Hemiptera

HEMIPTERA (Gr. *tit half and Irrepov a wing), the name applied in zoological classification to that order of insects (q.v.) which includes plant-bugs, cicadas, aphides and scale insects.

The name was first given by Linnaeus (173 5) who applied it in allusion to the half-coriaceous and half-membranous character of the fore-wings in many species of the order. This expression, however, is not very well suited as the fore-wings in many mem bers are of a uniform texture, and the most characteristic feature is afforded by the mouth-parts which form a beak-like proboscis with piercing and sucking stylets. This latter feature led J. C. Fabricius (1775) to substitute the name Rhynchota (Rhyngota) which is still used by many authorities. Hemiptera number about 36,00o described species; the great majority are plant feeders and rank among the most destructive of all insects. Two pairs of wings are generally present, the anterior pair being most often of harder consistency than the posterior pair, or with the apical region more membranous than the remainder. The mouth-parts are always adapted for sucking and piercing and the palpi are atrophied. Metamorphosis is incomplete (fig. 13) in most cases but, more rarely, complete in certain others (fig. 14). Collec tively the members of the order are known as plant-bugs : most of them are of small or moderate size while a few, such as the giant water-bugs and cicadas are very large insects. The prevail ing type of colouration is green, but cicadas, lantern flies and their allies, and cotton stainers are often conspicuously coloured.

General Structure.

