Helmet

HELMET, a defensive covering for the head. The present article deals with the helmet during the middle ages down to the close of the period when body armour was worn. For the helmet worn by the Greeks and Romans see ARMS AND ARMOUR.

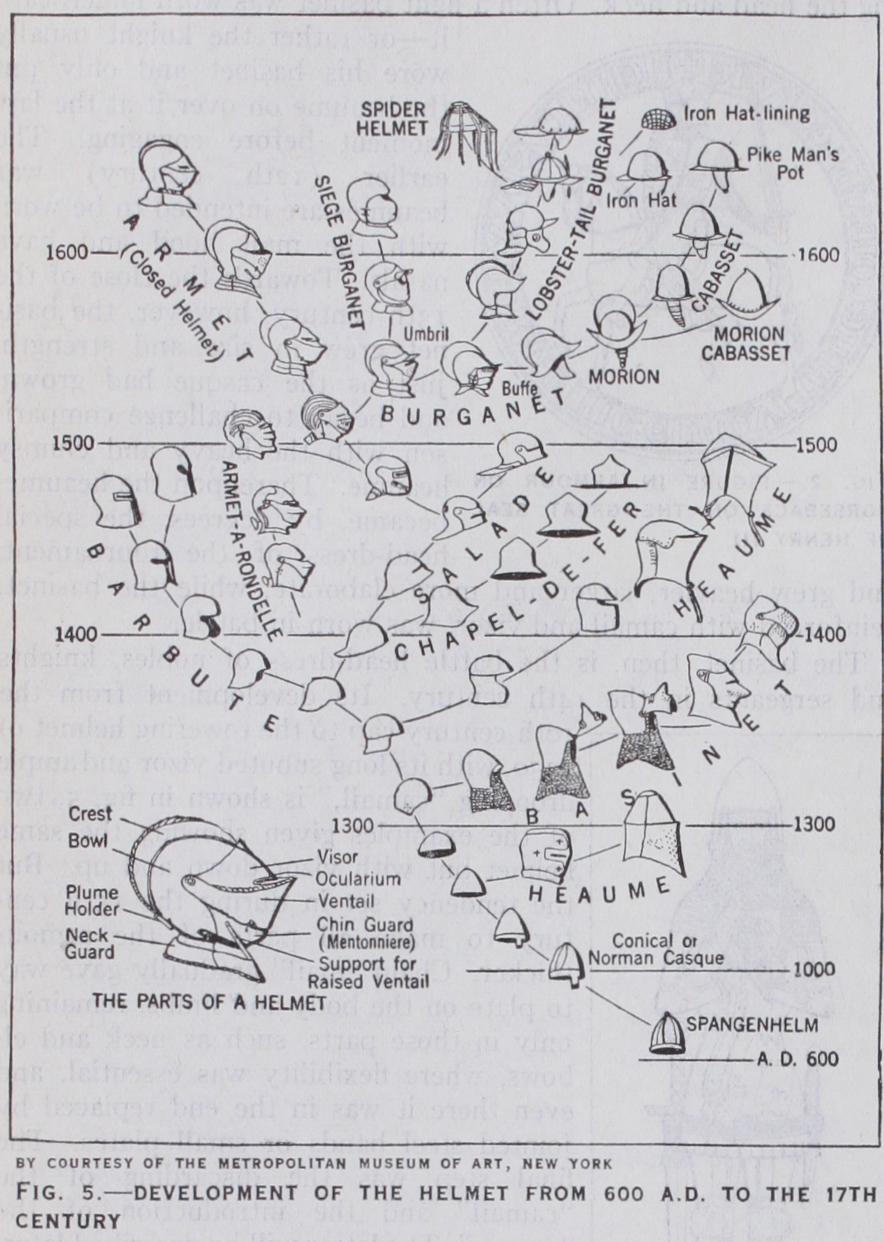

The head-dress of the warriors of the dark ages and of the earlier feudal period was far from being the elaborate helmet which is associated in the imagi nation with the knight in armour and the tourney. It was a mere casque, a cap with or without additional safeguards for the ears, the nape of the neck and the nose (fig. 1). By those war riors who possessed the means to equip and protect themselves more fully, the casque was worn over a hood of mail. In manu scripts, armoured men are some times portrayed fighting in their hoods, without casques, basinets or other form of helmet. The casque was, of course, normally of plate, but in some instances it was a strong leather cap covered with mail or imbricated plates. The most advanced form of this early helmet is the conical steel or iron cap with nasal ; it was worn in conjunction with the hood of mail. This is the typical helmet of the II th-century warrior, and is made familiar by the Bayeux Tapestry. From this point however (c. i ioo) the evolution of war head-gear follows two different paths for many years. On the one hand the simple casque easily transformed itself into the basinet, originally a pointed iron skull-cap without nasal, ear guards, etc. On the other hand the knight in armour, especially after the fashion of the tournament set in, found the mere cap with nasal insufficient, and the heaume (or "helmet") gradually came into vogue. This was in principle a large heavy iron pot cover ing the head and neck. Often a light basinet was worn underneath it—or rather the knight usually wore his basinet and only put the heaume on over it at the last moment before engaging. The earlier (i 2th century) war heaumes are intended to be worn with the mail hood and have nasals. Towards the close of the 13th century, however, the basi net grew in size and strength, just as the casque had grown, and began to challenge compari son with the heavy and clumsy heaume. Thereupon the heaume, became, by degrees, the special head-dress of the tournament, and grew heavier, larger and more elaborate, while the basinet, reinforced with camail and vizor, was worn in battle.

