Rio De Janeiro Cherbourg

CHERBOURG, RIO DE JANEIRO.

Classification.

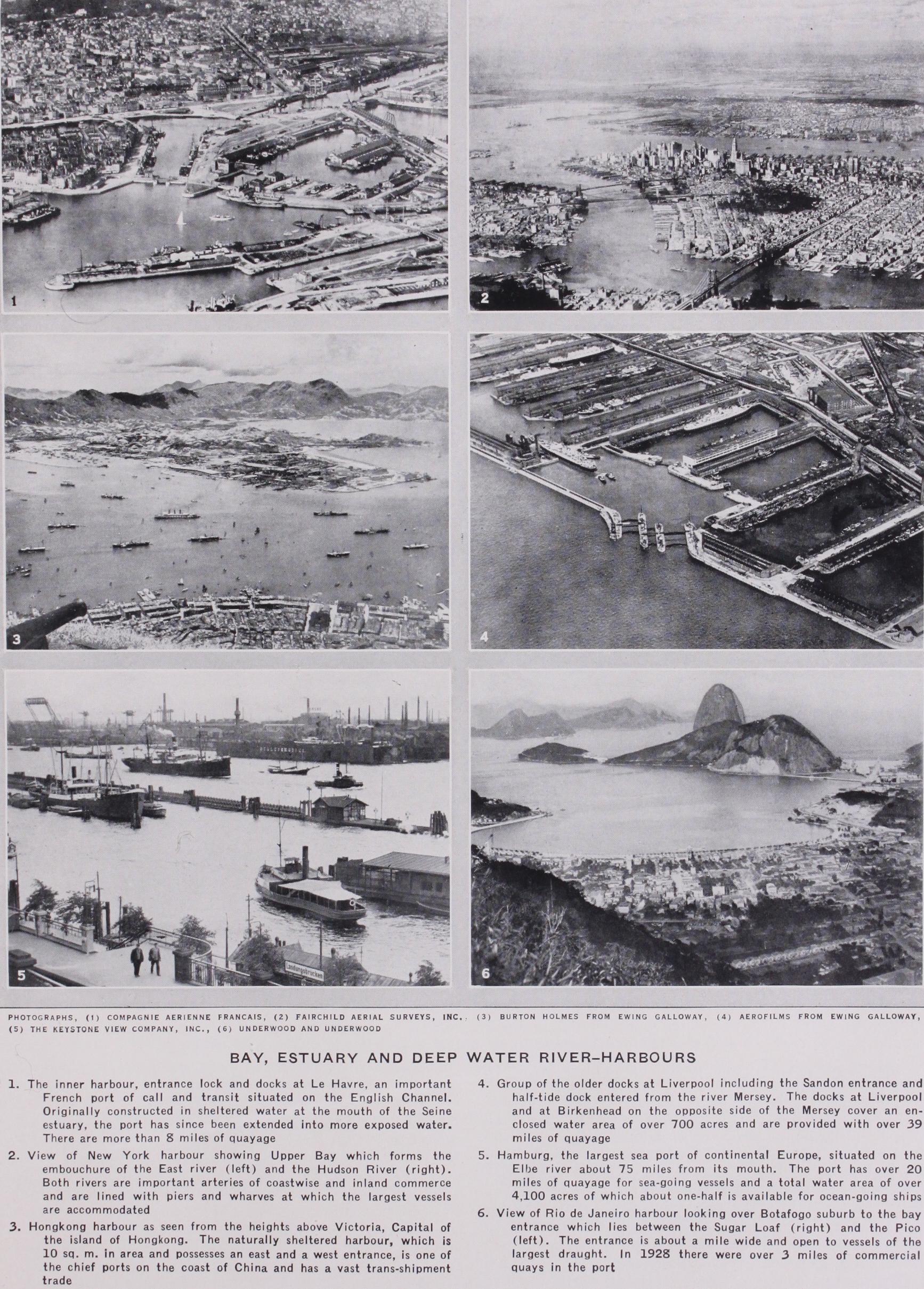

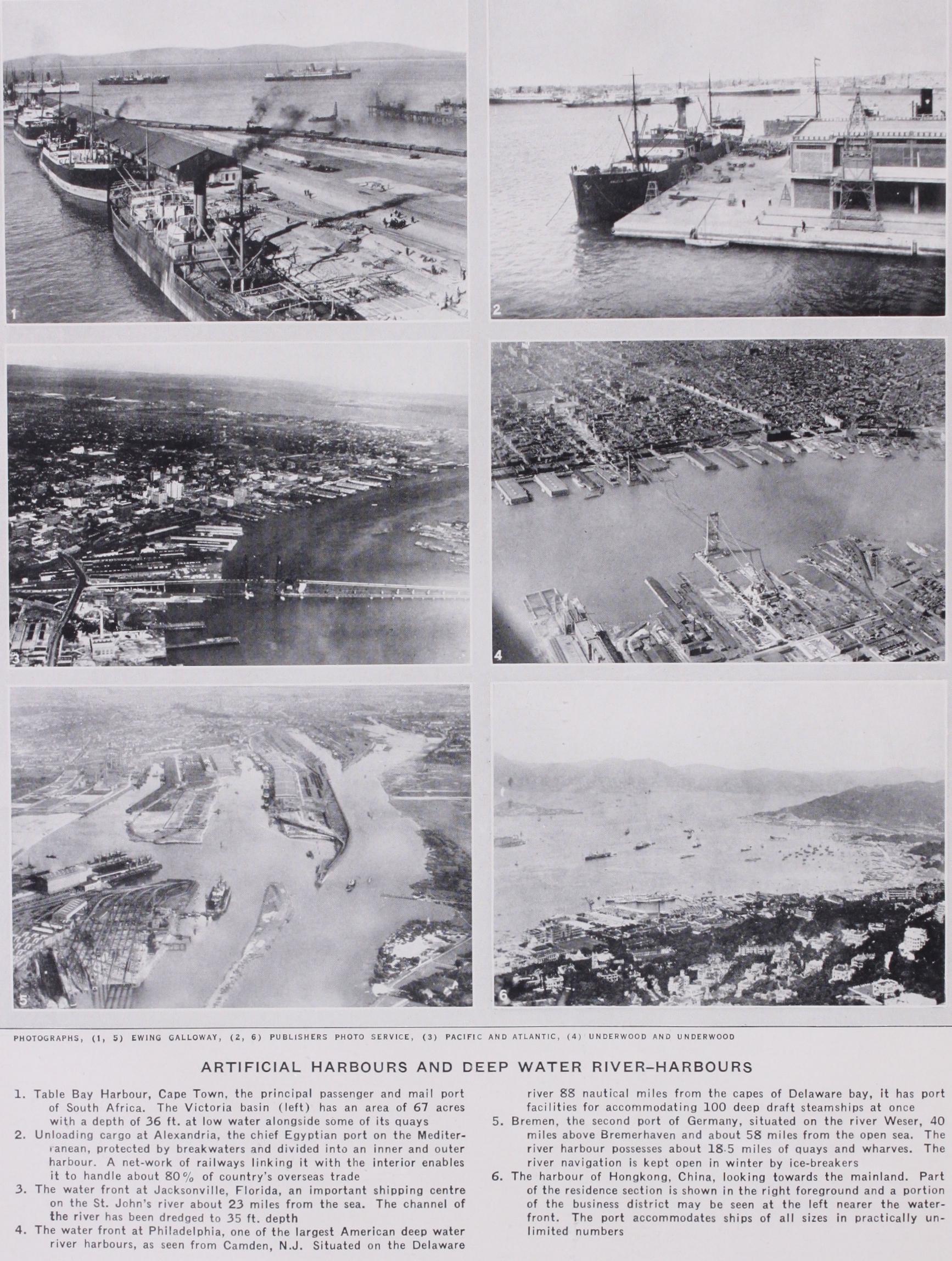

Harbours may be classified in several ways: 1. Natural harbours, possessing, in a large degree, natural shelter. These require only the provision of such facilities as docks or piers, and sometimes deepening by artificial means, to make them serviceable as shipping ports. Such are the land locked harbours of Hongkong, Rio de Janeiro, New York, Ports mouth and Sydney. Some estuarine harbours, such as those formed by the lower tidal compartments of the Thames, Mersey and Yangtse, also come under this heading.2. Harbours possessing partial natural shelter improved by arti ficial means, e.g., Plymouth and Table Bay.

3. Harbours entirely (or almost entirely) of an artificial nature formed on open sea coasts. A notable example of this class is Madras harbour (fig. 2).

Another classification, of an arbitrary and somewhat artificial nature, divides harbours according to their respective purposes, e.g., harbours of refuge, commercial harbours, naval harbours and fishery harbours. It may be explained here that the term "har bour of refuge" (now almost obsolete) ordinarily denotes a harbour constructed specifically and primarily for the purposes of shelter (usually for small craft), and not as an essential factor of a naval or commercial port.