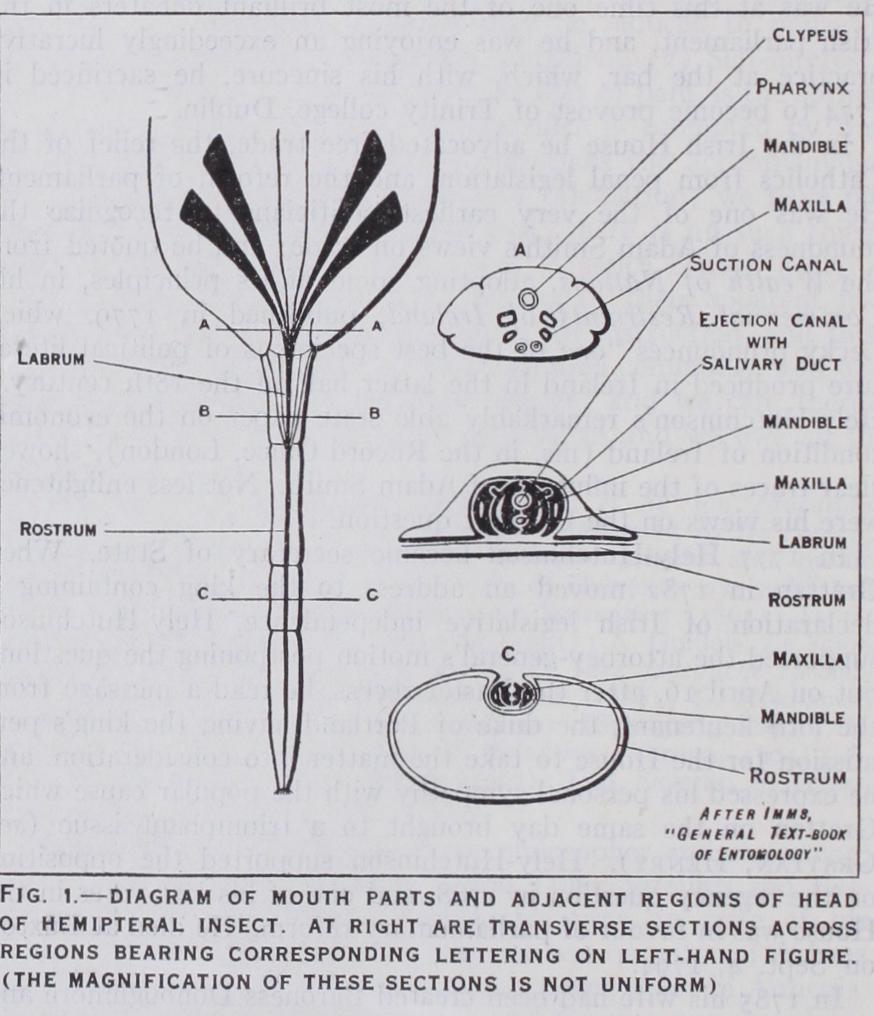

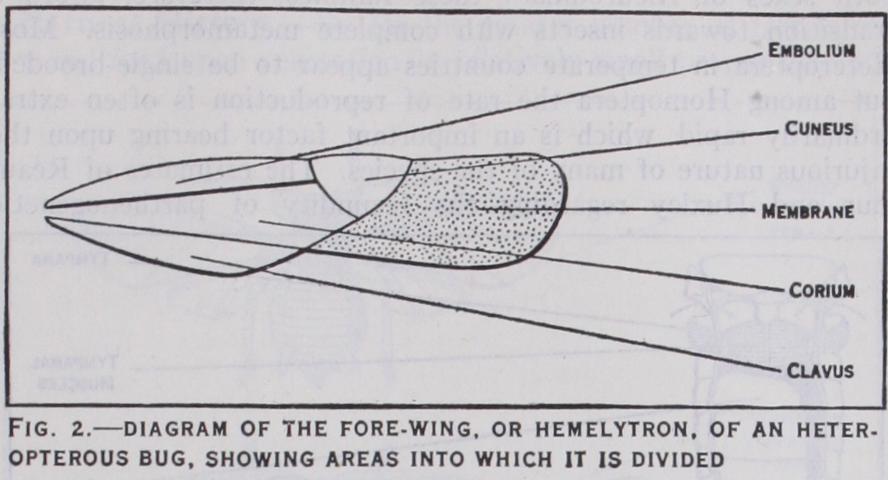

The head is very variable in form and in most cases the sclerites are compactly fused with few notice able sutures. As a rule the antennae have only four or five joints but in exceptional cases Io (Psyllidae) or even 25 joints (males of a few Coccidae) may be present. The mouth-parts are of an exceptionally uniform character throughout the order, a feature that is correlated with the universal habit of feeding by means of piercing and sucking. The mandibles and maxillae are in the form of needle-like stylets and are intimately held together so as to function almost as one organ (fig. 1) . Each maxilla bears two grooves separated by a longitudinal ridge and the two maxil lae are locked together so that the grooves form a pair of minute tubes. The upper tube so formed is the suction canal through which the food is imbibed, while the lower tube allows for the flow of the saliva into the plant and is hence termed the ejection canal. The labium takes the form of a jointed sheath or rostrum which is grooved above to form a slot in which the other mouth parts repose when at rest. The labium takes no part in feeding, and both pairs of palpi are wanting. In many members of the order the pronotum is a large conspicuous shield as in beetles, the legs have three or fewer joints to the tarsi and the wings are exceedingly variable in character with relatively scanty venation. In the sub-order Heteroptera the forewings are termed hemelytra (hemi-elytra) and their proximal area is horny or leathery, re sembling an elytron, only the distal portion remaining membra nous. The hind wings are always membranous and in repose are folded beneath the hemelytra. The hardened basal portion of the hemelytron is divided into a narrow posterior area or clavus and a broader main portion or corium. In some cases a narrow strip of the corium is marked off along the anterior margin to form the embolium and in Capsid bugs there is a triangular apical area to the corium which is termed the cuneus (fig. 2) . In the sub-order Homoptera the wings are of uniform texture and frequently of harder consistency than the hind pair. Many bers of the order are wingless, especially in aphides and the males of all scale insects. In other cases there are several de grees of wing development within a single species—wingless, fully-winged and half-winged individuals being present. The mean ing of this wing-polymorphism is obscure. The abdomen some times exhibits indications of II segments, but reduction or sup pression of one or more is the rule. In some water-bugs a true ovipositor is well developed but in other groups it is inconspicu ous or wanting.

Classification.

