Hayti Haiti Haiti

HAITI (HAITI, HAYTI, SAN DOMINGO, SANTO DOMINGO or HISPANIOLA), an island of the Greater Antilles. (See WEST INDIES.) It is separated from Cuba by the Windward passage ; the Mona passage separates it from Porto Rico; to the north is the Atlantic ocean, south, the Caribbean sea. Haiti is wholly in the tropics i 7° 39' and 2o° N. and 68° 20' and 74° 3o' W., area 28,242 square miles. High mountains descend abruptly to the sea along much of the shore. About two-thirds of Haiti is rugged mountain, with small alluvial plains, extensive plateaux and great valleys on the remainder. The western third is the Republic of Haiti, with a negro pop. of about 2,55o,000 speaking a French patois. The rest of the island is Santo Domingo (q.v.), officially known as the Dominican Republic. The boundary, which is disputed, runs north-south at right angles to the major surface features. _ Geology and Physiography.—Haiti has its major geographic features in arcs. These extend north-west-south-east and deter mine the major mountain ranges. The great mountain ranges are anticlinal arches ; between them lie deep synclinal troughs, forming river valleys and interior plateaux and sometimes outlining the coastal alluvial plains. Normal faulting made the broad Trois Rivieres structural valley and many minor land forms.

A complex group of schists, serpentines, extrusive and intrusive igneous rocks, tuffs and altered limestones, shales and conglom erates form the basal complex and are exposed along the axis of the Cordillera Central and the Haitien Massif du Nord. These are primarily Cretaceous. Most of the Samana peninsula and sepa rated areas in the south-western peninsula also have Cretaceous surface rock. Probable Palaeozoic rock is in the schistose lime stones of Tortuga island, the south slopes of the Samana peninsula, certain highly metamorphosed rocks of the Cordillera Central and the float of the Leogane and North plains. The most widespread surface rocks are Eocene limestones, principally in the western third of Haiti. Late Tertiary and Quaternary sediments are com mon. Sedimentary rocks, largely limestones, ranging from prob able Palaeozoic to recent, are about two-thirds of the surface rock. Solution in the more massive limestones made characteristic land and drainage features. There are many recent complex coastal delta plains.

The tectonic event most affecting present surface features was folding and faulting at the end of Miocene and in Pliocene times, when the Cul de Sac-Enriquillo, Artibonite, San Juan and Cibao valleys and the Central plain depression and chief mountain ranges were formed or modified. Folding and mountain-making processes are evidenced by recent earthquakes, chiefly in the densely popu lated unconsolidated alluvial plains of the north-west peninsula.

The Cordillera Septentrional (Monti Cristil runs parallel to the north coast of the Dominican Republic from near Monti Cristi to the Yuna. The western part is low, dry and sparsely populated. North of Santiago, are elevations of probably over 4,00o feet.

Here there is rainfall and production. The low mountains of the Samana peninsula are separated from the Cordillera Septentrional by a low, narrow, swampy plain. Much coffee grows on the south slopes of the peninsula, with large forests on crests and north slopes. South and parallel to these mountains is the Cibao valley, which is continuous with the North plain. In the eastern half of the valley, drained by the Yuna and tributaries, cacao, bananas and tobacco are grown and verdant savannas support many cattle. Here are Santiago and other large towns and the Santiago-Samana railroad. The western part is arid, covered with cactus and mesquite. The Rio Yaqui del Norte traverses it and affords almost the only water for domestic use. The population is sparse, except on the Yaqui delta, where sugar-cane is grown by irrigation. The North plain borders the Atlantic. Near the frontier it is dry and largely covered with long grass savanna. Westward, near Cap Haitien, there is abundant rain and much sugar-cane is grown. To the south, the Cordillera Central and Massif du Nord form the backbone of the island. This is composed of many ranges and isolated mountains. Metamorphic, igneous and sedimentary rocks are exposed. The north and east slopes are humid, with verdant forests. Some mahogany and other commercial woods are ex ploited. Coffee, cacao and native gardens claim much land. Crests of limestone or porous basalt support short-leaf yellow pines and tall grass. The lower lee slopes are dry and unproductive. Through out the Montagnes du Nord coffee grows virtually wild. West of the Trois Rivieres the Montagnes du Nordouest form a genetic continuation and reach nearly to the Mole St. Nicolas. Loma Tina, I0,300 ft. (South central Cordillera Central), is the highest ele vation in the West Indies.

