Holland

HOLLAND, officially the kingdom of the Netherlands (Koningrijk der Nederlanden), a maritime country in the north west of Europe commonly known as Holland. This name, how ever, is that of the former countship which was largely the polit ical nucleus of the kingdom. North Holland and South Holland (q.v.) are but two of the II constituent provinces. Their geo graphical importance is partly indicated by their population, for they are the most densely populated political units.

Topography.

Holland is bounded eastward by Germany, south by Belgium, west and north by the North sea, and at the north-east corner by the Dollart. From slightly below Stevens weert to the south-west corner of Limburg the boundary line is formed by the river Maas or Meuse. At Maastricht, however, a portion lies beyond the left bank of the river, about 7,900 ft. from the outer glacis of the now dismantled fortress. The bound ary is defined "la ville de Maastricht . . . avec an rayon de ter ritoire de douze cents toises a partir du glacis exterieur de la place" (Item 2, Art. IV. of Treaty between Holland and Belgium, April 19, 1839). On the east a fairly continuous natural bound ary is represented by the line of marshy fens extending along the borders of Overyssel, Drenthe and Groningen. South of this the line is less definite, but the Maas in its great swing between Roer mond and Grave runs just west of the German frontier. The kingdom extends from 33' (Rottum island off Groningen) to 50` 46' (South Limburg), and from 3° 22' (near Sluis, Zeeland) to 7° 13' (East Groningen). The greatest length from north to south is thus about 190 m. ; its breadth varies considerably, the maximum from south-west to north-east entirely within its bor ders is about 16o miles. The area shows continual variation, di minishing by coastal erosion and increasing by diking and drain age operations. In 1926 the total land area was estimated at sq.m. or, inclusive of inland waters 13,210 sq.m. ; an esti mate in 1920 gave 15,760 sq.m. for land, inland waters, gulfs and bays. In no other country of Europe have the inhabitants been so instrumental in modifying the character of their home territory.

Coast and Relief.

The surface features and sea boundaries of the Netherlands are profoundly influenced by the fact that the country largely consists of the delta portions of two rivers, that of the Maas, commencing at Liege beyond southern Limburg, and that of the Rhine, commencing at Bonn; these delta areas overlap in northern Limburg and North Brabant, and from there northwards Zeeland can be interpreted as a portion of the same deltas plus deltaic material from the Schelde. The deltas are the direct result of the convergence of the waters of the three rivers into a tidal-node area where crest neutralizes trough and produces non-scouring conditions. North of the Zeeland archipelago the tidal set is more definitely north-east as the flow is assisted by prevalent winds and by the non-tidal water drift ; consequently the ebb set of the tide cannot return all material carried forward by the flow. In addition, Scandinavian inland ice swept south ward with its limit, in the Netherlands, roughly along the north west—south-east line Zaanvoort—Maartensdijk—Rhenen—Nij megen. Dependent on the former presence of this ice-sheet are the existing glacial ridges which occur in Drenthe, Overyssel, and particularly in Gelderland, and which have not only acted as watersheds and materially affected the drainage of to-day but have also had important effects on natural and cultivated vegetation and on the related activities of the Dutch people.The ridges, which run broadly north to south, are the result of tangential compression of the ice; they have a core of distorted and contorted fluviatile material of southern origin, and their lower slopes are locally covered by boulder clay, northern boul ders or fluvio-glacial debris. The last is sandy in character and frequently fills the hollows between the ridges. Five main ridges have been determined : Emmen to Groningen, Enschede to Oot marsum, Lochem to Havelte, Arnhem to Hattem, Rhenen to Bussum. West of the last ridge the glacial deposits sink below sea level, but have been proved in North Holland by borings. (See "Physiographic Regions of the Netherlands" by P. Tesch, Geographical Review [New York, 1923] pp. 507-517.) The sum mit height occurs on the Gelderland ridge north of Arnhem, where Imbosch mound reaches no metres (361 ft.). The non glaciated lands are low but show a slight increase of height south-eastward until south Limburg is reached; the increase there is rapid for that land, both geologically and orographically, be longs to the plateau bordering the north Ardennes. As a result of this it presents the Dutch with their only source of home coal. The summit height for all the Netherlands is in the extreme south east corner, where Holland, Germany and Belgium meet; here "Four Countries View" (Moresnet [Eupen-Malmedy] now be longing to Belgium was the fourth) reaches 322 metres (1,057 ft.). The amount of land exceeding i,000 ft. is microscopic and very little exceeds even Iso ft. More than 35% lies less than a metre above Amsterdam level. (Throughout the Netherlands, and also in adjacent German areas, the basis of the official measurement of altitudes is the Amsterdamsch Peil [A.P.] ; i.e., Amsterdam av erage high-water level of the Y at the time when it was open to the Zuider Zee.) Fully a quarter of the country in the west, fortunately fringed by the sand dunes, is actually below Amster dam Zero. Extreme depths reach 16-20 ft. below ; nevertheless the land is cultivated.