Still another method classifies harbours according to their physical characteristics and the nature of the artificial works employed for their creation or improvement ; as for instance : (a) lagoon harbours, (b) jetty harbours, (c) harbours formed by converging breakwaters projected from the shore, (d) those pro tected by breakwaters parallel with the shore, (e) those formed by the projection of breakwaters from one or both horns of a bay, and (f) harbours where island breakwaters cover and protect embayments.

There is no conclusive evidence as to the date or the locality of the first artificial harbour construction. The use of natural havens and places of shelter must, of course, have been contem porary with the origins of navigation, and there are evidences of intercourse between Egypt and Crete in the pre-dynastic period of Egypt over 6,000 years ago. There are remains of very ancient harbour works in Crete, but, owing to earth movements most of them are under water. M. Gaston Jondet claims, in Les ports submerges de l'ancienne Ile de Pharos (Institut Egyptien, 1916), to have discovered at Alexandria vestiges of an ancient harbour in the Cretan manner, but the date and origin of these remains have been disputed (see also Sir A. Evans' The Palace of Minos, vol. i., 1921, and authorities there cited). These works are said to date from c. 2000 B.C. and to have been constructed on the seaward side of the island of Pharos, whereas the later harbour of Alexander (c. 332 B.C.) was placed between the island and the mainland. The Cretans did not confine their maritime adventure to the eastern Mediterranean, and Sir Arthur Evans is of opinion that there was trade between Crete and Britain in the early Bronze Age, between 1600 and 1200 B.C., centuries before the first coming of the Phoenicians to Britain. The Phoenicians built harbours at Sidon and Tyre in the 13th century B.C. The second city of Tyre was built on a small island off the coast. On either side of this island harbours were constructed protected by moles which appear to have been formed of rubble stone surmounted by masonry walls. These harbours and the city were of consider able extent and importance. In 332 B.C. Alexander the Great captured and destroyed the city, after building a causeway from the mainland to the island, and the port fell into decay. The causeway held up the drifting sands which accumulated on either side of it and the site of Tyre is now a peninsula.

It was after the capture of Tyre that Alexander founded the city of Alexandria and built the second harbour. He connected the island of Pharos with the mainland by a causeway, called the Heptastadion, which had two bridged openings in it. Later the famous lighthouse of the Pharos was built and moles were con structed affording additional protection to the east and west harbours on either side of the causeway (see E. Quellennec, Egyptian Harbours, XIV. Int. Congress of Nay. 1926).

