Hearing

HEARING. The air around us is constantly disturbed by vibrations, which travel through it in the form of waves (see SOUND) . Similar wave movements are transmitted by water, and by most of the solid bodies by which we are surrounded. All animals higher in the scale of evolution than the amphibia, and many of those more primitive, have developed organs by which they are able to perceive these vibrations, and their relation to their environments is thereby greatly extended. The higher animals can signal to one another by means of the sounds which they themselves produce, and their hearing mechanism is able to interpret the purport of such signals. Articulate speech and music are the highest development of this system of sound signals, and their interpretation necessitates a refined power of analysing sounds by the organ of hearing, with which is associated a corre sponding development of the mental faculties. The word HEAR ING is used to denote both the process by which vibrations of sounds act upon the sense organs, and the particular sensation aroused in consciousness by such stimulation.

Range of Hearing.

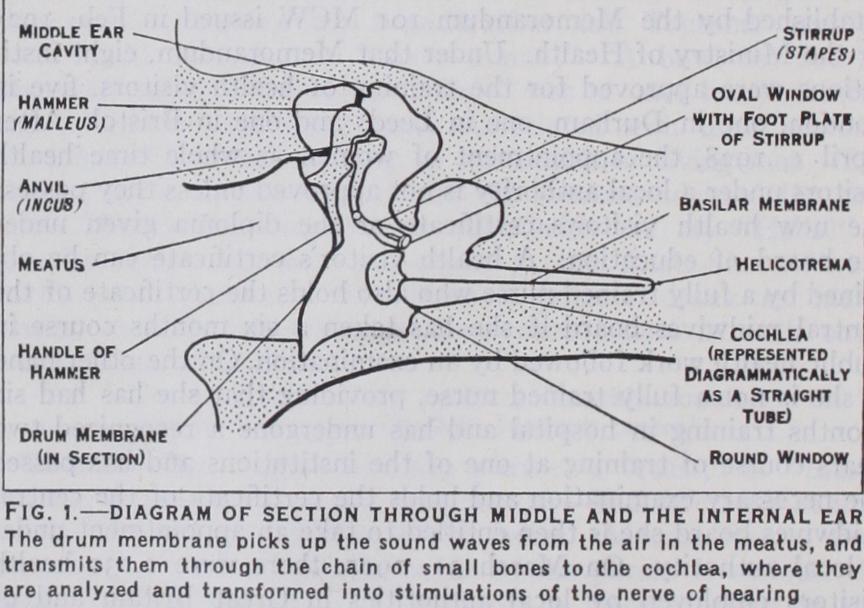

Only those vibrations which recur within certain limits of frequency give a sensation of sound. These limits vary in different individuals. From 20 vibrations to 20,000 per second may be taken as the average range. Many animals hear sounds of much higher pitch than man is able to. On the other hand, fishes and many marine animals appear to be sensitive to relatively slow vibrations, but not to those more rapid.The ear consists of three parts named the outer, middle and inner ear respectively. The outer ear collects sound waves, the middle ear transmits them to the inner ear which analyses them and converts them into nerve impulses, as which they are con ducted to the brain, where they are received and interpreted. A description of the EAR is given under that heading. This section deals with its working, and with the adaptation of the structure of its various parts to the performance of their several functions.

The External Ea.

