapacity of the nobility and dynastic ambitions and jealousies.Feudalism grew up much as it did in mediaeval Europe and from much the same causes. The unit of land, the ahupuaa, usually extended from the shore to the mountain top, with rights in the adjoining sea waters, so that the occupants had the means of supplying all their wants—the sea for fish, the littoral for coconuts, the valley for taro, their principal food, the lower slopes for sweet potatoes, yams and bananas and the mountain for wood. The next subdivision was the ili, either subservient to the ahupuaa or independent. Within these. were small areas, kuleanas, occupied by the common people, who also had certain rights of fishery, water and mountain products. Besides open sea fisheries, there were stone-walled fishponds, some now a thousand years old, built semi-circularly from the shore. Taro was raised in terraces flooded by conduits from streams. Elabo rate systems of water rights were evolved. A conqueror or a successor king often redistributed the lands.

The Hawaiians were a brown race, with straight or wavy black hair, attractive features, large and of fine physique, like the New Zealand Maoris, whose dialect resembled theirs. The chiefs were physically superior to the common people, often weighing 30o to 500 pounds. Their mentality also was better. Being of pure blood, they inbred to advantage. Polygamy and polyandry were practised, especially among the chiefs. Rank descended mainly through the mother. The language is soft and musical, vowels and liquids predominating. There are only 12 letters, the vowels and h, k, 1, m, n, p and w, 1 and r and k and t being interchangeable, as each syllable consists of only a vowel or a consonant followed by a vowel, there are only 4o syllables to make the more than 20,000 words. The Hawaiians were fond of oratory, poetry, history, story-telling, chants, riddles, conun drums and proverbs, and paid much attention to the proper use and pronunciation of words. Without writing, knowledge of all sorts was preserved and taught to successive generations by persons specially trained for the purpose. Without metals, pot tery or beasts of burden, implements, weapons and utensils were made of stone, wood, shell, teeth and bone, and great skill was displayed in arts and industries. The feather-work (capes, robes, helmets, leis, kahilis) has not been excelled. Houses were of wood frames and thatched, with stone floors covered with mats. Food was cooked in holes in the ground, imus, by means of hot stones, but many foods, including fish, were often eaten raw. Many of the best foods were tabu to women. Men usually wore only a inalu or girdle and women a skirt of kapa or paper cloth or leaves or fibre, though both sometimes wore mantles thrown over the shoulders. Canoes were outrigger or double, sometimes ft. long. They have hardly been surpassed as sailors, fish ermen or swimmers. They were skilful navigators, knowing stars, winds and currents. Their year began on Nov. 20 and consisted of 12 lunar months with occasionally an intercalary month. They had remarkable knowledge of animals and plants and were great warriors, using spears, javelins, clubs and slings, but no shields or bows, the latter being small and used only for shooting rats and mice for sport.

They excelled in athletics, in which there were frequent con tests, even between champions of different islands, in surf boarding on the crests of waves, swimming, wrestling, boxing, spear-throwing (at each other), coasting down permanently pre pared courses standing on narrow sleds, bowling, foot-racing, etc. Surfing has now become a favourite sport for others as well as Hawaiians. They gambled much and made narcotic and fermented drinks of the awa and ti roots, but not distilled liquours. They were fond of music, vocal and instrumental, and had percussion, string and wind instruments, including a nose flute but no mouth flute. The ukulele is of Portuguese origin, developed and popularized by the Hawaiians. Their dances were largely the notorious hula of many varieties, the better forms of which have latterly become popular with others. They loved flowers, which they wore much in leis or wreaths about necks and hats. This has become customary with the whites, especially on arrivals and departures of steamers and on May day. They tattooed little. Their proverbially courteous, generous, hospitable spirit has affected the remainder of the population.

There were four principal gods, Kane, Kanaloa, Ku and Lono, and innumerable lesser gods and tutelar deities. Animals, plants, places, professions, families, all objects and forces had their gods or spirits. Temples of stone and idols of wood abounded and hardly anything was undertaken without religious ceremonies. On important occasions there were human sacrifices. There was a vague belief in a future state. Priests and sorcerers were potent. There were "cities of refuge" to which one might flee and be safe. Cannibalism was unknown but infanticide prevalent. The political and religious systems were closely interwoven.