The coast forms a bold sweeping curve, concave to the sea in its south-western part and convex in its north-eastern section, broken in the south at the Zeeland—S. Holland archipelago, and again in the north, where such channels as the Marsdiep, Vlie, and Friesche Gat among the West Frisian islands give en trance to the Zuider Zee (see IMPOLDERING) and to that water land (wadden) which, extending along the Friesland-Groningen coast and beyond, is invaded by the sea at each flood. The charac teristic features of the coast are the chains of sand dunes nearly 200 m. in total length fringed by a broad, sandy beach shelving gradually seaward. In general, the dunes seldom exceed 3o-40 ft. though near Haarlem, i.e., in the centre of the unbroken strip, the High Blinkert is nearly 200 ft. above A.P. ; northwards where the winds have a wider sweep over the open sea the dunes are themselves wider, even exceeding 21 m. from west to east at Schoorl north-west of Alkmaar. The two main dune chains were formed in successive ages. The land bridge between Dover and Calais foundered and tidal currents swept eastward carrying sandy fragments of England and France which were built up into submarine shelly sandbanks between Calais and Texel ; the banks lengthened , and joined, though gaps remained opposite to the river mouths ; at low tide sand dunes were blown on to these oanks. New dunes grew on new banks seaward and cradled little flats of old beach between their successive ridges. This phase ended probably much prior to A.D. 300, as suggested by archaeo logical evidence and proved by other lines of study; e.g., the upper parts have had all lime removed by weathering but lower down there are abundant small fragments of common shells, while still below these is the basal sand-bed with whole valves of the same shells. (These remnants are sufficiently valuable to be worth extraction as a source of building lime in a land where the main calcareous deposits are as remote as the chalky hills of south Limburg.) The next and present period of dune-building was probably dependent on coast border changes near the Straits of Dover, or on local oscillations of the land and water levels, or on both. In any case, the upper portions of the basal sand-banks of the old est, i.e., eastern, of the Old Dunes, are now several feet below A.P. of to-day, and certain Roman structures have been discov ered below sea level. In some areas the Old Dunes have been entirely destroyed and the new dunes rest direct on new estuarine polder-clay, as in Zeeland-Flanders; along the greater part of the coasts of North Holland and South Holland both sets still exist with the newer on the seaward side though some new dune sands have been carried eastward and locally overlie the old dunes and the plains between them, and some have reached and even overwhelmed coastal patches on the Zuider Zee. This ten dency to an eastward drift is artificially arrested by the planting of reed grass. The westward growth of the line of dunes has within recent times changed seaports to inland towns, and a new settlement has arisen on the new coast, e.g., Egmond and Egmond aan Zee. (See NORTH HOLLAND.) There is thus a distinct west to east zoning in the Netherlands. The physical difference be tween adjacent strips has had important effects on the activities of the Dutch peoples. In the lee of the dunes are the dune pans, which are naturally marshy through the defective drain age of the clay-like soil, but the geest grounds where dune and pan meet can be planted with trees. The marshy pan is then gradually drained and cultivated, whilst the numerous springs at the dune base can be made to provide water for local use in the little settlement thus developed. Many old towns in North and South Holland, e.g., The Hague and Leyden have so originated. Modern developments have allowed the dune-base drinking water to be carried considerable distances—Amsterdam was so supplied in 1853, and other towns more recently. Beyond the geest lands are the low fens, usually still very marshy but gradually being reclaimed; still farther eastward, in North Holland, is the Zuider Zee, succeeded in turn by the eastern margin fenland, and finally by the elm and poplar patches, sandy heaths, high fens, and riverine meadow strips of the eastern frontier, which in every respect are much less typical of the accepted conception of Dutch scenery.

The entire drainage of the Netherlands is ultimately into the North sea. The principal rivers are the Rhine, the Maas (Meuse) and the Schelde (Scheldt), and each has its origin outside the country, whilst in the case of the Schelde only its two great sea channels are within the territory of the Netherlands. The Rhine in its course through this land is merely the parent stream, split ting up into Rhine and Waal above Nijmegen, Rhine and Yssel above Arnhem, Crooked Rhine and Lek (which takes most of the waters), near Wijk-by-Duurstede and at Utrecht into Old Rhine and Vecht, finally reaching the sea through the sluices at Katwijk. The Yssel and the Vecht reach the Zuider Zee; the other branches the North sea. The Maas, whose lower course is almost parallel to that of the Waal enters the Netherlands in the extreme south, forms the international boundary as far as Stevens weert, crosses Limburg to its north junction with North Brabant, and then closely follows the north boundary of North Brabant; from this province it receives its large lower tributaries, the Mark and the Dommel-Aa. Up to 1907 the main stream joined the Waal at Gorinchem and flowed to Dordrecht. From here Maas waters reached the sea by Old Maas and De Noord; the latter joining the Lek and reaching the sea as the New Maas. From Gorinchem the New Merwede (constructed in the second half of the 19th century) extends between dikes through the marshes of the Biesbosch to the Hollandsch Diep. These great slowly flowing rivers are very important waterways. In the Waal ordinary high tide water reaches beyond Gorinchem; in the Lek the limit is at Vianen ; in the Yssel, above the Katerveer, near Zwolle ; and in the Maas near Heusden. During spring tides, in each case the effect is felt considerably farther up-stream; e.g., in the Lek to Culemborg.

Into the Zuider Zee there also flow the Eem from Utrecht province ; the Vecht, with its tributaries Regge and Dinkel, from Overyssel ; and numerous shorter streams from Friesland. The total length of navigable channels is about 1,200 m., diminished during summer on account of shallows. The smaller streams, ex cept where they rise in the fens, often fertilize a strip of grass land in the midst of the barren sand, and are responsible for the existence of many villages along their banks. Artificial irriga tion is also practised by means of some of the smaller streams, especially in the east and south-east, and in the absence of streams a canal system is sometimes specially constructed for the same purpose. The low-lying areas at the confluences of the rivers, being readily laid under water, have been frequently chosen as sites for fortresses, but probably the greatest value of the rivers, apart from their direct use as waterways for transport, is their indirect use in this respect, viz., to act as permanent water supplies for the numerous canals. Practically every stream of any size in the Netherlands functions in this capacity.