This is divided into the auricle, or flap of the ear, and the meatus. The human auricle acts, to a certain extent, as a collector of sound waves, but it is far inferior in this respect to the auricles of many animals, notably the horse and the ass. Sound waves are gathered up by the hollow recess, the concha, and projected forward on to the back of the tragus, by which they are directed into the skin-lined passage, the auditory meatus, which leads to the drum of the ear. The auricle loses some of its collecting power if the hollows of the concha and tragus are filled with wax. The form of the human auricle is adapted to collect sounds coming from the front. This is an advantage to man in communicating with his fellows, enabling him to concentrate both sight and hearing on the source of sound. Sounds are then conducted to both ears equally, and the one ear reinforces the other. When one ear is defective sounds are best heard by turning the better hearing ear to the source of sound. The advantage of correlating sight and hearing is then lost. Con sequently, the deaf subject, when listening to conversation, places his open hand behind the auricle, and projects it forward, so as to increase its efficiency as a collector of sound coming from the front, whilst at the same time he is able to supplement his hearing by watching the motion of the lips of the speaker. The power of hearing sounds coming from one side is only slightly lessened when the auricle on that side has been lost as the result of injury. It would appear that the auricle, in spite of its beautiful modelling and delicate curves, is more ornamental than useful. Man possesses but little power of moving his ears, the muscles serving that function being rudimentary. Many animals can both rotate their ears, and expand them, thereby increasing their utility as sound collectors, and helping them to locate the direction of the sounds.The length of the auditory meatus is a little over 1 inch. The passage is irregular in width and curvature. This minimises reso nance effects, but does not entirely obviate them. The intrinsic tone of the meatus varies in different individuals according to its size and shape, but is usually within the limits to Sounds of the same pitch are heard reinforced. Helmholtz attributed the peculiarly penetrating quality of the note of the cricket to its pitch falling within this range.

The Middle Ear or Tympanum.

Waves of sound in air are of great length in comparison with the dimensions of the ear itself. They range from fin. to 55f t. The function of the con ducting mechanism of the middle ear is to convert the alternating compressions and rarefactions of the air in the meatus caused by sound waves into mechanical pushes and pulls of much smaller range, but greatly increased force, on the footplate of the stapes, by which they are transmitted to the inner ear. The air waves in the meatus impinge on the drum membrane, which separates the outer from the middle ear. This is an extremely light and delicate structure. Its inertia is, consequently, very small, and it readily picks up the waves of sound without any perceptible lag, and its movements cease just as promptly when the sound ceases. Its vibrations are "dead beat." It is shaped in a subtle curve, slightly bulging in the lower half and indrawn in the upper half. Its centre, where it is attached to the tip of the malleus, is retracted. Consequently, the fibres of which it is composed are not tense in any direction, and it has no inherent period of vibra tion to cause "distortion" of the sound waves. The movements of the drum membrane are communicated to a chain of small bones, the auditory ossicles. In birds and amphibia there is only one ossicle—the columella—a straight rod connecting the centre of the membrane to the oval window. In mammals the ossicles are three in number, the malleus or hammer, the incus or anvil, and the stapes or stirrup. The "handle" of the hammer is firmly incorporated with the upper half of the drum membrane. The anvil consists of a body having a slightly concave surf ace, and two processes, one long and one short. The surface in the body of the anvil is jointed on to the head of the hammer, so that the two together form a curved lever. The long process lies nearly parallel to the handle of the hammer, but is somewhat shorter. The short process of the anvil fits into a depression in the wall of the middle ear cavity above the level of the drum membrane. Both bones are suspended in position by fibrous bands strung across the cavity at this level, and these supports form the axis of the lever, round which it rotates. The long process is con nected by a ball-and-socket joint to the head of the stirrup. The name of this ossicle exactly expresses its shape. The footplate of the stirrup fits into an oval opening in the wall of the inner ear, named the oval window, to the margins of which it is connected by a fibrous membrane, but not sufficiently firmly to prevent a certain freedom of movement. The axis of the stirrup lies approxi mately parallel to the plane of movement of the curved lever formed by the hammer and anvil. The ratio of length of the short arm of the lever (i.e., the long process of the anvil) to the long arm (i.e., the handle of the hammer) is as 2:3. The ampli tude of movement communicated by the lever to the stirrup is therefore only that of the tip of the handle of the hammer, but the force is increased in the proportion of 3 :2. The movements of the stirrup within the nitch of the oval window are not those of a simple piston, but rather those of a trap door. Albert Gray has shown that the footplate moves as though pivoted on an axis transverse to its greatest length, at the junction of its posterior third and anterior two-thirds. Its maximum movement is, there f ore, at its extreme anterior edge.