Near the Ennery-Gonaives road the Mornes des Cahos swing south-eastward to the Dominican frontier near Las Cahabas. This range is less high and complex than that to the north ; limestone is the chief surface rock. There is much coffee west of the Artibonite river. To the east the range narrows and the low crest is rolling upland. Between the Mornes des Cahos and the Massif du Nord is the I,000 ft. inter-montaine Central plain plateau. The north western two-thirds is a tall grass savanna. It was once an impor tant cattle area but political conditions have ruined that industry. South-east of Hinche, the chief town, the plateau is intricately dissected and the well-watered river valleys support dense agricul tural populations.

The Central plain merges into the fertile and well-watered San Juan valley at the frontier. South of the Morne des Cahos is the Artibonite valley. At its west or sea end is the Gulf of Gonaive and a great delta plain. This, although but partly developed, con tains about I00,00o ac. (pop. about 200,000) and offers attractive irrigation possibilities. Rainfall, which is but 20.6 in. at Gonaives, increases eastward to 90 in. about Mirebalais. The Artibonite fluctuates greatly with very large floods. It is navigated by rafts and canoes to Mirebalais and large quantities of logwood reach the sea by it. South of the Artibonite, the Chaine des Mateaux (Sierra de Neiba, east of the frontier) swings south-eastward from near St. Marc to Ocoa bay. St. Marc coffee comes from the western section, while in the central part is much short-leaf yellow pine. Next southward is the Cul de Sac-Hoya Enriquillo. This remarkable trough is filled with alluvium and contains the two great lakes, known as Etang Saumatre (c. 69.5 sq.m.) and Lago Enriquillo. Neither has outlets and their waters are salter than sea water. The Lago Enriquillo is drying up; its surface is 145 ft. below sea-level. The Cul de Sac is the most densely populated and productive part of the Republic of Haiti.

Much sugar is produced on irrigated land. The capital, Port au-Prince, is on this plain and owes much of its importance to it. The Dominican portion is not so densely populated or productive, owing largely to aridity. South of the Cordillera Central are two plains, Azua and Seibo, separated by a branch of the Cordillera Central. The western or Azua plain is dry and sparsely populated, but the Seibo has water and a large sugar industry. The mountain range which forms the south-western peninsula continues as the Sierra de Bahoruco, the western part is the Massif de la Hotte (Mont la Hotte, 6, 56o ft.). Here coffee is an important crop and, south of Jeremie, cacao. Inland are virgin forests of mahogany and other commercial trees. The fertile and well-watered plain Aux Cayes is south of the mountains. The central portion of the range is the Massif de la Selle (Mont la Selle, 9,186 ft.). Coffee is important and there is much pine and lignum vitae.

Cliffed coast-lines are the usual types. Where intermittent emergence has taken place there are stair-like sea terraces; at least 20 are on the south shore of the north-west peninsula. Else where the sea has cut cliffs into the mountains, or the cliffs are broken by crescent-shaped sand beaches or deep indentures. The best harbours are on this latter type of coast ; but hinterlands are generally poor. The most important ports are near the popula tion and production centres on the alluvial plains. Here shallows continue some distance from shore and there are many reefs and mangrove barriers.

Climate.

There is a wide climatic range due to diversity of rainfall and the north-east trades. Mole St. Nicholas is in the lee of mountains and has an average annual rainfall of but 19.25 in., while Mirebalais, at the juncture of mountain valleys, has 90.7 inches. No point has much over Too in. and large areas are sterile without irrigation. Temperatures vary chiefly with eleva tion. There are everywhere well-defined spring and autumn rainy seasons, and planting conforms to these. Otherwise, rain varies much with place and year. Port-au-Prince (alt. 121 ft.) and Furcy (5,o5o ft.) have mean annual temperatures, respectively, of 80.96° and 66.0° F. There is a fall in temperature of I° F to every 275 ft. elevation. Thus, even at the highest elevations, temperatures are too high for frost, snow or ice. Daily temper ature range averages about 18° F everywhere, while the monthly range is about 9° F. The heat is not uncomfortable except on sheltered lowlands. Hurricanes are sometimes destructive but are less frequent than in the south-eastern islands.

