Hinduism

HINDUISM, a term generally employed to comprehend the social institutions, past and present, of the great majority of the people of India as well as their religious beliefs. Hinduism is also used in a narrower sense, as denoting more especially the modern phase of Indian social and religious institutions from the earlier centuries of the Christian era down to our own days.

Therefore, here are four main elements : religion, race, country, and social organization. They may not be separated. Each is bound up and is an integral factor in the life of the others. It is a living whole forged by the organic stresses of history and a long past, from diverse sources, from various materials, and it is still a living, vigorous whole.

Uniformity could not be expected as a feature of the religious experience of 232,000,000 people of different racial origins, of different history, of different environment, tradition, language, and social structure. Yet there is a true Hindu polity ; there are features common to North and South, to East and West. Much of it belongs obviously to the universal pattern for the age-long problems, whose presentations, at various times, in differing modes, constitute the stimulus to religious activity and are based ulti mately on certain definite universal experiences and facts. Man is born of woman, grows and withers like the grass. Whence and whither and why? The debate of fate, foreknowledge, freewill, follows inevitably certain lines, and the solutions to these prob lems conform to type because they are universal problems, where ever, as is markedly the case in India, thought has turned to the scrutiny and analysis of experience.

Main Doctrines.—The characteristic tenets of orthodox Brah manism (q.v.) consist in the conception of an absolute, all-em bracing spirit, the Brahma (neutr.), being the one and only real ity, itself unconditioned, and the original cause and ultimate goal of all individual souls (jiva, i.e., living things). As Sir Charles Eliot shows, there are at least two doctrines held by nearly all who call themselves Hindus. "One may be described as poly theistic pantheism . . . the second doctrine is commonly known as metempsychosis, the transmigration of souls or re-incarnation, the last-named being the most correct." Here most certainly are elements which Hinduism shares with and derives from lowlier cults. From these very elements and beliefs the social fabric draws its strength. They make for the stability of social struc ture. They validate morality. They have a survival value.

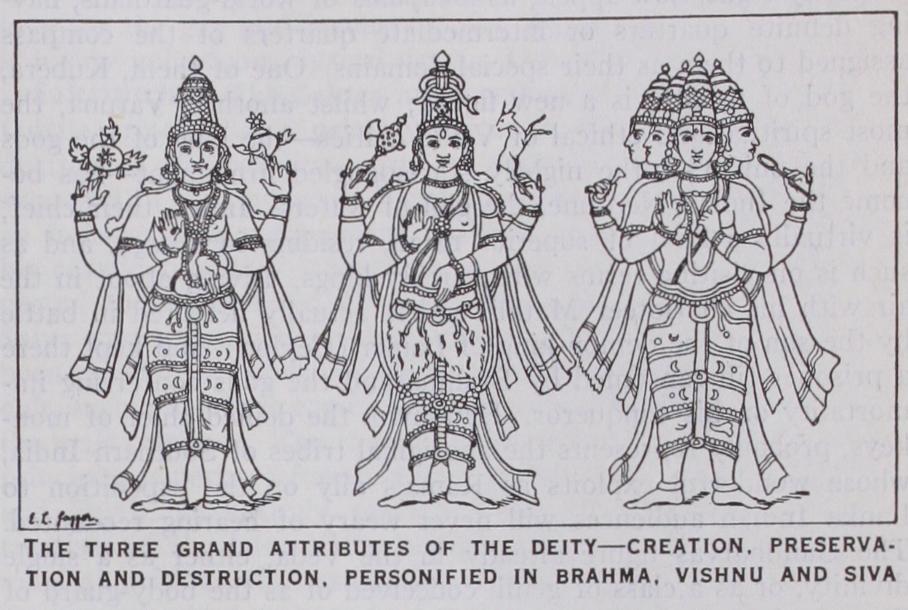

The ceaseless working of the Absolute Spirit as a creative, con servative, and destructive principle is represented by the divine personalities of Brahma (masc.), Vishnu, and Siva, forming the Trimurti or Triad. These latter two gods were in early days favourite objects of popular adoration. Sectarianism goes back beyond the formulation of the Brahmanical creed, right up to the Vedic age. Siva, so far from being merely the destroyer, is the representative of generative and reproductive power in nature. Brahma, having performed his legitimate part in the mundane evolution by his original creation of the universe, has retired into the background. The Trimurti has retained to this day at least its theoretical validity in orthodox Hinduism and has exercised influence in promoting feelings of toleration towards the claims of rival deities and a tendency towards identifying divine figures newly sprung into popular favour with one or other of the prin cipal deities, and thus helping to bring into vogue that notion of avatars, or periodical descents or incarnations of the deity, so prominent in later sectarian belief.