As the area of the drum membrane greatly exceeds that of the oval window, the pressure transmitted by the ossicles is concen trated. This fact, and the mechanical advantage at which the lever works, increases the force of the impulses transmitted from the drum membrane to the inner ear about ninety times.

The tension of the chain of ossicles is controlled by two small muscles, the tensor tympani which pulls the handle of the hammer inwards towards the inner ear, and the stapedius which pulls on one of the arms of the stirrup, so as to withdraw the footplate from the nitch of the oval window. The two muscles thus antago nise one another, and their combined action is to keep all the bones pressed closely into contact and to prevent any play in the joints by which they are connected. It is probable that this tightening up of the ossicular lever is part of the act of attention which distinguishes listening from casual hearing. The joint between the hammer and the anvil which connects the two arms of the lever is shaped so that it transmits directly pushes from the hammer to the anvil, but allows a certain amount of sliding movement when the hammer is pulled outwards. The advan tage of this mechanism is probably as providing a safeguard against injury to the delicate structures of the inner ear in case of sudden distension of the middle ear cavity with air under pressure as may occur, for instance, in violent blowing of the nose. This forces the membrane and the hammer outwards, and would cause a violent drag on the footplate of the stirrup tend ing to wrench it out of the oval window, were it not for the forward slip of the hammer on the anvil, which breaks the force of the pull.

The middle ear cavity is filled with air. It has a ventilating shaft, the Eustachian tube, which communicates with the pharynx. In most people this tube is closed during rest, but opens with every swallowing movement, so that the air is frequently renewed, and its pressure is kept in equilibrium With that of the outer air.

Unless this equilibrium is maintained the drum membrane is sucked inwards and rendered tense. This diminishes the acute ness of hearing, and causes a feeling of pressure in the ears. These symptoms are relieved by swallowing. This is a matter of common experience to aviators and miners when rapidly ascending to levels of lower, or descending to levels of higher atmospheric pressure. Partial or absolute blockage of the Eustachian tube is one of the commonest causes of deafness.

The Inner Ear or Labyrinth.