Lakes.—Obviously lakes are particularly numerous though small; the largest have been drained. (See IMPOLDERING.) Many existing ones are merely marshes or flooded peat-pits, while several contain entrapped sea water. The typical "Lake District" is in Friesland. East of the Meppel-Leeuwarden line are several, e.g., Fluesen, Tjeuke Meer, Sloter Meer, Sneeker Meer, noted for abundance of fish or for their beauty of situation.

Dikes.

Some of the earliest inhabitants of the Netherlands of whom there is definite record were the Free Frisians, living in the far north of the country. They were not subdued by the Romans until A.D. 47, and prior to this had settled long enough to build extensive mounds (terpen or wierden) on the marshes exposed to inundation. These at first were merely high enough to protect the few rude huts on their summits from the normal rise of the tide, but in course of time the accumulated debris of settlement and drifted material increased their height and ex tent, so that they became safe refuges during mildly abnormal rises of tide. The experience thus gained, together with the pres ence over a considerable area of northern erratic boulders (see RELIEF) allowed the early inhabitants to build primitive dikes at the coast edge. The increased food resources of these newer sites led to the abandonment of many of the inland mounds, though many of the older towns and villages of Friesland and Groningen each still occupies a separate terp. The primitive dikes were steadily improved and much more ambitious schemes were launched, both here and in other parts of the Netherlands, par ticularly in the 12th and 13th centuries when the steady sinking of the land, or rise of the sea, created such serious problems. During this period the great sand-dune fringed fresh-water basin, the Flevo laces, of the Romans gradually increased in size, for the lower river channels which formerly carried the water sea wards became the waterways by which the sea entered the sinking basin; about A.D. 1300 Flevo locus had become a real southern sea bay, Almare of the North sea. Apparently this Zuider Zee inundation was more gradual than the catastrophic ones of A.D. 1277, when 3o villages in the lower Ems basin were destroyed on the formation of the Dollart, or the disastrous flood of 1421 when the Hollandsch Diep gave entrance to a sea which caused the destruction of 72 villages and more than 100,000 lives, and con verted a prosperous agricultural colony into a forest of reeds— Biesbosch. Again, a century later (1532) the fertile east of South Beveland, with 3,00o inhabitants, was submerged in a single flood and to-day it remains as Verdronken (Drowned) land.In view of the possibility of ever-recurrent even though minor inundations, e.g., in 1916, the Netherlanders have wisely de voted much money and applied the talents of skilled engineers to the construction of protective works. These of necessity must be of enormous size. Westkapelle dike, situated between West kapelle and Domburg, and the Hondsbossche Zeewering, from Kamperduin to near Petten, were built in the 15th century and were reconstructed and extended between 1860 and 1884 ; even such massive structures as these need constant inspection and maintenance, for although large blocks of basalt, as at Westka pelle, or of granite, as at the Helder, are used, yet gigantic wooden piles have been necessary to reach the more solid material below and to act as supports for the masonry. Many of the older piles had been riddled by the pile-worm (Teredo navalis), as its rav ages were not detected until 1731. At the present day electrical treatment is used for the destruction of the pests, and the engi neers also have available the more resistant ferroconcrete pile. A corps of engineers (De Waterstaat) is exclusively occupied on protection and reclamation works. In consequence, the detailed construction of the dike varies to meet the specific difficulties of different parts of the Netherlands. Probably Westkapelle is the finest of its type in the world; it is over 2 m. long, has a sea ward sloping face of 30o ft., and on its ridge (39 ft. broad) carries a road and service railway. Many others are of interest, as the Helder dike, about 5 m. long, 12 ft. wide (carrying a road) , with its end plunging 20o ft. into the sea at an angle of 40°. Such dikes as these are sea protection works; other dikes guide rivers and guard the adjacent lands.

Canals.

Parallel dikes either strengthen or replace the banks of rivers which are then deepened and kept permanently supplied with water. They then rank as canalized rivers, e.g., the New Merwede canal, from Amsterdam to the Rhine. In other cases the dikes bound newly cut excavations in preparation for entirely artificial canals. Typical of the largest is the North Holland canal (1819-1825) 46 m. long, 130 ft. broad and 20 ft. deep, with its level at Buickloot, 1 o ft. below the average level of the sea at half-tide. It runs from Amsterdam, where it is con trolled by the vast sea-gates (Willems Sluis), to the Helder; another is the North sea canal (1865-76) which, 15 m. long, 65-110 yd. wide and 22-26 ft. deep runs from Amsterdam almost due west to the North sea. As the surface of this canal is 20 in. below mean water level at Amsterdam it has been provided with gigantic locks and ponderous sea-gates apart from protective piers and dams. The total of navigable canal in the Netherlands is about 2,000 M.Dike-dams have also been thrown across rivers to control them, and several old towns owe their origin to such dams as Amster dam (1257) across the Amstel, Edam across the Y, and many others. Dams with lock-gates are used to close the sea exits not only of canals but of rivers also. Those of the Old Rhine near Katwijk aan Zee were built in 1807 to control the river. As far back as A.D. 839 a hurricane closed the river's mouth by sand accumulation : for nearly 1,000 years the pent-back waters spread out forming a huge swamp ; a canal was cut and three sets of locks were built with 2, 4 and 5 pairs of gates. These are closed during high tide (even during low tide with a strong on-shore wind) and are then successively opened to allow the accumulated water to escape, through the final control of the five pairs of seaward gates for 5-6 hr. at each ebb. The skill in dike and dam building manifests itself in the later erections of the great railway embankments such as those carrying the Flushing line over the island chain to the mainland, or the still more striking individ ual great bridge (1868-71) over the Hollandsch Diep which is 1$ m. wide.