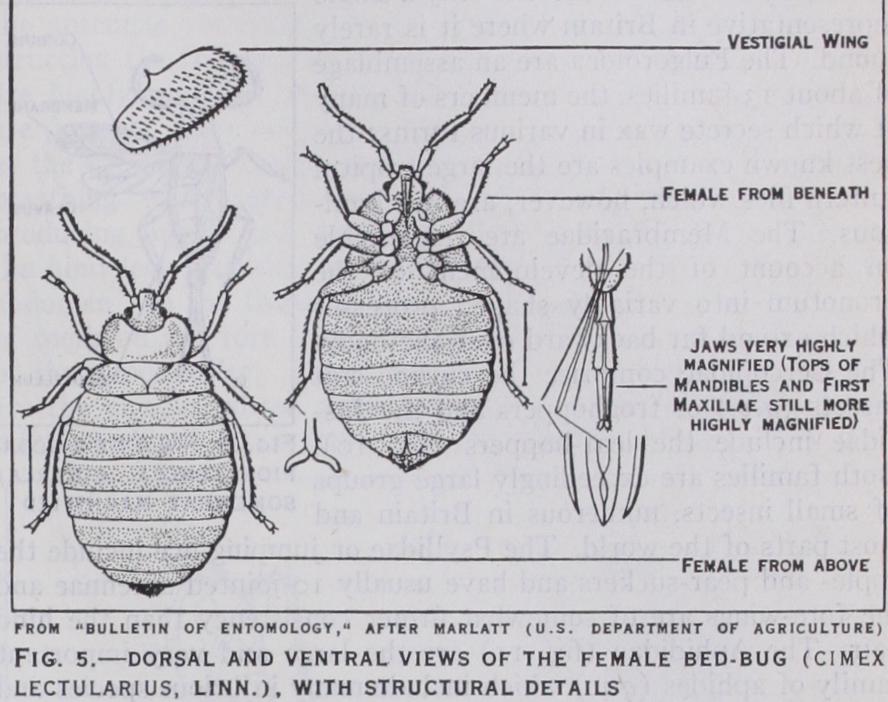

Plant bugs are divided into a large number of families which are grouped under two sub-orders as given below : I. HETEROPTERA Wings generally overlapping on the body when at rest, the fore-pair usually hardened, the apex only being membranous. Pronotum large ; tarsi generally 3-jointed. The Heteroptera in clude both terrestrial and aquatic families the most important of which are the following:— Series I. GYMNOCERATA.-An - - - - -- tennae conspicuous ; terrestrial or in some cases living on the surface of water. The Pentatomidae or shield bugs are rather large and often brightly coloured insects, characterised by the great size of the scutellum which sometimes covers the abdomen (fig. 3) . The Coreidae have a smaller scutel lum and the antennae are placed high upon the head : the squash bug (Anasa tristis) of the U.S. is a well known example. The Lygaeidae are related to them, but the antennae are placed lower on the head : the American chinch bug (Blissus leucopterus) is well known and the family includes about 5o British species. The Pyrrhocoridae or red bugs differ from Lygaeidae in having no ocelli; most species have bright red, or green, and black colora tion and the injurious cotton-stainers (Dysdercus) are well known examples. The Tingidae or lacebugs are small creatures, whose integument exhibits a beautiful net-like pattern and the tarsi are 2-jointed. The Hydrometridae are a large family of pond-skaters which are clothed below with silvery pubescence : the genus Halobates and its allies (fig. 4) occur far out on the ocean in warm latitudes. The Reduviidae are a family of over 2,000 species, with a prominently curved rostrum: they mostly live on the blood of other insects, while species of Triatoma and Reduvius suck the blood of man. The Cimicidae (fig. 5) are the well known bed-bugs (Cimex) which are blood-suckers of mam mals and birds and the Polyctenidae are curious parasites living on bats. The Capsidae are a large family in which the hemelytra have a cuneus, but no embolium (fig. 6) : over 18o species are British and some are serious ene mies of fruit trees.