Fauna and Flora.

There is great wealth of species and numbers among insects, while larger animal groups are lacking in both respects. The most prevalent and harmful insects are mos quitoes. Cockroaches and ants are destructive. Sand flies and chigres abound in some areas. Ticks and blow-flies are a detri ment to stock-raising. Scorpions, centipedes and some large spiders are poisonous, but their bites are not usually fatal. But terflies are surprisingly numerous in late summer. There are few snakes, and none of them poisonous. A number of water-fowl, such as wild ducks, geese and pelicans, occur. Among the shore birds are snipe, flamingos and egrets. Doves and pigeons, a kind of partridge and feral guinea fowl are the chief game birds, and there are white owls, large hawks, woodpeckers and kingfishers. Many fishes, oysters, lobsters and crabs are eaten.Mesophytic vegetation is largely confined to rainy slopes and stream banks. It includes royal palms, silk cotton trees, Haitian oaks, logwood or Campeche, flamboyant, West Indian cedars, short leaf yellow pines, calabash, mahogany, gri-gri, lignum vitae, satinwood, rosewood, Brazil wood, fustic and sassafras. There are also avocados, sour and sweet sops, custard and star apples and zapote. Oranges, limes, grapefruit, guava, mulberry, mango and breadfruit, although exotic, grow wild, as do coffee, cacao and coco-nut trees. Guinea grass grows in cleared forests. Bamboo, tree ferns and begonias are usually found in moist slope forests. Xerophytic types are on lower leeward slopes and dry plains. Tall and short grass savannas occupy wide areas. Cactus is wide spread ; several very high species grow on dry plains. Smaller varieties are Opuntias picardae, caribea and tuna. Lotia candela bra, Cerus heystrek and various agaves and palmettos occur. The bayahonde (Prosophis juliflora), cacti and acacia (Acacia lutea) form thorn forests on drier plains. Among halophytic types the black, red and grey mangroves are frequent on the shores. Cacti and dwarfed thorn trees are on high alkaline coastal soils. The forests were largely depleted in colonial times and after; com mercial stands are mostly limited. Logwood and lignum vitae are for export.

Cotton, maize, tobacco, cocoa, manioc, malanga, banana, plan tain, pineapple and yams are indigenous. Sugar-cane, coffee, rice, guinea grass, citrus fruits, fig, breadfruit and others are acclimated.

The Republic.

This occupies the western third (1 o, 200 sq.m. including Gonaive, Tortuga and the Cayemites; pop. c. 2.550,000.The density of population in parts of the well watered plains is over 500 to the square mile; large sections elsewhere are virtually unoccupied. At least 90% of the population is pure negro and the remainder mulatto. Port-au-Prince is the capital (pop. 125,000). Cap Haitien, on the north coast, was the capital of the French colony and is now the second city (pop. 25,000). Others are Les Cayes (15,000), Gonaives (1 2,000), St. Marc (i0,000), Jac mel (i0,000), Jeremie (8,00o), and Port de Paix (5,000). Although small and backward, Haiti was the earliest State gov erned constitutionally by negroes.

History.