Many other Mediterranean harbours, both natural and artificial, were of considerable commercial or military importance in Greek and Roman times. The natural harbours of Tarentum (Taranto) and Brundisium (Brindisi) are still in use. Ostia, once the port of Rome, is said by some classical writers to have been founded in the 7th century B.C., but the port of the empire was built by Claudius and extended by Trajan about loo A.D. (See Proc. Inst. C.E. Vol. IV., 1845). In Trajan's reign Civita Vecchia, 3o m. north of the Tiber mouth, was founded and Ostia was event ually abandoned as a port on account of the silting up of the approaches to it. The site of the harbour is now over 2 m. from the sea.

In mediaeval times the prosperity of such Mediterranean cities as Venice and Genoa led to the building of harbour works for the accommodation of their seaborne trade. Some of the early works at Genoa and on the Venetian lagoons remain to this day. Natural harbours suitable to the needs of the trade of the middle ages are more numerous in northern Europe than in the tideless Mediter ranean sea, and for many centuries these natural facilities, com bined in some cases with artificial works of the simplest character, sufficed for the shipping of the times.

One of the earliest protection works built at a seaport in Eng land was the Cobb at Lyme Regis dating from the 14th century. This was a pier or jetty constructed of rough boulders held in place between rows of oak piles. A pier occupying the same site still bears its name. Harbour works are said to have existed about 125o at Hartlepool and at Arbroath in Scotland c. Dover was a busy port in the time of Henry VIII., and a stone and timber breakwater was built there in his reign. Towards the end of the 16th century the first of the jetties at the entrance to the Yare at Yarmouth was constructed ; and in the 17th century protection piers were built at Whitby and Scarborough, portions of which still exist. It was not, however, until the second half of the 18th century when John Smeaton (q.v.) began his career, that the building of harbour works on any considerable scale was undertaken in England. Smeaton must be regarded as the founder in England of the science of harbour engineering. His work and that of his successors, Thomas Telford and John Rennie, permanently established British seaports in the forefront of progress in harbour construction.

On the other side of the channel, Havre, Dieppe, Rochelle and Dunkirk were among the earliest ports to embark on harbour construction; in Belidor's Architecture Hydraulique (Paris, 53) is a detailed account of the early harbour at Dunkirk as well as of other ancient port works.

In designing the works of a harbour one of the most important considerations is that of exposure. Such information as can be obtained from reliable charts must be supplemented by more detailed marine surveys and soundings, and the nature of the sea bed must be ascertained by borings and probings. Among the points to be noted are :—the geological and other physical char acteristics of the site; the slope of the sea bed; the depth of water seaward of the proposed site as well as over it ; the presence of any outlying reefs, rocks, shoals or islands of which advantage can be taken as affording protection, or as good foundations for sheltering works ; and the tidal phenomena, such as the vertical range. Investigation must be made of the nature and directions of the currents and tidal streams ; the effect of littoral drift ; the nature and extent of natural shelter; the directions of the prevail ing and of the strongest winds ; the line of maximum exposure, or the greatest fetch or reach of the sea in any unobstructed line of direction ; the probable maximum height of the waves due to the exposure ; and the direction from which the heaviest seas come. These and other considerations determine the character of the works to be constructed. In the case of harbours proposed to be made at the mouths of rivers or in estuaries, many other problems relating to river flow, bars, the maintenance of channels, etc., call for investigation.

There is a great diversity in the height of waves experienced in different positions on the same coastline. In some places shores lie open to the full force of the ocean waves while other parts of the same coast are protected by projecting headlands or islands, or by outlying reefs or sandbanks. Then again, inlets and enclosed arms of the sea, creeks, and river mouths, estuaries and land locked lagoons provide sites more or less sheltered from wind and waves according to the degree of natural protection afforded them. At the other extreme is the exposed open site where breakwaters are necessary to protect an anchorage harbour, and where secondary breakwaters or piers may be required to provide local and complete shelter for the inner works of the port.