Impoldering.

The presence of a dike is frequently sufficient in itself to cause an increase in the land available for occupa tion, as on the seaward face muds and sands are deposited by the sea. These become clad with vegetation and at certain states of the tide can be grazed ; the area consolidates and another seaward dike can then be erected. Nevertheless, the big reclamation schemes generally result from the total enclosure of a marshy area by encircling dikes. The isolated area occasionally improves by the mere shutting out of further water, but usually the entrapped water is removed by pumping it into outside drainage channels or canals. In particularly difficult cases this may necessitate the lifting of the water to successive levels by a series of individual pumps. The land thus reclaimed, polder, is normally extremely fertile. Although a great part of the Netherlands has now been impoldered the practice, on any considerable scale, dates back only to the period when heavy pumping became possible. The windmill was first so used in the 14th century and showed a high degree of reliability on the wide wind-swept lowlands, but to-day with water control needed over much greater areas with an in tricate system of canal and sluice, polder, dike and ditch, other pumping plants are being extensively used, such as steam and electrical. Fortunately, the more artistic ° windmill is likely to function for many years yet in this land deficient in coal and water power. Of the great and numerous impoldering schemes only a few can be selected.The most spectacular have been carried out in North Holland and South Holland. Near Alkmaar is the Schermer polder, the drainage of which demanded channels at four different levels. Immediately south of it are the Beemster, Wormer and Purmer polders centring on Purmerend. Here the Beemster (1608-12) produced some of the most valuable agricultural land in the Netherlands. Still larger is the famous Haarlemmermeerpolder. Up to 1840, Haarlemmer Meer was 18 m. long, 9 m. broad and 14 ft. deep, and had been produced by the ponding back of the Rhine in the 15th century and by the crumbling away of the banks of the Y. It began to imperil Amsterdam, Haarlem, Ley den and Utrecht, and its draining (1848-53) was largely a safety measure, nevertheless the reclaimed land, about 72 sq.m., has proved so valuable that the cost of the scheme (about f i,000,000) has already been repaid nearly threefold. Later the Y polder was reclaimed at the time of the construction of the North sea canal.