During the last period before the discovery, although there were occasional bright intervals under highminded kings, and notwithstanding that there was so much that was praiseworthy, in general, the nobility and priesthood became more and more aristocratic and tyrannical, the common people more and more degraded ; destruction of life was frightful ; property was inse cure; there was little encouragement for industry; the laws, chief among which were the intricate and oppressive tabus, bore heavily upon the masses, especially the women, and their admin istration became largely a matter of arbitrariness and favouritism.

History After Discovery.

Although foreigners other than polynesians early arrived in Hawaii as castaways not to return to the civilized world, the theory, until recently accepted, that the Spaniard Juan Gaetano discovered Hawaii in 1555 (or 1S4 2) is now exploded, and Captain James Cook, the great English navi gator, is regarded as the discoverer beyond dispute. Cook first landed at Waimea, Kauai, on Jan. 18, 17 78. The natives thought him the god Lono. On his return the next year, he was killed, after a period of friendly relations with the natives, on Feb. 14, 1779, in an affray at Kaawaloa, Hawaii, where a monument to him now stands.

Then

followed a period of contact with pre-missionary whites (1778-182o), a period of political consolidation and religious disintegration. Kamehameha I., the most striking figure in Hawaiian history, came to the throne of one of the then four kingdoms in 1782, and, equipping himself better than his foes with vessels, firearms and aids, foreign and native, succeeded by in conquering all the islands except Kauai and Niihau, and in securing the latter by cession in 181o. Having effected con solidation, he organized the Government, checked oppression encouraged industry and suppressed crime, until, as it was said, "the old, men and women, and little children could sleep safely in the highways." He thwarted Russian designs upon the islands (1815-16) and eliminated Spanish pirates (1818) . It was in this period that the sandal-wood trade developed. In 1804 an epi demic, probably cholera, destroyed much of the population.Benign foreign influences were exerted by such voyagers as Vancouver , Cleveland (1803) and Kotzebue (1816), and such residents as John Young and Isaac Davis, captured (179o) boatswain and mate, and Don Francisco de Paula Marin, immigrant (in 1791) from Andalusia, who introduced useful plants and animals and inculcated higher ideals. But baleful foreign influences were exerted by numerous Botany bay con victs, pirates, buccaneers, beachcombers, adventurers and others, who introduced the art of distillation, fire arms, venereal dis eases and vices of all kinds.

Kamehameha treated foreigners well but combated their vices. Indulging a little at first, he later abstained from the use of liquors and ordered the destruction of distilleries. Having un successfully sought to obtain teachers of Christianity, he ad hered to the Hawaiian religion and enforced strict observance of it, but with lessening severity. The .last human sacrifices were in 1807. However, foreign influences undermined faith in the old religious systems, and shortly after his death (May 8, 1819), these were abolished (about Nov. 1, 1819) under the leadership of his favourite queen, Kaahumanu, and his queen of highest rank, Keopuolani—not, however, without a bloody battle (Dec. 20, 1819) between the progressives and conservatives. Thus, union under a single Government, the establishment of peace and order, and the dissolution of the old politico-religious bonds, pre pared the way for new social forces.

The Third Period of Hawaiian History

began with the ar rival of the first company of missionaries from New England on March 31, 1820. Fourteen other companies followed during the next 35 years, in all over 15o men and women—ministers, teachers, physicians, printers, farmers and business men. They introduced the church, the school and the press. The Hawaiians were most eager to learn. By Jan. 7, 1822, the missionaries had learned the language, reduced it to writing and begun printing the first text-book. Two months later the first printed law was issued. By 1840 5o books had been printed. In 1834 two Ha waiian newspapers were published. An English newspaper, founded in 1843, is still published. The first press on the Pacific coast was imported from Hawaii into Oregon in 1839. The New Testament was completed in 1832, the Old in 1839, the dic tionary in 1865. Of great assistance was William Ellis, English missionary in Tahiti, who visited Hawaii in 1822. While Chris tianity soon came to be regarded as the national religion, and churches were well attended everywhere, little interest was taken in it as a personal matter until 1829, when there were 185 church members, of whom 117 joined that year.Interest culminated in the "Great Revival" of a decade later, which added a fifth of the population. The first convert (1823) was Keopuolani, head queen of Kamehameha, mother of the next two kings and highest chief by blood in the nation. Indeed the chiefs, especially the females, led in embracing and supporting the new religion and learning. Kaahumanu, Kamehameha's favourite queen, was converted in 1825 and was thereafter known as the "New Kaahumanu," as strong for good as she had theretofore been haughty and cruel, and of the ten who joined the church in 1826, nine were chiefs, including Kalanimoku, known as the "Iron Cable." Kaahumanu and Kalanimoku were the strongest characters in the nation.