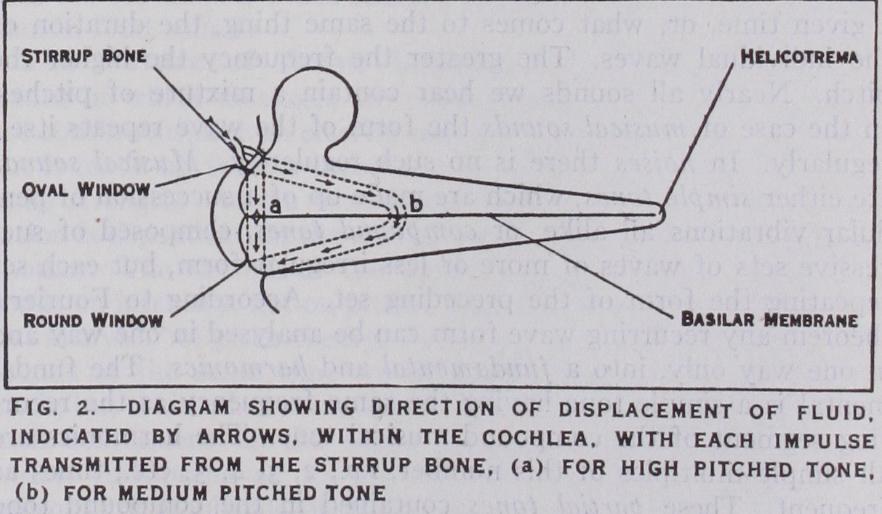

This consists of a compli cated series of cavities and canals enclosed by hard bone, and filled with clear fluid. Within these are suspended a second series of sacs and tubes with extremely delicate membranous walls which are also filled with fluid, and are richly supplied with nerves. They contain the sense organs. There is no direct communica tion between the two concentric systems of cavities. It was formerly thought that the whole organ was concerned with hear ing, but it is now generally recognized that only the anterior cavity, the cochlea, is sensitive to sound. The rest of the organ is concerned with the maintenance of equilibrium in the various pos tures assumed during rest and progression. (See EQUILIBRIUM. ) The form of the cochlea exactly resembles a small snail shell, from which it takes its name. It measures 4 by *in. It con sists of a tube or tunnel coiled spirally two and a half turns, and is surrounded by dense bone. The total length of the tube is rather less than an inch and a half. It diminishes in diameter as the spiral is ascended, and is more closely coiled at its apex than at its base. A minute shelf of bone runs round the inner wall of the coiled tube, from the outer edge of which a fibrous membrane, the basilar membrane, stretches across to the outer wall, to which it is attached by the wedge shaped spiral ligament. The basilar membrane is built up of a large number (some 25,000) of fine transverse fibres, covered over on either side by layers of sof t gelatinous cells. The sensitive elements of the cochlea are dis posed along the upper surface of the membrane. The spiral lamina and basilar membrane thus divide the tube of the cochlea along its whole length into an upper and lower chamber, the par tition being partly bony and partly membranous. A second parti tion, Reissner's membrane, runs obliquely from the spiral lamina to the outer wall of the cochlea, forming with the basilar mem brane a triangular compartment within the upper chamber, to enclose the sense organ. The function of this membrane seems to be to separate the fluid surrounding the sense elements (the endo lymph) from the surrounding fluid (the perilymph). The basilar membrane is not continued quite to the apex of the cochlea, there being a small gap beyond it, the helicotrema, by which the upper and lower chambers communicate. There are two openings in the bony wall separating the middle and inner ear. One, the oval window, is filled by the foot plate of the stapes. It opens into the upper compartment. The other, the round window, communicates with the lower compartment, and is filled by a rather slack mem brane. (Figs. 2 and 3.) A simple diagram (fig. 2) will help to illustrate the mechanics of the inner ear. Suppose the cochlear tube to be rolled out straight, we have then a long tube, enclosed in rigid walls, divided horizontally by a yielding partition, the basilar membrane. At the near end we have the oval window opening into the upper chamber, and the round window into the lower. At the far end is the helicotrema. Sound impulses transmitted from the drum membrane through the chain of ossicles to the stirrup tend to drive the foot plate inwards, and, consequently, to increase the pressure of the fluid within the cochlea. This causes the mem brane of the round window to bulge outwards, as this is the only part of the enclosing walls which is not rigid. The consequent displacement of fluid must take place either through the helico trema, or by bulging the basilar membrane downwards. It is only comparatively slow changes of pressure which cause to and fro movements at the helicotrema. Rapid alternations of pressure, such as those caused by sound waves, are transmitted through the cochlea across the basilar membrane, which is set in vibra tion. The movements of the basilar membrane stimulate the sensitive cells attached to its upper surface, by means of which a sense of hearing is aroused.

The Sensitive Mechanism.--The

actual sense elements are certain elongated epithelial cells, each of which carries a row of fine hairs projecting from its free surface, called hair cells. In birds and amphibia the hair cells are simply packed in transverse rows on the basilar membrane. In mammals the cells are fewer in number, and are placed within the recesses of an elaborate supporting structure of Corti's organ, which lies on the inner half of the membrane. The framework of Corti's organ is com posed of rather stiff fibres, which retain the delicate hair cells in position and protect them from pressure. This supporting frame work also raises the free ends of the cells well above the surface of the basilar membrane, and increases their range of move ment when the latter is vibrating. The sensory hairs project above the flat surface of Corti's organ into the substance of the tectorial membrane, which consists of a mass of soft jelly en meshed in a fine network of fibres, and tethered to the outer end of the spiral lamina. Its purpose is to clog the movements of the hair processes, so that when Corti's organ is vibrating, the hairs are pulled first in one direction and then in another. Each hair cell has a nerve fibre attached to it. The hairs act like trig gers. When pulled upon they release a discharge of energy from the hair cells, which travels as a nerve current through the audi tory nerve to the hearing centre in the brain. According to Retzius there are about 20,000 auditory nerve-fibres connected with Corti's organ.