Series II. CRYPTOCERATA.--- Aquatic species with concealed antennae. Included here are the Belostomatidae or giant water bugs of the Tropics which may exceed 4in. in length. They feed upon small fish, tadpoles and other insects, but often take to the wing and are attracted to lights at night. The Nepidae or water scorpions (fig. 7) have an apical breathing tube at the ex tremity of the abdomen, rapto rial forelegs and 3-jointed an tennae. The Notonectidae or water-boatmen (q.v.) swim on their backs by means of their strong oar-like legs and when diving carry a supply of air beneath the wings. They are markedly predaceous and can inflict painful punctures when handled. The Corixidae are numerous in most countries, and are largely bottom-dwellers notable for their faculty of stridulation.

II. HOMOPT

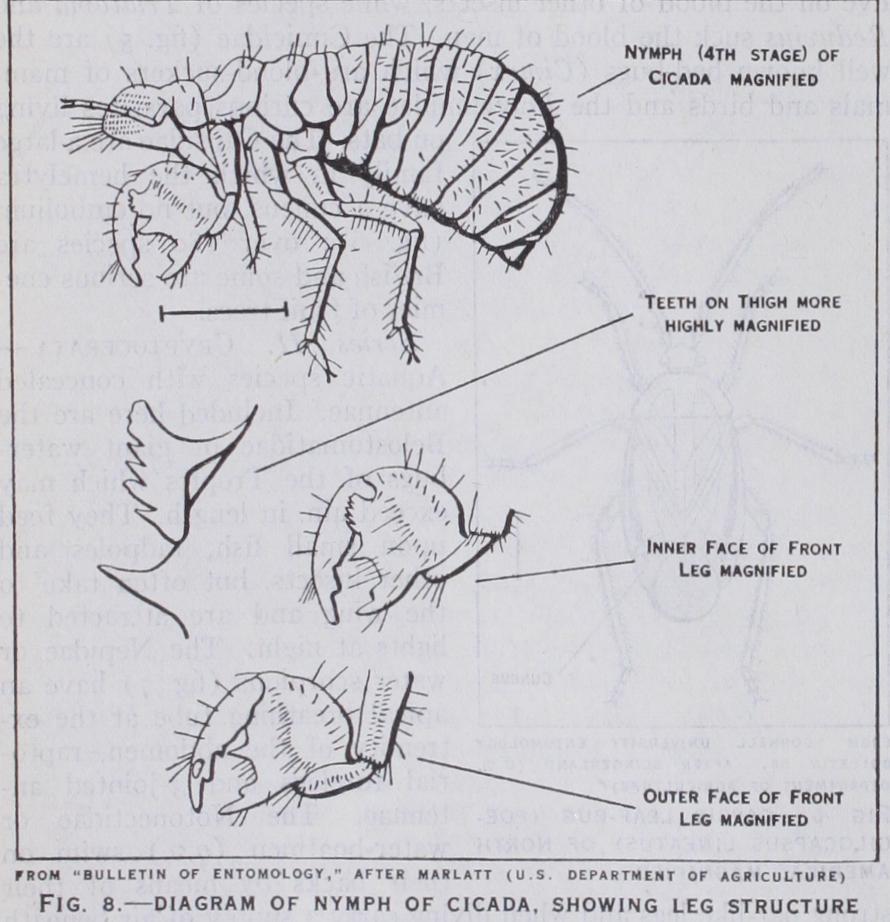

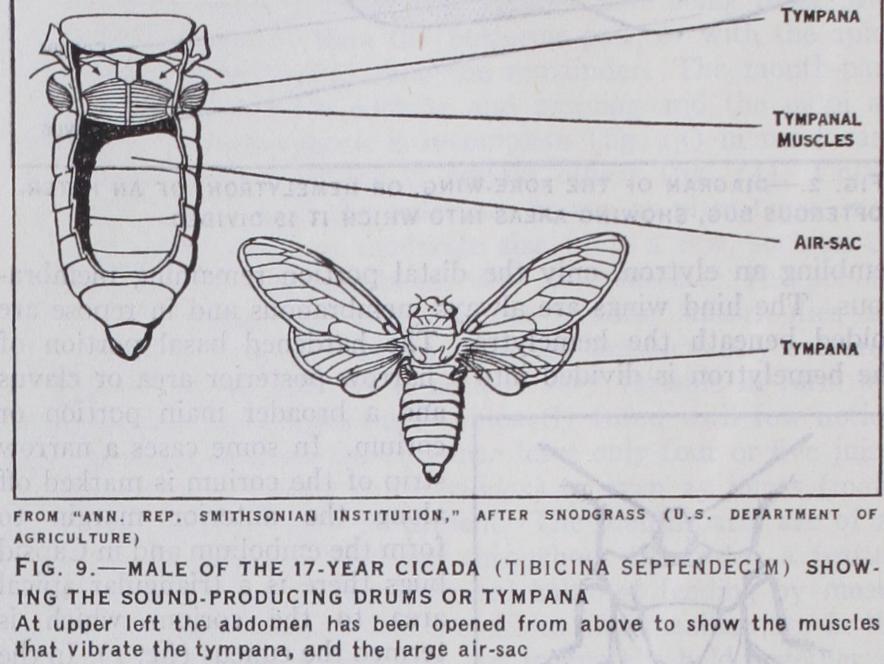

ERA Wings usually sloping roof-wise over the sides of the body when at rest, the fore-pair of uniform consistency, but wingless forms are frequent. Pronotum small, tarsi I- to 3-jointed. By far the greater number of the Hemiptera belong to this sub-order and, with the exception of the cicadas and lantern flies, they are mostly small or very small, fragile insects. The Cicadidae or cicadas (q.v.) include over i,000 species of large insects with ample membranous wings and toothed femora to the fore-legs. The males almost always have a sound-producing apparatus on each side of the base of the abdomen (fig. 9) and are very power ful stridulators. The nymphs (fig. 8) live below ground at the roots of plants. The family is mainly tropical : 74 species occur in North America but there is only a single representative in Britain where it is rarely found. The Fulgoroidea are an assemblage of about 13 families, the members of many of which secrete wax in various forms: the best known examples are the large tropical lantern flies which, however, are not lumi nous. The Membracidae are remarkable on account of the development of the pronotum into variably shaped processes which extend far backward over the body.The Cercopidae comprise the cuckoo spit insects (q.v.) or froghoppers and the Jas sidae include the leaf-hoppers (fig. 1o).

