Specific Heat at Low Temperatures

SPECIFIC HEAT AT LOW TEMPERATURES 47. The early experiments of Sir J. Dewar, Sir W. A. Tilden and others had shown that solids at low temperatures deviated from Dulong and Petit's law of the constancy of atomic heat in the same way as carbon, boron and silicon, at ordinary tempera tures, but they failed to show the full extent of the deviation, or to indicate a probable explanation. A. Einstein suggested (Ann. Phys., 1907) that the atom of a solid might be regarded as an electric resonator with three degrees of freedom possessing a particular frequency, independent of the temperature and cap able of responding to the same frequency of radiation. Adopting Planck's theory and radiation formula, he showed that the specific heat at constant volume should approach the limit 3R = 5.94 calories per gram-atom at high temperatures, as required by Dulong and Petit's law, but that the variation at low temperatures should be given by the expression (i8) where z =Ova' = c/X T, as in Planck's formula. The symbol v de notes the natural frequency of the atoms, and X the correspond ing wave-length in cm. such that the velocity of light. Taking H. F. Weber's observations on the variation of the specific heat of the diamond, extending from T= to 1,258° A, Einstein showed that they agreed qualitatively with this formula, if we could assume the diamond atoms to possess a single frequency corresponding to the wave-length I i microns. Taking the substances, CaFI, NaC1, KC1, and for which the optical frequencies in the infra-red were known, he showed that the frequencies agreed in order of magnitude with those required by his formula, but that the observed wave-lengths were somewhat shorter than those calculated from the specific heats. This could be attributed to the fact that most of the substances showed more than one frequency, and that the frequencies were not strictly monochromatic, as indicated by the width of the corresponding absorption bands. In any case there were other effects, such as work of expansion, included in the specific heats as ordinarily measured, and it might be doubted whether the optical frequencies corresponded exactly with the thermal vibrations of the atoms.

Experiments on Solids.

An important series of experimental measurements, extending down to the temperature of liquid hydro gen, was made by W. Nernst, F. A. Lindemann and their collab orators (Sitz. Akad., 1911), on a number of metals and other solids, including those for which the optical frequencies were known. They found, as already indicated, that Einstein's formula gave too low values for the specific heats at low temperatures, if the optical frequencies were assumed in calculating the value of f(z), and that much better agreement could be obtained by taking the mean of f(z) for the optical frequency, and a similar term, f(z/2) at half the optical frequency : 2)]j2 = 3Rf"(z) (19) The same function, f"(z), of z was assumed to apply to other sub stances, such as the metals, but the appropriate values of z were selected to fit the observations on the specific heats. Some sub stances, such as SiO., (in the forms of quartz and quartz-glass) and benzine, C,H,, which gave a different type of curve, were represented by formulae with two or three different values of z, each value of f"(z) being multiplied by a fractional coeffi cient representing the proportion in which the corresponding mole cule was supposed to be present. But such cases could not be regarded as a verification of the theory, because it would ob viously be possible to represent almost any type of variation in this way.Einstein objected that even the simplest of these formulae, namely (19), was too empirical to be satisfactory from a theoret ical standpoint; that a cubical crystal, such as KC1, or NaCl, could not have two different frequencies; and that there was no evidence in either case of an optical frequency with half the experimental value, since, according to Rubens, the crystals be came again transparent before this frequency was reached, and had a value of the refractive index which was nearly normal. He also indicated two other objections to the quantum theory on which Planck's formula was based. (1) According to the quan tum theory it did not follow, as required by the classical me chanics, that the oscillator with three degrees of freedom would have three times the energy of a linear oscillator. (2) It was very difficult to conceive the distribution of energy among the oscil lators at low temperatures required by the theory. Thus for the diamond at T= 73°A only one molecule in ioo millions would pos sess a single quantum of energy, all the rest would be absolutely quiescent. It was physically impossible to conceive such a distri bution of energy, which moreover would make the thermal con ductivity of the diamond at such temperatures entirely negligible, whereas, according to Eucken, it was nearly as great as that of copper at ordinary temperatures. For these reasons Einstein pre ferred to rely mainly on the expression for the energy of an electric oscillator in equilibrium with radiation as deduced from Maxwell's equations, and to regard Planck's formula for the dis tribution of energy in full radiation simply as representing the results of experiment.

Debye's Theory of Specific Heat of Solids.

The theory now most commonly accepted is that of P. Debye (Ann. Phys., 1912), who attributes the heat energy to mechanical or acoustic vibrations of the solid with all possible frequencies up to a cer tain limit According to a theorem attributed to the late Lord Rayleigh (Sound, i., 1877) the number of possible degrees of freedom of a system of N discontinuous mass-points will be 3N. According to another theorem by the same author (Phil. Mag., 1900) , the number of possible frequencies in a given volume of a continuous medium between the limits v and v+d v may be represented by where C' is a constant depending on the volume and the velocity of propagation. The total number of possible frequencies from o up to a limit is C'v,, If we equate this to 3N, we find Adopting Planck's expression for the energy of an electric oscillator with one degree of freedom as applying to each possible frequency of the N atoms in a gram-atom, we obtain the energy (RT/N)z/(e'-1) for each frequency. Multiplying this by the number of frequencies be tween v and v-}-d v , namely (9N/v, and integrating from o to we obtain the energy of a gram-atom at T, from which the specific heat at constant volume is obtained by differentiation with regard to T. Unfortunately the integral cannot be expressed in finite terms and is too complicated to reproduce here. It is evident, however, that it will be a function of z or or where T Thus the form of the curve representing the variation of the specific heat (which depends on a single parameter T,. or v„,) is the same for all substances on Debye's theory, if the temperature scale is altered for each in proportion to v,,,. This point has been very carefully tested by E. H. Griffiths and E. Griffiths (Phil. Trans., A, 191 4) for the metals Al, Ag, Cd, Cu, Fe, Na, Pb, Zn. Their results indicate qualitative agreement with the theory, but show characteristic differences, greatly exceeding the limit of experimental error, which may possibly be attributed to other effects not included in the simple theory. Thus the curve for Fe differs from that for Cu by nearly 20% between corresponding temperatures, which may be attributed to the magnetic properties of Fe. The curve for Na shows a rapid rise towards the melting point, reaching an excess of 25% above 3R, followed by a diminu tion of specific heat for the liquid, as in the case of water and mercury. Many simple compounds, such as NaCl, show curves of a very similar type to the metals, which has been used as an argument that the specific heat must be attributed entirely to the atoms, and that the free electrons supposed to exist in metals cannot make any appreciable contribution. Thus if there were two free electrons per atom, as required by some theories, the electrons alone would account for the whole specific heat according to the kinetic theory at ordinary temperatures; and it would be necessary to suppose that the number of free electrons diminished to zero at low temperatures, which would make it difficult to account for the enormous increase in electric conductivity of pure metals demonstrated by Kamerlingh Onnes in the neighbourhood of the absolute zero. There can be little doubt that the properties of any substance are intimately related to the natural frequencies of the molecules, but the form of the relation cannot be predicted with certainty; and the quantitative measurements are not yet sufficiently exact to distinguish between many possible hypotheses.