Women in Power.

Kamehameha I., recognizing the weak nesses of his son, Liloliho (Kamehameha II.), had appointed Kaahumanu to be his kuhina nui, or premier, with power almost equal to that of the king. She acted as regent when the king and queen visited England in 1824, and, they having died there of the measles, she continued as regent until her death (1832), the new king, Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III.) being then an infant. Kalanimoku had been prime minister and treasurer to Kamehameha I. and continued such under Kaahumanu until his death in 1827. Kaahumanu was succeeded as kuhina nui by Kinau, daughter of Kamehameha I. and mother of Kamehameha IV. and Kamehameha V., until her death in 1839, and then by Kekauluohi, mother of King Lunalilo, until her death in These noble women, Keopuolani, Kaahumanu, Kinau and Kekau luohi and others, like Kapiolani, whose courageous defiance of Pele (1824) was sung by Tennyson, and Bernice Pauahi Bishop, who twice refused the crown and gave (1884) all the Kame hameha lands to found schools for her race, would have done credit to any nation.The first score or so of years after the arrival of the mis sionaries was a crucial period, not so much because of the in herent difficulties of civilizing and christianizing a barbarous and pagan race as because of the opposition of whites. This oppo sition came not only from the beachcombers and grog-shop keepers, but, more dangerously, from British, French and Ameri can consuls and naval officers. They opposed the laws against licentiousness and drunkenness, slandered the missionaries, made unjust claims against the Government, insisted that they were not subject to Hawaiian laws, attacked with arms the homes of missionaries and chiefs, aimed at the overthrow of the Govern ment; the British consul claimed that the islands had become British territory.

Democratic Sovereigns.

This period was not, however, without bright spots in helpful foreign influences both from resi dents and from such visitors as Lord Byron of the British navy, cousin of the poet, who brought back the bodies of the king and queen in 1825, and Capt. Jones (1826) and Capt. Finch (1829) of the American navy, the former of whom negotiated the first treaty entered into by Hawaii. Whaling had become active in 1820 and the sugar industry in 1835. There was trouble over Catholic priests who came in 1827; they were banished in 1831, on the ground, among others, that they were reviving idolatry which had been abolished in 1819, but returned in 1836-37. Meanwhile, due to increasing complications with foreigners, growth in liberal and humane sentiments on the part of the chiefs and in realization of their natural rights by the common people, a conviction arose of the need of a better defined and more advanced form of Government as a condition of peace, progress and independence.Hence, after vain attempts to secure from New England teach ers of the science of government, the missionaries were induced to detach one of their number, W. Richards. He rendered notable service to the Government as did two other missionaries, G. P. Judd and R. Armstrong, similarly detached later. After hearing a course of lectures on government (1839) delivered to the king, chiefs and leading commoners, the king promulgated the Declara tion of Rights, called Hawaii's magna charta, June 7, 1839, the Edict of Toleration, June 17, 1839, and the first Constitution, Oct. 8, 1840. The first compilation of laws was published in 1842. The Catholics began their cathedral in 1840, and ever since, through churches and schools, have done much good work. Contrary to the usual course of history, in Hawaii democratiza tion evolved from the top downward rather than from the bot tom upward.

But troubles with foreigners were not at an end. French naval officers in i839, 1842, 1849 and 1851 made unjust demands, the first and third times accompanied by force. A British naval officer took possession in 1843 and held it until the flag was re stored by higher authority. After the ceremonies, the king, ad dressing his people on the means of preserving independence, used the expression "Ua man ke ea o ka aina i ka pono" ("The life of the land is perpetuated by righteousness"), which has since been Hawaii's official motto. Diplomatic missions secured recognition of independence from the United States in 1842 and England and France in Further troubles with foreigners, and especially the outrageous French demands of 1849 and 1851, led to other diplomatic mis sions, and in the latter year a secret proclamation putting the islands under the protection of the United States. The French, having learned this, retracted and the United States declined the protectorate, but, as a result of further troubles and dangers, within and without, including threatened filibustering from Cali fornia, and the "manifest destiny" sentiment awakened in the United States by the acquisition of the Oregon Territory and California, negotiations were opened in 1854 for annexation to the United States but were terminated by the death of the king. The troublesome foreign representatives were removed and fairer treaties entered into. Mormon missionaries first came in 185o, and that church now has a large membership and a magnificent temple and is doing good work.