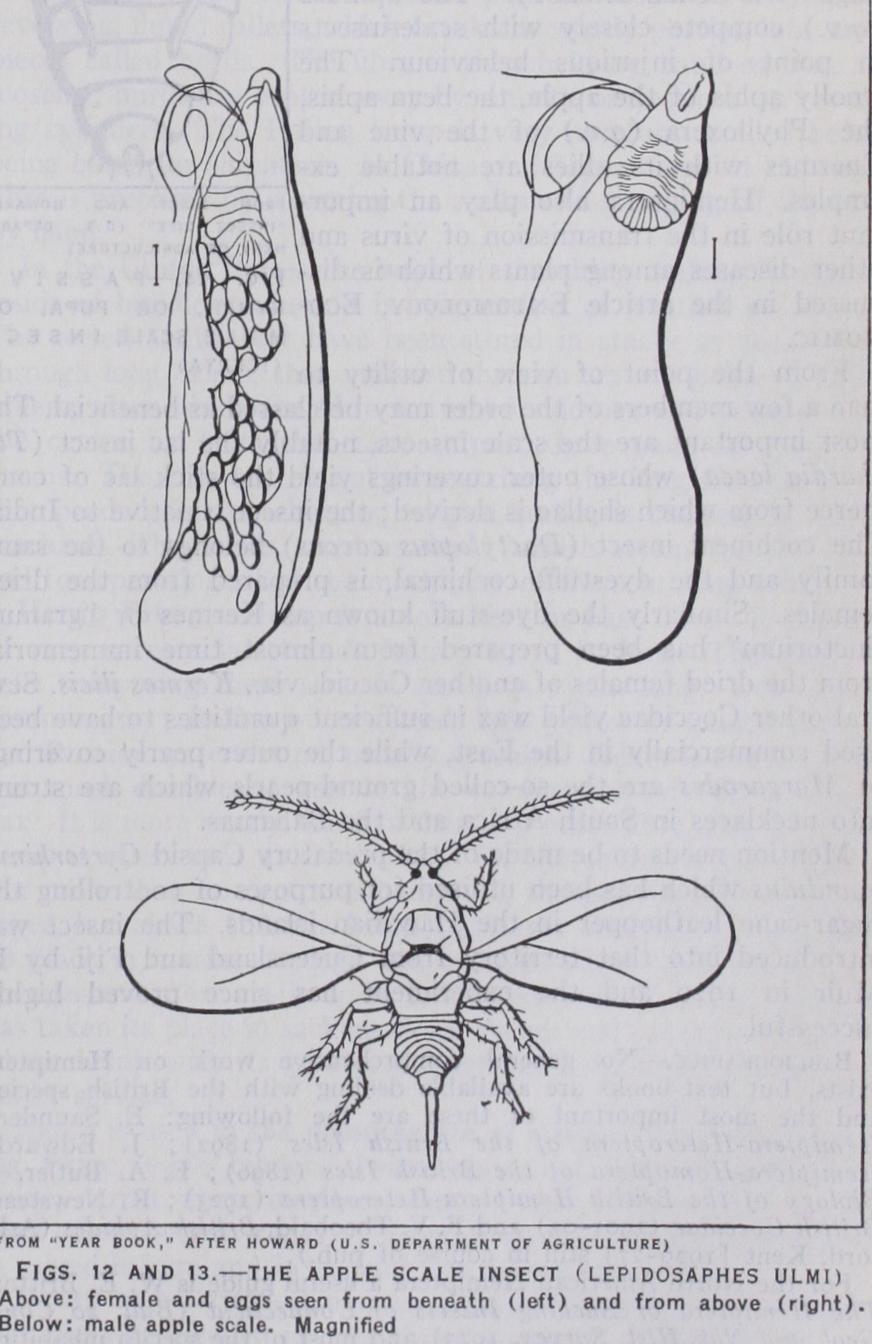

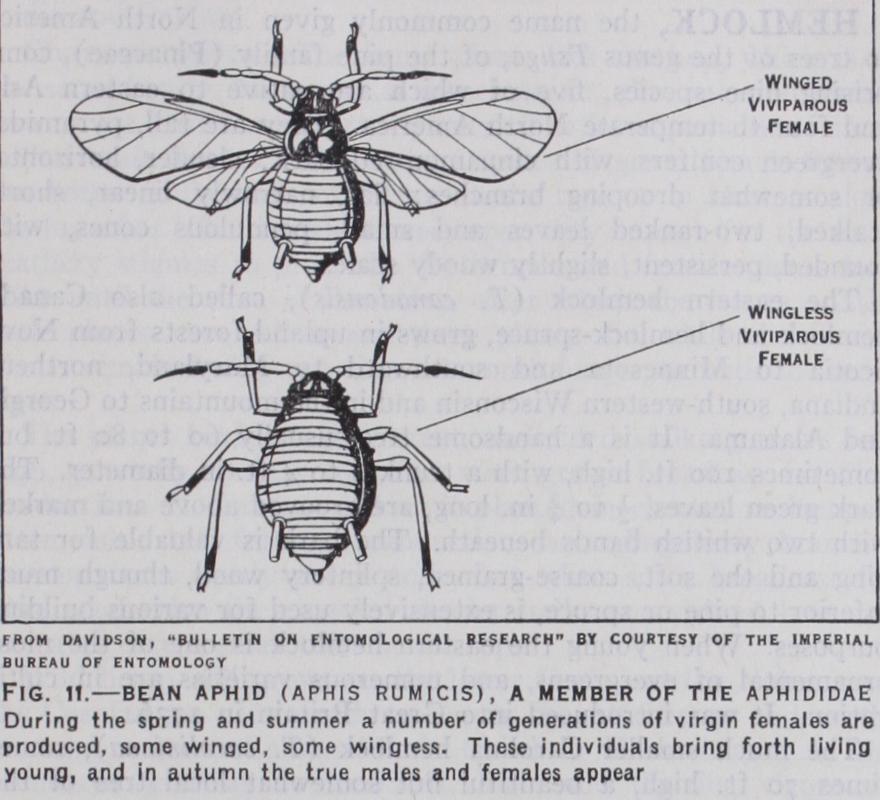

Both families are exceedingly large groups of small insects, numerous in Britain and most parts of the world. The Psyllidae or jumping lice include the apple- and pear-suckers and have usually io-jointed antennae and the fore-wings are of somewhat firmer consistency than the hind pair. The Aphididae (fig. i i) are the large and very important family of aphides (q.v.) which include many injurious species and undergo a highly complex life-cycle: among the best known forms are the woolly aphis of the apple and the vine Phylloxera (q.v.). The Aleurodidae or white flies are minute fragile creatures dusted with a waxy powder: the greenhouse white-fly (Asterochiton vaporarioruyn) is the only species likely to attract notice. The Coccidae (fig. i 2) form one of most noxious groups of all insects and include the scale insects (q.v.) and mealy bugs. The females are degenerate wingless insects and cause most of the damage entailed by this family, while the males are very fragile creatures with a single pair of wings and no mouth-parts.

Reproduction and Development.

In most Hemiptera the nymphs resemble the parents except for the absence of wings and they are active through all stages of growth, feeding in a manner similar to the adults. The number of moults undergone is very variable and the wing-rudiments appear among Heteroptera about the fourth instar (fig. 13) . Cicadas are remarkable because the young insects are adapted for burrowing, and suck the sap from roots, while the adults are aerial. In male Coccidae an incipient pupal stage is passed through (fig. 14) and the same occurs in both sexes of Aleurodidae : these families, therefore, afford a transition towards insects with complete metamorphosis. Most Heteroptera in temperate countries appear to be single-brooded, but among Homoptera the rate of reproduction is often extra ordinarily rapid, which is an important factor bearing upon the injurious nature of many of the species. The estimates of Reau mur and Huxley regarding the fecundity of