In planning a harbour to be formed in an exposed situation, certain important points must be kept in view, e.g., (1) The en trance should be so placed as to afford ample sea room, free from rocks and shoals on a lee shore, for a vessel when on the point of entering or immediately after leaving the shelter of the outer and covering breakwater or breakwaters. (2) The alignment of the works should be such as to minimize the wheeling effect of waves around a breakwater head and the projection of seas across the entrance. (3) If possible the entrance should be so placed that one breakwater overlaps the other in such a way that some shelter from the direction of the heaviest seas is afforded to a ship when passing the harbour entrance. (4) The entrance should be planned so as to avoid strong currents sweeping across it. (5) Ample expending beaches or wave traps should be provided inside a harbour whose entrance is exposed, to allow the waves that pass the entrance to spend and break themselves. For this reason such a harbour surrounded with vertical walls, where there is not ample spending room, becomes a "boiling pot" of reflected waves; and in these circumstances sloping walls are preferable.

(6) The width of entrance, while being sufficient for the safe passage of ships, should be restricted as much as practicable; for upon the relation of the entrance width to the internal width and area of the harbour largely depends the reduction of range' 'Range, applied to waves, denotes the vertical rise and fall of sea waves particularly when they are propagated into a harbour; windlop describes the short wind waves generated in narrow waters as distinct from the ocean wave. The amplitude of the vertical motion of a ship due to range of waves is known as scend; tidal range is the vertical rise and fall of a tide; tidal rise the height of a tide at high-water above the chart datum which is usually the level of the lowest low-water.

in the latter. (7) The entrance width to a tidal harbour must not however be so restricted as to produce through the opening a current interfering with safe navigation. (8) The approaches to the entrance from seaward should not be obstructed by submerged dangers in or close to the recognized channel. If there be any such dangers in the vicinity of the harbour entrance they must be removed or, at least, suitably marked. (q) There should be suffi cient extra depth of water (over the nominal depth of the har bour) in the approaches and at and near the entrance to allow for the effect of range.

Waves.—The action of waves on solid structures is discussed under BREAKWATER (q.v.), and for theories concerning them and their phenomena see WAVES and TIDES ; the writings of the authorities mentioned in those articles should also be consulted. Here we will mention one matter closely connected with the selec tion of harbour sites.

The height of waves largely depends on what is termed the "fetch," that is, the distance from the weather shore, where their formation commences. According to Thomas Stevenson the following empirical formula is nearly correct for waves in the heaviest gales :—Height of wave from trough to crest in feet =1.5 Vd, where d is the maximum fetch in nautical miles. This formula presupposes unobstructed deep water, for waves of great height cannot reach any coast line or artificial obstruction unless there is an unbroken stretch of deep water for their propagation. Reefs and sandbanks, even though entirely sub merged, materially reduce the range of undulation; and a sudden change in the level of the sea bed, even in comparatively deep water, may produce a breaking wave. Moreover, it seldom happens in the heaviest gales that the wind is blowing for a sufficient length of time from the direction of and along the whole extent of the greatest fetch to bring about the generation of waves of the maximum possible height. The formula therefore gives too high a value when applied to a fetch exceeding about soo miles. The heights of waves are increased when they are propagated up funnel shaped or converging channels and are decreased when they pass into expanding channels.

Effect of the Angle of Incidence of Waves.—If the line of the outer face of a harbour work, such as a breakwater, is at right angles to the direction of the waves, the blow delivered by a wave against the solid structure will be at its maximum. When, however, seas strike the face in an oblique direction so as to be deflected towards the breakwater head and harbour entrance, the waves will sweep across the entrance, or wheel round the head, thus causing a turbulent cross sea at the point where vessels enter or leave the harbour. It is an advantage when the face of the breakwater can be aligned so that the heaviest seas assail it obliquely at such an angle that the waves are deflected away from the entrance and towards the inner or shore end of the structure. But in such cases the shore must be adequately pro tected, naturally or artificially, against scour.