Analysis of Sound.--We

not only hear sounds but we are able to interpret them. This implies that we distinguish the character istic features of the different sounds which reach us. Sound waves differ in intensity and pitch. Intensity corresponds to the degree of condensation and rarefaction of the air in the successive phases of sound waves. Pitch signifies the number of waves arriving in a given time, or, what comes to the same thing, the duration of the individual waves. The greater the frequency the higher the pitch. Nearly all sounds we hear contain a mixture of pitches. In the case of musical sounds the form of the wave repeats itself regularly. In noises there is no such regularity. Musical sounds are either simple tones, which are made up of a succession of pen dular vibrations all alike, or compound tones, composed of suc cessive sets of waves of more or less irregular form, but each set repeating the form of the preceding set. According to Fourier's theorem any recurring wave form can be analysed in one way and in one way only, into a fundamental and harmonics. The funda mental is a simple tone having the same frequency as the recur ring segment of the compound musical tone. The harmonics are all simple multiples of this number, i.e., 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., times as frequent. These partial tones contained in the compound tone can be picked up separately by resonators. The trained musical ear can also detect them.Noises, in spite of the irregularity of their wave forms, have pitch, or ranges of pitch, but these pitches are not so easy to detect as is the case with musical sounds. They too may be regarded as being composed of a number of different pitches, but the components are usually very numerous, and are not distrib uted in a harmonic series. The constituent pitches can, however, be picked out by resonators.

It follows that the nerve impulses which are sent to the brain from the cochlea must carry with them some criterion by which the pitch of the various constituents of the sounds may be recog nised, and also the relative intensity of those constituents; and, further, if these two factors are determined, all sounds, musical or otherwise, can be distinguished. There is one other important characteristic of sound, and that is the rate at which the various alternations of pitch and intensity follow one another. In music this rate is regular and is called rhythm. In noises it is irregular, but it is none the less an impor tant factor in determining the character of the noise.

Pitch Perception : Histori

cal.—The problem of how we recognise the pitch of sounds, and detect the simple pitches con tained in a compound tone, has for long been a subject of contro versy. It follows from what has been said in the last paragraph that if it could be shown that the ear contains a series of resonators, each tuned to vibrate to notes of one pitch, and extending over the whole of the audible scale, and that if each of these resonators were connected by a nerve fibre to the brain, the problem would be solved in a simple manner. This explanation seems to have occurred independently to a number of the earlier investigators of the ear, amongst whom may be mentioned Cotugno, le Cat, Johannes Muller, Sir Charles Bell and Thomas Young. It was Helmholtz, however, who gave a definite form to the resonance theory, which is usually associated with his name. He based his conception on a generalization :—"The analysis of compound into simple pendular vibrations is an astounding property of the ear. When we turn to external nature for an analogue of such an analysis of periodic motion into simple motion, we find none but the phenomena of sympathetic resonance." Thus Helmholtz approached the study of the internal ear with the hope of recog nizing in it the confirmation of this pronouncement. The anatom ical evidence he was able to bring forward was, however, slight and unconvincing, and the objections were formidable. Not the least of these was the minute size of the cochlea. The fibres of which the basilar membrane is composed do not exceed of an inch at their longest, and yet it was supposed that they could vibrate to tones nearly two octaves below the pianoforte scale. At first enthusiastically received, there was subsequently a reac tion in scientific opinion, and the theory for a long time was discredited. A number of alternative theories were proposed, none of which seems to offer a full explanation of the facts of hearing, while some have since been shown to be untenable. The theory most in favour for a time was the "telephone theory" of Rinne and Voltolini, which sought to evade this difficulty by referring pitch analysis to the brain. It was supposed that the whole basilar membrane vibrated like a telephone disc, and trans mitted to the auditory nerve impulses which followed exactly every variation of frequency and intensity of the sound waves. It is now known that the nerve fibres do not conduct currents like the electric flow in wires, and that separate impulses are not transmitted at a greater rate than about r,000 a second, a fre quency much below that (viz., about 25,00o) of the highest audible tones. So the theory fails.The Resonance Theory of Pitch Perception.--Helmholtz' theory is that different pitches of sound impress themselves on the basilar membrane at different levels, and that, if the sound con tains several pitches, each pitch causes a movement at a different level, and consequently stimulates a different set of nerves. The mechanical principle on which this happens is resonance. (See SOUND.) If a note of simple pitch be sounded near a harp or open piano, the string tuned to the same note is set in vibration, whilst the other strings remain silent. If a compound tone, such as a vowel, is sung to the piano, the particular strings tuned to the various pitches contained in the compound tone each pick up the particular tone to which they are in tune, and a sound is given out by the combined vibration of these strings which can be recognized as the particular vowel sung. Helmholtz compared the transverse fibres composing the basilar membrane to the strings of a piano, and he suggested that each fibre or small group of fibres, was tuned to vibrate to one particular pitch. This con ception was supported by Hensen's observation that the length of the fibres increases as the basilar membrane ascends towards the apex of the cochlea. The pitch of a stretched string depends on its length, its tension, and its mass, according to the formula for vibrating strings : n =I- , when n = number of vibrations per m sec., 1= length in centimetres, t = tension in dynes, and m =mass in grammes of i cm. length of the string. Short, light, tense strings give high pitched tones ; long, relatively loose and heavy strings give low tones.