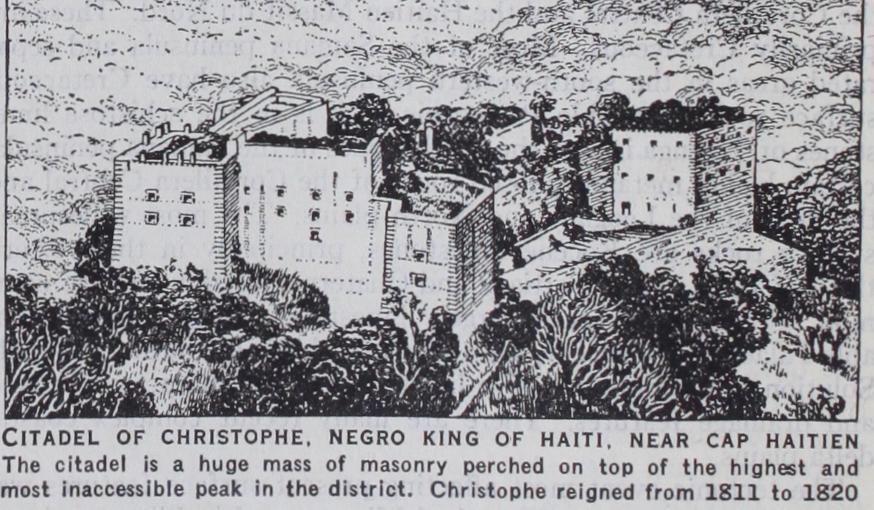

Haiti was discovered by Columbus, who landed at Mole St. Nicolas on Dec. 6, 1492. The inhabitants—Indians (1,000,00o to 3,000,000)—were an agricultural and fishing people who were then suffering from Carib raids. Columbus called the island La Espanola (soon corrupted into Hispaniola) and settlers stayed at La Navidad (Petite Anse), near Cap Haitien. Almost all the Indians were shortly slaughtered or worked to death in quest of gold. By 1512 negro slaves were imported. Sugar-cane was introduced in 1506. The Spanish soon went to the mainland, leaving Haiti deserted. About 1630 French and English buc caneers settled on Tortuga. They soon came to the mainland and (Treaty of Ryswick, 1697) the part they occupied was ceded to France. The French colony of Saint Dominique, based upon slavery and irrigation, was one of the most prosperous of all tropical enterprises. Sugar, cotton, coffee and indigo were staples. Many free mulattos became property owners. Political rights were granted them in 1789. The whites protested and fierce struggles ensued. Then England, solicited by the French planters, intervened, as did the Spanish. Toussaint L'Ouverture, the most notable Haitian soldier and statesman, sided with France and drove out both alien groups, becoming governor for France ; but Napoleon I. soon substituted Gen. Leclerc. A long struggle en sued in which the negroes, aided by fever and heat, successfully competed with the French. Finally, Toussaint was captured by ruse and died in prison in France. Jean Jacques Dessalines be came leader and defeated Richambeau, Leclerc's successor, in Nov. 18o3.On Jan. 1, 1804, independence was declared and the Indian name Haiti taken for the State. Dessalines, made governor for life, began by massacring all whites. He soon crowned himself emperor, but in 1806 was assassinated because of his tyranny. Henri Christophe then ruled in the north as King Henry I., and built the famous citadel La Ferriere which stands south of Cap Haitien. Alexandre Sabes Petion, a most able mulatto, ruled the south. War raged until Gen. Jean Pierre Boyer got control of the south (1818) and until the death of Christophe (1820). In 1821, the Spanish portion of the island proclaimed its independence. Boyer invaded it and in 1822 ruled the whole island. A revolu tion drove him out in 1843 ; Santo Domingo (q.v.) was founded and there have since been two nations on Haiti.

There was almost constant revolution until American inter vention (1915). Irrigation projects fell into decay; production and foreign trade dwindled. Political mismanagement increased the public debt. The courts were corrupt. Education, except that carried on by French priests, practically ceased. There was little protection of property and no industrial encouragement.

Poverty and disease added to the general distress. The interior swarmed with bandits. In Dec. 1913, Oreste Zamor and Davilmar Theodore overthrew Michel Creste; Zamor became president on Feb. 8, 1914 and was displaced by Theodore on Nov. 7, 1914. Intervention by the United States.—Vilbrun Guillaume Sam assumed government on March 4, 1915, holding it against violent opposition until forced to seek refuge at the French lega tion on July 26, 1915. About 200 political prisoners were bayo neted in the gaol at Port-au-Prince and Sam was dragged from the massacred by the mob. Two hours later U.S. marines landed at Port-au-Prince, assumed occupation, disarmed the na tives and restored order. U.S. naval officers took over most administrative functions but the Haitian Government remained. On Aug. 12, 1915, Sudre Dartiguenave was chosen president by the Haitian Congress. On Feb. 28, 1916, the U.S. Senate unanimously gave its advice and consent to a treaty (Nov. II, 1916) with Haiti. It was made for ten years and provided that "the Govern ment of the United States will, by its good offices, aid the Haitian Government in the proper and efficient development of its agri cultural, mineral and commercial resources and in the establish ment of the finances of Haiti on a firm and solid basis," and stated how. A serious outbreak against American authority took place in July 1918, under the leadership of Charlemagne Perlate, an ex-bandit. The gendarmerie being inadequate, the marines were compelled to act. In May 192o peace was restored and five years later the original treaty was extended for ten years.