At all times orthodox Brahmanism has had to wink at, or ignore, all manner of gross superstitions and repulsive practices, along with the popular worship of countless hosts of godlings, demons, spirits, and ghosts, and mystic objects and symbols of every de scription. Fully four-fifths of the people of the Southern area, whilst nominally acknowledging the spiritual guidance of the Brahmans, worship nondescript local village deities (grama devata), with animal sacrifices, frequently involving the slaughter, under revolting circumstances, of thousands of victims. These local deities are nearly all of the female, not the male, sex. In the estimation of these people Siva and Vishnu may be more dignified beings, but the village deity is regarded as a more present help in trouble, and more intimately concerned with the happiness and prosperity of the villagers. This represents a religion, more or less modified in various parts of South India by Brahmanical influence. Many of the deities themselves are of quite recent origin, and it is easy to observe a deity in making even at the present day.

From the point of view of social organization (see CASTE) the cardinal principle which underlies the system of caste is the preservation of purity of descent, and purity of religious belief and ceremonial usage. Hindu polity is aristocratic, not egalitar ian. It recognizes, utilizes, and explains the inequalities of indi viduals and of groups of individuals. It is based on a sense of duty and of reciprocal obligation permeating the whole society from the king to the peasant. Dharma is duty. In the caste sys tem, with its hierarchical gradations, its complex relations, its jealous endogamy, its fissiparous nature, it expresses an exclusive ness which at first sight seems to create a rigid barrier, but its process of proselytization is by the absorption of whole commu nities, and that process is still active.

In the sphere of religious belief we find the whole scale of types represented from the lowest to the highest. In their theory of a triple manifestation of an impersonal deity, the Brahmanical theologians elaborated a doctrine which could only appeal to the sympathies of a comparatively limited portion of the people. The religious belief of the Aryan classes underwent changes in post Vedic times, due to aboriginal influences, and the later creeds offer many features in which one might suspect influences of that kind. The two epic poems, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, still show us in the main the personnel of the old pantheon ; but the gods have become anthropomorphized and almost purely mytho logical figures. A number of the chief gods, sometimes four, but generally eight, now appear as lokapalas or world-guardians, hav ing definite quarters or intermediate quarters of the compass assigned to them as their special domains. One of them, Kubera, the god of wealth, is a new figure ; whilst another, Varuna, the most spiritual and ethical of Vedic deities—the king of the gods and the universe; the nightly star-spangled firmament—has be come the Indian Neptune, the god of waters. Indra, their chief, is virtually a kind of superior rajah, residing in svarga, and as such is on visiting terms with earthly kings, driving about in the air with his charioteer Matali, and is actually defeated in battle by the son of the demon-king of Lanka (Ceylon), and kept there a prisoner till ransomed by Brahma and the gods conferring im mortality on his conqueror. Hanuman, the deified chief of mon keys, probably represents the aboriginal tribes of Southern India, whose wonderful exploits as Rama's ally on the expedition to Lanka Indian audiences will never weary of hearing recounted. The Gandharvas figure already in the Veda, either as a single divinity, or as a class of genii, conceived of as the body-guard of Soma and as connected with the moon. In the later Vedic times they are represented as being fond of and dangerous to women; the Apsaras, apparently originally water-nymphs, were closely associated with them. In the heroic age the Gandharvas have be come the heavenly minstrels plying their art at Indra's court, with the Apsaras as their wives or mistresses. Hence also the universal reverence paid to serpents (naga) since those early days. (See SERPENT CULTS.) In addition to such essentially mythological conceptions, we meet in the religious life of this period with an element of more serious aspect in the two gods, on one or other of whom the religious fervour of the large majority of Hindus has ever since concentrated itself, viz., Vishnu and Siva. Both these divine figures have out of Vedic conceptions, the genial Vishnu mainly out of a not very prominent solar deity of the same name; whilst the stern Siva, i.e., the kind or gracious one— doubtless a euphemistic name—has his prototype in the old fierce storm-god Rudra, the "Roarer," with certain additional features derived from other deities, especially Pushan, the guardian of flocks and be stower of prosperity, worked up therewith.