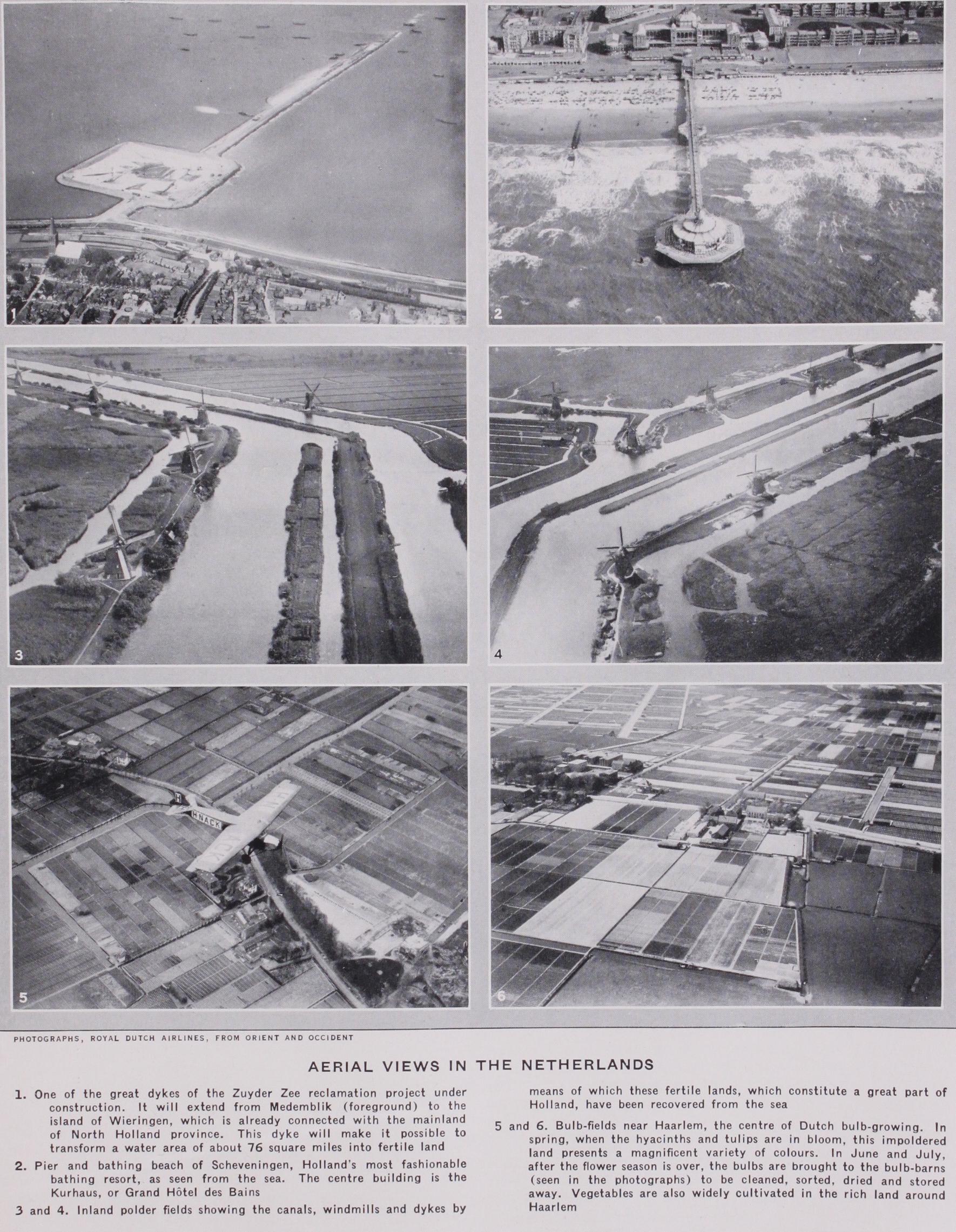

The largest impoldering scheme on record has now been com menced. In 1918, a law was passed for damming and draining of part of the Zuider Zee. The work commenced in 1924. The dam was completed in 1932. The first stage will add four polders of a total area of about 82o sq.m. (nearly the size of Limburg) to the country, at an outlay cost of about £51 millions. The main dike will extend from the island of Wieringen broadly north-east to the Friesland coast thus enclosing what will ultimately be a great fresh-water lake. The largest—the south-east polder (about 420 sq.m.) will extend from the coast, near Kampen, to south west of Amsterdam, near Muiden; the north-east polder (about 200 sq.m.) will follow a curving course through the island of Urk but leaving the Yssel channel unobstructed; the south-west polder (about 123 sq.m.) will run north-east from Marken and sweep back north-west to near Enkhuizen ; the north-west polder (about 76 sq.m.), running south-east from Wieringen, will prac tically fill the bay now existing north-west of Enkhuizen. Such giant schemes as this one and those already completed raise serious and somewhat technical questions, such as temporary storage of waters removed by pumping, the construction of perma nent reservoirs for the canal schemes, and, above all, the compli cated legal matters relating to drainage and water rights. For information on these, see the Gedenkboek uitgeven ter gelegenheid van het vij f tig jarig bestaan van het koninklijk Instituut van In genieurs ('s Gravenhage, 1898).

Climate.

Neither in latitude nor in altitude has the country a wide range, for from north to south it is less than 3°, and very little land exceeds 30o ft.; hence the climate is somewhat similar throughout. Nevertheless, as the winter isotherms do tend to run due north and south, and the summer isotherms to parallel the coast, then the east is more extreme than the west and the Netherlands, as a whole, have a colder winter than east England between the same latitudes. The recorded absolute minimum is nearly —6° F (38° frost). Utrecht may be considered as roughly central; here the average for the coldest month (January) is F, while farther east much of the traffic is ice-borne during winter. The average for the hottest month (July) at Utrecht is 62.6° F. The south-west winds prevail for about nine months annually raising the winter temperatures, but are replaced by the April—June north-west winds, which produce a cooler summer. As a consequence of the wind direction the west part of the coun try, particularly along the dunes, is wetter than the east. The annual total rainfall average for the whole country is not high, probably less than 28 in. ; the figures for Utrecht are 27.5 in. annually, with July—Sept. (9.2 in.) as the three wettest months, and Feb.—April (4.7 in.) as the three driest. This early spring minimum results in actual shortage in the east during dry years and some of the canals are then used as irrigation channels. The mean annual number of "rain-days" slightly exceeds 200, but probably more important is the constant high degree of humidity (exceeding 8o%) consequent on the large amount of standing water ; marsh mists and sea fogs are frequent, and seem to have harmful effects in Friesland and Zeeland, where the med ical statistics for pulmonary diseases suggest rather disquieting conditions.

Fauna.

In densely populated areas with no extensive forests, the fauna seldom present unusual varieties. In the Netherlands the otter, marten and badger are found, though rarely, but the weasel, ermine and pole-cat are more common. In the 18th century wolves roamed the country in large numbers; now they are un known. Wild roebuck and deer are found in the drier wooded regions to the east of the country; here foxes are still plentiful. In the dunes and other sandy stretches the hare and rabbit occur in large numbers. Birds are unusually well represented; about 240 different kinds are regular inhabitants, although nearly 200 of these are migratory. The woodcock, partridge, hawk, water-ousel, mag pie, jay, raven, various kinds of owls, pigeon, wren, lark, titmouse and others breed in the Netherlands while birds of passage include the buzzard, kite, quail, wild fowl of various kinds, thrush, wagtail, linnet, finch and nightingale. The beautiful plumaged heron haunts the mud-flats and the protected house-stork with its large clumsy nest is a typical Dutch feature. Fish are important ; eels are trapped and smoked as food reserves; flat-fish are a source of wealth in the Zuider Zee, herrings are netted in the North sea and shellfish, chiefly oysters, are dredged in Zeeland.

Flora.

The four physiographical divisions, namely, the heath lands, pasture-lands, dunes and coasts are characterized by dif ferent flora. Heath and ling cover the waste sandy regions in the east of the country. In the more damp and marshy meadow lands the bottom is covered with marsh trefoil, carex, smooth equisetum, and rush, while common water-lilies, water-soldier, reed-mace, flag and bur-reed are seen in the ditches and pools. Dune flora types are usually stunted and meagre as compared with the same forms elsewhere. The most important plant, sown an nually to bind the loose sand together, is the Dutch helm, or smooth reed-grass (Arundo arenaria). It is much used for mat making in Drenthe and Overyssel. The dewberry bramble and the buckthorn also help to bind the sand together. Furze and common juniper, used as a flavouring in the "Hollands" gin of Schiedam, occur both on the dunes and on the eastern heaths. The most gen eral of the other dune plants are thyme, small white dune-rose, wall pepper, fever-wort, common asparagus, sheep's fescue grass, Solomon-seal and the marsh orchis. Certain plants are specially cultivated to assist in consolidating the mud flats and in enlarging the littoral deposits; of these the sea-aster flourishes in the northern Wadden (see CoAsT) giving place nearer shore to sand spurry and to floating meadow grass, which afford pasture for cat tle and sheep. Along the coast of Overyssel and in the Biesbosch lake club-rush is extensively planted for the basketry and other plaiting industries. In the northern half of the Zuider Zee the common sea-wrack is gathered for trade purposes during the sum mer months. Except for the pollarded willows found along the rivers on the clay lands, nearly all the natural wood is confined to the sandy gravel soils; here copses of elm, poplar, birch and alder are common. • Colonies.—The colonial possessions of the Netherlands include territories in the East Indies and the West Indies. The former, the Dutch East Indies, dating back to 1602, consists of a large number of low-latitude Pacific islands of an approximate total area of 735,000 sq.m. with a population of over 51 millions (1925), in which oriental natives vastly predominate; for example in 1926 the remarkably densely populated islands of Java and Madura (717 persons per sq.m.) had less than 170,000 Europeans out of a total population of 37,000,00o. The Dutch West Indies, dating back to 1667, consist of Surinam and Curacao with the dependencies of the latter; the total area is less than 55,000 sq.m., and the population in 1926 was almost exactly 200,000, of whom very few were Europeans.