parthenogenetic aphides are well known. Buckton, on the other hand, thinks that they are placed too low and he states that the progeny of a single aphid at the end of 30o days (if all members survived) would be the i 5th power of 210 ! R. C. L. Perkins mentions with regard to leaf-hoppers, that if each hopper lays 5o eggs, and the sexes are about equal in number of individuals, in six generations the progeny of one female would amount at the end of the season to 500,000,000. Fortunately climatic changes, parasites and pred ators collectively maintain the proper balance of such prolific creatures by destroying them in vast numbers.

Geographical Distribution. —Although very widely distrib uted, Hemiptera have not pene trated as far into remote and in hospitable regions as have some of the other orders. The Ful goroidea and Cicadidae are more especially tropical groups and the Membracidae attain their greatest development in Central and South America, but many of the other large families are well represented in most countries. Some species such as the bed bug (Cimex lectularius) and the shield bug, Ncsara viridula, are nearly world-wide and a num ber of European species have found their way into North America.

Geological Distribution.

Hemiptera first appear in geolog ical times in Lower Permian rocks of Kansas and Germany. The remarkable German fossil Eugeron has the typical Hemipterous mouth-parts except that the labium is paired and unfused, while the wing-venation is more like that of an early cockroach type. On these characters Eugeron has been referred to a separate extinct order, the Protohemiptera. In the Kansas rocks un doubted Homoptera occur, belonging to extinct families and the first Heteroptera appear in the Upper Trias of Ipswich (Aus tralia), where they are represented by forms possibly ancestral to shield bugs and water-boatmen. In Jurassic times both sub orders are well represented and some of the dominant existing families differentiated. After the Jurassic period Hemiptera become more abundant as fossils, notably in the Miocene of Florissant and in Baltic amber.