In the epic poems which took final shape in the early centuries before and after the Christian era, their popular character ap pears in full force ; whilst their cult is likewise attested by the coins and inscrip tions of the early centuries of our era.

The co-ordination of the two gods in the Trimurti does not exclude a certain rivalry between them ; but, on the contrary, a su preme position as the true embodiment of the Divine Spirit is claimed for each of them by their respective votaries, without, however, an honourable place being re fused to the rival deity, who is often repre sented as another form of the favoured god. The people's polytheistic instincts extended the pantheon by groups of new deities in connection with them. Two such new gods actually pass as the sons of Siva and his consort Parvati, viz., Skanda—also called Kumara (the youth), Kartti keya, or Subrahmanya (in the south)—the six-headed war-lord of the gods, and Ganesa, lord (or leader) of Siva's troupes of attendants, who is at the same time the elephant-headed, paunch bellied god of wisdom. A third, Kama (Kamadeva) or Kandarpa, the god of love, gets his popular epithet of Ananga, "the bodiless," from his having once, in frolicsome play, tried the power of his arrows upon Siva, whilst engaged in austere practices, when a single glance from the third (forehead) eye of the angry god reduced the mischievous urchin to ashes. For his chief attendant, the great god (Mahadeva, Mahesvara) has already with him the "holy" Nandi—identical in form as in name with Siva's sacred bull of later times, the symbol of the god's reproductive power. Thus we meet in the epics with the prominent feature of the worship of Siva and his consort all over India, viz., the feature represented by the linga, or phallic symbol. (See PHALLICISM.) As regards Vishnu, the epic poems, including the supplement to the Mahabharata, the Harivamsa, supply the framework of legendary matter on which the later Vaishnava creeds are based. The theory of Avataras makes the deity—also variously called Narayana, Purushottama, or Vasudeva—periodically assume some material form in order to rescue the world from some great calamity, the ten universally recognized "descents" being enu merated in the larger poem. The incarnation theory is peculiarly characteristic of Vaishnavism ; and the fact that the principal hero of the Ramayana (Rama), and one of the prominent war riors of the Mahabharata (Krishna) become in this way identi fied with the supreme god, and remain to this day the chief ob jects of the adoration of Vaishnava sectaries, naturally imparts to these creeds a human interest and sympathetic aspect which is wholly wanting in the worship of Siva.

Sectarianism.

During the early centuries of our era, whilst Buddhism, where countenanced by the political rulers, was still holding its own by the side of Brahmanism, sectarian belief in the Hindu gods made steady progress. The caste-system, by favouring unity of religious practice within its social groups, must naturally have contributed to the advance of sectarianism. Even greater was the support it received later on from the Pur anas, a class of poetical works of a partly legendary, partly discur sive, and controversial character, mainly composed in the interest of special deities, of which i8 principal (maha-purana) and as many secondary ones (upa-purana) are recognized, the oldest of which may go back to about the 4th century of our era. During this period, probably, the female element was first definitely ad mitted to a prominent place amongst the divine objects of sec tarian worship, in the shape of the wives of the principal gods viewed as their sakti, or female energy, theoretically identified with the Maya, or cosmic illusion, of the idealistic Vedanta, and the Prakriti, or plastic matter, of the materialistic Sankhya phi losophy, as the primary source of mundane things. The connubial relations of the deities may thus be considered "to typify the mystical union of the two eternal principles, spirit and matter, for the production and reproduction of the universe." But whilst this privilege of divine worship was claimed for the consorts of all the gods, it is principally to Siva's consort, in one or other of her numerous forms, that adoration on an extensive scale came to be offered by a special sect of votaries who therefore are known as the Saktas.

Sankara.

An attempt was made, about the latter part of the 8th century, by the distinguished Malabar theologian and phi losopher, Sankara Acharya, to bring about a uniform system of orthodox Hindu belief. The practical result of his labours was the foundation of a new sect, the Smartas, i.e., adherents of the smriti or tradition, which has a numerous following amongst southern Brahmans, and is usually classed as one of the Saiva sects, its members adopting the horizontal sectarial mark, pecu liar to Saivas, of a triple line, the tripundra, prepared from the ashes of burnt cow-dung and painted on the forehead.