Population.

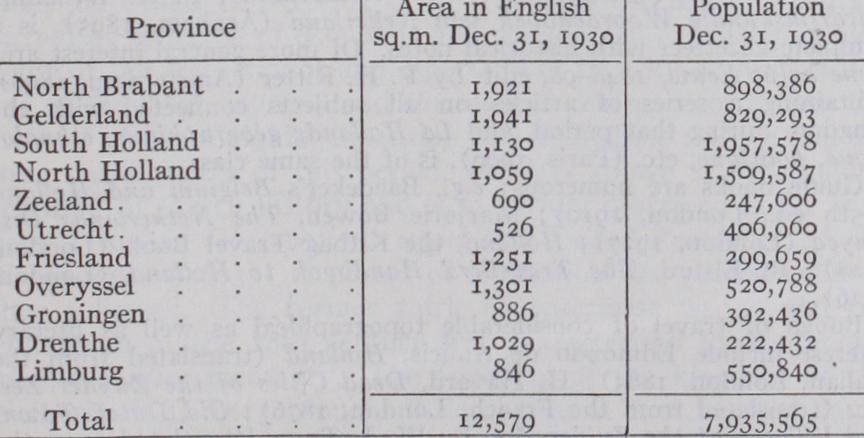

The following shows the area and population of the Netherlands according to the communal population lists of Dec. 31, 1926.

The last census was taken in 1930—population 7,935,565 of whom were males showing less disparity between the sexes than is the case in other non-belligerent European countries. Other census returns indicate a steady and considerable popula tion increase. Approximate figures (to nearest one-eighth mil lion) were 1829, 21; 3; 1869, 3$; 41; 5$.

According to the census of 193o South Holland and North Hol land, with the high density of 1836 and 1,426 persons to the sq.m. respectively, are the most populous provinces; at the other ex treme are Drenthe with 216 and Friesland with 32o. At the be ginning of the loth century the order was the same. The average density for the whole country during this period has increased from 404 to 632 per sq. mile. The most striking total increases in the provinces are South Holland from 981 and North Holland from 905, but the largest percentage increase is Limburg with 90%. No province has diminished in density, but Zeeland, with 313 in 1900 and 359 in 1930, has shown the least change. The townward movement continues and the percentage of rural popu lation has fallen from 62.89 in 1889 through 56.27 in 54.37 in 192o to 51.2% in 1930. The excess of births over deaths has shown a steady decrease in the period 1923-30 (inclusive) but has averaged about 109,000 per annum. Emigration (mostly to North America) has been slight in the same seven years, averaging less than 4,000 per annum. The largest towns in 193o were Amster dam 757,386, Rotterdam 586,952, The Hague 437,675, Utrecht 154,882. Next in order over 50,000 were Haarlem, Groningen, Eindhoven, Nijmegen, Tilburg, Arnhem, Leyden, Maestricht, Apeldoorn, Hilversum, Dordrecht, Schiedam, Enschede, and Delft. In 1930, 46 towns had populations above 20,000.

Constitution and Government.

The first Constitution of the Netherlands dates to 1814 (see HISTORY), but has been revised at intervals; most recently in 1917 and 1922. The important re visions of 1815 and 1840 were consequent on the addition and the secession, respectively, of the Belgian provinces. The Nether lands form a constitutional and hereditary monarchy, succession being in both the male and female line according to primo geniture, though female succession takes place only in default of male heirs. The widely-interpreted executive power of the State is vested exclusively in the sovereign, whose age of majority is 18 years. The whole legislative power rests conjointly in the king and the States-General (parliament). The upper chamber of parliament, 5o members, is elected for six years by the Provincial States (see LOCAL GOVERNMENT, below) and half retire, by rota tion, at the end of three years. Each member not resident in The Hague, where the States-General meets, is allowed an expense grant of 10 guilders per day during the parliamentary session, but unless holding special office is otherwise unpaid. The sovereign's executive power is in part exercised by responsible ministers, who hold office at the pleasure of the sovereign. There are at present ten ministers controlling finance, foreign affairs, interior with agriculture, justice, colonies, war, public works (Waterstaat), marine, labour and instruction. The posts are salaried (16,00o guilders per annum), though an additional special grant, for representation, is made to the minister of foreign affairs. The lower chamber, which shares with the Government alone the privi lege of initiating new bills and proposing amendments, consists of 10o deputies who are elected directly for four years and retire en bloc. Each deputy receives an annual salary of s,000 guilders together with travelling expenses. Certain legislative and many executive matters are normally referred to a State council (Raad van Staat) consisting of 14 members appointed by the sovereign, who is also president of the council.Since Dec. 12, 1917, suffrage has been universal for all Dutch subjects of 25 years of age, though reasonable exclusions are made in the case of certain civil disabilities. Elections are on a basis of proportional representation and the sovereign has the power to dissolve either or both chambers, subject to new elec tions within 4o days and a new assembly within two months.