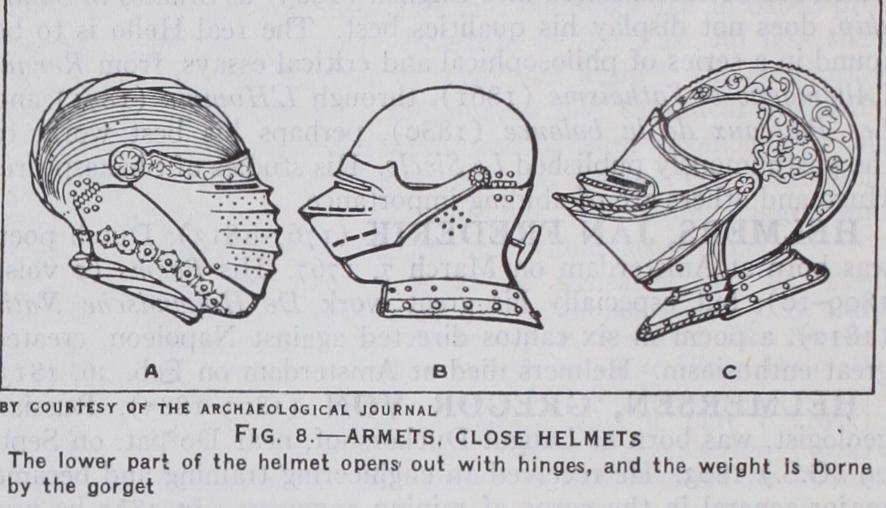

The basinet, then, is the battle head-dress of nobles, knights and sergeants in the 14th century. Its development from the ioth-century cap to the towering helmet of 13 5o, with its long snouted vizor and ample drooping "camail," is shown in fig. 5, two of the examples given showing the same helmet but with vizor down and up. But the tendency set in during the 15th tury to make all parts of the armour thicker. Chain "mail" gradually gave way to plate on the body and limbs, remaining only in those parts, such as neck and bows, where flexibility was essential, and even there it was in the end replaced by jointed steel bands or small plates. The final step was the discarding of the "camail" and the introduction of the "armet." The latter will be described later. Soon after the beginning of the 15th tury the high-crowned basinet gave place to the salade or sallet, a helmet with a low rounded crown and a long brim or guard at the back. This was the typical head-piece of the last half of the Hundred Years' War as the vizored basinet had been of the first. Like the basinet it was worn in a simple form by archers and pikemen and in a more elaborate form by knights and at-arms. The larger and heavier salades were also often used stead of the heaume in tournaments. Here again, however, there is a great difference between those worn by light armed men, foot-soldiers and archers and those of the heavy cavalry. The former, while sessing as a rule the bowl shape and the lip or brim of the type, and always destitute of the conical point which is the guishing mark of the basinet, are cut away in front of the face (fig. 7a) . In some cases this was remedied in part by the addition of a small pivoted vizor, which, however, could not protect the throat. In the larger salades of the heavy cavalry the wide brim served to protect the whole head, a slit being made in that part of the brim which came in front of the eyes (in some examples the whole of the front part of the brim was made movable). But the chin and neck, directly opposed to the enemy's blows, were scarcely protected at all, and with these helmets, a large volant-piece or beaver (mentonniere) usually a continuation of the body armour up to the chin or even beyond—was worn for this purpose, as shown in fig. 7b. This arrangement combined, in a rough way, the advantages of freedom of movement for the head with adequate protection for the neck and lower part of the face. The armet, which came into use about 1475-1 50o and completely superseded the salade, realized these requirements far better, and later at the zenith of the armourer's art (about 152o) and throughout the period of the decline of armour it remained the standard pattern of helmet, whether for war or for tournament. It figures indeed in nearly all portraits of kings, nobles and soldiers up to the time of Frederick the Great, appearing with the suits of armour or half-armour worn by the subjects, and also in allegorical trophies, etc. The armet was a fairly close-fitting rounded shell of iron or steel, with a mov able vizor in front and complete plating over chin, ears and neck, the latter replac ing the mentonnierre or beaver. The armet was connected to the rest of the suit by the gorget, which was usually of thin laminated steel plates. With a good armet and gorget there was no weak point for the enemy's sword to attack, a roped lower edge of the armet generally fitting into a sort of flange round the top of the gorget. Thus, and in other and slightly different ways, was solved the problem which in the early days of plate armour had been attempted by the clumsy heaume and the flexible, if tough, camail of the vizored basinet, and still more clumsily in the succeeding period by the salade, and its grotesque mentonniere. As existing examples show, the wide-brimmed sallet (salade or sallad) gave way to the rounded armet, the men tonniero being carried up to the level of the eyes. Then the use (growing throughout the 15th century) of laminated armour for the joints of the harness probably suggested the gorget, and once this was applied to the lower edge of the armet by a satisfactory joint, it was an easy step to the elaborate pivoted vizor which com pleted the new head-dress. Types of armets are shown in fig. 8.