Worship.

Since the time of Sankara, the gods Vishnu and Siva, or Hari and Hara as they are also commonly called—with their wives, especially that of the latter god—have shared be tween them the practical worship of the vast majority of Hindus. But, though the people have thus been divided between two dif ferent religious camps, sectarian animosity has upon the whole kept within reasonable limits. In fact, the respectable Hindu, whilst owning special allegiance to one of the two gods as his ishtd devata (favourite deity), will not withhold his tribute of adoration from the other gods of the pantheon. The high-caste Brahman will probably keep at his home a salagram stone, the favourite symbol of Vishnu, as well as the characteristic emblems of Siva and his consort, to both of which he will do reverence in the morning; and when he visits some holy place of pilgrimage he will not fail to pay his homage at both the Saiva and the Vaish nava shrines there. The same spirit of toleration shows itself in the celebration of the numerous religious festivals. Widely dif ferent, however, as is the character of the two leading gods are also the modes of worship practised by their votaries.

Siva.

The favourite god of the Brahmans has always been Siva. He is said to have first appeared in the beginning of the present age as Sveta, the White, for the purpose of benefiting the Brahmans, and he is invariably painted white. His worship is widely extended, es pecially in Southern India. Indeed, there is hardly a village in India which cannot boast of a shrine dedicated to Siva, and contain ing the emblem of his reproductive power; for almost the only form in which the "great god" is adored is the lingo, consist ing usually of an upright cylindrical block of marble or other stone, mostly resting on a circular perforated slab. The mystic na ture of these emblems seems, however, to be but little understood by the common people; and it requires a rather lively imag ination to trace any resemblance in them to the objects they are supposed to represent.The worship of Siva has never assumed a really popular character, especially in Northern India. The temple, which usually stands in the middle of a court, is as a rule a building of very moderate dimensions, consisting either of a single square cham ber, with a pyramidal structure, or of a chamber for the linga and a small vestibule.

Avatars.

From early times Vishnu proved to the lay mind a more attractive object of adoration on account of his genial character and the additional elements he has received through the theory of periodical "descents" (avatdra) or incarnations applied to him. At least one of his avatars is clearly based on the Vedic conception of the sun-god, viz., that of the dwarf who claims as much ground as he can cover by three steps, and then gains the whole universe by his three mighty strides. Of the ten or more avatars, only two have entered to any considerable extent into the religious worship of the people, viz., those of Rama (or Ramachandra) and Krishna, the favourite heroes of epic romance.It may not be without significance, from a racial point of view, that Vishnu, Rama, and Krishna have various darker shades of colour attributed to them, viz., blue, hyacinthine, and dark azure or dark brown respectively. The names of the two heroes mean ing simply "black" or "dark," the blue tint may originally have belonged to Vishnu, who is also called pitavasas, dressed in yel low garment, i.e., the colours of sky and sun combined.

By these two incarnations, especially that of Krishna, a new spirit was infused into the religious life of the people by the sentiment of fervent devotion to the deity, as expressed in cer tain portions of the epic poems, especially the Bhagavadgita, and in the Bhagavata-purana (as against the more orthodox Vaish nava works of this class such as the Vishnu-purana), and formu lated into a regular doctrine of faith in the Sandilya-sutra, and ultimately translated into practice by the Vaishnava reformers.

Eroticism and Krishna Worship.

The Vaishnava sects, in their adoration of Vishnu and his incarnations, Krishna and Ramachandra, usually associate with these gods their wives, as their saktis, or female energies, to enhance the emotional character of the rites of worship. In some of the later Vaishnava creeds, the favourite object of adoration is the juvenile Krishna, Govinda or Bala Gopala, "the cowherd lad," the foster son of the cow herd, Nanda of Gokula, taken up with his amorous sports with the Gopis or wives of the cowherds of Vrindavana (Brindaban, near Mathura on the Yamuna), especially his favourite mistress Radha or Radhika. This episode in the legendary life of Krishna bursts forth full-blown in the Harivansa, the Vishnu-purana, the Narada-Pancharatra, and the Bhagavata-purana, the tenth canto of which, dealing with the life of Krishna, has become, through vernacular versions, especially the Hindi Prem-sagar, or "ocean of love," a favourite romance all over India. Krishna's favour ite Radha makes her appearance in the Brahmavaivarta, in which Krishna's amours in Nanda's cow-station are dwelt upon in detail; whilst the poet Jayadeva, in the i 2th century, made her love for the gay and inconstant boy the theme of his beautiful, if highly voluptuous, lyrical drama, Gita-govinda.