Local Government.

Each of the 11 provinces has a local representative body—the "Provincial States," composed of mem bers, not less than 25 years of age. All members are elected for four years by the inhabitants of the province who make use of a franchise system resembling that employed for selection of the lower chamber deputies. The Provincial States, which vary in size according to the number of inhabitants in the province, elect the members of the upper chamber of the States-General, collect local taxes and legislate on welfare schemes of special and peculiar importance to the province though all such financial and legislative matters have to receive crown sanction. The Pro vincial States meet twice annually but their executive work and the daily administration of provincial affairs is in charge of 64 of their number (six from each province excepting Drenthe, which supplies four members) . These, who constitute a permanent paid committee are termed the Deputed States. The Provincial States, as is the case with the Deputed States, are presided over by a salaried crown commissioner who, in the latter body, is the chief magistrate of the province. This becomes necessary because an important duty of the deputed States is the administration of the common law in the several provinces. Each of the com munes (1,o81 in 192 7) elects a local council varying in size from seven to 45 members. Each member must be 23 years of age and a resident in the commune; the electoral system resembles that in use for the higher bodies. The communal council raises taxes, administers a municipal budget and makes and enforces communal by-laws subject to the approbation of the Deputed States. The crown appoints a mayor, with a six years' term of office, to preside over the communal council which vests its executive power in a college consisting of the mayor and two to six aldermen (wethouders). The mayor, as a direct crown repre sentative, not only controls the municipal police but also super vises the work of the communal council and may suspend their resolutions for 3o days, though this extreme step must be reported to the Deputed States for more authoritative deliberation.

Justice.

Trial by jury is unknown in the Netherlands. Minor offences are tried by one judge in the cantonal court, of which exist. More serious cases reach one of the 23 district tri bunals with one or three judges in attendance. Beyond these are five courts of appeal, widely spaced over the country, which in turn are subject to the high court (hooge road) of the Nether lands, which sits at The Hague with five judges in deliberation. The high court is not only the final court of appeal on points of law but is also the tribunal for the members of the States-General and for all high Government officials, including judges ; the last are normally appointed for life by the sovereign. Recently, as a part of the reform movement in treatment of young criminals, juvenile courts have been called into existence. At these courts children's civil cases are tried by a specially selected judge, who also administers justice in relation to certain criminal acts of persons below the age of 18 years. During the three years 1924-26 there were on an annual average 7,700 males and 32o females in the 28 prisons; 16,300 males and 85o females in the 27 houses of detention; and 2,900 males and 33 females in the five State-work establishments. The State reformatories are of two types : (a) the more severe reformatory; and (b) the disciplinary school. In the latter, children are admitted by request of parents or guar dians. The former during the 1924-26 period had an annual attendance of 90o boys and ioo girls and the latter 43o boys and 85 girls—the last number showing a steady yearly increase.

Charitable Institutions.

The guiding principle, based on the law of 1854, with regard to pauperism in the Netherlands has been that the State takes charge only when private charity fails, and although recent reorganization has tended to reduce the number and somewhat limit the activities of private charities they still occupy a more prominent position in the life of the community than is the case in many countries. The most impor tant of such private institutions aim rather at the utilization of labour in new areas coupled with instruction courses designed to render labour available for new activities. Special mention should be made of the agricultural colonies controlled by the Society of Charity. (See DRENTHE.) Nevertheless, in 1925, the State dis bursed over 55 million guilders in normal poor relief ; a figure which was largely increased by unemployed relief. In 1916 a Government scheme of unemployment insurance was initiated.A feature of Dutch culture is the large number of prosperous institutions for the encouragement of science and the fine the majority of these institutions were founded during the cen tury (1750-185o). In addition to the strictly national societies, numerous municipal institutions and associations cater for more than local interests. From a long list of such valuable culture aids perhaps special reference can be made to the institute of Language, Geography and Ethnology of the Dutch Indies (founded 185i at The Hague) which has undoubtedly contributed materially to sympathetic understanding and the successful administration of Holland's distant colonies.

Religion.

