Highway

HIGHWAY. This word, which in England is used to indi cate any road of size and importance, has been specifically applied to a network of national roads in the United States with which this article is concerned. For the law of Highways see LAW OF HIGHWAY, THE.

As European peoples went to America they first settled along the seaboard. They therefore first used the sea and adjacent waterways for intercommunication. The few intercommunity roads then built, closely followed coast lines. Even as the desire to move inland developed, the vast waterways were used for transportation and roads were not required. The founders of the Republic, however, had the vision to see the future need of roads. In 178o George Washington conceived the building of a national road to the West and in 1802 Congress passed a financing act for that purpose on admitting Ohio into the Union. This was the beginning of the later building by the Federal Government of a road leading from Washington, D.C., to Santa Fe. This road, known variously as the "Cumberland road," the "National pike," "the Santa Fe trail," and now the "National Old Trails road" (q.v.), is the only national road built by the U.S. Government. As the country grew, needed transportation facilities were sup plied by the rapid extension of railroad mileage. Most road building was confined to centres of population and these early roads were mostly of soft dirt. Such intercommunity roads as were built were often financed by private capital through charters allowing the collection of tolls. These toll roads, beginning in were called "turnpikes" and were later built of broken stone crushed into place by passing horse-drawn vehicles. Some of these turnpikes like the Old York road from Philadelphia towards New York, the Baltimore and Lancaster pikes, also out of Philadelphia, remained until well after the close of the last century; but many of them were abandoned by 185o. Their financial failure was due to the development of steam railroads taking away their business.

With the advent of the bicycle came the organization in 188o of the League of American Wheelmen, the first national organiza tion to arouse general public interest to the need of improved roads. It gave an impetus to road building then done entirely by towns or townships and counties. New Jersey in 1891 first passed a law giving "State aid" to her counties to help them financially in carrying forward the building of good roads. By 1903, I I States were giving aid and ten years later in 1913, 42 States were giving aid. But even in 1913 most roads were being built around centres of population and not so much to connect those at any considerable distance from each other. The need for interstate roads was just beginning to be felt. Because of this need there arose a strong public demand that the U.S. Government should again contribute financially towards road building. This demand took definite form in 1916 in the passage by Congress of the first Federal aid bill providing for financial aid to the States to build roads, to be administered by the Department of Agriculture through the Bureau of Public Roads. When this bill was passed all but three States were giving aid and these did so the following year.

Until 1890 broken stone, gravel, shell and slag were about the only materials used for road surfacing. By 1904 there were about 150,00o m. of surfaced highways. Only 141 m. of these were of the higher type of bituminous, tar, asphalt or brick. But the motor vehicle was then beginning to indicate the need of hard and paved roadways. In 1928 there were about 600,000 m. of sur faced highways with 2.400,00o more miles of roads still of native soil to be improved. These surfaced roads had about 90,00o m. paved, 40,00o m. hard surfaced and 470,00o m. surfaced with material such as gravel, sand clay, sand oil and other types not paved or hard.