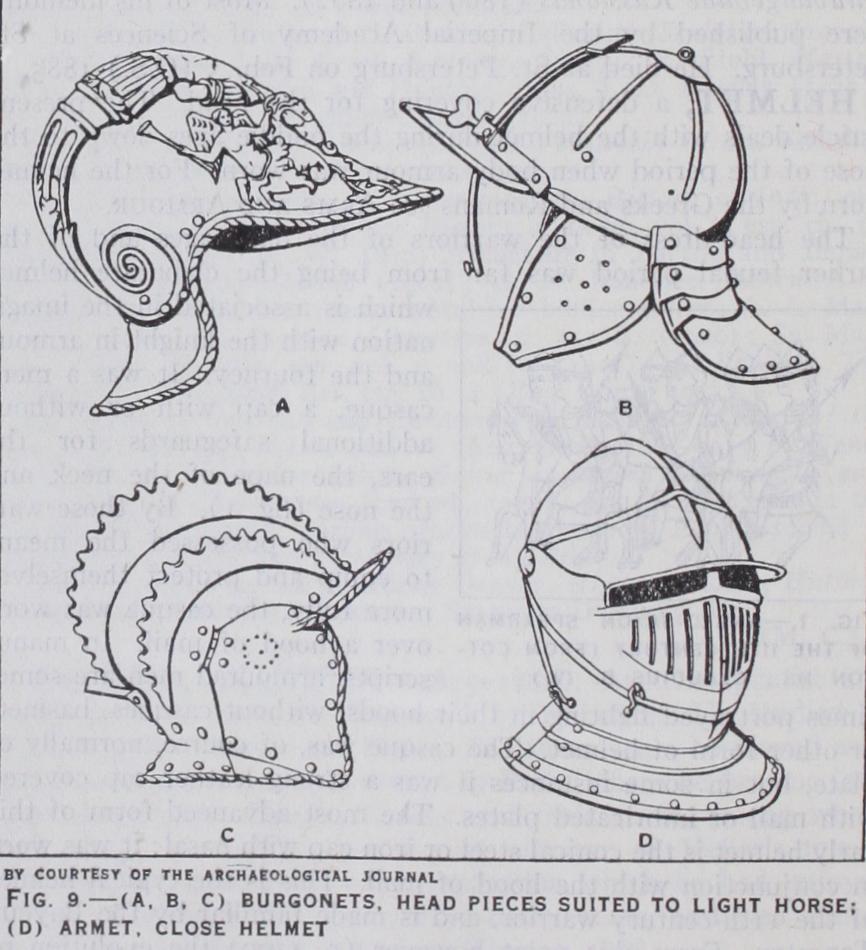

The burgonet or burganet, often confused with the armet, is typical of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In its simple form it was worn by the foot and light cavalry—though the latter must not be held to include the pistol-armed chevaux-legers of the wars of religion, these being clad in half-armour and vizored burgonet—and consisted of a (generally rounded) cap with a projecting brim shielding the eyes, a neck-guard and ear pieces. It had almost invariably a crest or comb, as shown in the illustrations (fig. 9) . Other forms of infantry headgear much in vogue in the i6th century were the morion and cabasset, both lighter and smaller than the burgonet ; indeed, much of their popularity was due to the ease with which they were worn or put on and off, for in the matter of protection they could not compare with the burgonet, which in one form or another was used by alry (and often by pikemen) up to the final disappearance of armour from the field of battle about 167o. A richly decorated i 6th-century Italian burgonet is in Vienna. Its archetype is per haps the casque worn by the Swiss infantry at the epoch of Mar ignan (1515) . This was probably copied by them from their former Burgundian antagonists, whose connection with this helmet is sufficiently indicated by its name. The lower part of the more elaborate burgonets worn by nobles and cavalrymen is often formed into a complete covering for the ears, cheek and chin, con nected closely with the gorget.

They therefore resemble the armets and have often been con fused with them, but the dis tinguishing feature of the bur gonet is invariably the front peak.

Various forms of vizor were fit ted to such helmets; these as a rule were fixed bars or continua tions of the chin piece. Often a nasal was the only face protec tion. The latest-form burgonet in active service is the familiar Cromwellian cavalry helmet with its straight brim, from which depends the slight vizor of three bars or stout wires joined together at the bottom.