Although the royal family and a large number of the inhabitants belong to the Reformed Church yet entire liberty of religious conscience is granted to citizens of the Netherlands— a continuation of that feature of religious liberty first stated in the revised Constitution of 1848. Financially, the practice is il lustrated by the State budget (1928) when the following approxi mate allowances were made. Protestant churches 1,411,00o guil ders; Roman Catholics 579,000; Jews 15,000; Jansenists 12,000. The 1920 census analysis showed the following total adherents throughout the country. Dutch Reformed Church 2,826,633; other Protestants 832,000; Roman Catholics 2,444,583; Jews 115,223; Jansenists 10,461; unknown i,o i o thus leaving the sig nificantly large total of 635,240 (nearly io%) of other creeds or of no creed. The government of the Reformed church is Pres byterian and its present organization dates from 1852. The con trolling body is the main "synod" of deputies meeting annually. The provincial synods at the end of 1927 numbered ten, sub divided into 44 classes and a still larger number of circles drawn from 1,348 parishes in the care of about 1,650 ministers. (These figures include Walloon, English, Presbyterian and Scotch churches whose church government differs but little from that of the much larger Dutch Reformed Church.) Each congregation is governed by a "church council," and the scheme of supervision of ecclesiastical administration, though complicated, covers all stages from the main synod to the individual "church council"; financial control is much more individual. In 1853 the Roman Catholic Church in the Netherlands, previously merely a mission in the hands of papal legates and vicars, was elevated to an independent ecclesiastical province. (See UTRECHT PROVINCE.) In 1927 there were one archbishop (of Utrecht), four bishops and 1,295 parishes. The Roman Catholic element is most marked in the southern provinces of Limburg and North Brabant though the bishoprics have a much wider extension. The Jewish popu lation of the Netherlands is largely consequent on the influence of Portuguese Jews at the end of the 16th and of German Jews in the beginning of the 17th century. In 187o they were reorgan ized under a central authority, The Netherlands Israelite church. In 1927 the Jews had 146 communities in the country. (For further details of the above and other religious bodies see The C'iurcli in the Netherlands, by P. H. Ditchfield, London, BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A general official handbook appeared in 1922, HandBibliography.-A general official handbook appeared in 1922, Hand- boek voor de Kennis van Nederland en Kolonien (The Hague) . Rather technical works include H. Blink, Nederland en zijne Bewoners (3 vols., Amsterdam, 1888-92), containing a copious bibliography ; Opkomst van Nederland als Economische-Geographisch Gebied van de Oudste Tijden tot Heden (Amsterdam, 1925) ; P. J. Blok, Geschiedenis van het Nederlandsche Volk (Eng. trans. parts 1-4, London, 1898-1912) ; A. A. Beekman, De Strijd om het Bestaan (Zutphen, 1887), a manual on the characteristic hydrography of the Netherlands ; P. H. Witkamp, Aardrijkskundig Woordenboek van Nederland (Arnhem, 1895), is a complete gazetteer with historical notes. Of more general interest are: Eene halve Eeuw, 1848-98, edit. by P. H. Ritter (Amsterdam, 18q8), containing a series of articles on all subjects connected with the kingdom during that period, and La Hollande geographique, ethnolo gique, politiqi,se, etc. (Paris, 190o), is of the same class.Guide books are numerous ; e.g., Baedeker's Belgium and Holland (15th ed., London, 191o) ; Marjorie Bowen, The Netherlands Dis played (London, 1927) ; Holland, the Kitbag Travel Book (London, 1928) ; R. Elston, The Travellers' Handbook to Holland (London, 1926).

Books of travel of considerable topographical as well as literary interest include Edmondo de Amicis, Holland (translated from the Italian, London, 1883) ; H. Havard, Dead Cities of the Zuyder Zee, etc. (translated from the French, London, 1876) ; Old Dutch Towns and Villages of the Zuider Zee, by W. J. Tuyn (translated from the Dutch, London, 1901) ; E. V. Lucas, A Wanderer in Holland (London, 1923) ; C. G. Harper, On the Road in Holland (London, 1922) ; P. M. Hough, Dutch Life in Town and Country (London, Igo') ; D. S. Meldrum, Holland and the Hollanders (London, 1899) ; Friesland Meres and through the Netherlands, by H. M. Doughty (London, 1887) ; Hollande et hollandais by H. Durand (Paris, 1893) . Works of historical and antiquarian interest are Merkwaardige Kasteelen in Nederland, by J. van Lennep and W. J. Hofdyk (Leiden, 1881-84) ; Noord-Hollandsche Oudheden, by G. van Arkel and A. W. Weisman, published by the Royal Antiquarian Society (Amsterdam, 1891) and Oud Holland, edit. by A. D. de Vries and N. de Roever (Amster dam, 1883-86) . Natural history is covered by various periodical publications of the Royal Zoological Society "Natura Artis Magistra," at Amsterdam, and the Natuurlijke Historie van Nederland (Haarlem, 1856-63). Military and naval defence may be studied in De vesting Holland, by A. L. W. Seijffardt (Utrecht, 1887), and the Handbook of the Dutch Army, by Major W. L. White, R.A. (London, 1896). For bibliographical references to statistics and trade see article on NETHERLANDS; Economics and Financial conditions. (W. E. Wu.) Geology.—Except in Limburg, where, in the neighbourhood of Maastricht, the upper layers of the chalk are exposed and fol lowed by Oligocene and Miocene beds, the whole of Holland is covered by recent deposits of considerable thickness, beneath which deep borings have revealed the existence of Pliocene beds similar to the "Crags" of East Anglia. They are divided into the Diestien, corresponding in part with the English Coralline Crag, the Scaldisien and Poederlien corresponding with the Walton Crag, and the Amstelien corre sponding with the Red Crag of Suffolk. In the south of Holland the total thickness of the Plio cene series is only about 200 ft., and they are covered by about ft. of Quaternary deposits; but towards the north the beds sink down and at the same time increase considerably in thickness. The Pliocene beds were laid down in a broad bay which covered the east of England and nearly the whole of the Netherlands, and was open to the North Sea. There is evidence that the sea gradu ally retreated northwards during the deposition of these beds, until at length the Rhine flowed over to England and entered the sea north of Cromer. The appearance of northern shells in the upper divisions of the Pliocene series indicates the approach of the Glacial period, and glacial drift containing Scandinavian boulders now covers much of the country east of the Zuider Zee. The more modern deposits of Holland consist of alluvium, wind-blown sands and peat. Of late years an intensive boring campaign has revealed many interesting details of ancient rock-structures buried at great depths, both coal and salt deposits having been reached in Lim burg and at various points near the German frontier. For details see Jaarverslag der Rijksopsporing van Delfstoffen (annual re ports published by the Government). (G. E., R. H. RA.)