Specific Heat of a Gas.

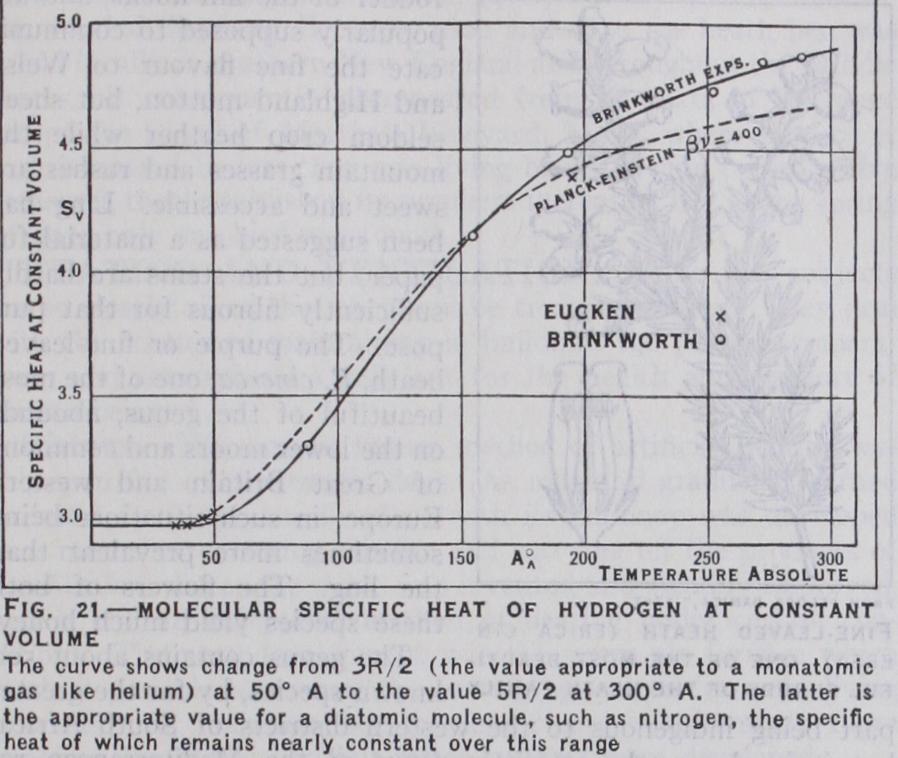

The experiments of A. Eucken (Sitz. Akad., Berlin, 1912) on the specific heat of hydrogen at low temperatures were very instructive in this connection. The gas was electrically heated at various temperatures in a thin steel vessel under considerable pressure at constant volume. The specific heat was found to diminish from nearly 5R/2 at ordinary temperatures to nearly 3R/2 at T= 60°, after which it remained practically constant down to T= 3 5 °. The experiments were undoubtedly of considerable difficulty, but there seems no reason to doubt their substantial accuracy.Eucken's results have recently been confirmed with remarkable precision by J. H. Brinkworth (Proc. Roy. Soc. (A) 1925) using an entirely independent method of experiment. He observed the cooling effect in adiabatic expansion with a compensated platinum thermometer at various temperatures between 2o° C and —183° C, and deduced the corresponding values of the ratio of the specific heats at constant pressure and at constant volume. The actual specific heats at any temperature could be deduced with certainty from these observations. This method is unaffected by the thermal capacity of the containing vessel, whereas in Eucken's method the thermal capacity of the vessel must be known with considerable accuracy. Brinkworth also showed that the heat-loss could be most satisfactorily eliminated by using vessels of different sizes. Assuming that the variation of the specific heat was due to the response of some particular frequency of the molecule to the same frequency in natural radiation at each temperature, he states that Callendar's radiation formula fits the observations better than Planck's but that satisfactory agreement cannot be obtained by assuming a single frequency. Reiche's calculations do not seem to improve the agreement.

It would appear that the specific heat of the most perfect gas may vary quite independently of the kinetic energy of its mole cules, and that the Boltzmann dumbbell model of a diatomic molecule, with five equal degrees of freedom, cannot longer be maintained. The form of the curve representing the variation of the specific heat between So° and 3oo°A aF shown in fig. 2I, is similar to that found for the diamond at low temperatures, and suggests that the variation is related to some natural frequency of the hydrogen molecule according to Einstein's theory but the exact nature of the relation remains at present obscure.