The Resonating Mechanism of the Cochlea.--If

the fibres of the basilar membrane are tuned to respond to tones ranging over ten octaves, they should show a wide range of variation in the factors, length, tension and mass. If this variation were in length alone, the longest fibres would have to be i,000 times longer than the shortest. If they differed in mass, or in tension alone, the corresponding variations would have to be as i : r,000,000. Meas urements show a difference of a little more than z :3 in the length of the fibres. By itself this is only sufficient to account for a range of less than one and a half octaves. The evidence for variation in tension was supplied by Dr. A. A. Gray of Glasgow in 1900, in his observations on the spiral ligament. This structure attaches the basilar membrane to the outer wall of the cochlea. It is made up of fine fibres, radiating fanwise from the outer end of the basilar fibres. Its most striking feature is a gradual increase in bulk and density from the apical to the basal end of the cochlea. This seems to point clearly to a corresponding increase in tension on the fibres to which it is connected. The tension would be greatest on the shortest fibres and least on the longest fibres, as required by theory. With regard to differentiation by mass, we have to consider not merely the mass of the fibres themselves, but also the load they carry. The load is supplied by the fluid in which they are immersed. Supposing the fibres to be vibrating at any particular level of the cochlea, there must be a corresponding oscillation of the fluid intervening between the vibrating fibres and the round and oval windows (see fig. 2) . The further the level of vibration is from the windows, the greater will be the mass of fluid moving. Consequently, the more distant the fibres, the more heavily are they loaded. Thus the variations in all the three factors, length, tension and mass, are in accordance with the supposition that the fibres are tuned to a progressive range of pitch. This cannot be taken as an absolute proof of the theory, but it adds substance and verisimilitude to what appears at first sight a rather fanciful conception. In particular, the recognition of the part played by the fluid load explains the difficulty arising from the minute scale of the resonators. The fibres, though short, are very heavily weighted. This lowers their pitch. A model devised by Wilkinson embodies the mechanical principles outlined in the preceding paragraph. It represents a basilar membrane and round and oval windows in their relative positions. It is filled with water. Tuning forks applied to the stirrup set the basilar membrane vibrating at levels varying with the pitch of the tuning forks employed. The model illustrated roughly the supposed res onating mechanism of the cochlea.Physiological Evidence in Favour of the Resonance Theory.—Yoshi showed that long continued subjection of guinea pigs to tones of one pitch produced damage to the cochlea at levels varying with the pitch. High pitched tones damaged the basal coil whilst lower pitches affected levels nearer the apex. Ritchie Rodger and Putelli found that in boiler makers' deafness loss of hearing was principally for those tones to which they were con stantly subjected whilst at work. Weinberg and Allen found that fatigue induced by tones of one pitch caused relative deafness for that pitch, but not for other pitches. All these observations tend to show the existence of separate pitch receptors in the ear, and those of Yoshi afford evidence that these receptors form a graduated series at different levels of the cochlea. Though by no means universally accepted, the resonance theory is advancing in favour with physiologists, as it is recognised that it offers a reason able explanation of the main facts of hearing.