Under Brig.-gen. John H. Russell, high commissioner, were five departments : financial adviser-general receiver of customs, pub lic works, sanitary service, agricultural service, and gendarmerie. These reduced the public debt (about $31,000,00o in 1915) to less than $20,000,Ooo in 1927. Tax and customs laws were revised and favourably affected foreign trade. Bridges, trails, harbours, pub lic buildings, irrigation and telephone, telegraph and lighthouse services, and sanitation were improved. Agricultural informa tion was spread and such crops as sisal introduced. No general educational reform had been authorized, and but two schools'were maintained besides those of the native government, which were very poor. Some of the small upper class are educated in France, but social stratification prohibits the dissemination of culture.

Resentment against foreign rule continued on the island and led to renewed outbreaks in 193o. President Hoover, therefore, ap pointed an investigating committee, headed by W. C. Forbes, upon the basis of whose recommendations a new treaty was drafted in 193 2. By the terms of this instrument, military and civil authority were gradually to be withdrawn, but fiscal supervision was to remain. The Haitian national assembly re jected this as insufficient.

After the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt a second offer was made, similar to that of 193 2 but promising earlier military evacuation. This was signed in the form of an executive agree ment, August 7, 1933, and the last detachment of marines de parted from the republic a year later. The partial victory, however, contented neither Haiti nor the foes of dollar diplomacy in the United States. And as President Roosevelt expanded his good neighbour policy, he reopened negotiations in April with the result that an understanding was reached whereby fiscal autonomy might also be soon reestablished.

Production and Trade.—Most production is through small farmers and is consumed locally. Exports, excepting sugar, are wild or semi-wild products gathered by peasants in off seasons. Coffee is the most important export (almost 75% of the total), and thus Haiti has the disadvantages of a one-crop country; national and coffee trade prosperity are almost one. The average values of the chief exports for 1916-17 to 1926-27 were: coffee, $10,801,933 ; cotton, $1,477,245; logwood, $813,564; sugar, $45o, 002; cacao, $391,192. All exports amounted to $14,916,413. Hides and skins, cotton-seeds, honey and bees-wax, lignum vitae and turtle shells are exported and follow cacao in the order named. France, in this period, used 48.99% of the exports, largely coffee, and the United States 29.4%, including logwood, sugar and cotton. Imports (average for above period, somewhat exceed exports. This is partly offset by money brought by labourers from Cuba and by American marines. Food-stuffs, especially wheat flour, are 37% of the imports; textiles, largely cotton cloth, 28%. Others are building materials, mineral oils, soap and liquors. Tobacco importation has recently been replaced by local pro duction. The United States sends 82% of imports, Great Britain 6%, and France 5%. Port-au-Prince handles 2 I % of exports and 54% of imports. Cap Haitien, Jacmel, Les Cayes, Petit Goave, Gonaives and St. Marc each handle 5 %–I o % of the foreign trade. The total national revenue, 1926-27, was $7,772,306 (72% from customs). The coffee export tax ranks first, but its importance has recently declined due to a better balanced schedule. Transpor tation is inadequate for bringing products to port. However, nearly i,000 m. of road, open for motors at least part of the year, have been opened. These are bound by an intricate net work of trails to the remotest districts. There are only 65 m. of national railroad. This unit connects Port-au-Prince and St. Marc. The Gonaives-Ennery division equipment is being partly trans ferred to the St. Marc–Petite Riviere, now under construction. The Haitian-American Sugar Company also uses some 55 m. of track (Cul de Sac and Leogane plains). Its gauge is not that of the national line. The National Bank of Haiti, a subsidiary of the National City Bank of New York, and the Royal Bank of Canada, conduct banking.