It is a matter of common observation that the direction of waves is sometimes changed on passing a headland and that they will wheel round and enter a bay on the lee side of the head and break on a lee shore. A similar effect is often noticed in the case of islands and it frequently occurs at the head of breakwaters. The phenomenon is no doubt due to the frictional retardation of the inshore portion of the wave in shallow water. The deflec tion of waves during their passage up a wide channel between two shores is susceptible of similar explanation. Even if the wind is blowing and the waves are travelling up the channel in the direc tion of the centre line, the waves will be deflected and curve round so as to approach the shore on lines almost parallel with it.

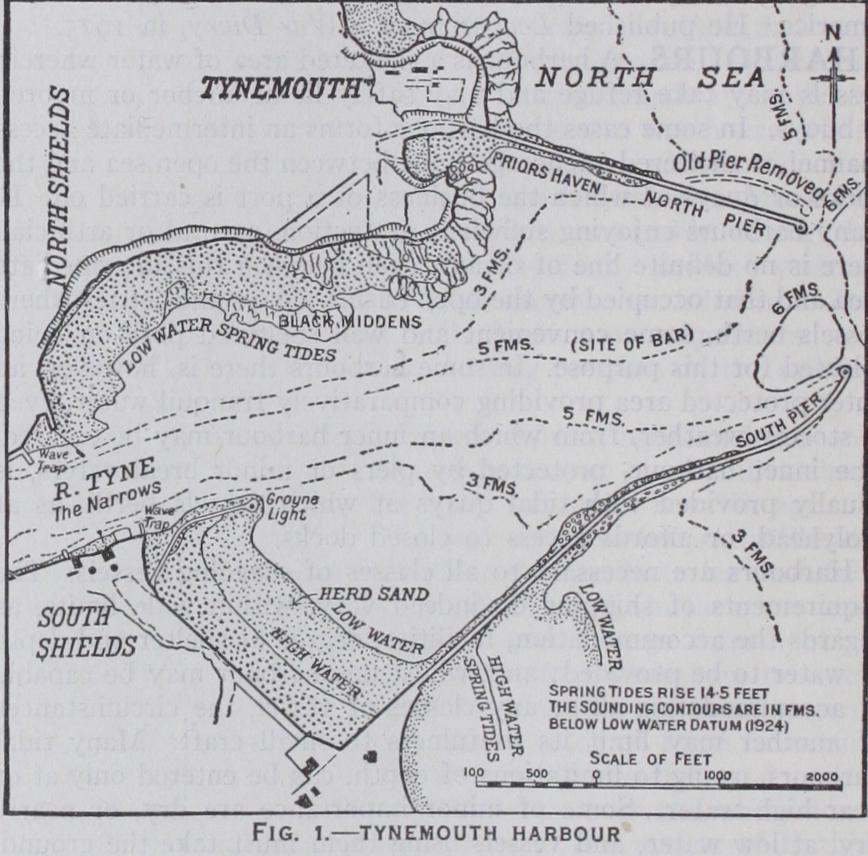

Spending Beaches and Range.—The best method of quickly reducing the height of waves entering a harbour is to secure their lateral expansion. This may be effected by widening the harbour immediately inside the entrance and providing for expending beaches; or by intercepting, by means of spurs, groynes or wave traps, the ends of the entering waves, thus admitting of endwise expansion after the interception has taken place; or by a corn bination of these means. (See Proc. Inst. C.E. vol. ccrx., 1921.) The first method is the more effective and is to be preferred for harbours whose entrances are exposed to heavy seas. The harbour at the Tyne entrance (fig. r) illustrates the combined effect of widening within the breakwater heads, expending beaches and wave traps. Waves 3o ft. in height have been observed just outside the entrance during a sustained gale from the north-east. The reduction of range between the pier heads and the Narrows at Sl_ields, a mile inshore, is over 9o%. The entrance between the outer pier heads is 1,18o f t., and the greatest width in the outer harbour is about 5,000 feet. The arrangement of breakwaters and spending beaches in the outer harbour at Sunderland, and in that at Ymuiden, is somewhat similar to the Tyne. Wave traps are frequently introduced in the planning of jetty harbours. (See below.)