One great difficulty with the resonance (or any other) theory of hearing is that it seems impossible that the localisation of the vibration in the basilar membrane can correspond in sharpness and definition with the sense of pitch aroused. Some vibrations of fibres on either side of the maximum point must take place. How then do we hear a sound of single pitch? At present this question cannot be answered. Further research on the subject of the integration of nerve impulses may throw light on it. A. A. Gray has indicated a similar paradox in the sense of touch. When a small area of the skin is pressed upon by a blunt point, we feel the pressure at its point of maximum incidence, not on the whole area. Similarly we refer pitch to the level of maximum vibration of the basilar membrane.

The only serious rival of the resonance theory is Ewald's. From observations made on a model designed to illustrate the move ments of the basilar membrane, he concluded that sound impulses evoke a number of evenly spaced "stationary waves" in the mem brane, and that the number of these waves is different for each pitch. The membrane he used was not differentiated as to length, tension or mass. Consequently his conclusions can only have weight if the evidence for such differentiation in the cochlea is rejected. The application of his conception to the facts of hearing is full of difficulties. The same may be said of the "travelling bulge" theories of Hurst, Meyer and Ter Kuile which at one time met with considerable favour.

Perception of Intensity of Sound.

Sounds must have a cer tain intensity before they can be heard, but the ear is wonderfully sensitive. Rayleigh computed that the minimal energy of sound capable of being perceived by the cochlea is much the same as that of light exciting the retina, and that "the ear is able to recog nise the addition and subtraction of densities far less than those to be found in our highest vacua." The sensitivity is greatest for pitches ranging from 50o to 6,000 vibrations a second. This range comprises the higher partial tones of human speech on which the distinction between the various vowels and consonants depends.Perception of intensity of sound accords with Weber's law, which states that in order to produce a perceptible increase in intensity of a sensation an equal fraction must be added to the previous intensity of the stimulus, whatever its value. This means that the ear detects much smaller differences in loudness in weak than in loud sounds.

The Nature of Nerve Impulses.

The nerve current by means of which messages are conveyed to and from the brain is not continuous, like an electric current flowing in a battery circuit, but is made up from a succession of separate impulses, all of the same strength. Adrian has recently shown that intensity of sen sation is dependent on the rate at which these impulses follow one another. The rhythm of the impulses in the auditory nerve de pends on intensity, not on pitch. This finally disposes of the "cen tral analysis" of pitch theory. When the ear receives a number of sounds at the same time we distinguish not only their relative pitch, but their relative loudness. This fact seems to indicate that each constituent of the sound is separately impressed on the basilar membrane at its appropriate pitch level, and with its appropriate amplitude of vibration.

Location of Sound.