The above are of course only the main types. Some writers class all remaining examples either as casques or as "war-hats," the latter term conveniently covering all those helmets which resemble in any way the head-gear of civil life. For illustra tions of many curiosities of this sort, including the famous iron hat of King Charles I. of England, and also for examples of Russian, Mongolian, Indian and Chinese helmets, the reader is referred to pp. 262-269 and 285-286 of Demmin's Arms and Armour (English edition Modern Steel Helmets.—During the World War the condi tions of trench warfare left the head exposed to danger more than any other part of the body. In addition to this the increased employment of shrapnel against troops caused the proportion of head wounds to rise considerably. To meet these circumstances the French devised a steel helmet weighing 22 oz. and brought it into use in the spring of 1915. It afforded comparatively slight protection, being capable of resisting a shrapnel bullet, 41 to the pound, fired to give a striking velocity of 40o ft. per second. The British authorities followed suit and after experiments, in Octo ber 1915, produced a helmet of hardened manganese steel weigh ing 21 oz. and capable of resisting shrapnel at 7 5o ft. per second. This helmet had the effect of reducing head wounds by 75% of what had formerly been ex perienced during the war. This gratifying result justified the ac celeration of the rate of issue and by July 1916, a million hel mets had been delivered to the B.E.F. in France. Later, over a million and a half British made helmets were supplied to the American forces. Helmets of this pattern were also issued to spe cial constables at home for pro tection against shrapnel from anti-aircraft barrage. The Belgian forces adopted the French pat tern. It was not until the summer of 1915 that Germany began to consider the matter of steel hel mets, the impetus to the idea being supplied by Professor Friedrich Schwerd of Hanover. Schwerd was given a free hand and by the end of 1915 after many experiments had produced a satisfactory helmet, the first of which were used by the shock troops (Stosstruppen) at Verdun in January 1916. They were made from chrome-nickel-steel and weighed approximately 2 lb. 3 oz. The shape was chosen to ensure a maximum ricochet effect with rifle bullets, These steel helmets have become a permanent part of the soldier's equipment in most armies.