New Codes.—Encouragement of immigration began in 1852 and has continued ever since. A small-pox epidemic in 1853 numbered its victims in thousands. Meanwhile, after the adoption of the crude Constitution of 184o, every effort was made to organize and perfect the Government. An able lawyer, John Ricord, was appointed attorney-general in 1844 and made a famous report to the legislature of 1845, as a result of which he was requested to draft comprehensive organic acts, which were enacted in 1846-47. W. L. Lee was appointed chief justice in 1846. He was chief drafter of the penal code of 185o, the more modern Constitution of 1852 and chief compiler of the civil code of 1859. Action was taken in 1845 and subsequent years by which the old feudal tenures were changed to allodial, and the interests of Government, Crown, chiefs and common people were severed and all claims adjudicated by a board of which Lee was chairman. R. C. Wyllie, a Scot, was minister of foreign affairs 1845-65. For able and untiring service, Lee, Wyllie and Ricord are among the outstanding personages in Hawaiian history. A tower of strength was Kekuanaoa (father of Kamehamehas IV. and V.), governor and judge of Oahu. The long and fruitful reign of the liberal-minded Kamehameha III. ended on Dec. 15, 18S4. Hawaii had become a civilized and christianized country with constitutional Government, highly creditable legislative, executive and judicial branches, personal and property rights secure, allodial tenures, modern industries, the respect of other nations and independence assured.

The next two kings, high-minded, educated and travelled, Kamehameha IV. (1854-63) and V. (1863-72), feeling that the Government had become democratized too rapidly and that American interests were becoming too preponderant, were slightly reactionary and pro-British. The former and his consort, Queen Emma, are remembered for their founding of the Queen's hospital (186o) and the inauguration (1862) of the Episcopal Church, which, especially since annexation, has prospered. The American Board, which had sponsored the missionaries, deeming Hawaii qualified to graduate (the first nation to do so) from the field of Christian missions, withdrew in 1863 and transferred its work to the Hawaiian Board. Kamehameha V., after calling and dis missing a Constitutional Convention, himself promulgated a new Constitution (1864), which changed that of 1852 less than had been feared.

With his death ended the beneficent Kamehameha dynasty, and after the brief reign (1873-74) of the liberal, popular, pro American Lunalilo, elected against Kalakaua, came the decidedly reactionary reign (18 7 4-91) of the latter, elected as pro-American against Queen Emma as pro-British. The principal forces for good, the chiefs and missionaries, had largely died off. At first Kalakaua ruled fairly well and was largely instrumental in bring ing about the Reciprocity treaty with the United States (1876), which produced far-reaching results. Efforts had been made from time to time since 1848 to effect such a treaty, partly for the economic benefits and partly as an alternative to annexation. The treaty was terminable after seven years on one year's notice, and agitation having arisen in the United States for such termination, an extension for seven years and until one year's notice was ob tained in 1887 but only by giving the United States the exclusive right to enter Pearl harbour and maintain a naval coaling and repair station there—a right which was not exercised.

Reaction and Annexation.—There was ever-increasing en deavour by the king to restore the ancient order with its heathen customs and ideas of absolutism and Divine right, accompanied by extravagance, corruption, personal interference in politics and fomentation of race feeling, until the second generation of mis sionaries and their associates, including many patriotic Hawaiians, finding it impossible to stem the tide by ordinary means, rose in peaceful revolution, but with ample force in the background, and compelled the king to promulgate (1887) a new Constitution providing for responsible ministerial government and other guar antees. The struggle continued, however, not only until the end of that reign (1891), during which there was an armed insurrec tion (1889) by the reactionaries, but even more hotly during the following reign of the king's sister, Liliuokalani. She had some superior qualities as a poet and musical composer and was inter ested in welfare work; however, it was deemed necessary to de pose her (Jan. 17, 1893) and set up a Provisional Government. Annexation to the United States was to be sought.