Saktipu j a.

The Saktas are worshippers of the sakti, or the female principle as a primary factor in the creation and repro duction of the universe. And as each of the principal gods is supposed to have associated with him his own particular sakti, as an indispensable complement enabling him to perform properly his cosmic functions, adherents of this persuasion might be ex pected to be recruited from all sects. In connection with the Saiva system an independent cult of the female principle has been developed ; whilst in other sects, and in the ordinary Saiva cult, such worship is combined with, and subordinated to, that of the male principle. The theory of the god and his Sakti as cosmic principles is perhaps foreshadowed in the Vedic couple of Heaven and Earth, an entirely primitive concept. In the speculative treatises of the later Vedic period, and in the post-Vedic Brah manical writings, the assumption of the self-existent being divid ing himself into a male and a female half usually forms the start ing-point of cosmic evolution. In the later Saiva mythology this theory finds its artistic representation in Siva's androgynous form of Ardha-narisa, or "half-woman-lord," typifying the union of the male and female energies ; the male half in this form of the deity occupying the right-hand, and the female the left-hand side. In accordance with this type of productive energy, the Saktas divide themselves into two distinct groups, according to whether they attach the greater importance to the male or to the female principle, viz., the Dakshinacharis, or "right-hand-observers" (also called Dakshina-margis, or followers "of the right-hand path"), and the Vam.acharis, or "left-hand-observers" (or Varna margis, followers "of the left path") . Only in the numerous Tantras are Sakta topics fully and systematically developed.The principal seat of Sakta worship is the north-eastern part of India—Bengal, Assam, and Behar. The great majority of its adherents profess to follow the right-hand practice; and apart from the implied purport and the emblems of the cult, their mode of adoration does not seem to offer any very objectionable fea tures. And even amongst the adherents of the left-hand mode of worship, many of these are said to follow it, as a matter of family tradition, in a sober and temperate manner; whilst only an extreme section carry on the mystic and licentious rites taught in many of the Tantras.

The divine object of the adoration of the Saktas is Siva's wife —the Devi (goddess), Mahadevi (great goddess), or Jagan-mata (mother of the world)—in one or other of her numerous forms, benign or terrible. The forms in which she is worshipped in Bengal are of the latter category, viz., Durga, "the unapproach able," and Kali, "the black one," or, as some take it, the wife of Kala, "time," or death the great dissolver, viz., Siva. In honour of the former, the Durga-puja is celebrated during ten days at the time of the autumnal equinox, in commemoration of her victory over the buffalo-headed demon, Mahishasura ; when the image of the ten-armed goddess, holding a weapon in each hand, is worshipped for nine days, and cast into the water on the tenth day, called the Dasahara, whence the festival itself is commonly called Dasara in Western India. Kali, on the other hand, the most terrible of the goddess's forms, has a special service per formed to her, at the Kali-puja, during the darkest night of the succeeding month; when she is represented as a naked black woman, four-armed, wearing a garland of heads of giants slain by her, and a string of skulls round her neck, dancing on the breast of her husband (Mahakala), with gaping mouth and pro truding tongue, and when she has to be propitiated by the slaughter of goats, sheep, and buffaloes. On other occasions also Vamacharis commonly offer animal sacrifices, usually one or more kids; the head of the victim, which has to be severed by a single stroke, being always placed in front of the image of the goddess as a blood-offering (bali), with an earthen lamp fed with ghee burning above it, whilst the flesh is cooked and served to the guests attending the ceremony, except that of buffaloes, which is given to the low-caste musicians who perform during the service. Even some adherents of this class have, however, dis continued animal sacrifices, and use cer tain kinds of fruit, such as coconuts or pumpkins, instead. The use of wine, at one time very common on these occasions, is now restricted ; and only members of the extreme section adhere to the practice of the so-called five m's prescribed by some of the Tantras, viz., mamsa (flesh), matsya (fish), madya (wine), maitliuna (sexual union), and mudra (mystical fin ger signs).