Natural History.

By far the greater number of Hemiptera live and feed upon vegetation : a relatively small proportion suck the body-fluids of other insects or the blood of mammals and birds. The vegetable feeders may live on any part of a plant: aphides tend to congregate on the young sappy shoots, while a few live at the roots: scale-insects often heavily infest the bark, but there are many other kinds found on the leaves and fruit and some on the roots, while leafhoppers and frog-hoppers are abundant on almost all kinds of vegetation. A few species of aphides, scale-insects and Psyllidae form galls but the habit is rare within the order. The carnivorous members mostly prey upon other forms of insect life and this habit is characteristic of the family Reduviidae and of most of the water-bugs : some of the large species of the latter also attack tadpoles and small fish. Other of the carnivorous bugs subsist upon the blood of verte brates. Members of the genus Triatoma (Reduviidae) are vora cious blood-suckers in the Tropics and the species T. megista is the main carrier of the Trypanosome of a fatal human disease in South America. The bed-bugs (Cimex) infest man in most parts of the world where he is living under unhygienic conditions, while certain other members of the same family suck the blood of birds. Members of the curious tropical family Polyctenidae in clude about 20 species of wingless insects, which live deep down among the fur and suck the blood of bats : they are also remark able in being viviparous, the young being brought forth relatively advanced in development.

Whatever their habits may be, all Hemiptera, upon emerging from the egg, live by piercing the plant or animal host, as the case may be, with their mouth-stylets. Their food always con sists of fluids, either sap or blood and with the plant-feeders penetration of the tissues by the stylets is facilitated by the presence of enzymes in the insects' saliva. In some cases it ap pears that such enzymes are able to dissolve parts of the cell walls and liquefy the surrounding tissues : and often the actual punctures are indicated by areas of discoloured necrotic cells. In some Hemiptera the saliva contains an enzyme which converts starch into sugar and, among many Homoptera, there appears to be an excess of sugars in their diet which is repeatedly voided in fluid drops from the anus in the form of honey-dew. Scale in sects, aphides and Membracidae discharge large quantities of this material over the surrounding leaves which often become coated or discoloured by it. Honey-dew is very much sought after by ants which scour plants infested by these insects in order to im bibe it as it is actually being discharged. Some aphides are tended and sheltered by ants solely for the honey-dew they yield, while certain root-feeding Coccidae are tolerated in their nests for this same reason. Aquatic Hemiptera exhibit interesting adaptations for swimming and breathing in water. In the surface dwellers (Gymnocerata) these adaptations are less pronounced; the antennae are free and unconcealed, the legs not highly modi fied and these insects are clothed with a velvety pale below, which prevents wetting. The true aquatic forms (Cryptocerata) have the antennae concealed, the long antennae of surface forms ob structing the freedom of motion of submerged insects. The legs are highly modified as oars and various respiratory adaptations are present. They come to the surface to take in a supply of air at the caudal extremity, and this is retained in various ways for breathing while submerged. Many Hemiptera possess sound producing organs and among shield-bugs wart-like tubercles on the hind legs are scraped across a set of fine ridges beneath the abdomen. In the Corixidae sound is produced by drawing a row of teeth on the fore tarsus across a series of pegs on the femur of the opposite leg. The loudest and most notorious stridulators are the cicadas whose notes have been variously compared to a railway whistle or a scissor-grinder; when numerous the noise emitted by these insects is both trying and monotonous to human ears. It is produced by a pair of drums or membranes within the metathorax, which are worked by special muscles and the cavities within which they lie are usually protected by a prominent plate on either side of the base of the abdomen. Cicadas (q.v.) are further remarkable for the length of their life-history in the case of certain species, the "periodical cicada" of North America re quiring 13 to 17 years in order to complete its nymphal growth.