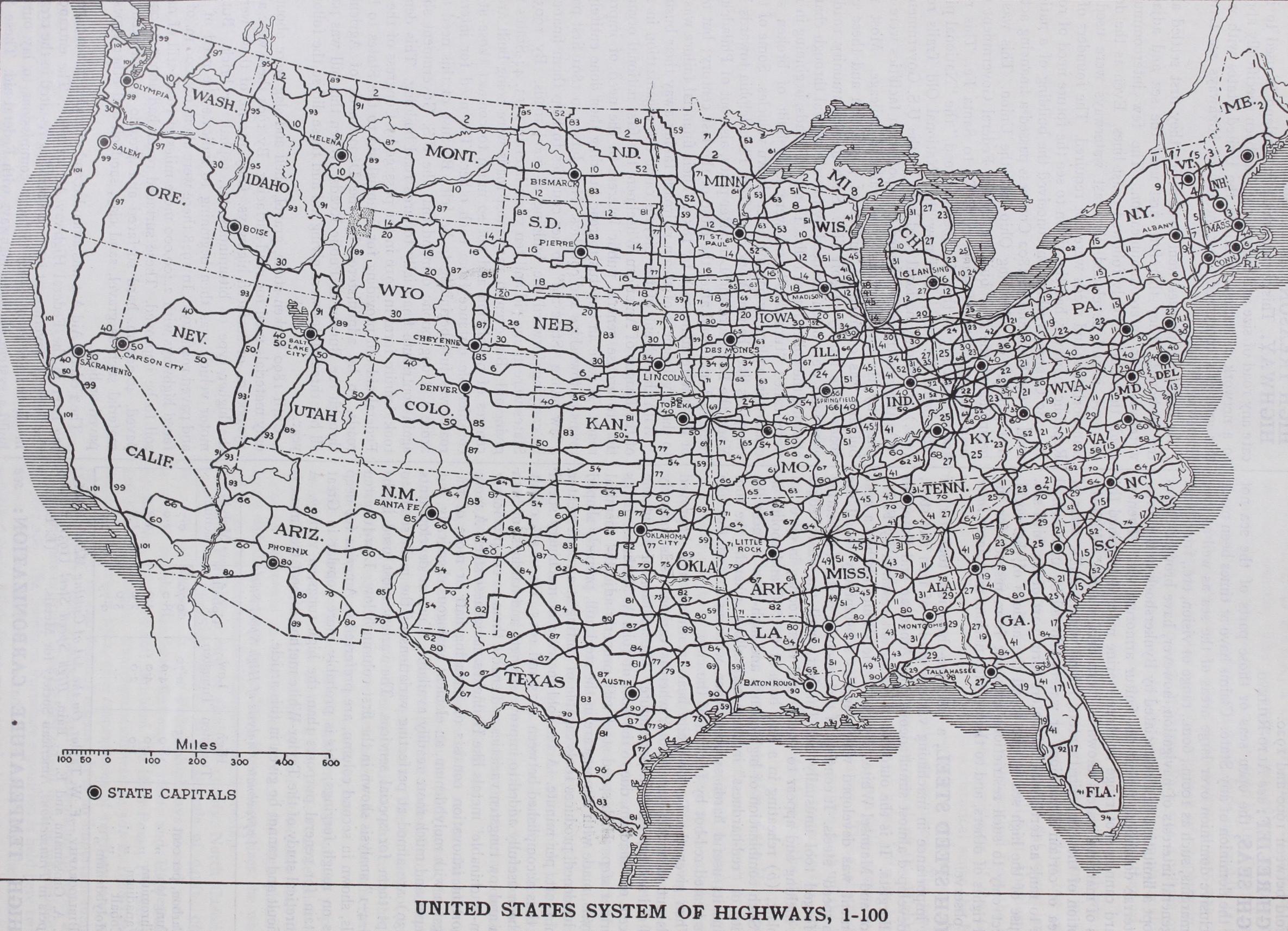

The Federal Aid Act was amended and extended in 1919, result ing later in the Federal Highway Act of 1921. The entrance of the Federal Government into road building resulted in the creation in all the States of State highway commissions to lay out and build a system of State highways with Federal aid. These State highways in 1928 aggregated about 300,00o m. to about 200,000 M. to which Federal aid contributed. Of this Federal aid mileage approximately Ioo,000 m. have been designated as "United States Highways" and are so marked and numbered with the shield of the United States. They are the primary trunk interstate high ways of the Nation.

Thousands of organizations were formed to advocate not only good roads in general but a specific good road in particular. By 1913 there were over 5o major good roads organizations and over 50o minor ones, while so-called trail associations, advocating the improvement of a particular through road, were being formed with surprising rapidity. In 1911 the National Highways Association was organized, and over io,000 organizations have since become members of or affiliated with this association.

The principal national highways (for fuller description see under separate headings) in the United States are the ocean to ocean highways : the National Old Trails road extending from Washington, D.C., to Los Angeles; the Lincoln highway extending across the north central United States; the Pikes Peak Ocean to Ocean highway from New York city to San Francisco; the Yellowstone trail from Plymouth rock on the Atlantic to Seattle on Puget sound; the Lee highway from Washington, D.C., to San Diego, Calif.; the Old Spanish trail from St. Augustine, Fla., to San Diego ; and the better known north and south alignments : the Atlantic highway from Maine to Florida ; the Dixie highway from Lake Michigan to Florida ; the Meridian road from Canada to Mexico ; and the Pacific highway from Vancouver, Canada, to the Mexican boundary line south of San Diego, Calif. (C. DAv.) HILARION, ST. (c. 290-371), abbot, the first to introduce monasticism into Palestine, was born of heathen parents at Ta batha near Gaza, and was educated at Alexandria where he became a Christian. About 306 he visited St. Anthony and, embracing the eremitical life, lived for many years as a hermit in the desert by the marshes on the Egyptian border. Many disciples put themselves under his guidance in south Palestine. In 356 he returned to Egypt ; but the accounts given in St. Jerome's Vita of his later travels must be taken with caution. It is there said that he went from Egypt to Sicily, and thence to Epidaurus, and finally to Cyprus where he met Epiphanius and died in 371.

See O. Zocker, "Hilarion von Gaza," Neue Jahrb. f. deutsche Theol. (1894) ; A. Butler, Lives of the Saints for Oct. 21, and Herzog-Hauck, Realencyklopddie.