Tantric theory has devised an elaborate system of female figures representing either special forms and personifications or attendants of the "great goddess." They are generally arranged in groups, the most important of which are the mahavidyas (great sciences), the eight (or nine) tuataras (mothers) or mahamataras (great mothers), consisting of the wives of the principal gods; the eight nayikas or mis tresses ; and different classes of sorceresses and ogresses, called yoginis, dakinis, and sakinis. A special feature of the Sakti cult is the use of obscure Vedic mantras, often changed so as to be quite meaningless and on that very account deemed the more efficacious for the acquisition of superhuman powers; as well as of mystic letters and syllables called bija (germ), of magic circles (chakra) and diagrams (yantra), and of amulets of various materials inscribed with formulae of fancied mysterious import.

Since by the universally accepted doctrine of karma (deed) or karmavipaka ("the maturing of deeds") man himself—either in his present, or some future, existence—enjoys the fruit of, or has to atone for, his former good and bad actions, Hindu thought has no precise belief in the remission of sin by divine grace or vicarious substitution. The "descents" or incarnations of the deity have for their object the deliverance of the world from some material calamity threatening to overwhelm it. Indeed, any man credited with exceptional merit or achievement, or even re markable for some strange incident connected with his life or death, might ultimately be looked upon as a veritable incarna tion of the deity, capable of influencing the destinies of man, and become an object of local adoration. The transmigration theory, which makes the spirit of the departed hover about for a time in quest of a new corporeal abode, lent itself to superstitious notions of this kind.

The worship of the Pitris ("fathers") or deceased ancestors, enters largely into the everyday life and family relations of the Hindus. (See ANCESTOR WORSHIP.) At stated intervals, to offer reverential homage and oblations of food to the forefathers up to the third degree is one of the most sacred duties the devout Hindu has to discharge. The periodical performance of the commemo rative rite of obsequies called Sraddha—i.e., an oblation "made in faith" (sraddha, Lat. credo)—is the duty and privilege of the eldest son of the deceased, or, failing him, of the nearest rela tive who thereby established his right as next-of-kin in respect of inheritance; and those other relatives who have the right to take part in the ceremony are called sapinda, i.e., sharing in the pindas (or balls of cooked rice, constituting along with libations of water the usual offering to the Manes). The first Sraddha takes place as soon as possible after the antyeshti ("final offer ing") or funeral ceremony proper, usually spread over ten days; being afterwards repeated once a month for a year, and subse quently at every anniversary and otherwise voluntarily on special occasions. Moreover, a simple libation of water should be offered to the fathers twice daily at the morning and evening devotion called sandhya ("twilight") . Anxious care was caused to the "fathers" by the possibility of the living head of the family being afflicted with failure of offspring, this dire prospect compelling them to use but sparingly their little store of provisions, in case the supply should shortly cease altogether. At the same time any irregularity in the performance of the obsequial rites might cause the fathers to haunt their old home and trouble the peace of their undutiful descendant, or even prematurely draw him after them to the Pitri-loka or world of the fathers. Terminating as it usual ly does with the feeding and feeing of a greater or less number of Brahmans and the feasting of members of the performers' own caste, the Sraddha, especially its first performance, is often a matter of very considerable expense ; and more than ordinary benefit to the deceased is supposed to accrue from it when it takes place at a spot of recognized sanctity, such as one of the great places of pilgrimage like Prayaga (Allahabad, where the three sacred rivers, Ganga, Yamuna, and Sarasvati, meet), Mathura, and especially Gaya and Kasi (Benares) . The pilgrim age to holy bathing-places is in itself an act of piety conferring religious merit. The number of such places is legion, and is con stantly increasing. The water of the Ganges, the Jumna, the Narbada, and the Kistna rivers, is supposed to be imbued with the essence of sanctity capable of cleansing the pious bather of all sin and moral taint. To follow the entire course of one of the sacred rivers from the mouth to the source on one side and back again on the other in the sun-wise (pradakshina) direction—that is, always keeping the stream on one's right-hand side—is held to be a highly meritorious undertaking which requires years to carry through. Water from these rivers, especially the Ganges, is sent and taken in bottles to all parts of India to be used on occasion as healing medicine or for sacramental purposes. Sick persons are frequently conveyed long distances to a sacred river to heal them of their maladies; and for a dying man to breathe his last at the side of the Ganges is devoutly believed to be the surest way of securing for him salvation and eternal bliss.