This failed for the time being and a republic, with probably the most advanced Constitution ever adopted, was established, July 4, 1894. It continued, disturbed only by an unsuccessful in surrection in 1895, until annexation was accepted by Joint Reso lution of Congress in 1898. There has since been general pros perity and progress on the islands, although of late years serious friction has developed between the natives and military and naval men stationed there. The Massie incident in 1931 and the case of two army aviators set upon and beaten in 1933 were symptoms of a bad situation. In the hope of strengthening the local govern ment against such disorders, President Roosevelt asked authority to appoint a governor without regard to his previous residence, but the senate failed to approve the suggestion. The Territory remained Republican in 1936.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-R.

S. Kuykendall and H. E. Gregory, A History Bibliography.-R. S. Kuykendall and H. E. Gregory, A History of Hawaii (New York, 1926) ; W. D. Alexander, A Brief History of the Hawaiian People (New York, 1899), and History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy (Honolulu, 1896) ; W. F. Blackman, The Making of Hawaii, a Study in Social Evolution (New York, 1899, with bibl.) ; L. A. Thurston, Memoirs of the Hawaiian Revolution (1936) ; A. Fornander, Account of the Polynesian Race and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the Times of Kamehameha I. (Lon don, 1878-85) ; W. Ellis, Polynesian Researches, vol. iv. (London, 18S3) ; S. Dibble, A History of the Sandwich Islands (reprint, Hono lulu, 1909) ; U.S. Library of Congress, The Hawaiian Islands: A Bibli ographical List (Washington, 1931) ; J. J. Jarvis, History of the Sandwich Islands (3rd ed., Honolulu, 1847) ; W. R. Castle, Jr. Hawaii Past and Present (New York, 1926) ; D. L. Crawford, Paradox in Ha waii (Boston, 1933) ; The Centennial Book 182o-192o (16 authors, Honolulu, 192o) ; H. B. Restarick, Hawaii from the Viewpoint of a Bishop (Honolulu, 1924) ; R. Yzendoorn, History of the Catholic Mis sion (Honolulu, 1927) ; E. S. C. Handy, Polynesian Religion (Honolulu, 1927) ; L. B. Armstrong, Facts and Figures of Hawaii (19331 with bibl. ; J. D. Dana, Characteristics of Volcanoes with Contribution of Facts and Principles from the Hawaiian Islands (New York, 1891) ; C. H. Hitchcock, Hawaii and its Volcanoes (Honolulu, 1909) ; W. T. Brigham, Kilauea and Mauna Loa Hawaiian Volcanoes (Honolulu, 1909) ; W. L. Green, Vestiges of the Molten Globe, part 2 (Honolulu, 1887) ; C. E. Dutton, Hawaiian Volcanoes, in Fourth Annual Report of U.S. Geological Survey (Washington, 1884) ; W. Hildebrand, Flora of the Hawaiian Islands (London, 1888) ; J. F. C. Rock, The Indi genous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands (Honolulu, 1913), and The Orna mental Trees of Hawaii (Honolulu, 1917) ; G. P. Wilder, Fruits of the Hawaiian Islands (Honolulu, 1911) ; Fauna Hawaiiensis (many authors, Cambridge, 1899-1913) ; D. S. Jordan and B. W. Evermann, The Aquatic Resources of the Hawaiian Islands (Washington, 1903) ; H. W. Henshaw, Birds of the Hawaiian Islands (Washington, 1902) ; C. W. Baldwin, Geography of the Hawaiian Islands (Honolulu, 1908) The Hawaiian Islands and the Islands, Rocks and Shoals to the West ward (Navy Hydrographic Office, Washington, 1903) ; A Survey of Education in Hawaii, made under U.S. Com'r of Educ. (Washington, 192o) ; N. B. Emerson, Unwritten Literature of Hawaii (Washington, 1909) ; H. H. Roberts, Ancient Hawaiian Music (Honolulu, 1926) ; S. D. Porteus and M. E. Babcock, Temperament and Race (Boston, 1926), a study of races in Hawaii; L. Andrews, A Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language, revised by H. Parker (Honolulu, 1922), with place names ; W. D. Alexander, Hawaiian Grammar (5th ed., Honolulu, 1924) ; publications of Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Museum of Poly nesian Ethnology and Natural History (Honolulu) ; Papers of the Hawaiian Historical Society (Honolulu) ; T. G. Thrum, The Hawaiian Annual (Honolulu), vol. for 1924 containing list of articles in first 5o vols.; Annual Reports of the governor (Washington) ; H. M. Ballou, Preliminary Catalogue of Hawaiiana (Honolulu, 1915) .(W. F. Fa.)