Our judgment of the direction from which sound is reaching us depends mainly on the relative intensity of the sound in the two ears, it being loudest in the ear turned to the source. Location can be assisted by turning the head in differ ent directions. High pitched sounds of short wave length cast a shadow, but low pitched sounds of long wave length bend round the head, and are heard with indistinguishable intensity in the two ears. Consequently pure tones of low pitch are difficult to locate. In the case. of compound tones, the character of the sound in the two ears is altered by the weakening of the higher pitched partials on the side of the sound shadow, and this gives a criterion for judgment of direction. It even makes it possible for familiar sounds to be located by persons deaf in one ear.Beats.—According to the principle of interference (see SOUND) when two notes nearly of the same pitch are sounded together they will alternately augment and diminish each other. This gives rise to "beats." The number of beats per second equals the difference in number of vibrations in the two tones. The beats are heard as rhythmic variations in intensity. When they follow one another rapidly they are accompanied by a disagreeable sensation of roughness, which is at a maximum when the beats are about 32 a second. Helmholtz ascribed this roughness to an overlapping of the area of the basilar membrane set in vibration by each tone separately. The pitch of the two tones is distinguished by the relative position of the maximum points of the disturbance. As these points at either end of the disturbed area are vibrating at different rates the intermediate portion of the membrane will be moving in an irregular "flickering" manner. It is this "flickering" that causes the unpleasant roughness. With greater differences of pitch the maximum points are further apart, and the overlapping is less, or entirely absent.

Combination Tones.

When two tones of different pitch are sounded together moderately loud, both are heard separately, and there may also be heard a deeper tone of a frequency equal to the difference between the frequencies of the other two ; for example, two tuning forks of Boo d.v. and I,o24 d.v. respectively yield a difference tone of 224 d.v. There is also another combina tion tone, the summational tone, whose frequency is the sum of the two tones evoking it. It is much more difficult to hear, and to explain. The numerical relationship of the difference tone to the generating tones is the same as that of beats, and it is usually held that the beats generate this tone when they become sufficiently rapid. However, the roughness of beats and the difference tone can sometimes be heard together, which seems to indicate that they act in a different way on the cochlea. Much controversy has raged on the subject of beats and combination tones, and it is argued that if the ear works on the principle of resonance they ought not to be heard. This would be true if the conducting mech anism of the ear were entirely free from distortion, and if the cochlea were a perfect resonator. It is probable that the ear fulfils neither of these conditions.

Consonance and Dissonance.

Some combinations of tones blend together and appear smooth, others appear to be rough. The smooth or consonance intervals in music correspond to simple numerical relationships between the number of vibrations of their components. All the harmonic partials with frequencies r : 2 (octave), i :3 (twelfth), i :4 (double octave), and so on, are perfectly consonant. Then follow in order of lessening conso nance the intervals 2 :3 (fifth) and 3 :4 (fourth) ; then with increasing dissonance 3:5 (major sixth), 4:5 (major third), 5:8 (minor sixth) and 5:6 (minor third). Helmholtz pointed out that the simpler the numerical relationship between two tones, the more evenly spaced on the scale, in relation to one another, are the two series of harmonic partials accompanying each fundamental tone. Assuming a similar distribution of the vibrat ing levels produced by each of these partial tones on the basilar membrane, there would be least overlapping of the areas occu pied by the several tones when the frequencies of the two primaries had the simple relationship characterizing consonant intervals. Dissonance he attributed to roughness produced by overlapping of the vibrating areas of either the primary tones or their harmonics. This might account for the quality of disso nance, but is an insufficient explanation of consonance, which is more than a mere absence of dissonance. There is a unity, a sense of blending, in consonance which is not a purely negative feature. The octave interval is unique. There is a sense of identity in tones an octave apart. They are felt to be the end of one stage and the beginning of another. Modern music makes free use of dis sonant intervals, but it is built up on a background or framework of simple tonal relationships. Whether this has developed out of the exigencies of tuning in stringed instruments, or is imposed by some inherent graduation of the scale of the basilar membrane on the basis of harmonic intervals, is too speculative a subject to be discussed here.The subject of hearing has always been regarded as one of the most difficult problems of physiology. The cochlea is a small and extremely delicate organ deeply buried within recesses of one of the hardest bones in the body. This greatly increases the diffi culty of investigating its structure and function. Many of the problems connected with hearing are still obscure, and call for further research. (G. Wi. )