Conclusion.

Who can venture to say what the future of Hinduism is likely to be? Is the regeneration of India to be brought about by the modern theistic movements, such as the Brahma-samaj (q.v.) and Arya-samaj (q.v.) as so close and sym pathetic an observer of Hindu life and thought as Sir A. Lyall held? "The Hindu mind," he remarked, "is essentially specula tive and transcendental; it will never consent to be shut up in the prison of sensual experience, for it has grasped and holds firmly the central idea that all things are manifestations of some power outside phenomena. And the tendency of contemporary religious discussion in India, so far as it can be followed from a distance, is towards an ethical reform on the old foundations, towards searching for some method of reconciling their Vedic theology with the practices of religion taken as a rule of conduct and a system of moral government. One can already discern a movement in various quarters towards a recognition of imper sonal theism, and towards fixing the teaching of the philosophical schools upon some definitely authorized system of faith and morals, which may satisfy a rising ethical standard, and may thus permanently embody that tendency to substitute spiritual devotion for external forms and caste rules which is the character istic of the sects that have from time to time dissented from orthodox Brahmanism." Purified from within, Hinduism, in its highest expression, by which it, as any other religion has a right to be judged, with its great vitality, its power of adaptation, its philosophic tradition, its insistence on the development of the powers that are latent in man and are in jeopardy of being atro phied by modern dependence on machinery, may yet serve human ity by correcting the stress laid by other schools of thought upon the material to the neglect of the spiritual.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J.

Muir, Original Sanskrit Texts (2nd ed., 1873) ; Bibliography.-J. Muir, Original Sanskrit Texts (2nd ed., 1873) ; A. Barth, The Religions of India (1882) ; Monier Williams, Hinduism (1877), Modern India and the Indians (1878, 3rd ed., 1879), Reli gious Thought and Life in India (1883) ; J. C. Oman, Indian Life, Religious and Social (1879), The Mystics, Ascetics and Saints of Tndia (1903), The Brahmans, Theists and Muslims of India (1907) ; S. C. Bose, The Hindus as they are (2nd ed., Calcutta, 1883) ; W. J. Wilkins, Modern Hinduism (1887) ; Jogindra Nath Bhattacharya, Hindu Castes and Sects (Calcutta, 1896) ; E. W. Hopkins, The Religions of India (1896) ; J. Murray Mitchell, Hinduism Past and Present (2nd ed., 1897) ; Sir Alfred C. Lyall, Asiatic Studies (1899) ; Census of India, vol. i., pt. 1 (19o1) ; "Brahmanism," in Great Religions of the World (New York and London, 1902) ; "Hinduism" in Religious Systems of the World (London, 1904) ; J. Robson, Hinduism and Christianity (Edinburgh and London, 3rd ed., 1905) ; H. H. Risley and E. A. Gait, India; H. H. Risley, Ethnographical Appendices, vol. i. ; The Indian Empire, vol. i. (19o7).The census reports for 1911 and 1921 contain valuable data on the religious developments. The provincial reports are also full of matter. The publication of The Tribes and Castes of Bombay (1920), com pletes a series of most important books so far as the main part of continental India is concerned. The religions of the lower culture are dealt with in the Birhors by Sarat Chandra Roy (1925), and the monographs of the Assam and Burma ethnographical surveys. Sir Charles Eliot's Hinduism and Buddhism (1921) is a fine present ment of facts based on personal knowledge and a critical investi gation of the texts. Such works as The Crown of Hinduism by J. N. Farquhar (1913), The Chamars by G. W. Briggs (192o), and The Village Gods of Southern India (1921) by the Rt. Rev. Henry White head, D.D., may also be consulted.

See also articles: ARYA SAMAJ ; BRAHMANISM ; BRAHMA SAMAJ ; CASTE ; DADU PANTHIS ; KABIRPANTHIS ; MADHVAS ; MENDICANT MOVE MENT AND ORDERS (INDIAN) ; RAMANUJAS; RAMATS ; VAISHNAVITES; VALLABHACHARS.